Among the few constants in Washington is elected officials’ stubborn insistence on tying anything, no matter how mundane, to jobs. Fund a highway or a fighter jet: JOBS. Open a post office: JOBS. Ban self-checkout lanes: JOBS. Seizing on this obsession, many outside of the government routinely calculate, with often-absurd precision and methodologies, how many jobs a federal policy will supposedly create or destroy—numbers a politician will gleefully employ, regardless of the merits. And if you ever worked on a political campaign, you know from personal experience that proposed policy positions should—nay, must—come with a job number attached. (Boy, could I tell you some stories.)

Legitimate economists often bristle at this kind of talk for good reasons. Discrete job calculations in a massive, dynamic U.S. economy are notoriously tricky and depend on all sorts of variables, many of which are disconnected from the policy or project at issue. Furthermore, many policies don’t increase or decrease jobs but instead change the types of jobs we have. Most fundamentally, economists know that labor is a finite resource, and so jobs are considered part of a project’s cost, not one of its benefits. If the government could magically develop and install a cross-country hyperloop (or whatever) without using any time, materials, taxpayer dollars, or workers, it’d be a massive win: Not only do we get the hyperloop (or whatever), but all the resources the project would have used could instead be deployed elsewhere in the economy, boosting overall output and growth.

Still, in the wake of the Great Recession—when unemployment and worker anxiety were high, job openings low, wages stagnant, and the labor market’s future uncertain—a political obsession with job creation was at least understandable to even the most curmudgeonly of economists. Yes, of course, jobs are technically a cost and all those numbers are silly, but, with millions out of work and businesses not hiring, one could be (mostly) forgiven for pandering to voters about the bajillions of “shovel-ready” jobs a government project supposedly “saved or created.”

Today, however, this kind of talk is ridiculous. By all sorts of metrics, the typical American worker is doing well and is happy with the U.S. labor market. Given demographic changes (e.g., an aging population), moreover, the labor market remains tight. Things certainly aren’t perfect for all U.S. workers, but—even with inflation and the pandemic and other issues—most have it pretty good. Yet, if you were to listen to our political class and many wonks, you’d think that it was still 2014, that most American workers have seen little progress (if not outright regression), and that their future is bleak.

That’s mostly wrong, and the disconnect between their rhetoric and our reality says a lot about not only government policy but also about many of the people seeking to dictate it.

Charting the U.S. Labor Market’s Progress

The labor market’s radical shift from the pessimistic 2010s isn’t exactly breaking news. As you may recall, its steady improvement since the Great Recession was a prominent theme in my 2023 book, Empowering the New American Worker, and something we’ve discussed repeatedly here at Capitolism. As George Mason University’s Don Boudreaux noted last week, several others have been beating this drum too.

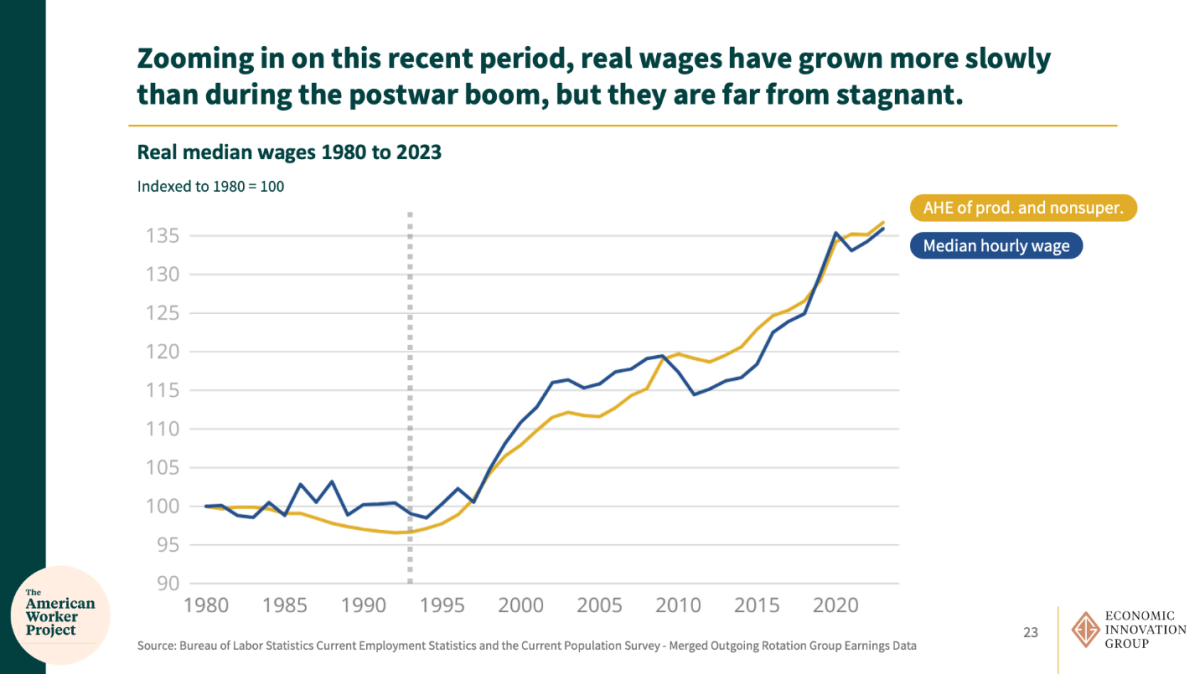

A brand new report from the Economic Innovation Group adds to the growing consensus. Most notably, the folks at EIG again confirm that inflation-adjusted pay for the typical American has been on a solid run since the mid-1990s, powering through multiple recessions in the process:

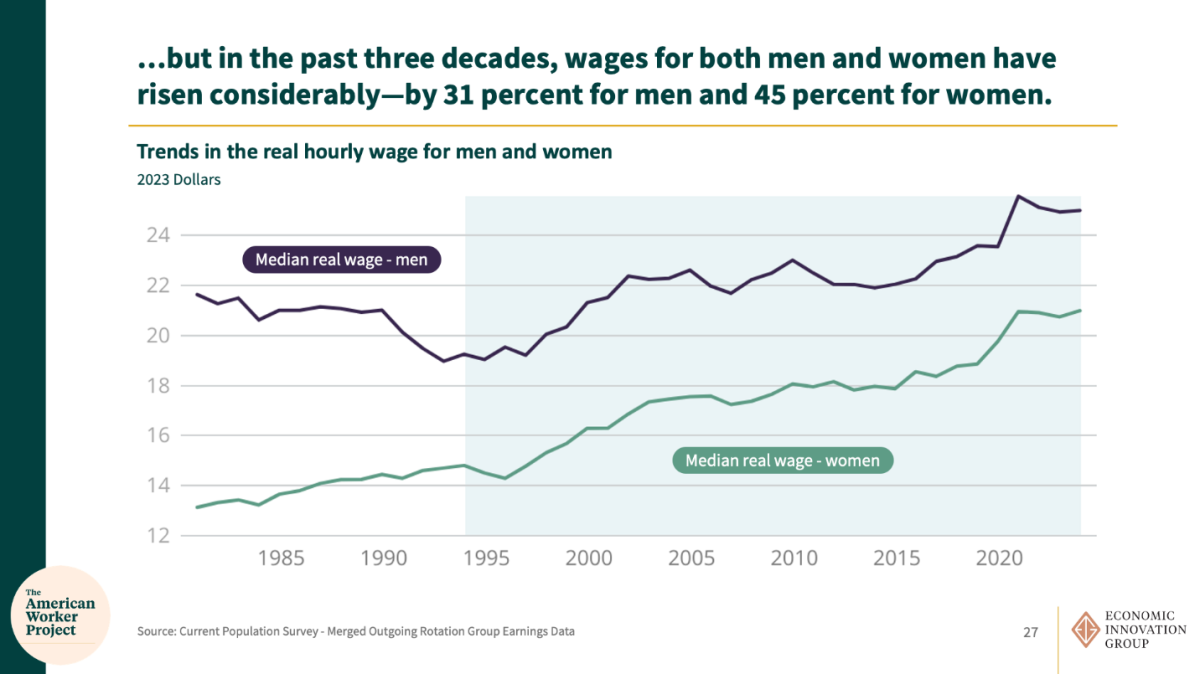

They further show that both women and men have enjoyed these wage gains …

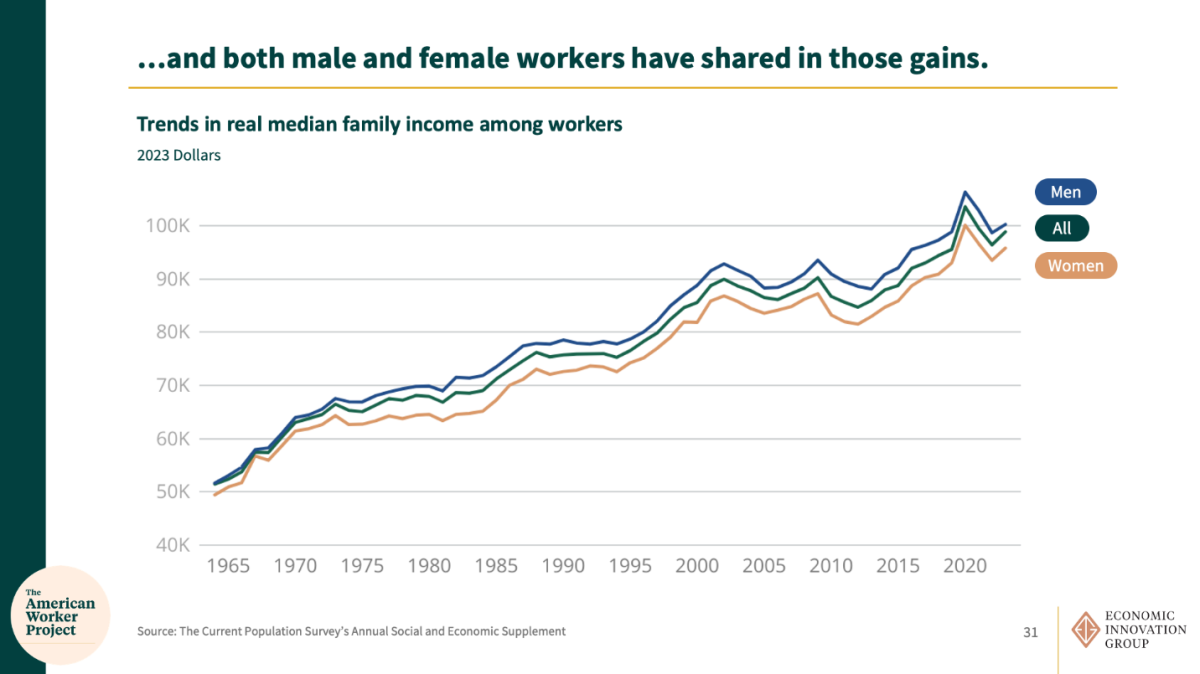

… and that the typical American family has also done well:

EIG’s findings thus confirm previous analyses showing substantial, long-term wage gains for all American workers—especially those on the lower end of the income spectrum.

