My, what a year the last few weeks have been. With the Biden-Trump debate debacle, the Trump assassination attempt, the Vance Veep Victory, and now the Biden (and Harris) bombshell, one could be forgiven for spraining a thumb trying to doomscroll through the latest U.S. political news. It is intense—and, of course, could very well determine the future of the federal government.

Yet, despite what has inarguably been the most tumultuous and consequential few weeks in recent political memory, the response from financial markets and the vast majority of the non-political world has been … crickets.

A surprised Politico noted the situation last Friday:

The events of the last three weeks unleashed a tornado that could change Washington forever and upend political orthodoxies that have shaped economic policy for decades. Investors hate uncertainty. But even as questions swirl around President Joe Biden’s viability atop the Democratic ticket— and despite any fear of the possible damage that former President Donald Trump’s tariff and immigration policies could do to the U.S. economy—markets show no indication of concern. Even the shooting at Trump’s rally last weekend had little bearing.

And then followed up with some optimistic thoughts as to why:

That markets haven’t responded more aggressively to political turmoil could be interpreted as a sign of optimism that U.S. institutions are secure enough to withstand whatever tumult is inflicted by political leadership, said Alec Phillips, the chief U.S. political economist at Goldman Sachs. If investors thought the differences between a second Trump or Biden administration— or another Democratic alternative— were substantial enough to affect the rule of law, “markets might move when [election] probabilities change,” Phillips told MM. “Everyone wants to talk about what different outcomes mean,” he added. “But the whole point is we don’t really know.”

JPMorgan Chase CFO Jeremy Barnum said during a media call last week that the current environment is “no different” than any other, and that while “everyone’s talking about it … I don’t think that’s financially material in the context of earnings.”

