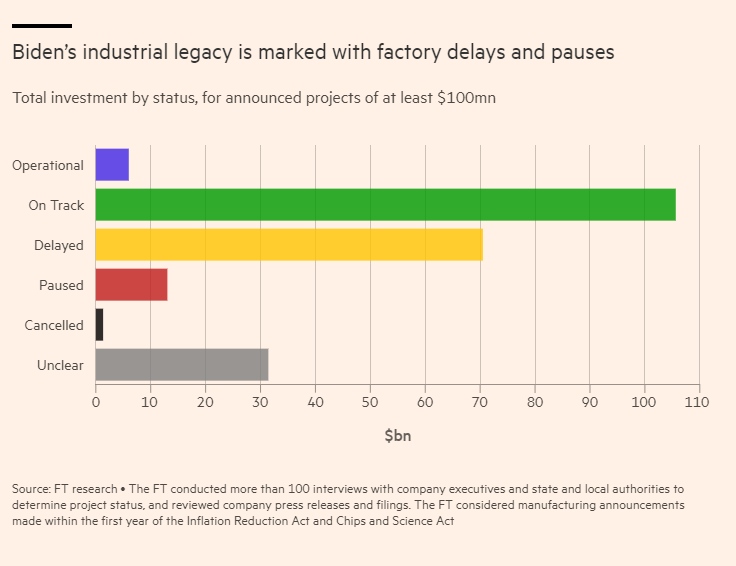

Last week, the federal CHIPS and Science Act turned two years old, and—like most toddlers—there’s things to like and things that keep you up at night. On the plus side, the tens of billions of dollars in grants, loans, and tax credits authorized by the law appear, as we discussed a few weeks back, to have encouraged global chipmakers to build (or at least promise to build) new manufacturing facilities (“fabs”) in the United States, as evidenced by a large uptick in manufacturing construction spending since 2022. On the other hand, we just don’t yet know whether this spending will translate into a vibrant, cutting-edge U.S. semiconductor industry. As economist Joey Politano just documented, in fact, there’s currently a disconnect between elevated spending on chipmaking buildings and still-tepid spending on the (very expensive!) equipment needed to actually make those chips. So, the jury’s still out on what’s actually going to go into the massive structures now being built.

That question should get resolved in the coming months as the shells get completed. Bigger CHIPS questions, however, will remain. And Intel—the top recipient of CHIPS subsidies and, per the Biden administration, our national champion—is perhaps the biggest one of all.

As you may have heard, Intel’s not doing so hot. As part of the company’s latest earnings report, CEO Pat Gelsinger announced that the company had not only lost $1.6 billion last quarter but also planned to cut 15,000 jobs (more than it promised to create under CHIPS), to pause dividend payments, and to substantially reduce capital expenditures this year and next. Since then, Intel’s already-foundering stock fell even further. As of August 10, in fact, Intel’s shares were down 68 percent since Gelsinger first announced his big “turnaround plan” in 2021. (The S&P 500 has gained 39 percent over the same period.) Intel’s stock is now trading below “book value” for the first time since at least 1981, when folks first started tracking this statistic, meaning that “investors are now valuing one of the world’s largest chip manufacturers for less than the value of its facilities and other assets on its balance sheet.”

Yikes.

For many in Washington, the CHIPS Act’s success or failure will hinge on Intel. Should the company recover from its current tailspin, the subsidies will undoubtedly be given much of the credit; should it fail, it’ll be Solyndra on steroids. But that calculus is in my view too simplistic: The real question isn’t what happens to Intel next; it’s how we got here in the first place—and how the CHIPS Act all but guaranteed that we would.