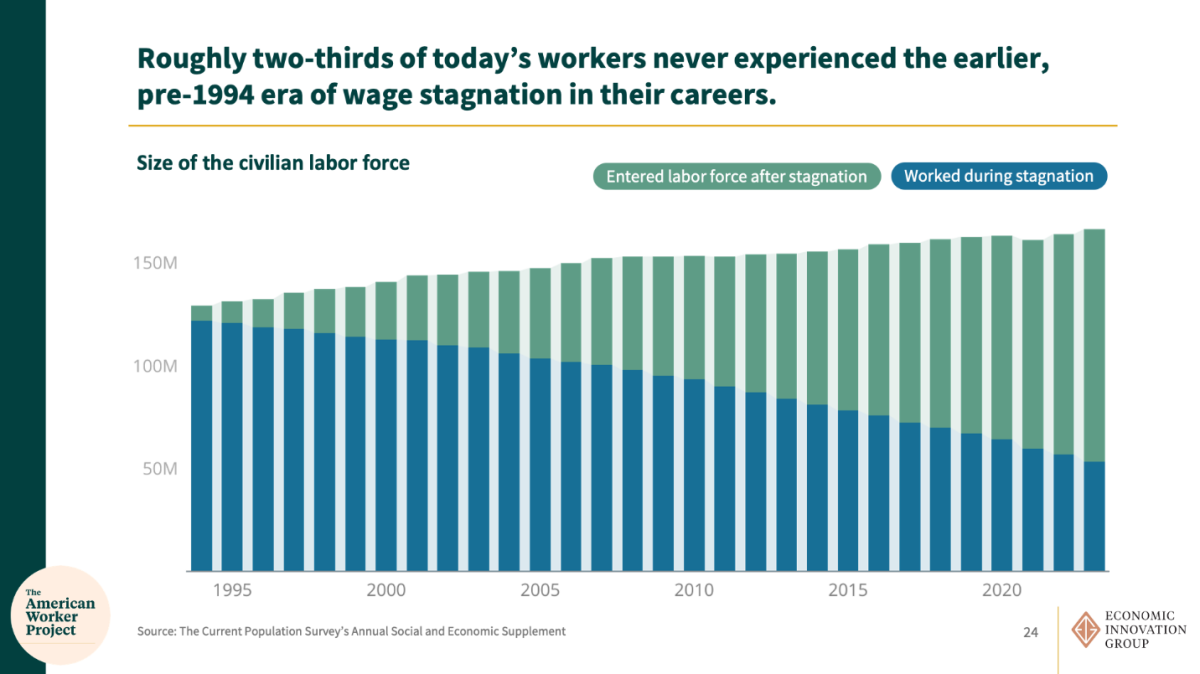

The EIG report also looks at how American workers feel about their jobs and their place in today’s U.S. labor market. For starters, they show that most of today’s workers never actually lived through the last prolonged period of real wage stagnation in the 1980s:

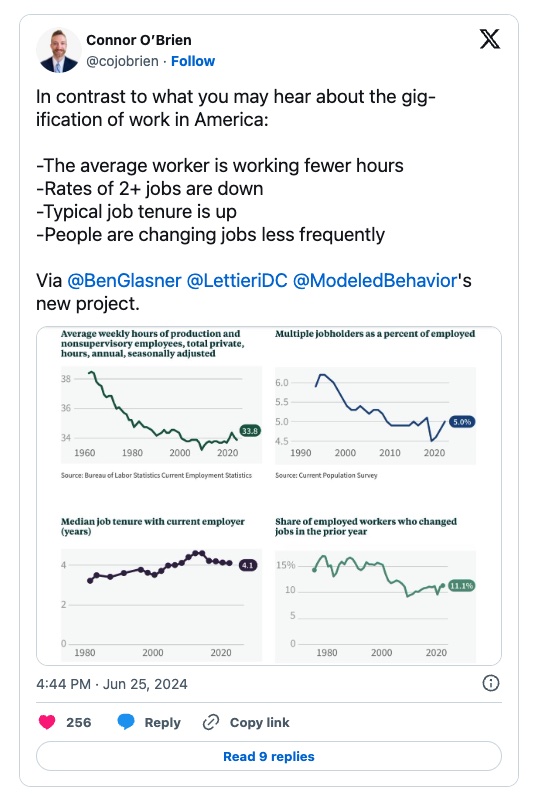

And, as EIG’s Connor O’Brien notes, the report contradicts the continued populist narrative that most American workers are insecure and slaving away in low-paid “gig” jobs:

Along similar lines, the EIG data show that, unlike in the early 2010s, only a tiny share of Americans are working part-time because they can’t find full-time work, and that almost 90 percent of workers are “completely or somewhat satisfied” with their job security. American workers also are more educated and have more paid vacation time, while around 80 percent of us get paid sick leave. A record number of workers (though still just 27 percent) also have access to paid family leave. Our workplaces are much safer, too.

Overall, the EIG data portray a U.S. labor market with a few discrete areas of continued need, but doing well overall, especially compared to what many of us experienced for much of the last decade and what we’re still hearing today from populist politicians and wonks about the entire economy. As AEI’s Michael Strain noted in a supportive essay responding to EIG’s report, the populists’ gripes were (somewhat) understandable a decade ago:

The real median wage fell following the onset of the financial crisis, and did not recover its 2007 level until 2014. In other words, had the expansion ended in 2014, real wages at the median would not have recovered despite five years of economic growth. Indeed, the severity of the downturn and the slow recovery not only help to explain pessimism about the state of American workers—they help to explain the rise of populist politics in both U.S. political parties (and throughout Europe).

After more than a decade of growth, however, the pessimistic view of the typical American worker as desperate and insecure and, of course, in need of federal government protection from cradle to grave lacks credibility. Few are miserable, and we haven’t seen real, long-term stagnation since the 1990s.

Indeed, as we briefly discussed more than a year ago, the bigger long-term concern about the U.S. labor market is sufficient labor supply and persistent labor market tightness, not insufficient labor demand and slack (and thus stagnation). Even after months of higher interest rates, the expiration of most pandemic-related subsidies, a surge of foreign workers, and other important events here and abroad, the new concerns remain (though they’re certainly more subdued than they were two years ago). Today, the unemployment rate is still historically low, job openings and prime-age employment rates are still historically high, businesses are still reporting difficulties finding workers, and economists are still worrying about prices and wage growth being too hot, not too cold.

