Dear Capitolisters,

With Labor Day right around the corner, the next few days are bound to feature even more political rhetoric about the “American worker.” I say “even more” here intentionally, as U.S. politicians have hyped “pro-worker” policies since at least the 2016 presidential election cycle. President Trump, for example, had a 2020 “Pledge to America’s Workers” that heralded past executive actions supposedly helping American workers, and President Biden has embraced similar rhetoric and policies (e.g., his “worker centric” trade policy and recent infrastructure, energy, and semiconductor laws that, he says, create jobs for American workers). And it seems like everywhere you go in Washington these days, you find some aspiring politician, bureaucrat, or wonk lamenting the supposed plight of today’s American worker and—of course—promising to fix it.

Just How Bad Do Workers Have It?

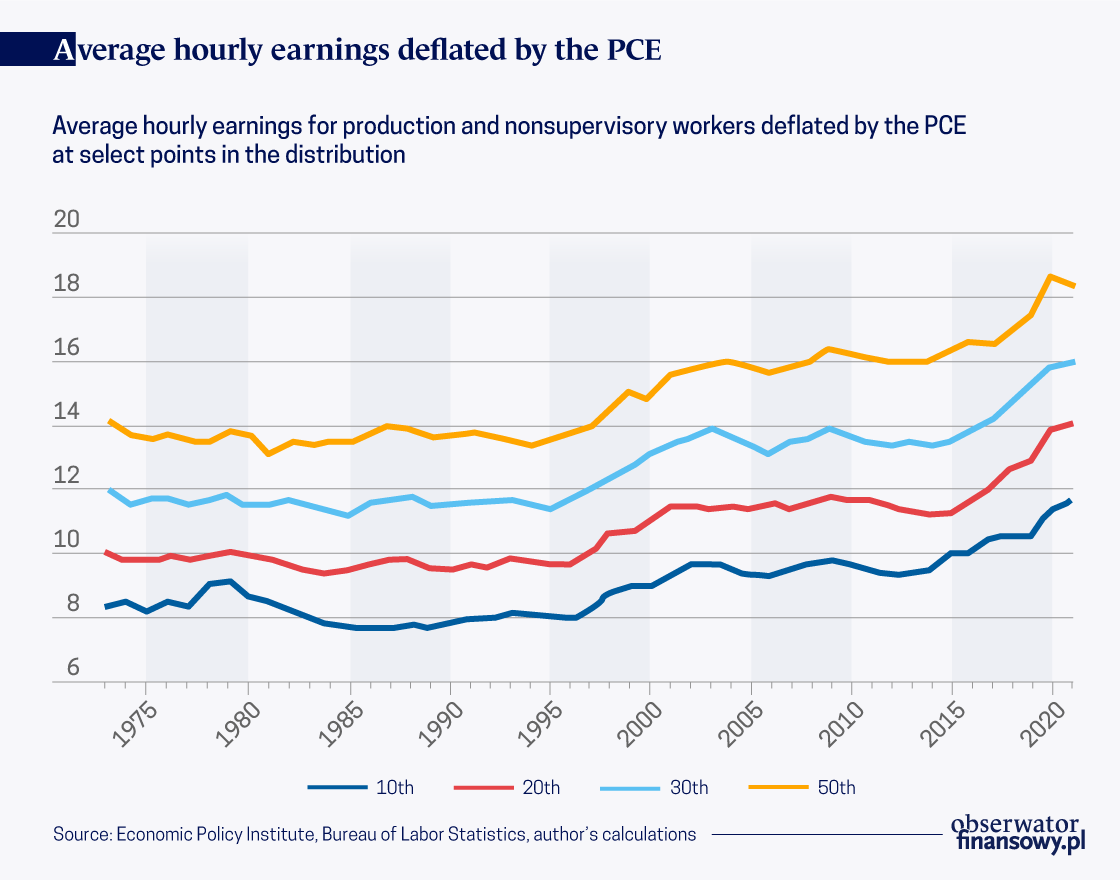

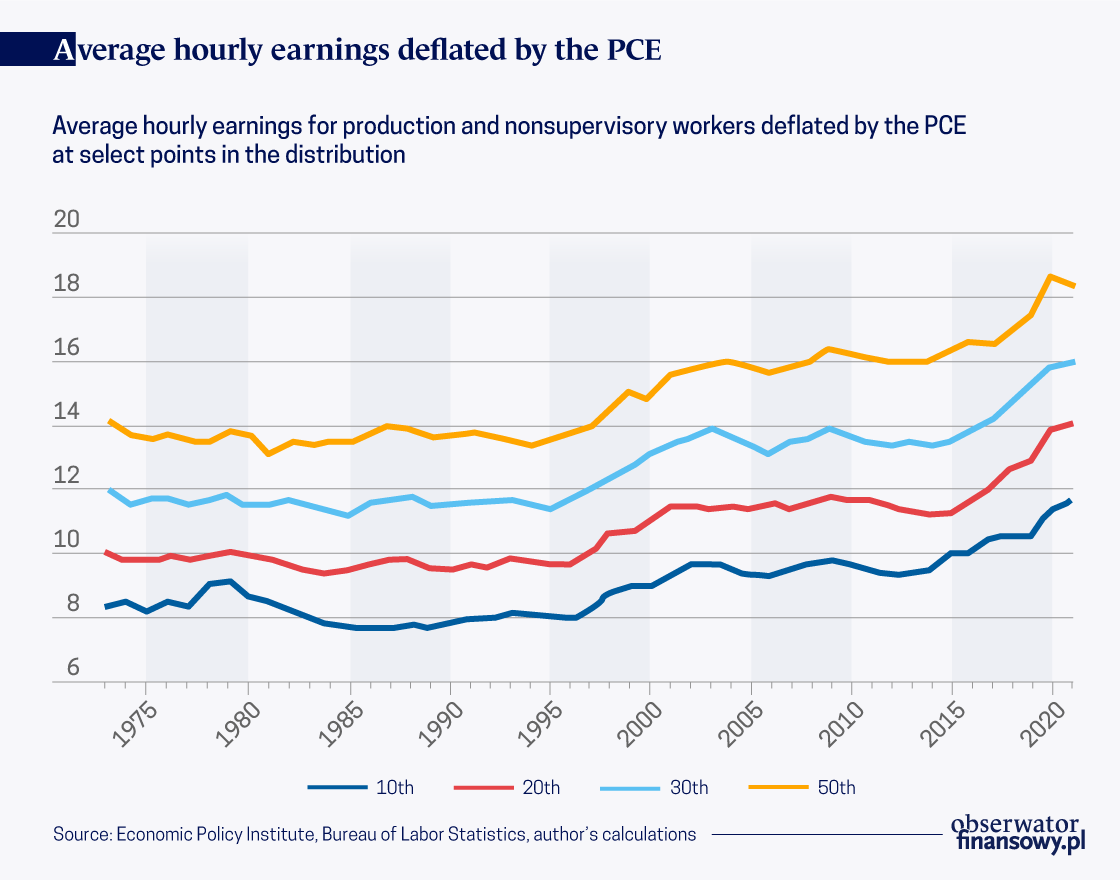

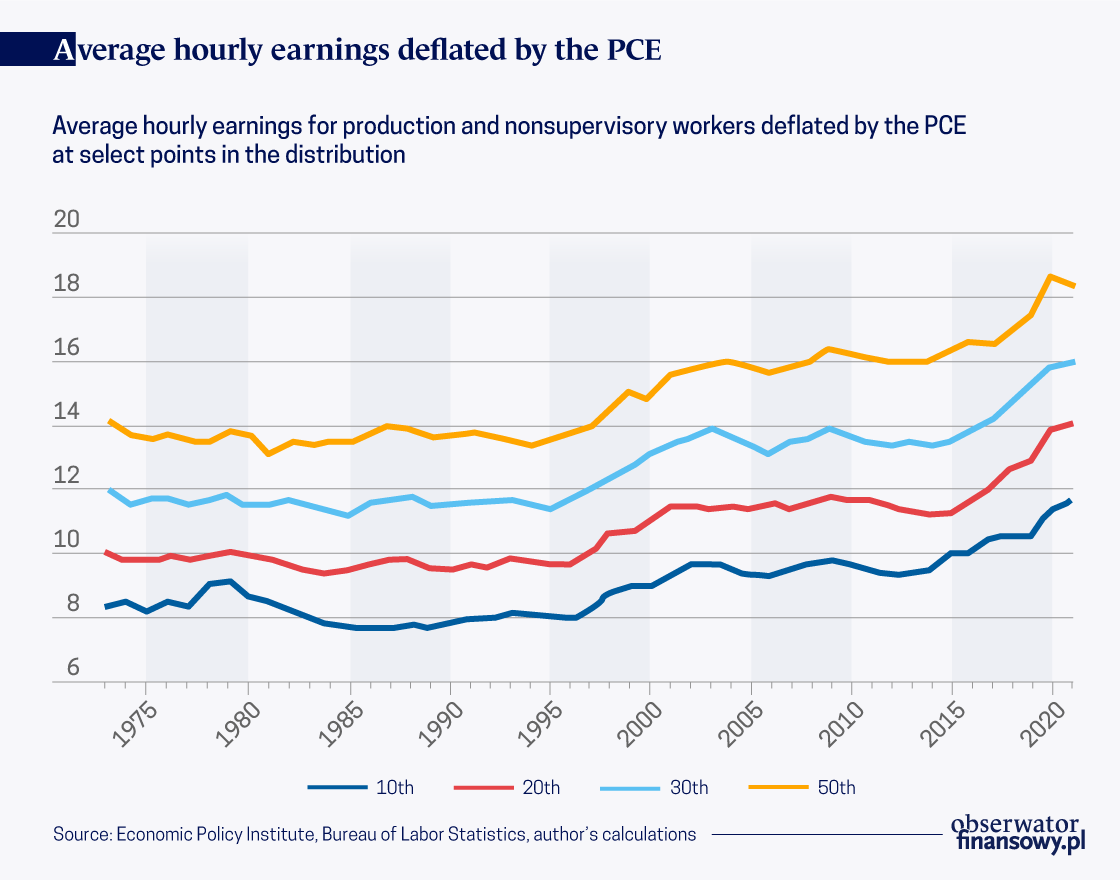

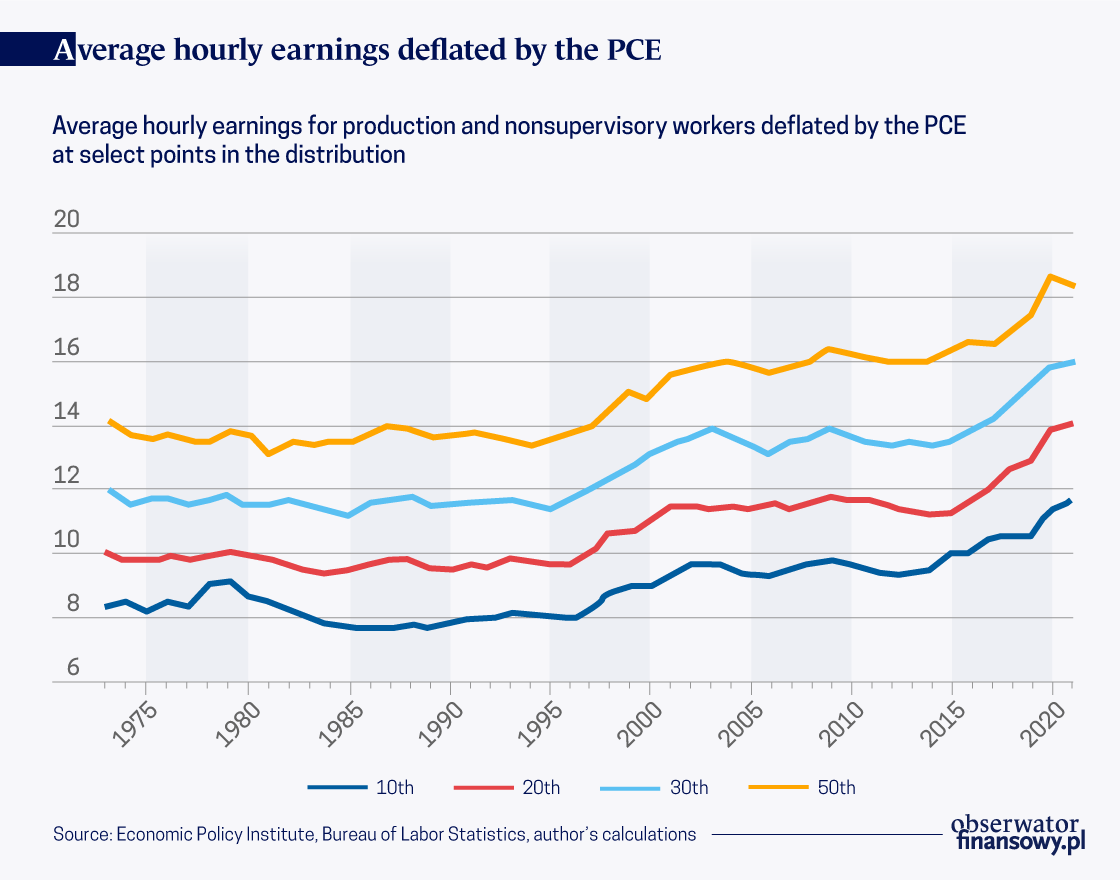

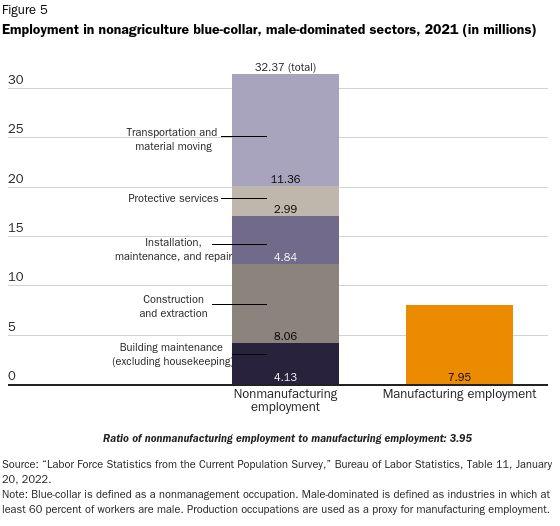

In some important ways, the plight of the typical worker has been oversold—a product, at least in part, of the widespread market pessimism that we discussed just last week. As previous Capitolisms and my other work have detailed, for example, the latest data debunk frequent populist laments about middle class income “stagnation,” ever-increasing “inequality,” the “hollowing out” of the American middle class, and the “two-earner trap.” AEI’s Michael Strain recently updated the income data, finding even bigger gains for real wages between 1990 and 2022: 50, 48, 38, and 39 percent increases at the 10th, 20th, 30th, and 50th (median) percentiles, respectively:

Indeed, a lot of the “job-ism” in Washington these days—at least the stuff that isn’t simply wrong—seems to be stuck in a “post-Great Recession mindset,” ignoring that most economists in 2022 have been far more worried about the labor market being too hot—as indicated by record-setting job openings, the “great resignation,” quickly rising private sector wages, and omnipresent labor “shortages”—than too cold. Even now, after the Fed interest rate hikes, “recession” debates, and stock market troubles, the weak U.S. labor demand of, say, 2011 is nowhere to be found. It’s labor supply that’s the big problem.