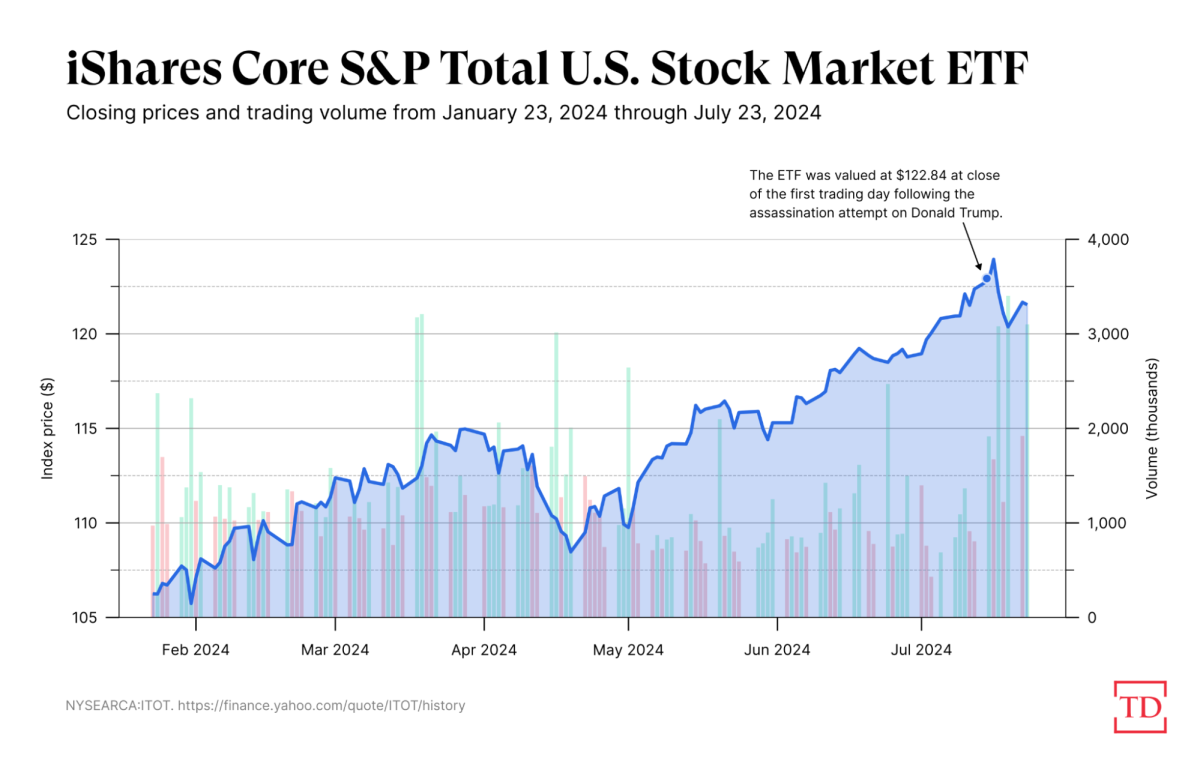

That relative market calm didn’t change on Monday following Biden’s historic Sunday announcement. Here, for example, is the S&P total market index, which covers thousands of publicly listed companies of all sizes across multiple U.S. stock exchanges:

Between the closing bell on June 27 (the date of the now-infamous presidential debate) and the close this Monday, the index is up a little more than 2 percent—part of a mostly steady climb dating back to late 2022. Other broad measures of U.S. financial markets show similar things.

Even indicators of stock market volatility haven’t really moved much over the last month of intense political turmoil. For example, the Chicago Board Options Exchange's Volatility Index (“VIX,” also known as the “fear index”), which distills the stock market's volatility expectations based on S&P 500 index options, has increased since late June and ticked up after the Trump assassination attempt, but it’s still nowhere near historical highs (dating back to 2004) and actually ticked down on Monday following the Biden news.

Instead, Bloomberg observed Monday morning, "The market reaction to Biden’s decision to quit the race and endorse Kamala Harris has so far been fairly muted, with the US dollar little changed and Treasuries marginally higher.” As one analyst put it in the article, “This political shake up shouldn’t materially alter the direction of the markets. … The ultimate direction of the S&P 500 will still be determined by economic growth.” Other stock-watchers agreed, with earnings and monetary policy far outweighing the presidential race. The fundamentals, in other words, still matter.

Outside of financial markets, meanwhile, regular folks—at least ones outside the Beltway (but I repeat myself!)—also seem to be fairly calm about it all. I was out shopping when the Biden news broke on Sunday and laughed to Mrs. Capitolism about how blissfully oblivious—or already over it—everyone at the outlet mall seemed to be. They were walking and talking and trying stuff on, with nary an overheard mention of Biden or Trump or Harris among them. My personal “My Sports” list on Twitter, meanwhile, was still (thankfully) focused on sports, with just a few random politics tweets thrown in. (Stay in your lane, sports people!) An old friend emailed me something similar after the Trump shooting—he was struck by how everyone around him ingested the news and, instead of taking up arms or building a bunker, just kept on with their daily lives—despite a major and inarguably upsetting (and possibly even incendiary) political event having taken place just a few hours earlier.

