Wedding bells have been ringing ever less frequently in America.

This may seem like a personal problem to some, but marriage has always had political implications in addition to romantic and cultural ones. Lower fertility rates pose serious fiscal and social risks. Single parenthood exacerbates inequality and stifles opportunity. And detachment from personal bonds has correlated with an ongoing increase in loneliness—now a recognized public health crisis. The downstream consequences of decreased marriage will be felt for a long time to come.

Yet warnings about infrequent nuptials have for years been downplayed. It’s not always clear what politicians can do about it, some say. Others question why we’d want to do something in the first place. Rebecca Traister, writer-at-large for New York magazine, reflected this more left-wing approach to the conversation around marriage, lamenting how “policymakers have routinely imposed marriage — as if it were a smooth, indistinct entity — as a cure for the inequity, dissatisfaction, and loneliness that plague this nation.”

Policymakers may not be able to easily put any of the various genies keeping people from tying the knot back into their various bottles. Moreover, marriage inevitably touches on personal questions of purpose and identity that can make it an awkward fit for a technocratic policy agenda. But the role and function of marriage is too important for politics to treat with a mere benign agnosticism. Understanding why marriage has become less commonplace can help us avoid wrong turns in trying to shore it up.

Arguments about what marriage is or should be are nothing new. As the historian Stephanie Coontz argued in her book Marriage, A History, the idea of marriage being in “crisis” stretches back as far as the institution. “The ancient Greeks complained bitterly about the declining morals of wives. The Romans bemoaned their high divorce rates … [while] settlers in America began lamenting the decline of the family” shortly after Plymouth Rock.

Most of the pre-Obergefell political oxygen around marriage focused on its definition (or redefinition). Those debates hinged on the purpose of the institution: Should marriage be something oriented toward fidelity, permanence, and procreation? Or something that celebrates romantic affection, identity, and companionship?

But with the benefit of hindsight, it’s somewhat odd that the United States exerted so much time and energy on the definition of marriage at the moment fewer people than ever were walking down the aisle. In the 2000s and 2010s, as the idea of marriage was undergoing a legal metamorphosis, marriage rates continued their long, downward slide. In the 1970s, America saw about 11 weddings for every 1,000 people. Last year, it was 6 per 1,000.

Some of this is a function of increased life expectancies, some of an aging population. But something has changed culturally as well. What was it?

In short: Marriage ceased to offer goods that were once exclusive to it. Men became less appealing as mates relative to the economic purchasing power of single-mother households. Perhaps more speculatively, the culture demoted marriage from being the sole normative path for adults to simply being one option among many.

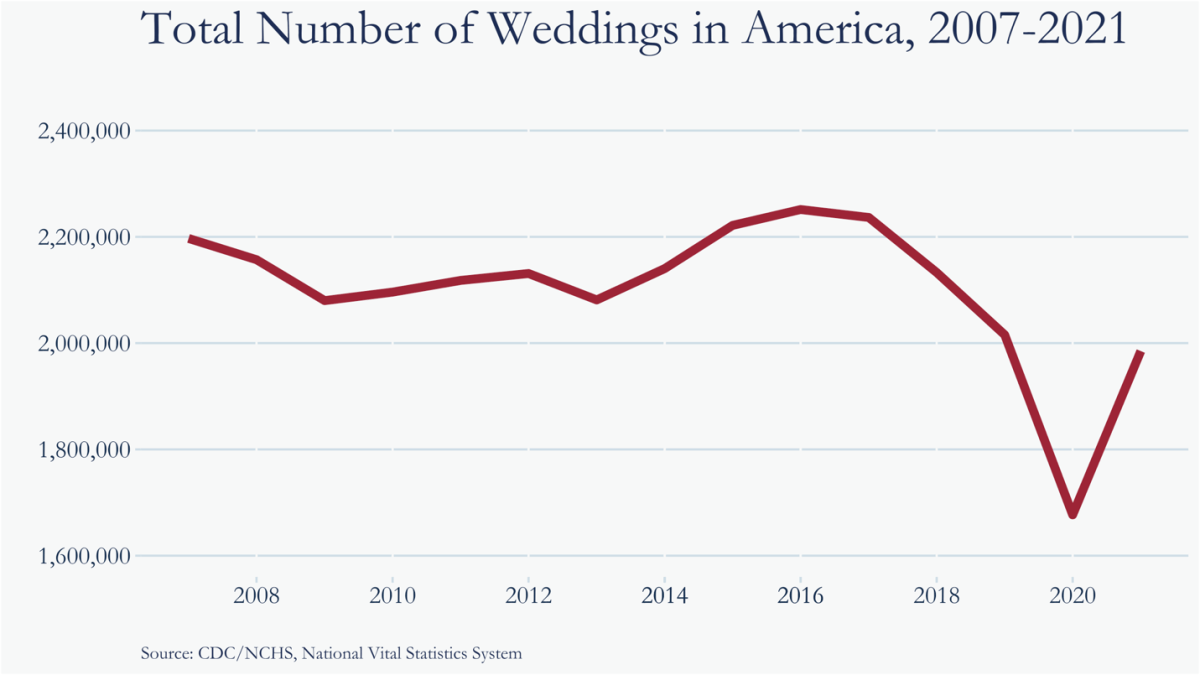

First, some numbers. Over roughly the past decade and a half, the U.S. population grew by 30 million people, but the number of weddings has not grown apace. In 2007, nearly 2.2 million couples married; in 2021, the tally stood at 1,985,072. A dip in annual marriages might be expected in the wake of the Great Recession. Certainly, many couples postponed tying the knot—voluntarily or involuntarily—during the height of COVID (resulting in an apparent post-pandemic bump).