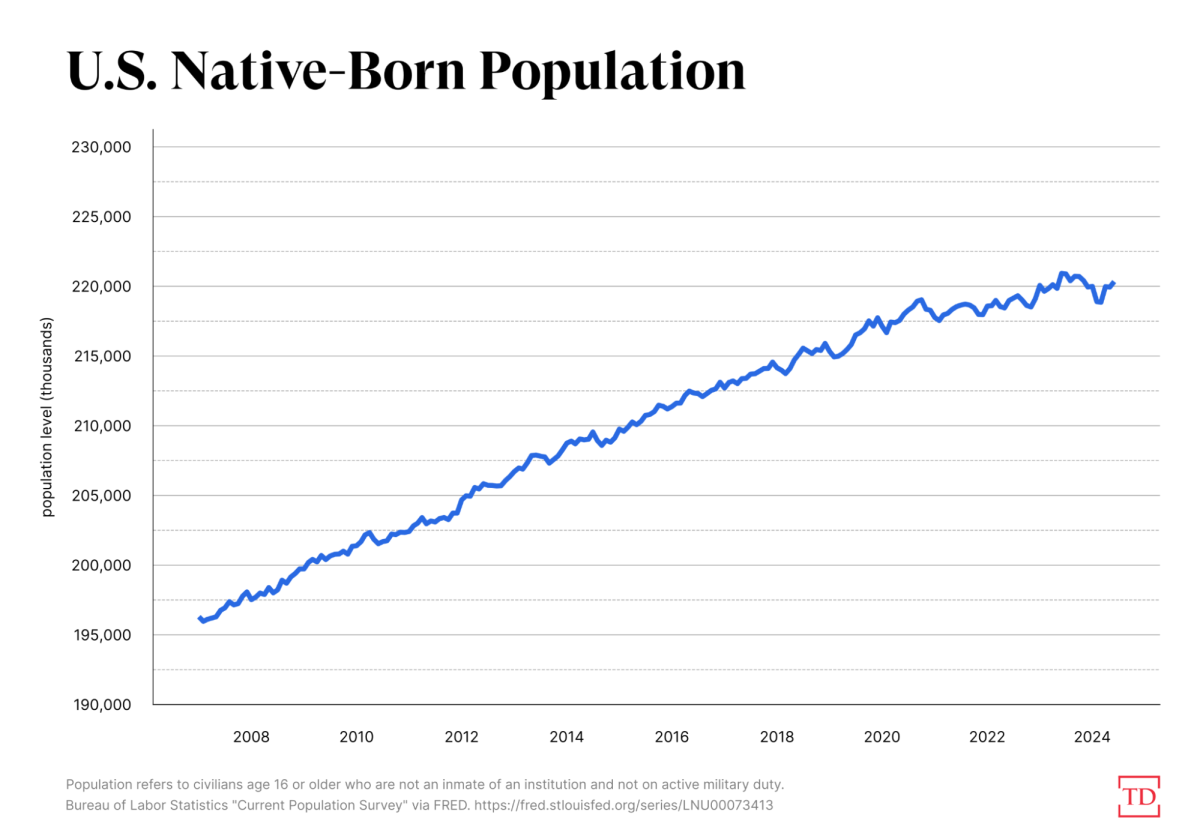

Things might soften further in the short term, of course, but demographics and the pandemic have all but ensured that the base case (i.e., without major policy reforms) for the future U.S. labor market is one of tightness, not slack. Thanks to decades of falling birthrates and restricted immigration plus continued aging of the baby boomer generation, the native-born U.S. population has barely budged since 2020 after decades of steady growth:

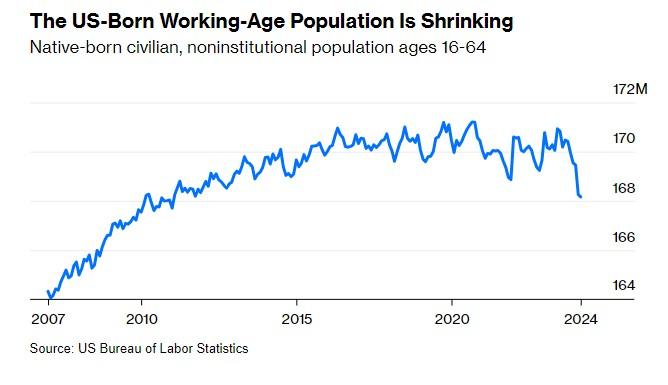

Matters are even worse when looking at just working-age Americans. The “prime age” (25-54) native-born population has been basically flat since 2013:

And now the broader number of “working age” native-born Americans has started to fall:

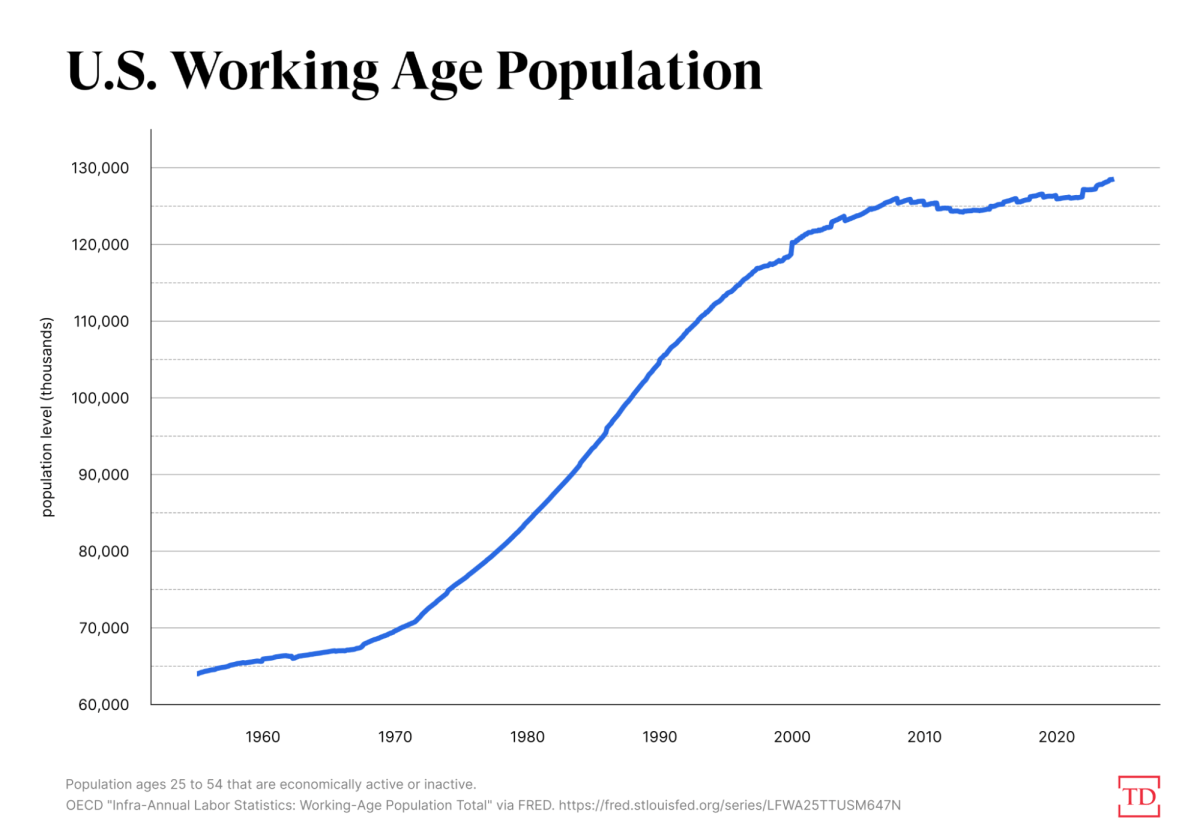

Even the total working-age population—natives and immigrants—flattened out around 2007:

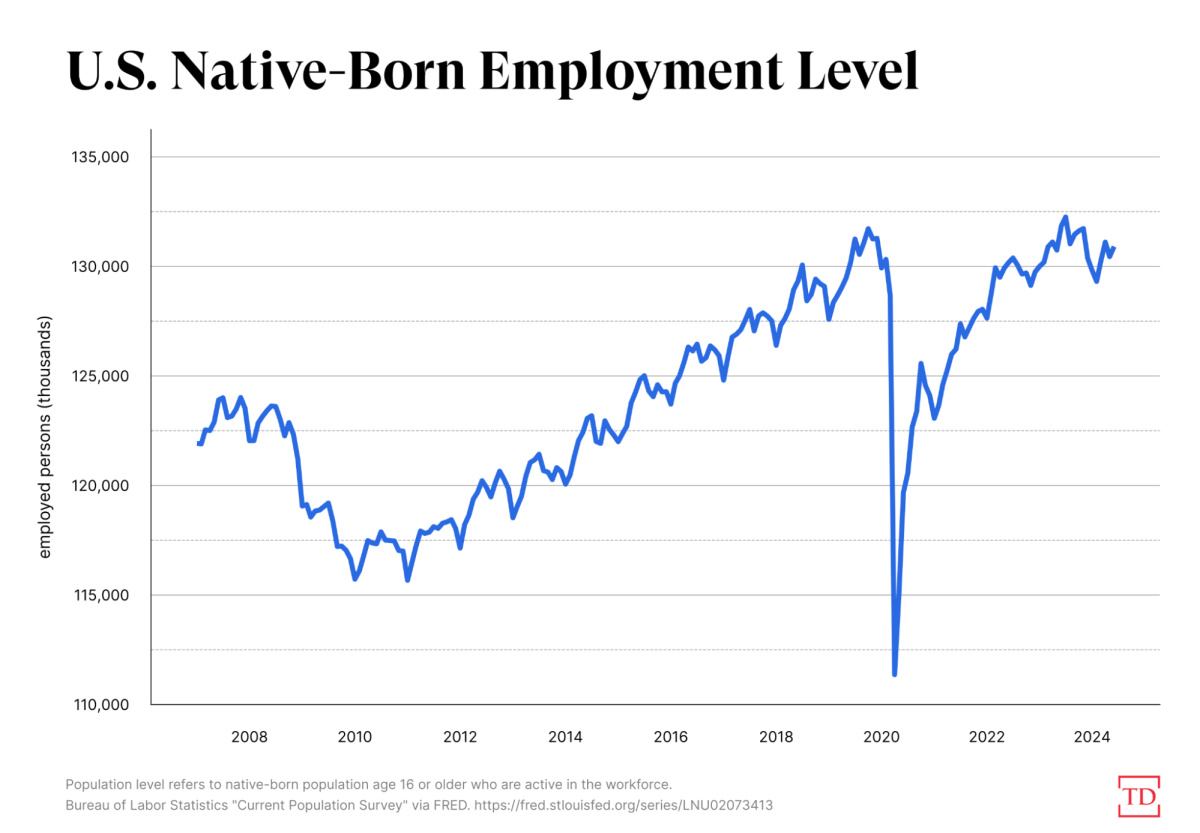

In terms of actual workers (i.e., not just warm bodies located in the country), the story is similar: Even with prime-age, native-born Americans working at high rates not seen since the 1990s, the total number of native-born workers employed today has similarly flatlined after years of steady growth before the pandemic:

We should expect outright declines in the years ahead because the U.S. workforce is getting older for the aforementioned reasons. As the EIG report notes, the median American worker was 34 in 1980 but is 41 today, and the share of seniors working has almost doubled since 1990:

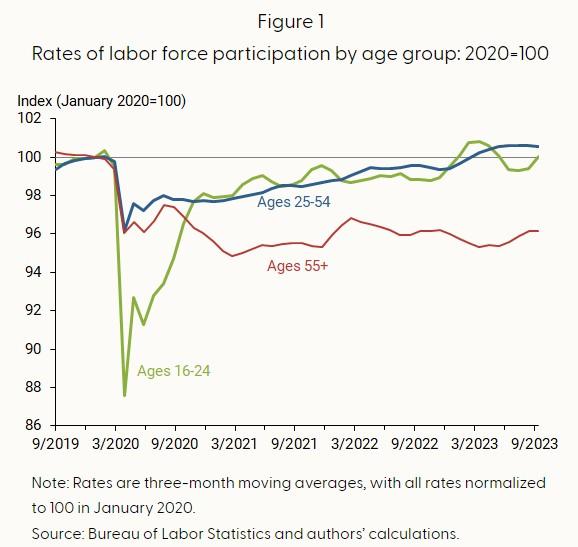

The pandemic accelerated the labor market effects of an aging U.S. population in two ways. First, many older American workers got really sick or even died, with sad and obvious implications for the economy. Second, many older workers retired early and, as shown in a March 2024 report from the San Francisco Fed, have never come back (red line below):

“Despite the strongest labor market in decades,” the authors conclude, many older early-retirees appear to have decided they’re just not returning to work, leaving the U.S. economy with “an estimated shortfall of nearly 2 million workers.” That’s sure to leave a mark.

Policy for Our New Normal

Put it all together and you have a labor market that, even with a major recent influx of new foreign workers and months of tepid economic growth, remains tight and will most likely continue to be tight in the future. (The San Francisco Fed just calculated that the U.S. labor market’s long-run growth trajectory is mostly unchanged from projections made before the recent surge in immigration.) News stories today thus detail how U.S. industries and regions are planning to cope with our new, demographic-fueled labor market normal—deploying more robots, recruiting workers from the Sun Belt or Puerto Rico, and so on. How these efforts shake out will be one of the economic stories of the 2020s.

Economists, meanwhile, are grappling with the broader policy implications of a tight U.S. labor market and possible reforms. As EIG’s Adam Ozimek wrote in January and recently expanded upon in a podcast over at The Atlantic, policymakers today shouldn’t be cheering demographic-driven labor market tightness or pursuing economic policies to make it even tighter. Instead, they should be worrying about the aging population, its potential long-term harms to the U.S. economy, and how to ameliorate them. (See this Capitolism for more.) If not, the country could suffer from not just some unfilled jobs (and bad service) at local watering holes, but also a shrinking tax base, slower productivity (and thus wage gains), less entrepreneurship and innovation, and lower economic growth. Here’s how he put it in the podcast:

When you have new people coming in, you’re getting more new businesses, right? Because you both have more new entrepreneurs, and because you have a growing labor force. And businesses start to take advantage of that. You have more innovation, right? Because the population is growing bigger. You have a greater number of innovators there, and innovators create lots of spillovers.…

And I can tell you this—but this is both empirically very well founded, in the sense that there’s a variety of well-done studies showing it—and I can just tell you, personally, as someone who is an entrepreneur, if you are in a place where the population growth is falling so that every year there’s fewer workers and every year there’s fewer customers, that’s not a great place to start a business, right? It’s very zero-sum.

If you’re in a place where population is growing, so that next year there’ll be more workers to hire, so that next year there’ll be more customers to serve, and you can look to the future, No, look, I can make this investment. I can expand, that’s just a better environment for entrepreneurship. It’s a better environment for innovation, fast-growing startups—things like that.

To counter these issues, Ozimek points to two policy areas that I also noted last year—one hard and one easy. The hard one is to improve the U.S. birth rate, as policy fixes have proven both expensive and uncertain. The easier one (policy-wise, not politically) is expanded immigration, especially on the high-skill end: “If we let those people in, it’s not only going to help offset the declining population, but it’ll help offset the negative impacts of the declining population on productivity, growth, and innovation.” A recent Dallas Fed report concurs with Ozimek’s conclusions, with an ominous warning about a future U.S. economy without more foreign workers:

If immigration normalizes, it will return to rates that are insufficient to sustain the type of economic growth the U.S. is accustomed to. The nation is in a sort of demographic autumn, and winter is coming. The retirement of the baby boomers and overall aging of the workforce, as well as low and falling birth rates mean population growth will become entirely dependent on immigration by 2040, as deaths of U.S.-born will outpace births. Because economic growth depends on labor, capital and productivity, growth in these factors will set the speed limit of the economy. While technological advances and incentives for investment will contribute to productivity growth, immigration will be vital to propping up labor force growth.

