Sean Gibson has gazed at the grainy photos and heard all the stories about his great-grandfather, Negro Leagues star Josh Gibson. Yet, “Big Josh,” as he’s known in the Gibson family, died more than 20 years before Sean Gibson was born, and the still-life images and time-tinged memories of ball games played nearly a century ago don’t paint a complete picture of the broad-shouldered catcher who clubbed tape-measure home runs.

In baseball, statistics are the paramount measure of greatness. Long before cable television and online streaming made it possible to watch any game with a single click, poring over the box scores in the newspaper was the only way for baby boomers to compare their favorite players from different teams. Heated debates about who deserved to be enshrined in the Hall of Fame often were resolved by the numbers of the backs of baseball cards. In the spring of 1980, a handful of baseball junkies in New York drafted imaginary teams and “played” a season by calculating stats based on the players’ actual performance. That first rotisserie baseball league spawned a multibillion-dollar fantasy sports industry.

And so, when Major League Baseball announced in late May that it finally would absorb Negro League data into its official record, Sean Gibson took a fresh look at his great-grandfather’s stats.

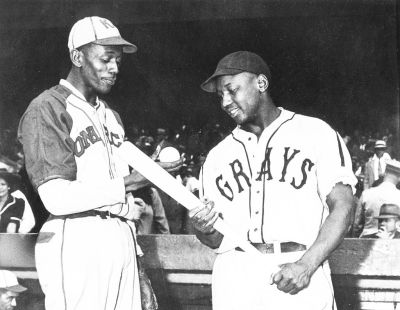

MLB updated its record book to include statistics from seven Negro Leagues from 1920 to 1948. Leaderboards that had been static for years—or in some cases decades—suddenly were shaken up. The most notable newcomer at the top of several lists was Josh Gibson, who played for the Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays from 1933 to 1946, until his death in January 1947 from a stroke.

Josh Gibson is now MLB’s all-time leader in career batting average (.372), slugging percentage (.718), and on-base plus slugging percentage (OPS) (1.177). He also is first in single-season batting average (.466 for the 1943 Grays), slugging percentage (.974 for the 1937 Grays), and OPS (1.435 for the 1943 Grays). He displaced legendary players such as Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, and Barry Bonds on those lists.

“When I saw those numbers, I was like, ‘Wow!’” said Gibson, who got a congratulatory text message from Ruth’s great-grandson, Brent Stevens, the day the news was announced. “Not to say I needed any validation, because I already knew my great-grandfather was a great player, but the stats really put everything into perspective.”

MLB’s decision to include Negro League stats in its database was long overdue. After Jackie Robinson broke the color line in 1947, baseball has been haunted by—and was too often quiet about—its segregationist past. Sean Gibson, executive director of the nonprofit Josh Gibson Foundation and co-founder of the Negro Leagues Family Alliance, hopes putting new names in the record book is not MLB’s final attempt to heal old wounds.

“We don’t want this to be a feel-good moment and then everything goes away,” Gibson said. “It has to be more than just the stats. There has to be some kind of follow-up that will make an impact.”

On June 20, MLB for the first time designated one of its “special events” games to honor the Negro Leagues when the San Francisco Giants and St. Louis Cardinals played at Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Alabama. The oldest ballpark in America, Rickwood Field hosted its first game in 1910 and is one of five Negro Leagues stadiums still standing. MLB invested $5 million to renovate the facility for the game.

Rickwood Field is a poignant reminder of the bigotry that caused the Negro Leagues to exist in the first place and lingered even after baseball was integrated. Reggie Jackson, who played at Rickfield as a minor leaguer in 1967, drove the point home during the MLB on Fox pregame show. “Coming back here is not easy [because of memories of] the racism when I played here, the difficulty of going through different places where we traveled,” Jackson said. “Fortunately, I had a manager and players on the team that helped me through it. But I wouldn't wish it on anybody.”

Although awareness of the Negro Leagues has grown significantly in recent years, it wasn’t until December 2020 that Negro Leaguers were granted major-league status by MLB. An independent committee then took nearly four years to review all the existing Negro League boxscores before MLB signed off on the stats. “This initiative is focused on ensuring that future generations of fans have access to the statistics and milestones of all those who made the Negro Leagues possible,” MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred told the Associated Press.

Manfred is correct, but it raises the question of why it took so long to happen.

“[Integrating the stats] is a positive development and should have been done years ago, but MLB kept avoiding the question of race,” said Rob Ruck, a University of Pittsburgh professor who has authored several books about black and Latin baseball. “I’m just delighted they finally did something. Despite all its deeply rooted inclinations to not deal with reality, sometimes Major League Baseball finally gets it right.”