But note that on this graph, the U.S. hit “peak wedding” in 2016. Both 2018 and 2019 saw 100,000 fewer weddings than the year prior. Before anyone in the U.S. had ever uttered the word “coronavirus,” and while the economy was delivering strong results to workers across the income spectrum, marriage continued its long, downward trajectory.

Marriage was once necessary for financial stability, social advancement, sex, and procreation. Now, it’s clear that cultural, legal, and economic changes have made it less central in all four of those areas of life.

The average age at first marriage continues to increase. Many couples can and do cohabitate for long periods of time, even permanently, without finalizing their bond with a trip to the county courthouse. And as Johns Hopkins University sociologist Andrew Cherlin wrote nearly a decade ago, marriage has become “a highly regarded marker of a successful personal life.” He went on:

Today, marriage is more discretionary than ever, and also more distinctive. It is something young adults do after they and their live-in partners have good jobs and a nice apartment. It has become the capstone experience of personal life — the last brick put in place after everything else is set. People marry to show their family and friends how well their lives are going, even if deep down they are unsure whether their partnership will last a lifetime.

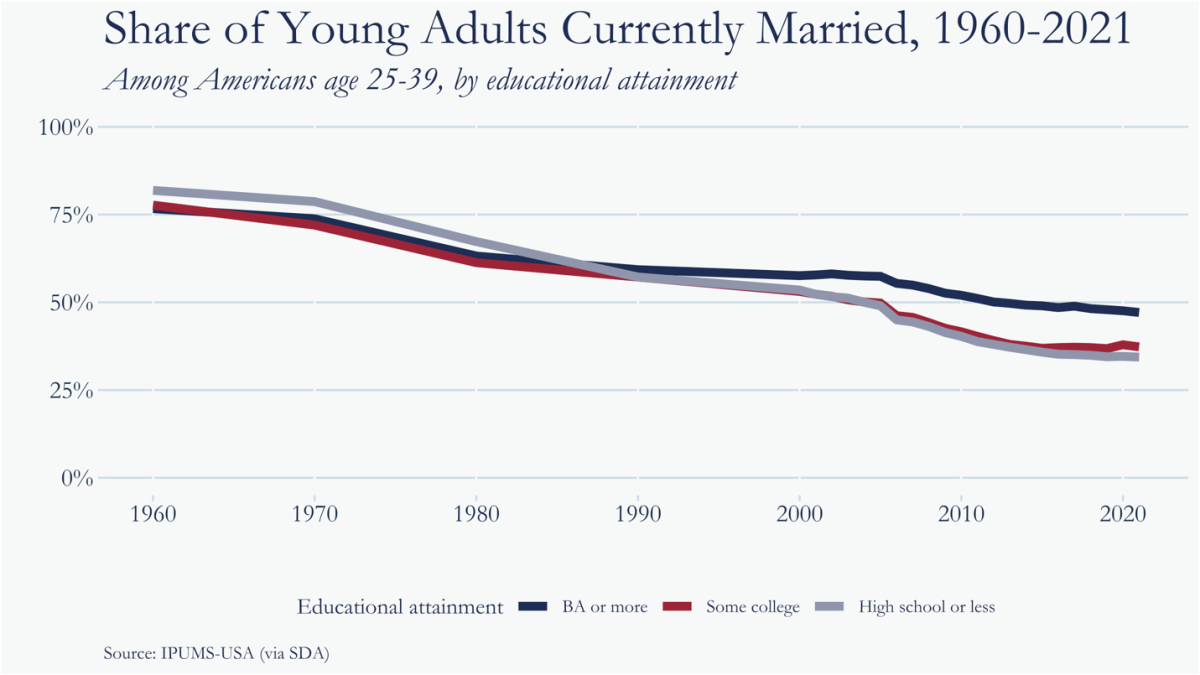

If having a wedding is a status symbol, no wonder it’s become what economists call a “luxury good,” something you consume as your income rises. College-educated Americans are still benefiting from the stability and “privilege” offered by married family life. Those without a college degree, by contrast, are not. Men with a high school degree divorce at a rate twice as high as men with an advanced degree. And fewer working-class Americans are getting married in the first place. More than three-quarters of young adults with only a high school degree married in 1970, compared with about one-third last year.

