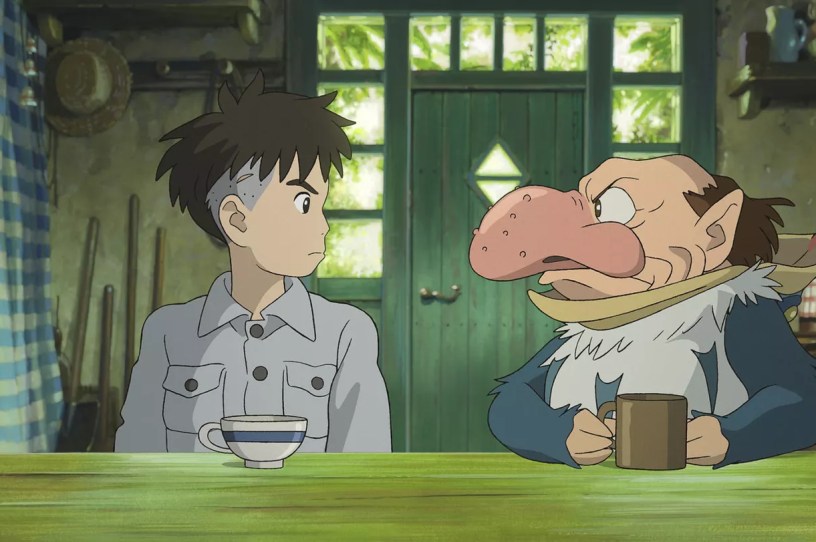

The Artist, ‘The Boy and the Heron’

Over the past few years, devoted anime fans have popularized a meme format that compares the legendary filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki to the horror manga artist Junji Ito. Despite having made a name for himself as an auteur of the kind of Eldritch body horror that would force David Cronenberg to cover his eyes, Ito is actually a pretty upbeat fellow: He dances in public and makes slice-of-life comics about cats as a side gig. Miyazaki, for his part, is best known for the pastel worlds and huggable characters of animated films like My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service, and Spirited Away. But it’s Miyazaki, not Ito, who ambles around chain-smoking and darkly muttering about the cursed nature of humanity’s dreams.

Sifting through the treasure trove of themes and imagery that have come to characterize Miyazaki’s films, despair seems like an unexpected find. Yes, nearly all his works contain carefully woven messages about environmental degradation and the futility of war—understandably so for a Japanese man born in 1941, whose earliest memories were forged in the wake of atomic devastation. But his movies always package serious ideas with charming visuals: adorably diminutive minions that assist his protagonists, food animated with mouth-watering care, scenes involving flight (reflecting a lifelong fascination with aircraft), and oil-like entities whose supernatural nature increases with their viscosity. Alongside this rich visual vocabulary, Miyazaki also offers life-affirming paeans to the importance of friendship, respecting sacred things, and realizing that growing up involves cultivating both inner strength and the ability to see past Manichean labels like “hero” or “villain.”

The Boy and the Heron, Miyazaki’s latest (and purportedly final) film bursts at the seams with nearly all these recurring subjects and motifs. A semi-autobiographical work set in the middle of World War II, it tells the story of a young boy who is lured into a fantastical dimension by an otherworldly heron while living in the Japanese countryside. Although it retreads familiar ground, The Boy and the Heron is nevertheless a deeply personal addition to Miyazaki’s canon. Explicitly connecting the trauma of loss with the power of the artist’s imagination, the film leaves viewers with a moving meditation on art’s redemptive possibilities in the wake of despair.

The film opens with a sea of flames. After losing his mother in a hospital fire, 12-year-old Mahito Maki (voiced by Luca Padovan, who leads a memorable English dub cast) evacuates Tokyo for his family’s traditional estate in rural Japan alongside his father, Shoichi (Christian Bale), and his stepmother, Natsuko (Gemma Chan). Although the peaceful setting somewhat removes Mahito from the conflict, it doesn’t change the fact that his father owns a factory that makes warplanes, or that his stepmother is pregnant with a new baby.

Miyazaki takes his time depicting Mahito’s adjustment to his new life. He lingers on shots of the wind rustling against trees, servants cooking in the kitchen, Mahito slipping out of his shoes before stepping into the imposing entryway of his family’s manor. These moments achingly teem with “ma,” a Japanese term for “emptiness,” which Miyazaki has used to describe how he gives his characters and settings space to live and breathe on their own terms, rather than merely using them to advance the plot.