That said, things certainly aren’t perfect out there for American workers. Before the pandemic, for example, various measures of “labor dynamism” (workers moving from job to job or place to place) had been in a decades-long decline. Business dynamism (firm births, deaths, etc.), had also been dropping—a particular concern for workers considering a new business venture. And, as we’ve discussed, there’s been real weakness in particular pockets of the workforce, such as less-educated working-age men, while all workers—regardless of income or education—have faced rising costs of essential goods and services, especially in recent months. It’s thus no surprise, really, that policymakers and wonks have dedicated a disproportionate amount of time and attention to the “American worker.”

But has that time been well spent?

Does Most ‘Pro-Worker Policy’ Actually Help Most Workers?

Unfortunately, no. The most common proposals addressing the challenges facing American workers today—heavy on new government interventions in labor, trade, and other markets—ignore critical facts in critical ways, and might therefore not just fail targeted workers but also hurt the vast majority of others in the process.

First, the policies usually overlook the laundry list of current federal, state, and local policies that—while they might enrich politically powerful interest groups—harm most American workers and breed broader economic sclerosis along the way. As we’ve discussed a lot around here, current and proposed policies on things like occupational licensing, housing, childcare, healthcare, welfare, “gig” work, tariffs, and even criminal justice can end up depressing most Americans’ real (cost-adjusted) wages, labor force participation, new business formation, or mobility (economic or geographic). Even more absurdly, many of these same policies (e.g., steel tariffs) are often cloaked in “pro-worker” rhetoric, despite their well-documented harms for most of the workforce (e.g., workers in steel-consuming industries, who outnumber steelworkers by as much as 80 to 1).

Second, “pro-worker” policies routinely ignore the numerous market-based solutions that achieve the same objectives—boosting workers’ independence, mobility, wealth, resilience, or quality of life—without the inevitable economic and political problems that come with more spending and bureaucracy. Oftentimes, the solution is just to eliminate or reform the policies that are already screwing things up, but other issues, such as K-12 education, require new and creative solutions to longstanding problems—problems that other, more interventionist policies have failed to fix. In case after case, what’s needed isn’t some major new government program, “emergency” executive action, or fundamental rethink of capitalism (or whatever), but actually much the opposite: small, unsexy, but important increases in workers’ freedom to pursue the things they want to pursue (if governments would let them).

And that gets to the final—and perhaps most important—error: Many of today’s “pro-worker” policy proposals fundamentally misunderstand that today’s American worker is far different from the cookie-cutter models (e.g., a middle-aged, sole breadwinner male in a unionized, 9-to-5, assembly line job, or a single, college-educated, urbanite female) that those policies most often target. Surely, some American workers conform to those stereotypes, but far more don’t—because the “American worker” politicians love to champion is actually a wildly diverse group of distinct individuals across a wide range of industries and localities, each with his or her own goals, desires, and skills.

For example, while we continue to hear both Republicans and Democrats crow about “saving” American manufacturing jobs via protectionism and industrial policy, most workers today (female and male) work in industries other than manufacturing, whose share of the workforce (today about 8 percent) has declined steadily since 1953 (about 32 percent). As we’ve discussed, this isn’t because of politicians’ inattention or some sort of blind dedication to “free market fundamentalism,” but because of seismic global factors similarly affecting most every industrialized nation (and now China too).