Intel’s Troubles, Past and Current

For anyone paying attention to the global semiconductor industry in recent years (and who hasn’t?!), Intel’s current troubles are hardly surprising. Indeed, one of CHIPS advocates’ dirty little secrets is that the current absence of American-made semiconductors at the industry’s bleeding edge—a common pro-CHIPS talking point—isn’t owed to a lack of U.S. industrial policy or “strategic” government planning (or whatever) but instead to one simple thing: Intel’s repeated production failures in the 2010s. As I explained in 2020, in fact, the U.S. semiconductor industry was still bragging as late as 2019 that it was (in their words) “essentially neck-and-neck [with Korea and Taiwan] in logic process technology as all three nations have raced to bring leading-edge 7/10 nm technology to market.” (Nanometers [nm] are how logic chips are usually classified: the smaller, the better.) It subsequently became clear, however, that the United States had lost its top spot in the global “nanometer race” because Intel couldn’t get its act together at 10nm. Since then, the technology has zoomed ahead but Intel seemingly hasn’t:

Troubles with bleeding-edge process technology are not, however, Intel’s only problem. As CNBC, The Economist, the Wall Street Journal, Reuters, and other outlets have detailed, the company that once dominated global chipmaking has made repeated bad bets over decades about the future of the global semiconductor market and Intel’s role therein. This includes:

- Stubbornly refusing to embrace the industry’s increasingly bifurcated approach, in which “fabless” companies like Nvidia specialize in design and then outsource their manufacturing to specialized “foundry” companies like TSMC. Instead, Intel until very recently insisted on designing and building only its own chips and rejected requests from fabless companies to produce theirs. This has been widely seen as a massive and costly strategic mistake.