Struggling with his unspoken grief, Mahito violently hits himself with a rock to get out of school. As he recuperates in his new home, he learns about a great-uncle who disappeared at the turn of the century—after becoming obsessed with alternate worlds and an old stone tower located on the estate. The boy finds himself repeatedly visited by the titular heron (gleefully voiced by Robert Pattinson, doing his best impression of Willem Dafoe’s Green Goblin) who claims it can lead him back to his mother. Mahito resists initially, but after his stepmother disappears, he and an old servant woman named Kiriko (Florence Pugh) are forced to follow the heron into the tower to rescue her.

Up until this point, the film carries itself like a war drama told from a child’s perspective. Its second half, however, turns to the frenetic, stunningly Boschian artistry that has made Miyazaki’s movies famous. Mahito learns that the tower leads to a mystical dimension populated with magicians, spirits, and warring societies of enchanted birds. After a mysterious wizard transports him into a vast ocean, Mahito is rescued by Kiriko. But she’s no longer the old servant he knew; she’s now 50 years younger, and a fearless fisher of giant sea creatures, who uses their meat and guts to feed boatmen-like spirits and unborn souls alike. Encounters with an alien race of pelicans, a fire-wielding girl, and an empire of anthropophagic parakeets all follow, each playing a role in Mahito’s search for his maternal figures.

If all this seems to be a bit hard to follow, well, it kind of is. But narrative coherence has never really been a top priority for Miyazaki, who prefers using hand-painted storyboards rather than scripts, which are often unfinished before his movies enter production. As he explained in The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, a 2013 Japanese documentary about his famed movie company, Studio Ghibli, “I’ve had staff tell me they have no idea what’s going on in my films … The world isn’t simple enough to explain in words.” The Boy and the Heron relishes in casting the straightforward joyfully by the wayside.

Even so, viewers willing to embrace Miyazaki’s dream-logic can expect to receive one of the most enchanting moviegoing experiences in recent memory, one untainted by sequels, reboots, or other enervating products of the American movie industry’s Faustian bargain with intellectual property. That The Boy and the Heron has become the first anime film to top the North American box office chart suggests that Western audiences are starving for original stories that have something daring to convey, instead of endlessly regurgitating the same focus group-tested pabulum (I’m looking at you, Disney).

And beneath the glorious, time-bending, Alice-in-Wonderland weirdness of the film’s second half lies a sober examination of whether we should care about art at all. “How do we know movies are even worthwhile,” Miyazaki has mused, asking whether directors are not damned like the inventors who designed airplanes without realizing they would one day become tools of industrialized warfare. Mahito’s struggles in The Boy and the Heron suggest that the filmmaker might have some serious reservations about what his stories can offer.

At the same time, the world inside the tower is vibrant and captivating, brimming with the kind of life and possibility that Mahito cannot find in the war-torn landscapes of the real world. Nurtured and guided by the wise Kiriko (who exemplifies Miyazaki’s rare gift for creating three-dimensional female characters), Mahito begins reckoning with his all-consuming grief by becoming immersed in the beauty of this mystical world, where he can challenge himself in transformative ways. But even this world is not insulated from pain, as Mahito discovers during a chance encounter with a dying pelican (voiced by Willem Defoe himself).

And the decision Mahito faces at the film’s climax—whether to end his quest in the real world or its magical alternate—might also parallel Miyazaki’s own thoughts about how we should approach art in the first place. One way of understanding The Boy and the Heron is as a metaphor for the director’s artistic journey. The heron and the wizard respectively serve as stand-ins for Miyazaki’s producer, Toshio Suzuki, and his late mentor and Studio Ghibli co-founder, Isao Takahata. Although Miyazaki clearly cares for his long-time collaborators, the film highlights important tensions in these relationships, depicting how the heron and the wizard alternately manipulate and assist Mahito when he’s drawn into the tower.

There is a reason that there are no “Ghibli adults” in the same way that there are “Disney adults.” Disney gives audiences an escape, while Miyazaki has spent his career trying to give them an education. I was 9 years old when I saw Spirited Away, and I will never forget the feeling of having seen a movie that, for the first time, was taking me by the shoulders and trying gently, but urgently, to tell me something important about love, and courage, and so many other keys to a good life. The Boy and the Heron reminds us that a good life depends on moments of reenchantment one can often only find through art—but it also cautions against art’s darkly seductive capacity for self-delusion and therefore self-destruction. Yet by highlighting beauty within a broken world, the best art gives us the means to face life’s inevitable tragedies head-on, instead of merely running away from them. After 40 years of teaching us this truth through his art, The Boy and the Heron may be Miyazaki’s last attempt to ensure that the lesson sticks.