Sean Gibson / Great-grandson of Negro Leagues star Josh Gibson“We don’t want this to be a feel-good moment and then everything goes away. It has to be more than just the stats. There has to be some kind of follow-up that will make an impact.”

Still, for more than 60 years after rosters were desegregated, the histories of Major League Baseball and the Negro Leagues were sill viewed on unequal terms. Naysayers offered all sorts of excuses—the Negro Leagues played shorter seasons in different sorts of ballyards, had uneven competition levels and spotty record-keeping. Then in September 1988, the Pittsburgh Pirates marked the 40th anniversary of the Grays’ victory in the final Negro Leagues World Series. During a pregame ceremony attended by several surviving members of the Grays and Crawfords— Negro Leagues teams based in Pittsburgh—Pirates President Carl Barger publicly apologized for baseball’s past racism.

“It was the first time a Major League club apologized,” Ruck said. “I think that's when MLB teams started to realize, ‘We can deal with something connected to race without it being dangerous and toxic for us.’”

Yet, progress moved in fits and starts. “Take the Pirates as a microcosm,” said Ruck, who for years prodded the team to honor the Grays and the Crawfords. Both clubs were based in Pittsburgh for most of their existence—the Grays even played some games at Forbes Field, the Pirates’ home field—yet their legacies were mostly overlooked.

In 2006, five years after PNC Park opened, the Pirates created Legacy Square, an area on the street-level concourse that featured statues of seven Negro League standouts—Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, Oscar Charleston, Judy Johnson, Buck Leonard, Satchel Paige, and Smokey Joe Williams—to complement the statues of Pirates legends Willie Stargell, Roberto Clemente, and Honus Wager that are on permanent display outside the ballpark.

Nine years later, however, the Pirates quietly replaced the Negro League statues with banners and remodeled Legacy Square. The ballclub offered to donate the statues to the Josh Gibson Foundation, but storage was problematic and the statues eventually were sold at auction.

Now, Sean Gibson says he will keep up the pressure to prevent the clubs in Pittsburgh and the 29 other big-league towns from backsliding. He’s focused on education, specifically having major league teams to work with local schools and Boys & Girls Clubs to educate people about the Negro Leagues. “That would have a greater impact than simply saying, ‘OK, we’ve integrated the stats,’” Gibson said.

Only two players from the 1920-48 Negro Leagues era are still alive: Bill Greason, 99, and Ron Teasley, 97. Willie Mays died June 18, three weeks after MLB adopted the Negro League stats and two days before the Giants-Cardinals game at Rickwood Field. That ballpark once housed the Birmingham Black Barons, the Negro League team that gave Mays his start in 1948.

Sean Gibson also believes surviving family members deserve a slice of the profits from the sale of Negro League merchandise. “Major League Baseball is going to make money off [selling] Negro League jerseys, right? I get that, because it's a business,” Gibson said. “But, hopefully, there can be some way to help players’ family members get marketing and licensing deals. We've been blessed by having an agent who helps us, but a lot of these people don't have agents.”

The Josh Gibson Foundation has partnered with Ebbets Field Flannels on a Josh Gibson-themed cap and jersey. According to Sean Gibson, the foundation uses a significant portion of its funds to assist more than 300 inner-city kids in Pittsburgh.

The Negro League Baseball Museum owns the rights to many Negro League logos, and sales proceeds are funneled back into the museum, located in Kansas City, Missouri. According to the New York Times, MLB in 1995 donated $143,248 from merchandise sales to surviving Negro League players and to organizations supporting their legacy. Last week, the Major League Baseball Youth Development Foundation, a joint initiative of MLB and the Players Association, donated $500,000 to the Negro Leagues Family Alliance.

The Negro Leagues Family Alliance has asked MLB to designate May 2 as an annual Negro Leagues Day throughout the majors. The first-ever Negro League game was played May 2, 1920, when the Indianapolis ABCs beat the Chicago Giants 4–2 at Washington Park in Indianapolis. MLB already sets aside separate days each season to honor Hall of Famers Robinson and Clemente, who is celebrated for his community involvement and philanthropy.

In 2020, the Baseball Writers Association of America voted to remove former MLB Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis’ name from the plaques given to the American and National League MVP Awards because Landis failed to integrate baseball during his 1920-44 tenure. Sean Gibson requested the awards be renamed in honor of his great-grandfather, but so far the BBWAA has not approved it. Sean Gibson plans to raise the matter again during MLB’s annual winter meetings in December.

“I believe there'll be more things coming from MLB,” Gibson said. “I don't want to doubt it. I honestly think we’re moving in the right direction.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.