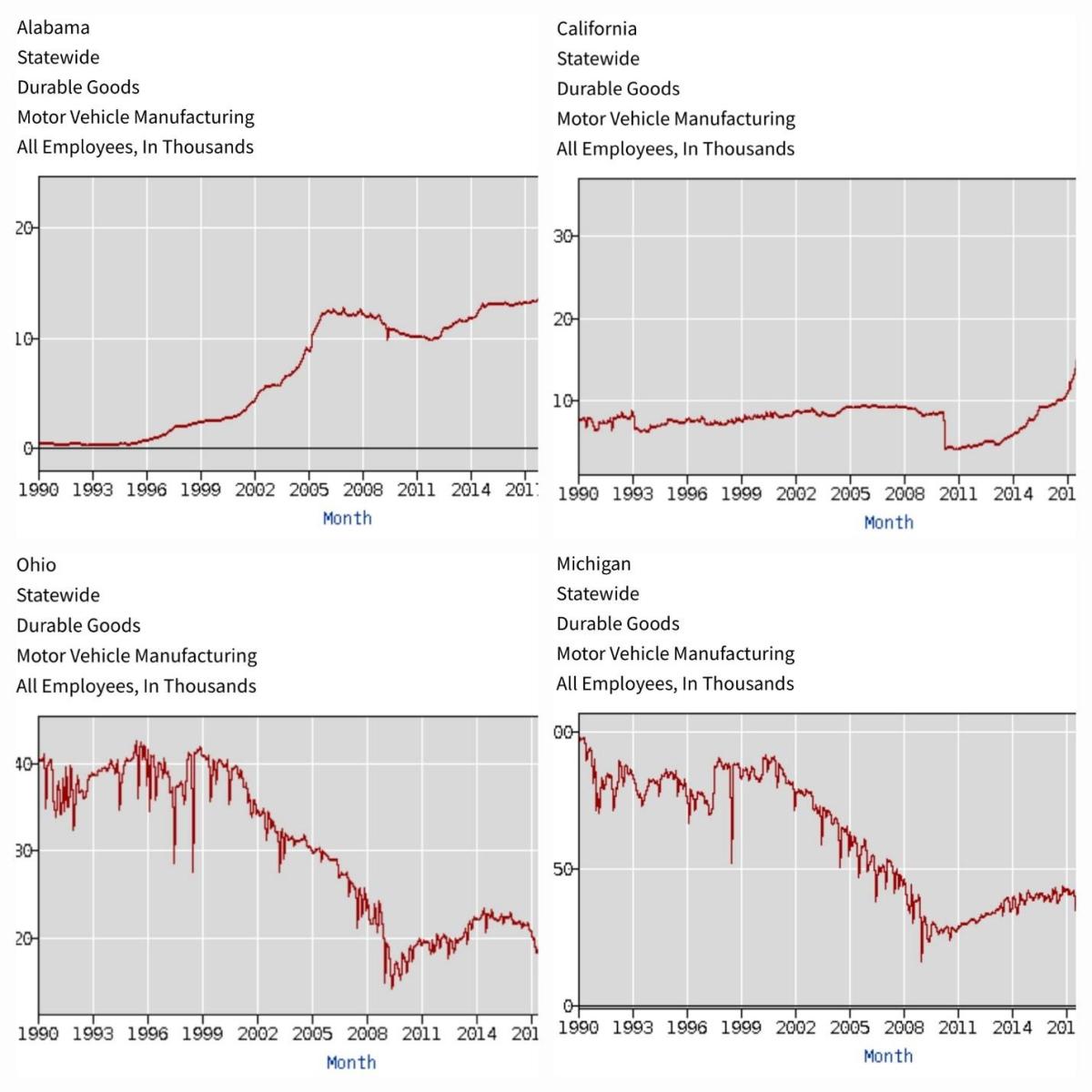

- Missing the seismic industry shift from PCs to smartphones in the late-2000s (and even refusing a tie-up with a little company called Apple that was about to release this thing called an iPhone)—a miss that would eventually harm its dominant PC business too.

- Most recently, missing the explosion in demand for artificial-intelligence chips (and even missing out on a chance to invest in ChatGPT creator OpenAI, which has since teamed with Microsoft). As AI researchers in the 2000s turned to graphics processing unit (GPU) video-gaming chip architecture, which is used by AI leaders Nvidia and AMD, Intel clung to its central processing unit (CPU) approach. Since 2010, the company has spent billions on trying to produce a viable AI chip but has repeatedly failed. Per the Journal, in fact, Intel was still making this mistake when plotting its revival: “The rapid shift to spending on AI…wasn’t something contemplated when Intel laid out an ambitious and expensive plan to catch up its manufacturing processes to those of Taiwanese rival TSMC three years ago.”

These systemic problems have persisted for decades and drive Intel’s latest financial woes, which appear to run deeper than the headlines lead on. “Intel's financial condition and trends frankly look terrible,” said one investor, pointing to high levels of debt and low levels of revenue (especially compared to other semiconductor companies), poorly performing investments, and a rapidly deteriorating cash flow situation. To top it all off, Intel’s shareholders are now suing the company for supposedly misleading them about how well Gelsinger’s turnaround plan was going.

It’s not a pretty picture—at least not right now.

Failure Rewarded

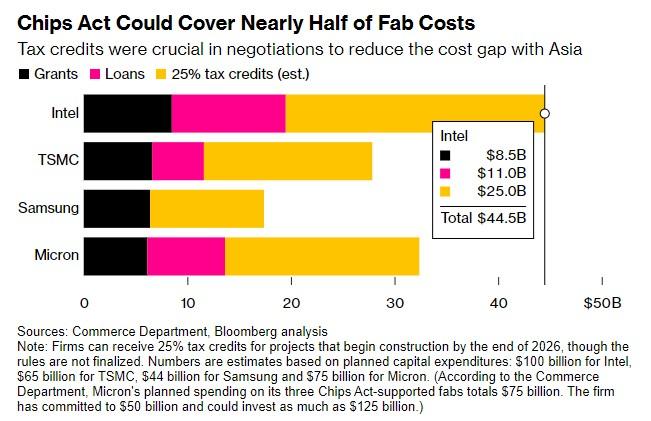

So, Intel’s problems have been known for decades and run deeper than just some quarterly revenue miss (though losing $1 billion-plus in a single quarter when your competitors are killing it isn’t exactly good news). Yet the U.S. government’s response to these challenges has effectively been to throw the company a big parade. It was the top recipient of CHIPS Act funding this year—a collective taxpayer commitment of as much as $44.5 billion in grants, loans, and tax credits. (Ohio taxpayers are potentially on the hook for billions more.)