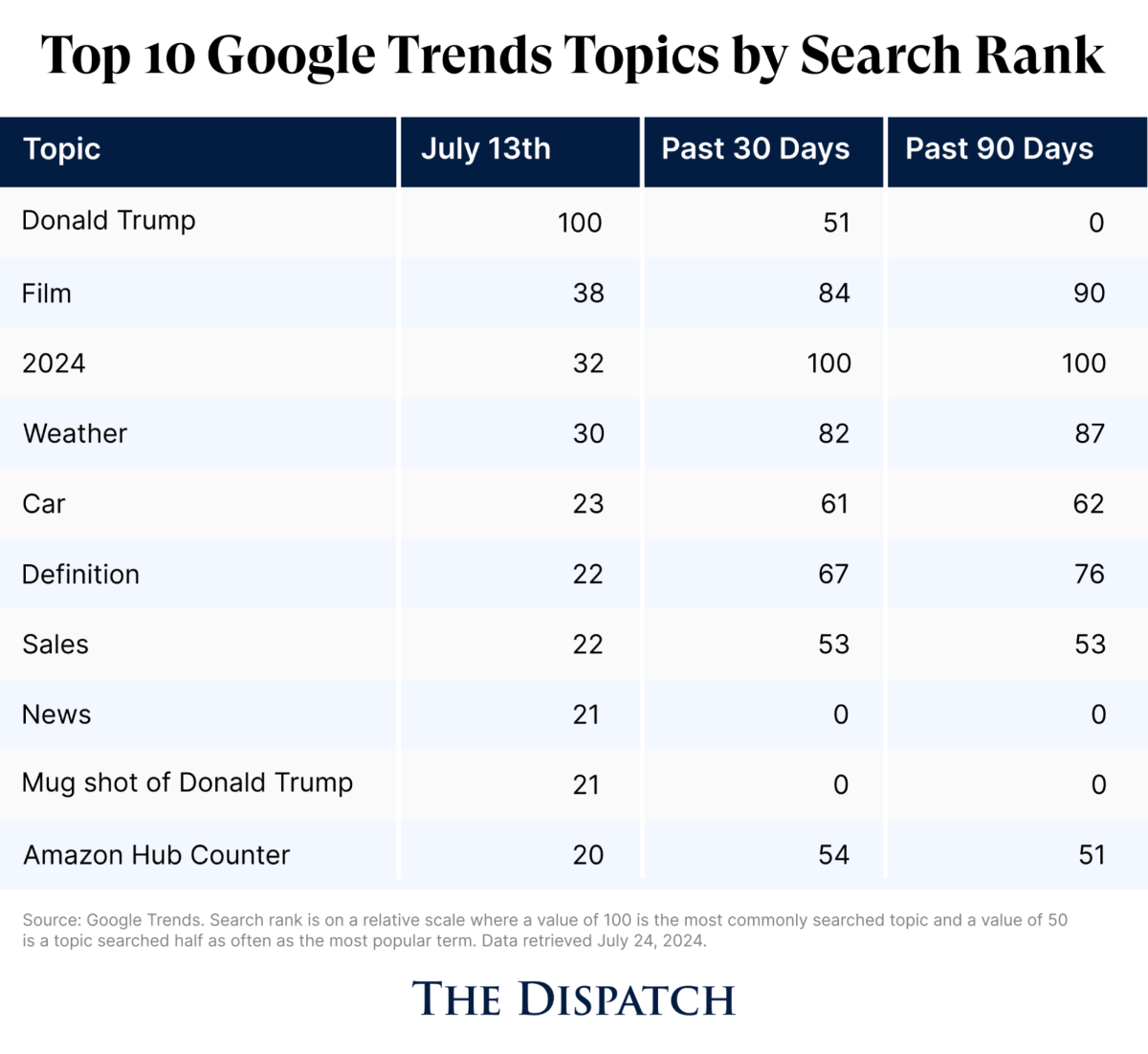

Google search data indicate that these aren’t just cherry-picked anecdotes. On July 13, for example, Trump understandably owned Google’s top search topic and search query. Between June 22 and July 22, however, he came in fifth—beaten by the weather, google, amazon, and youtube, and followed shortly thereafter by Biden and sports, cars, dogs (but not cats!), home depot, target, and other random life-staples that we search for daily. Back it out to the last 90 days, and neither Trump nor Biden crack the top 10. Other data points show people continuing to do what they do or even tuning politics out: Average MLB attendance is basically flat versus 2023; the presidential debate audience (51.3 millions households) was down significantly from 2020 (and more than double the audience of Biden’s big news conference two weeks ago).

Some Reasons for Optimism

These non-events don’t mean, of course, that politics and policy don’t matter—if they didn’t matter, I’d be wasting my life. And one can reasonably argue that Americans and financial markets should be paying more attention to this stuff.

Yet, overall, the calm over the last few weeks leaves me with mostly positive takeaways.

First, the federal government and the presidency are huge and powerful (too huge and too powerful), but they still don’t dictate the U.S. economy (no less the global economy) or our day-to-day lives. Policy can and does affect things on the margins, modestly bolstering or reducing economic growth along the way, and it can surely punish or reward certain companies and people. Gross clientelism and cronyism are, moreover, still gross, regardless of their macroeconomic effects. But in many ways, these are deck chairs on the cruise ship America (no, not the Titanic!), the general direction of which still depends on market, not political, fundamentals.