A recently released paper by Jeanne Lafortune and Corinne Low illustrates that the introduction of no-fault divorce and similar “policies that erode the marriage contract in other ways will make wealth a more important determinant of marriage.” The authors find that for working-class couples, making it easier to leave a marriage has meant that tying the knot leads to fewer economic benefits. For wealthier couples, on the other hand, “having assets [like owning a home] allows marriage to retain value—through increased commitment and protection for the lower earning spouse—even in the presence of one-sided divorce.”

As these divides in marriage have grown, some academics and policy practitioners have sought to both sound the alarm and search for causes. The most recent case is Melissa Kearney’s The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind, in which she asks an essential question to understand the marriage decline puzzle.

Kearney points out that among mothers without a college degree, about 70 percent of children are born to unmarried parents: Dad may be cohabiting but is not legally committed to Mom. Can it really be the case, she asks, that some or even many of these children are being “fathered by men with no positive resources to contribute to a family environment?” This is a fundamental problem to reckon with: Why are so many men “not fit to be marriage partners or engaged fathers”?

Shifts in the U.S. labor market explain part of the story. Men without college degrees now bring less to the table than they may have in prior generations. Kearney writes that, “The ‘gains to marriage’ will depend not just on how much he would bring, but on how much she could make on her own.” As women’s labor force participation increased and labor market outcomes for blue-collar men stagnated, women became more willing to go it alone. This is not a question about whether male wages have declined, but rather what they have done relative to wages for female workers. AEI’s Scott Winship suggests that men may have once received a “breadwinner premium” that eroded as women entered the labor market.

Kearney doesn’t want to turn back the clock on the ability of women to earn a living (nor do Winship or I). But the knock-on effects of the economic changes between the sexes are real—a “vicious cycle,” in Kearney’s words:

The forces that have eroded the economic position of non-college-educated men are now having widespread, multifaceted effects on families and how children are raised. These affected children are straddled with disadvantages that make it harder for them to flourish. The changes in family structure lead to further inequality and cement class gaps across generations.

More than 25 years ago, Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Dan Quayle were pilloried for their concern about the stability of black families. They and their critics, however, had no way of knowing the same trends—joblessness, fatherlessness, and nonmarital births—would no longer be exclusively a problem of minority households in inner cities just a few years later. Over the first two decades of the 21st century, previously high marriage rates in the South converged with much of the rest of the country. In Kentucky, Alabama, Texas, South Carolina, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Tennessee, rates fell by roughly a third.

In addition to the economic trends weakening marriage, our popular understanding of what marriage is and what it’s for has shifted as well. In 1962, the share of American mothers who felt that “all married couples who can, ought to have children” stood at 84 percent; two decades later, that share stood at 43 percent. A 2023 survey from the Pew Research Center found only 5 percent of Americans say a husband and wife choosing not to have children is somewhat or completely unacceptable.

Rather than being a social default, marriage now requires an affirmative choice, raising the stakes of what it can mean for an individual. Divorced from an orientation toward permanence and a capacity for procreation, this self-expressive emphasis helps explain how the hot-button marriage debates of the 2000s and 2010s unfolded. It also helps make sense of why some might be putting off marriage.

Why formalize a casual union if doing so forecloses other possibilities that could lead to even greater happiness? Marriage as a “capstone” reflects a passage through young adulthood into a time for settling down (partly reflected in today’s low divorce rates). Surely part of the decline in marriage could be attributed to some people holding marriage in such high esteem that they feel reluctant to commit themselves to it until they feel financially secure, their wild oats sown, and open to trading off some optionality for stability in their relationships.

But turning marriage into merely a certificate for a successfully completed young adulthood, with no internal logic, leaves it open to any manner of interpretations. Half of Americans aged 18-29 told Pew they see open marriages as an acceptable arrangement for people to have. Three-quarters of those under 50 said an unmarried man and woman raising children is an acceptable arrangement, compared to two-thirds of those 50 and over. If marriage’s form and structure has no inherent link to the way we raise our children or the bonds we form with our spouse, of what use is the institution?

Progressives tend to argue the institution should have no inherent privileges at all, beyond that which the two (or more) consenting participants want to imbue it with. Conservatives tend to want to bring back higher marriage rates without necessarily having a vision for making the family more necessary and less replaceable. Economics may not be the only factor determining marriage, but expecting a renaissance without better prospects for men without college degrees and more affordable pathways to household formation (like housing) is wishful thinking.

Marriage is not a cure-all, but it is a vital source of stability for children and of meaning for adults. Married adults are more likely to thrive along a number of dimensions. As Kearney’s book covers in extensive detail, children who grow up in a two-parent household experience better outcomes. And they are not the only ones who benefit: Harvard’s Opportunity Insights lab has found that the share of married parents in a neighborhood is one of the characteristics most strongly associated with economic mobility for low-income youth.

No one will get married because a politician tells them to. But making marriage more economically viable and socially vital requires treating marriage as a political problem and thinking about what purpose it ultimately serves. Reviving marriage must include a focus on its benefits, yes, but also some frank talk about its purpose as an institution and a clear-eyed assessment of the economic, legal, and cultural trends that have contributed to its decline. Only then can we start to rebuild.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.