When those subsidies were announced in March, President Joe Biden held a big celebratory press conference in Arizona championing the payout. At the same event, Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, whose department was in charge of selecting subsidy recipients, called Intel “America’s champion semiconductor company”—a name she reiterated in a subsequent NPR interview at which time she elaborated that “we're excited to be backing them” because Intel is “the only U.S. company that can make leading-edge chips.”

In theory, at least.

In reality, however, we still don’t know if Intel actually can make those chips—at least not at commercially viable quantities and prices. Along with everything already discussed, in fact, Bloomberg reminds us that the epicenter of Intel’s turnaround plan isn’t exactly a prime spot for semiconductor production:

The crown jewel of the expansion is a sprawling Ohio complex that Intel has said will become the world’s largest chipmaking facility, and which President Joe Biden has called a “field of dreams.” Pulling it off was always going to be a challenge. There isn’t much of a semiconductor ecosystem in the state, and it’s not clear whether Intel has lined up any customers.

Intel Ohio might have supplier concerns too: Several big names promised to open facilities there but have recently gone quiet. (Can’t exactly say I blame them.)

It’s all enough to wonder why Ohio was chosen in the first place. Hmm.

Anyway, if Intel continues to falter, it’ll be a big, BIG problem for the CHIPS Act and related strategic objectives, because—as I explained to the Joint Economic Committee a few weeks ago— the other “Big Three” chipmakers haven’t fully committed to bringing their bleeding edge technology here and might never do so:

TSMC’s first Arizona facility will produce 4‑nanometer chips in relatively small volumes (20,000 wafers per month) when it begins commercial production in mid-2025, but the company is already producing 3‑nanometer chips in Taiwan in much larger volumes (100,000 wafers/month this year) and intends to begin mass producing 2‑nanometer chips there next year. Samsung will also reportedly begin 4‑nanometer production in Texas in 2025, at which time the company will be moving to 2‑nanometer production in Korea. Both companies have also reported substantial cost overruns at their U.S. facilities—costs that they may pass on to U.S. customers. (TSMC’s U.S. chipmaking operations reportedly cost 50 percent or more than they do in Taiwan.) The companies’ executives also have repeatedly maintained that they will keep “the most cutting-edge chip fabrication technologies in their home countries.” National champion Intel, meanwhile, has suffered setbacks in advanced chip production since at least 2018, and many analysts today question the company’s ability to catch industry leaders like TSMC and Samsung.

That last line was written before Intel’s latest financials came in. Investor doubts have thus only gotten louder.

So, what exactly are “we” (in Raimondo’s words) celebrating here?

It’s the Incentives, Stupid

That Intel received so much taxpayer money in the face of so much contrary evidence is right out of the Industrial Policy 101 textbook—and past editions of Capitolism. As we’ve discussed, both distant and recent U.S. policy history is littered with examples of “national champions” successfully using their reputations, “strategic” and geographic clout, political connections, and deep pockets to win massive subsidy payouts, regardless of the actual merits. (Here’s a brand new example in the solar industry.)

Politicians, meanwhile, typically aren’t motivated by some mythical “public interest” but instead by their own personal ambitions—getting reelected, winning a sweet job on K Street or in the C-suite, etc. They’re also unencumbered by the usual checks that the market places on private investment. As Milton Friedman reminded us years ago, people spend differently when it’s not their money or lives on the line, and, far from punishing politicians for wasting taxpayer money on subsidized boondoggles, voters often reward them just for trying (assuming they even notice at all). Indeed, for all the noise about Solyndra, it’s not like it cost President Barack Obama, Vice President Biden, Speaker Nancy Pelosi, or Leader Harry Reid their jobs. Far from it.