Surely, some of the broad movements in financial markets could reflect the fact that aggregate metrics like stock indices are hiding significant moves by big investors changing their portfolio mixes and strategies in response to presidential developments—moving in and out of certain stocks without the overall toplines changing much. True or not, however, this reinforces the notion that changes in the White House will affect certain industries and perhaps growth on the margins but—absent unexpected and radical changes that either haven’t been proposed or are highly unlikely—won’t alter the U.S. economy’s direction overall. That direction was and remains a product of bigger, private market forces and the billions of people that spontaneously and unknowingly drive them.

Two recent and related examples underscore this point:

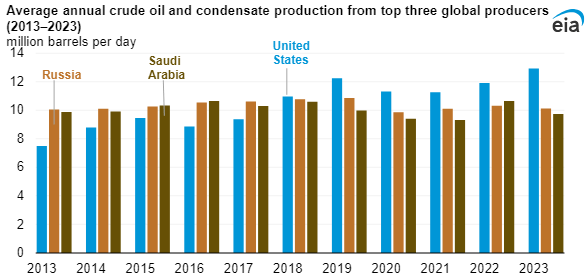

- For all the talk of the Biden administration’s “war” on oil and gas, the New York Times reports that the U.S. oil industry is “booming” and that U.S. producers are enjoying “record profits” and are “flush with cash”—thanks “largely to market forces” (mainly global demand) and despite policies here and abroad intended to boost energy alternatives and discourage fossil fuel production and consumption. Earlier this year, in fact, the U.S. Energy Information Administration reported that the “United States produces more crude oil than any country, ever” and has held the global crude oil production lead for six years in a row, across both the Trump and Biden presidencies:

- On the flip side, the head of the nation’s largest EV charging network just publicly shrugged off a possible Trump presidency and the resulting termination of U.S. EV subsidies because, he asserted, global producers and consumers will continue to shift toward EVs. As he put it to Bloomberg, “the overall market forces are a much stronger force than whatever the government can do to accelerate or not accelerate EV adoption." He’s convinced those market forces will mean widespread commercial and retail EV use in the United States (and success for his company), and maybe he’s right. But being right or wrong isn’t the point. The point is that it’s the market—not the president or some subsidy scheme—making the ultimate call. (For what it’s worth, I agree.)

For all our (very real) concerns about past, current, and possibly future government interventions in the U.S. economy, the continued dominance of markets over the resident of the White House is undoubtedly a good thing. Maybe that changes in the future, but we’re not there yet.

Second, the nation’s collective shrug at recent political news once again shows why the common populist quip that “markets” are simply a “tool” to be manipulated and molded by government policymakers rings so hollow. “The market” isn’t a thing, like some blender that presidents can turn on or off or change speeds at will. It’s millions of people constantly acting individually or in a group—as consumers, producers, workers, managers, and so on—in pursuit of their own interests (whatever they may be) and informed by the price system. As Nobel laureate F.A. Hayek said in The Fatal Conceit, it’s from these spontaneous, uncoordinated interactions—not the government’s economic plans—that we create wealth:

The creation of wealth is not simply a physical process and cannot be explained by a chain of cause and effect. It is determined not by objective physical facts known to any one mind but by the separate, differing, information of millions, which is precipitated in prices that serve to guide further decisions.

Markets thus exist regardless of what policy is or what policymakers do, and they’re surely not some “tool” of the government or a handful of “elites.” And this is true whether you’re talking about oil or EVs or baseball or drugs or housing or, as National Review’s Dominic Pino reminded us last year, Thanksgiving turkeys:

How many turkeys are needed for Thanksgiving? Nobody knows, and nobody has to know. The planning process for Thanksgiving turkeys is decentralized through markets. Millions of people at various points in the process plan small things that are within their power to control, and with the aid of the price system, people get the turkeys they want.

This reality has important implications. As some guy named Jonah once said in another publication, for example, market participants (aka people) have rights that just can’t simply be disregarded because some politician doesn’t like how they’re acting (“just because the free market looks like a ‘tool’ from the vantage point of some policymakers and other elites gazing at society from olympian heights doesn’t mean my right to buy and sell what I want isn’t a right too.”). It also means that people (aka market participants) will act and react according to their own interests, regardless of what government wants or even tells them to do—absent extreme force that’s (thankfully) still generally rare in this country.

To paraphrase Jeff Goldblum, the market … uh … finds a way.