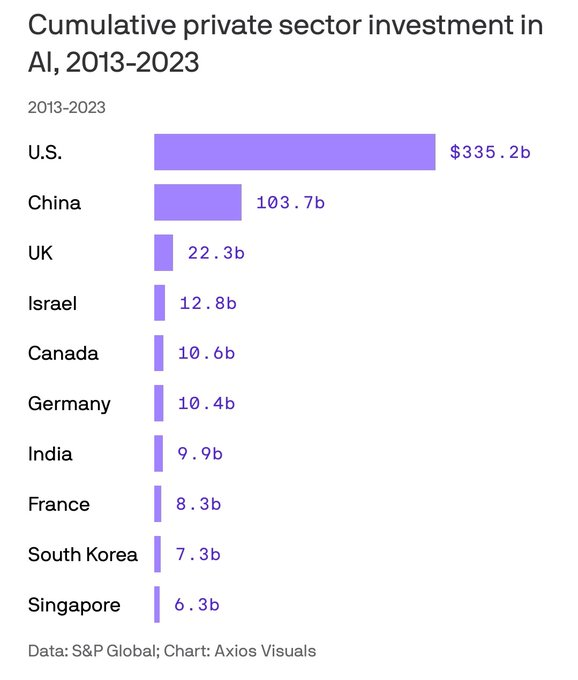

There are certainly other policies that federal, state, and local governments should pursue to boost productivity, innovation, and growth, and help American workers navigate our new economic normal. (My book—plug!—had dozens of ideas.) Innovations like AI, robotics, and human longevity might also mitigate some of the population-related problems that Ozimek and others foresee.

Summing It All Up

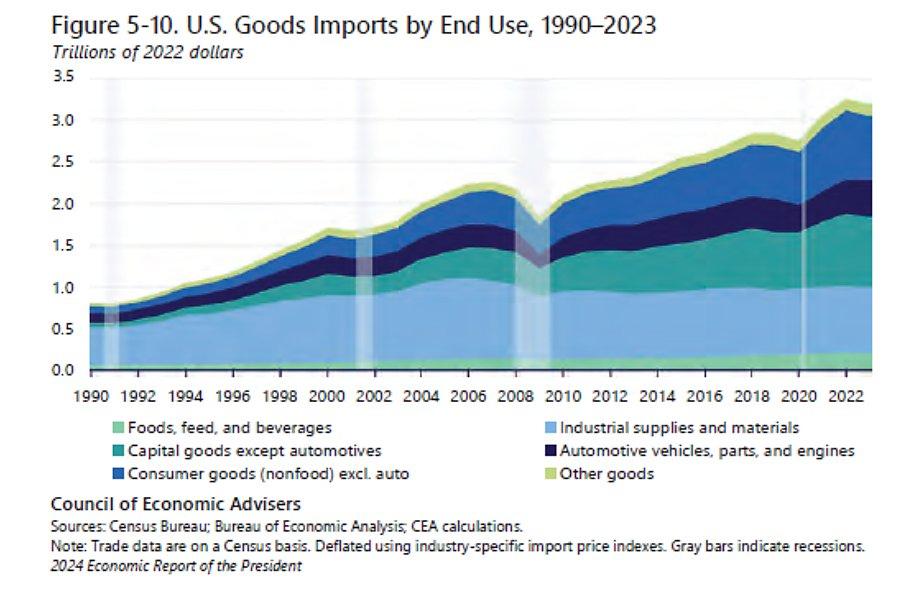

The labor market certainly isn’t the only policy area in which the Beltway conventional wisdom remains a decade or more behind the current economic reality. Off the top of my head, there’s China, government spending and debt, and—as EIG details in another new report (and as we’ve also recently discussed) —the American localities that our modern, global economy has supposedly “left behind.” In these and other cases, politicians and wonks—indeed, even entire think tanks—developed their proposals, rhetoric, and identities during the old normal and just never updated them to address the new one. As they continue to push policies seeking to ameliorate past economic problems, current politics and policy suffer as a result—as does the current economy. (Here’s a recent example.)

As our depressing presidential race makes clear, American politicians are old and scripted and transactional, so we probably shouldn’t expect them to quickly update their policy worldviews in the face of new information (that they might not even read!). Government is also notoriously slow to adjust, and, given the highly visible and personal nature of employment, an indiscriminate political obsession with JOBS will probably never go away fully.

The wonks, on the other hand, have no such excuses. It’s their job to stay abreast of the latest data and, where needed, to revise their rhetoric, policy, and outlook in the face of new information. Today, that means less talk about federal jobs programs or ameliorating a “national epidemic” of wage stagnation and worker insecurity, and more talk about lowering prices and boosting educational outcomes, global competitiveness, mobility, productivity, and, yes, labor supply. It could also mean targeting the relatively small number of American workers who truly are still struggling today, instead of proposing costly, Rube-Goldbergian schemes to freeze the U.S. economy in amber and supposedly protect all American workers from global perils that just don’t really exist. After all, the dynamic U.S. labor market—for all its continued warts—remains the envy of the industrialized world. Let’s not screw that up, okay?

We can’t predict the future of the American worker, but the outlook today is surely different from what it was a decade ago. Those still playing from the 2014 playbook either don’t know that things have changed, or they simply don’t care.

Chart(s) of the Week

The Links

New Cato Defending Globalization essays: Globalization doesn’t mean global government (by Ilya Somin) and why the first globalization era was delayed by a century (by Vincent Geloso)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.