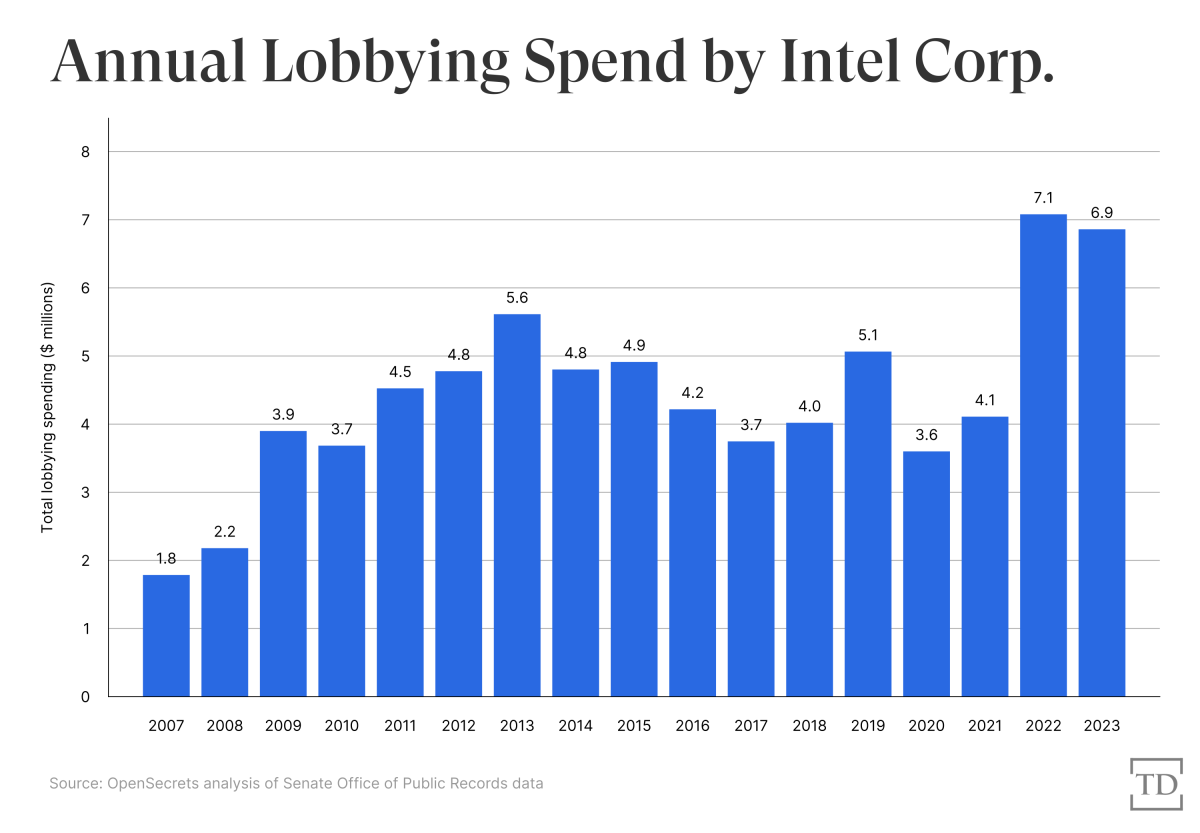

Given these incentives and Intel’s own history (and lobbying efforts), the approval of CHIPS two years ago all but guaranteed the company a huge subsidy payout, regardless of the merits.

Throw in the chance for big, ribbon-cutting photo ops—replete with golden shovels and maybe giant scissors too—in both electorally important Arizona and Ohio (ohhhh, now I get it!), and it’s a wonder the company didn’t get even more.

Of course, the Commerce Department promises us that it won’t throw good money after bad on Intel, most recently “seeking reassurance that … projects in New Albany [Ohio] and three other states are moving forward, despite the company’s recent announcement that it’s slashing 15% of its workforce.” Color me skeptical, as the same political incentives that drove Intel’s record subsidy award—one that came in the face of decades of contrary evidence—will undoubtedly affect government decisions as to whether to keep subsidizing Intel in the future.

And, in fact, the CHIPS Act has almost certainly made those bad incentives even worse.

As The Technology Pork Barrel laid out decades ago, one of the biggest problems with past U.S. industrial policy was that federal dollars kept flowing to projects for years after their failures had been evident, costing billions more and crowding out better projects. This isn’t just a historical problem either: Last year in New York, for example, state and local officials were still pushing a highly subsidized and still-mostly-empty Tesla solar panel factory on the weakest of grounds: They literally said it’s better than nothing, and that they “want” it to succeed in the future. Disinterested observers, on the other hand, call it “the single biggest economic development boondoggle in American history.”