Third, the U.S. economy’s calm and resilience strongly cautions against politics-related hysteria, for both practical and strategic reasons. Yes, of course, we have real reasons to worry about (and try to address) the debt or taxes/tariffs or overregulation or gerontocracy or creeping statism and authoritarianism, and we should care about boosting economic growth at the margins (little changes add up!). But we must always remember that the U.S. economy is a huge and dynamic thing—comprising hundreds of millions or people, buttressed by centuries of law, and deeply intertwined with an even huger (and almost-as-dynamic) global economy. It takes a lot of terrible policy to cause big problems, and there’s a cost to crying wolf all the time about every discrete policy change. When Trump imposed his tariffs, for example, a few commentators warned of economic apocalypse and got lots of headlines trumpeting those claims. The rest of us—knowing the actual amount of imports involved and trade’s relatively small share of the U.S. economy—took a more measured approach: They’d be a small drag on growth and employment, bad for geopolitics, and especially painful for certain (blameless) American companies and workers. But they wouldn’t be apocalyptic, and studies now show that we were basically right. But can you guess which predictions today’s tariff-defenders always trot out to show that, when it comes to Trump’s even bigger future tariffs, the “elites” don’t know what they’re talking about?

Exactly.

Bad policy and bad government actors can hurt the U.S. economy, but they very likely can’t kill it—and we should always remember and be thankful for that, while also always striving for better. Maybe we really are hitting a “late communist Russia” tipping point, but “Mr. Market” and most Americans sure don’t think so, and—as we’ll discuss next week—I generally think they’re right.

Now, if you’ll excuse me I have a baseball game to watch.