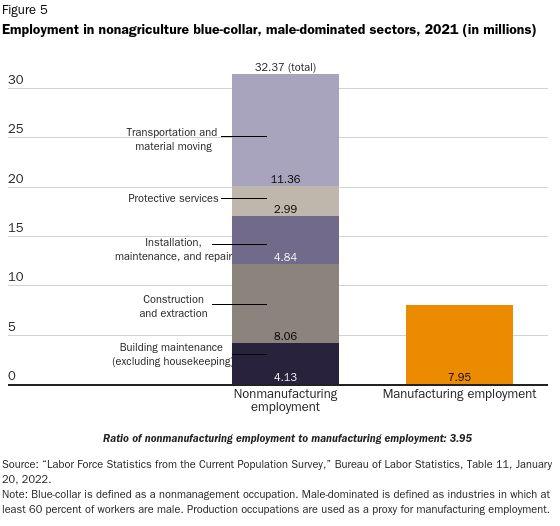

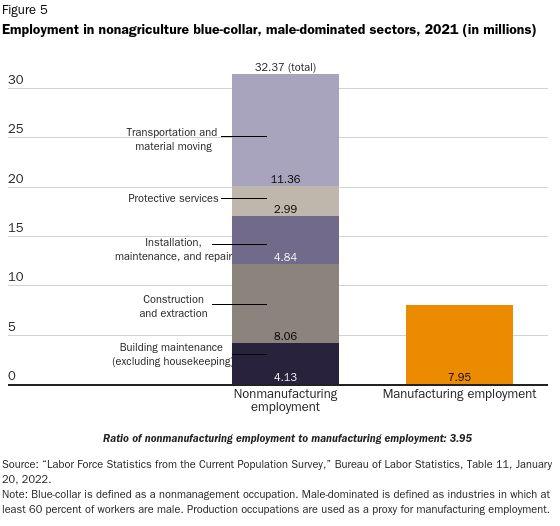

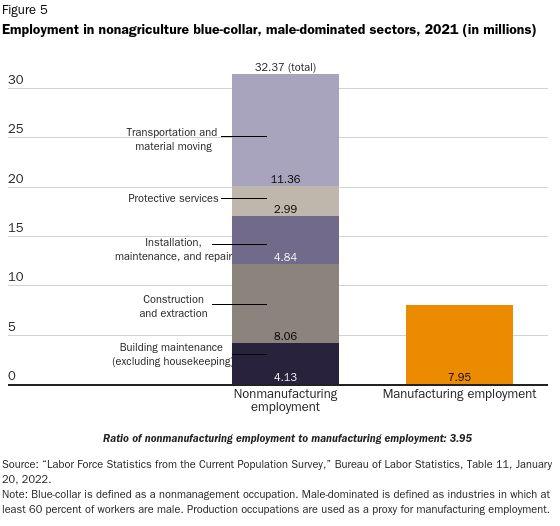

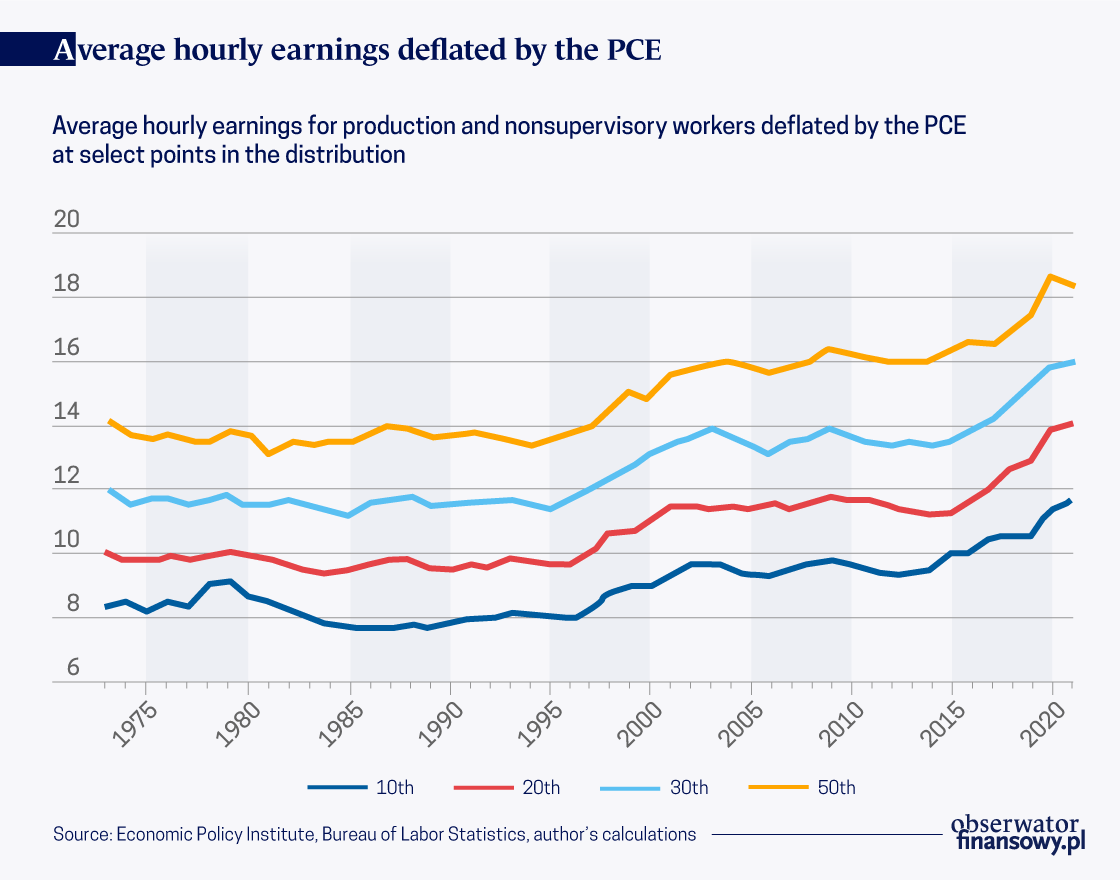

In 2021, in fact, the number of “blue-collar,” male-dominated nonmanufacturing jobs in the United States outnumbered nonsupervisory manufacturing jobs by a nearly 4-to-1 margin:

Thus, ostensibly “pro-worker” policies that protect or subsidize manufacturing to help certain “disadvantaged” demographic groups (e.g., less-educated males) often do so at the direct expense of not only most of the American workforce but also other industries that are home to these very same American workers (and lots more of them). This makes little sense.

The conventional wisdom on manufacturing also remains soaked in the aforementioned job-ism, which assumes that the current U.S. manufacturing job situation is due to a lack of demand for workers (caused by globalization or automation, for example). In reality, there’s little evidence of a widespread labor demand problem: In the first quarter of 2022, for example, there were about 850,000 unfilled manufacturing job openings, and new research estimates that this figure could hit 2.1 million by 2030.

Other trends in manufacturing also defy the Beltway conventional wisdom. For example, two new Federal Reserve studies have found that non-management workers’ longstanding “wage premium” in manufacturing (versus the same workers in non-manufacturing jobs) has essentially disappeared. Furthermore, many of the manufacturing jobs of tomorrow will actually be in services (e.g., industrial robot maintenance and repair) or require advanced skills and post-secondary education—far different from the routine assembly line jobs of the past that required only a high school degree. As of 2021, in fact, more manufacturing workers above the age of 25 had an associate’s degree or higher (45.1 percent) than had, at most, a high school degree (40.2 percent), continuing a trend of increasing education in the sector that dates back decades.

In short, there are plenty of “manufacturing jobs” out there—for those who want and can qualify for them. Far too many “pro-worker” manufacturing policies ignore all of this.

This doesn’t mean, of course, that all American workers now must aspire to attain a traditional four-year bachelor’s degree—far from it. Today, for example, online educational institutions—driven in part by the pandemic—have become increasingly popular and well-respected, and companies like Google have launched certificate programs that they’ll treat as the equivalent of four-year degree:

Non-college pathways also are increasingly promising: Store managers at Whole Foods can make well more than $100,000 without a degree; employer-led apprenticeship and retraining initiatives successfully vault participants into a similar pay range; and massive retailers like Amazon, Walmart, and Target employ millions of Americans and are constantly pushing the compensation envelope (and each other). Heck, Walmart this year announced that store managers can make $200,000 per year, and first-year truck drivers will make up to $110,000, with both training and licensing paid by the company. (And they’re still struggling to find workers.)