That conclusion could admittedly be an exaggeration, given all the other choices.

Every case, however, tells a similar industrial policy story: American politicians, bureaucrats, and outside pundits and wonks stake their careers and reputations on these big projects, and new beneficiaries— companies, unions, local officials, etc.—emerge to defend them to the bitter end. Everyone thus becomes heavily invested, professionally and perhaps emotionally, in not just subsidizing boondoggles but also keeping them afloat or even expanding them long after the market has ruled them unfit.

For Intel and CHIPS, there’s surely reason to worry that history’s repeating again. The U.S. government, especially the Biden administration folks who have championed these funds and Intel at every turn, has strong incentives to keep the money flowing, as long as Intel doesn’t publicly collapse. Because a good chunk of the federal and state money at issue here—tax credits, infrastructure, etc.—either has been or soon will be spent, regardless of actual company performance, the good ol’ sunk cost fallacy will surely be at play too. (“We can’t stop now; we’ve already spent so much!”) Topping it all off is the “national security” card, which subsidy recipients often use but, as Bloomberg reminds us, has special significance here because Intel got another few billion for just that reason:

[T]here’s more at stake if Intel can’t deliver. The company is also the sole intended beneficiary of a $3.5 billion Chips Act program to make advanced electronics for the military, an effort called the Secure Enclave. The idea is to create a separate, locked-down area within Intel’s factories to make semiconductors for top-secret defense purposes. It’s caused a furor in Washington, in part because it entrusts the responsibility to one company.

Indeed, as the Journal just noted, the company’s one trump card is that the U.S. government (mainly via CHIPS) has deemed semiconductors to be a strategic security priority, and only Intel’s facilities are primarily located in the United States. The company may thus be “too big to fail,” regardless of its many problems.

Together it’s a recipe for endless subsidization and, if history is any guide, maybe tariffs too. No surprise, then, that Intel was already lobbying Congress for new subsidies just days after its original $45 billion in handouts were announced.

I mean, sure it’s gross and all, but if you were Intel … wouldn’t you?

Summing It All Up

In the case of a legitimate market failure or national defense concern, one can reasonably make the case for government involvement. In semiconductors today, in fact, it might make sense for Washington to offer direct subsidies or long-term procurement contracts to ensure a stable, local supply of the chips the U.S. military needs for weapons systems and similar things. Something like that “secure enclave” program—administered by the Defense Department, time- and cost-limited, and subject to substantial transparency and oversight—might therefore be necessary. It would still raise risks, of course, but they’d be relatively small and confined to a sector that has no private market alternatives. In such a situation (and assuming various supply-side reforms were also pursued), not even I’d be complaining—at least not much.

That is, of course, decidedly not what we have today with the CHIPS Act—and, barring a miraculous Intel revival, it’s probably not what we’ll have in the future, either. Instead, we have a sprawling law showering countless billions on numerous companies for ambiguous ends. A law that gave a notoriously struggling “champion” a record award to much political fanfare, just because the company is ostensibly “American” (never mind its many overseas investments, including in China). And a law that, if Intel’s stock price is any indication, might soon put federal policymakers in the unenviable position of choosing between further subsidizing a has-been zombie, with all the additional waste and distortion that entails, or being blamed by voters for a “champion’s” demise when the federal gravy train runs out and no real alternatives have emerged—perhaps because those same subsidies crowded them out.

Little of this, however, is Intel’s fault—it’s the fault of the CHIPS Act and other laws like it, and the many bad incentives they’ve inevitably created. Until those things are fixed, it’ll be more of the same, whether Intel’s alive to see it or not.