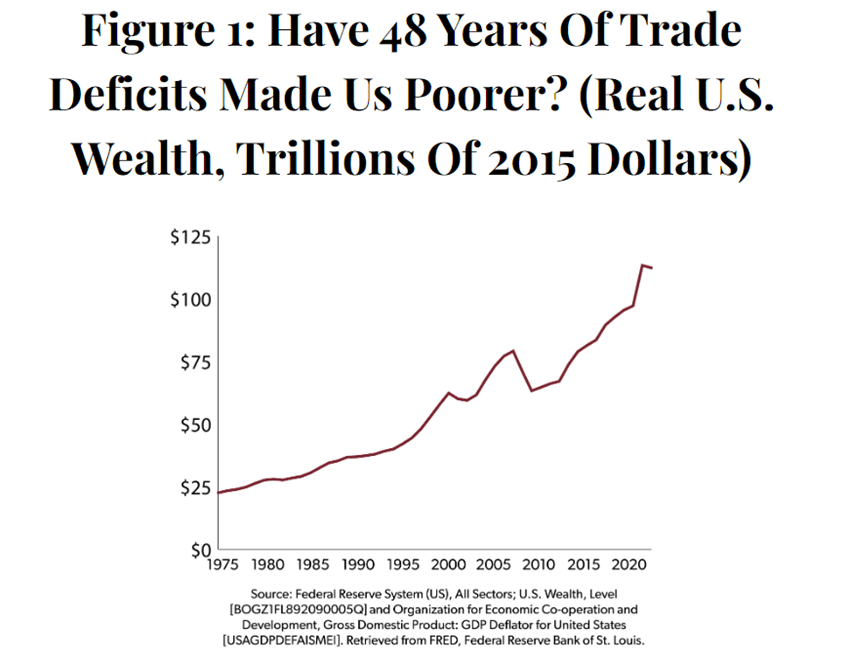

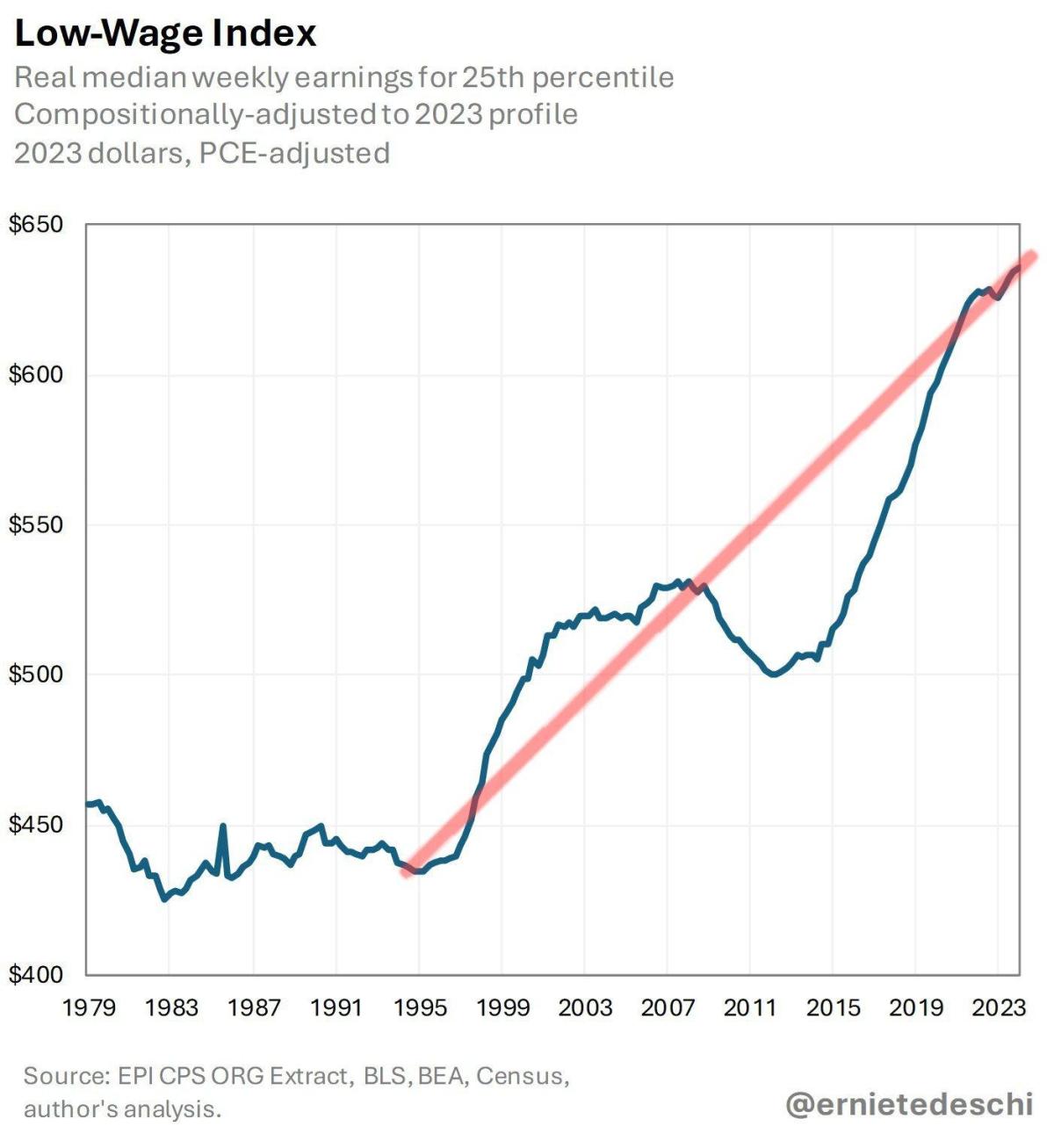

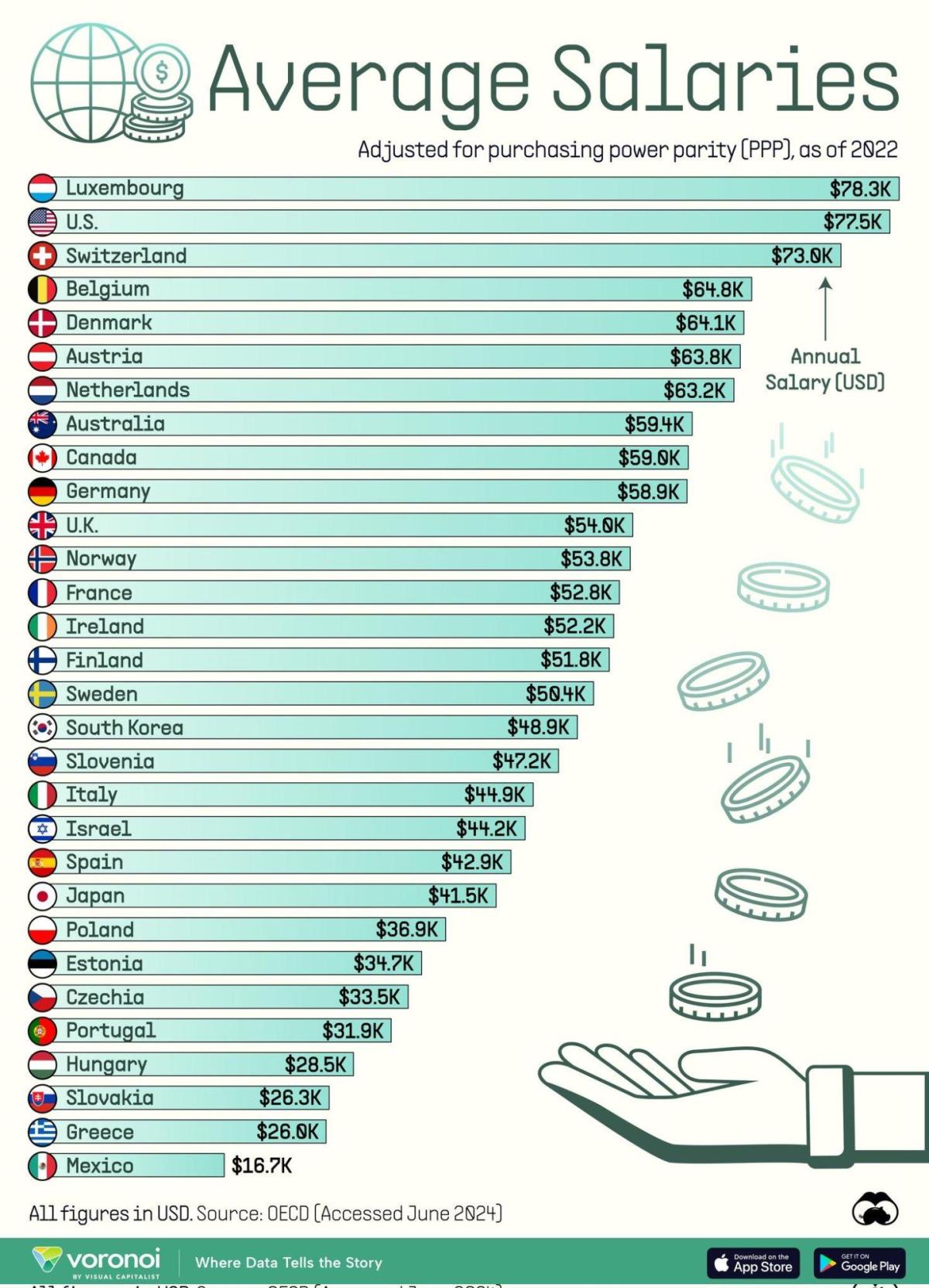

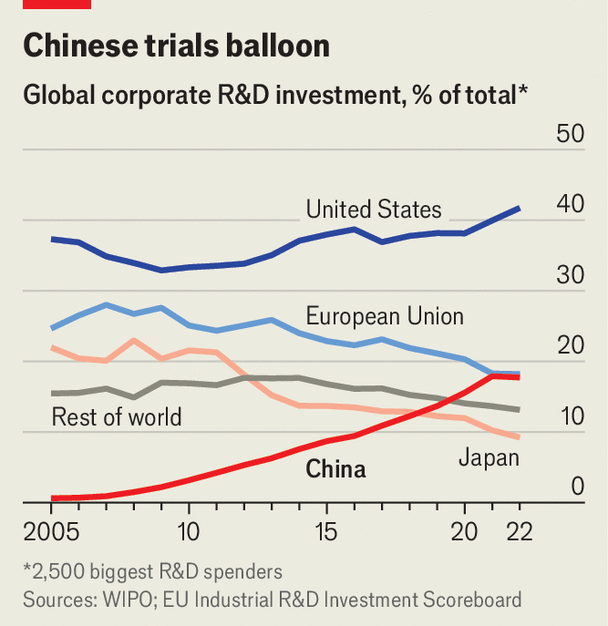

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.