“Shields up,” the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency (CISA) warned this week. The White House has threatened to impose punishing financial sanctions on Russian banks and restrict key technology exports to deter further Russian aggression against Ukraine, but if the seemingly inevitable happens—Moscow invades, Washington responds, and Moscow parries back—is America prepared to withstand the onslaught? There is no indication the Biden administration, or its predecessors, have ensured the answer is yes.

The Kremlin has ignored prior slaps on the wrist—after it seized Crimea in 2014 and after the Skripal poisoning in the United Kingdom in 2018—and so the new sanctions will need to be economically devastating. Back in 2018, then-Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev called sanctions “a declaration of economic war,” and pledged that Russia would “react to this war economically, politically, or, if needed, by other means.” With a limited ability to retaliate with its own financial sanctions, the Kremlin may turn to cyberattacks. In the U.S. government’s own words, “The Russian government understands that disabling or destroying critical infrastructure—including power and communications—can augment pressure on a country’s government, military and population and accelerate their acceding to Russian objectives.”

DHS warned U.S. companies last month to bolster their cybersecurity. While hardening corporate America’s cyber defenses is essential, robust planning requires having contingencies for when defenses fail. The U.S. government must be ready to help the American economy recover rapidly after a significant cyber event, which could simultaneously bring down the power, water, banking, and telecommunication sectors.

Congress had precisely this type of crisis in mind last year when it tasked the Biden administration with crafting a Continuity of the Economy (COTE) plan. Such a plan would identify the optimal steps toward recovery and prioritize the flow of goods, services, information, and resources to the most critical sectors of the economy while accounting for their overlapping requirements and interdependencies.

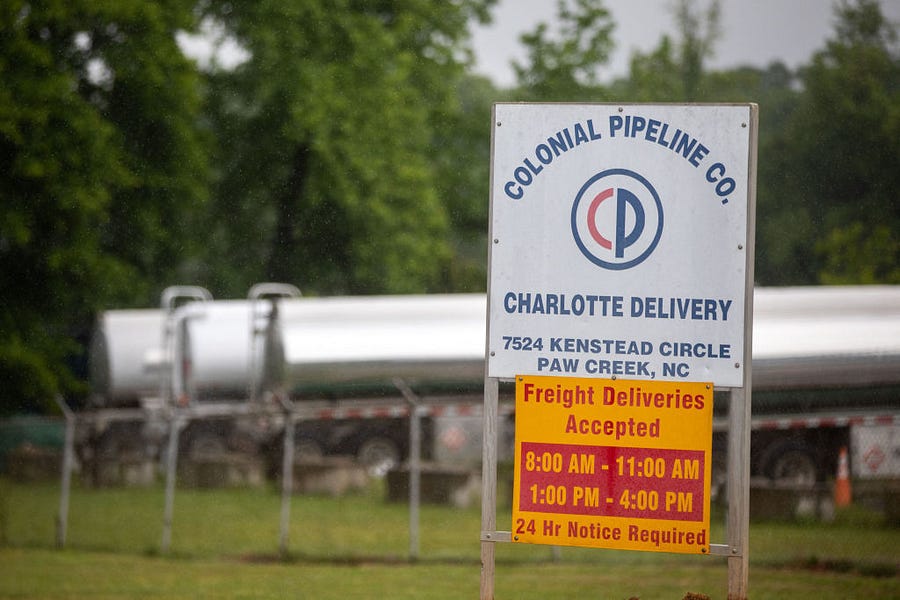

The Kremlin’s state-backed hackers have long shown a penchant for critical infrastructure attacks. The Kremlin has been laying the groundwork for attacks against U.S. critical infrastructure for years by installing malware into the U.S. power grid. A “digital blitzkrieg,” as Wired magazine described it, of more than 6,500 attacks between 2015 and 2017 repeatedly left hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians without electricity and halted Kyiv’s State Treasury systems for days. Russian gangs, meanwhile, triggered a regional state of emergency when a ransomware attack shut down Colonial Pipeline and disrupted fuel supplies on the East Coast and southeastern U.S. last May.

If Washington enacts harsh sanctions in response to an invasion of Ukraine, Russia will leverage its previous hacking campaigns to launch something new and destructive. In anticipation, Russian hacking units tied to the GRU have developed “more sophisticated means of critical infrastructure attack[s],” according to John Hultquist, a cyber intelligence analyst at Mandiant.

Even if Russia does not launch a direct cyberattack on the United States, American companies may be collateral damage from Russian cyberattacks targeting Ukraine or Eastern Europe. In 2017, a Russian cyberattack known as NotPetya, which initially targeted Ukraine, unintentionally spread through thousands of connected devices, taking down banks, pharmaceutical companies, and logistics operations throughout Europe. Causing an unprecedented $10 billion in damages around the world, the attack shut down the operations of major companies like the shipping giant Maersk, the pharmaceutical corporation Merck, the food company Mondelez, and FedEx’s European counterpart, TNT Express.

Maersk, which accounts for close to a fifth of the world’s shipping capacity, including 76 ports and more than 800 vessels containing tens of millions of tons of cargo, had to reinstall 4,000 servers, 45,000 PCs, and 2,500 applications over the course of 10 days. Merck ceased manufacturing, research, and order fulfillment for several weeks after the attack. One Merck researcher said she lost 15 years of work because of the NotPetya attack, and the company had to borrow doses of of its HPV vaccine from the Centers for Disease Control’s stockpile. FedEx was still recovering from NotPetya six months later. Today, in a world of increasing automation and digitalization, buffeted by a global pandemic and supply chain issues, the NotPetya could have even more dramatic consequences.

In the wake of NotPetya and other global attacks, Congress created the Cyberspace Solarium Commission to help Washington devise a better strategy in cyberspace. This commission recommended the development of COTE planning, and Congress gave the Biden administration two years to develop a strategy for generating a COTE plan. One year in, there is little evidence that the work has started. The crisis in Ukraine is once again demonstrating how vulnerable the highly networked U.S. economy is to catastrophic cyberattacks, and how much a COTE plan is needed to build resilience and speed up infrastructure recovery.

The creation of a comprehensive COTE plan in the coming weeks and months is not realistic. In the short term, the administration must rely on existing state and local arrangements for responding to emergencies while leveraging CISA to assist the Federal Emergency Management Agency. In the longer term, however, there will be no excuses for an administration that allows the U.S. economy to come under cyberattack without a plan in place for its rapid recovery.

Mark Montgomery is senior director of the Center on Cyber and Technology Innovation (CCTI) at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD). Samantha F. Ravich is the chair of CCTI. They served as executive director and commissioner, respectively, on the congressionally mandated Cyberspace Solarium Commission. FDD is a Washington, D.C.-based, nonpartisan research institute focusing on national security and foreign policy.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.