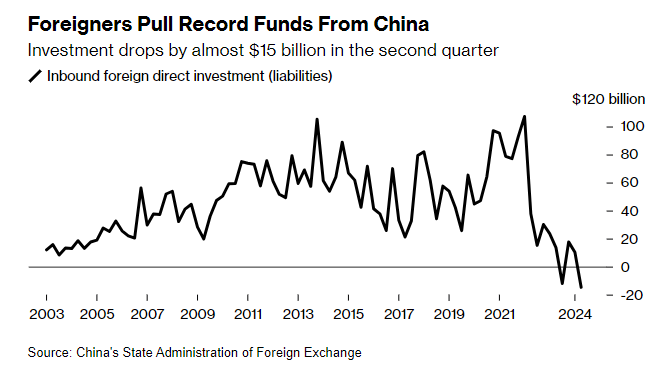

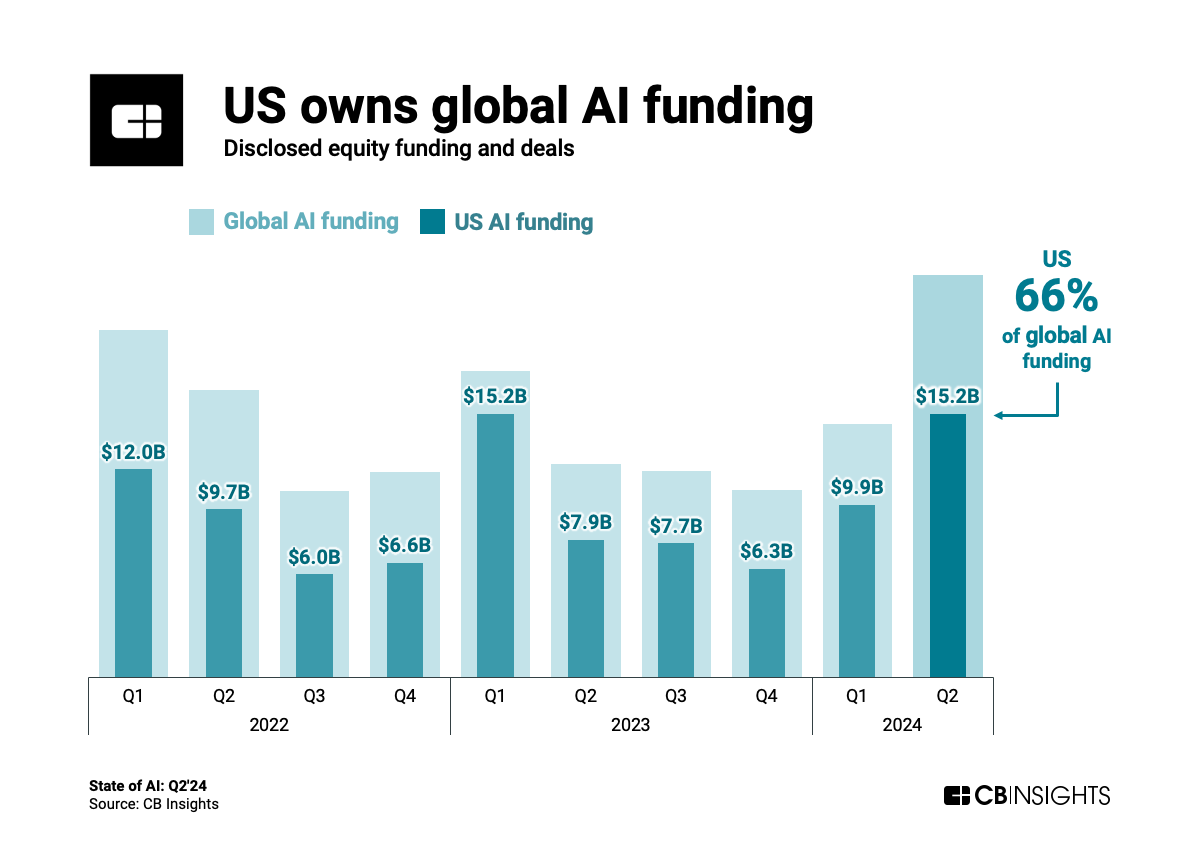

Chart(s) of the Week

The Links

Cato Institute globalization polling roundup: TND, AEI, CEI, WorldTradeLaw, NRO, Reason—twice (related)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.