The assumed necessity of college might also be changing. For example, the “wealth premium” that American college grads long enjoyed over their noncollege peers has shrunk dramatically in recent years, and the unemployment rate for young college graduates has actually exceeded the rate for all workers since 2018 (though young college grads still enjoy some, albeit shrinking, employment advantage over non-college workers of the same age). A brand new study further finds that “[l]abor market outcomes for young college graduates have deteriorated substantially in the last twenty five years, and more of them are residing with their parents.”

In short, college isn’t for everyone, nor does it need to be—and Americans appear to understand that (while many policymakers don’t):

The pandemic has also accelerated fundamental changes to workers’ relationships with their workplace. Most obviously, there’s been a dramatic rise in remote work: The Census Bureau reports, for example, that 30 percent of employed adults reported in February 2022 that they worked remotely most or all of the time (up from 6 percent in 2019). The Los Angeles Times adds that, even with lots of workers returning to the office this spring, “about 30% of all paid workdays are still being done from home, up from just 5% before the COVID-19 outbreak.” Per McKinsey, this translates to tens of millions of additional American workers now working from home all or most of the time. They and others further report that most workers prefer these new arrangements, and that these new “teleworkable” jobs are available not merely to wealthy or college-educated workers, but also to those with less education or income.

Independent (contract) work is also changing—and again in surprising ways. Between 2017 and 2021, for example, the share of workers categorized as “freelance” held steady at about 36 percent, but that share increasingly consisted of skilled workers—in computer programming, business consulting, marketing, information technology, and other services—while the percentage of temp workers declined. In 2021, in fact, more than half of all freelancers in the United States provided skilled services or labor. By contrast, IRS data show that only about 9 percent of all independent workers are employed in “gig” work.

The pandemic-era increase in new businesses, which we first noted in late 2020, also has continued in 2021 and 2022:

The data show, moreover, that this isn’t just about knowledge work or gig work—Americans are going out on their own in all sorts of industries:

Trends in remote work, independent work, and new business formation show that many American workers, especially younger ones, increasingly value flexibility, autonomy, and lifestyle above higher wages or traditional office perks. New research finds, in fact, that many employers have offered remote work options to temper wage increases because their workers so value this new amenity more than a slightly larger paycheck. Freelancers say control over their schedule and location flexibility are among their biggest key motivators; gig workers report much the same. Even in manufacturing, prospective workers today increasingly value personal well-being, work flexibility, and geography above other employment attributes.

Recent policies seeking to mandate wages and benefits, tie workers to specific places or firms, ban independent work, or restrict certain types of businesses and professions are again oblivious to these trends.

These and other policies also seem unaware of recent changes in Americans’ personal lives. According to new research from the University of Texas, for example, approximately 70 percent of American mothers can today expect to be the primary breadwinner in their household for at least one year, and this trend is mostly about married moms, not unmarried ones. Meanwhile, COVID-19, remote work, altered family priorities, and other factors may be changing the long-held assumptions that decades of Americans moving to coastal cities and parents working away from home would continue indefinitely. Suddenly, Americans are moving back to the suburbs, and the country’s hottest job markets are in small or midsize cities in the Sun Belt and Midwest. And working parents, after juggling childcare and children’s schooling, have stronger preferences for flexibility, remote work options, and starting their own businesses.

No, this doesn’t mean that cities are “dying” (ahem), or that no Americans want that pre-pandemic two-earner lifestyle. But it does mean that workers’ priorities are not only diverse but also constantly changing—something that static, presumptuous U.S. labor, housing, transportation, and other policies routinely miss.

Finally, the American worker is increasingly globalized, contrary to the common assumption in Washington—sadly on both sides of the aisle—that protectionism and nativism are “working class” policies. For example, a new study has found that, while American companies engaged in international goods trade constituted only 6 percent of all U.S. companies in 2021, these “goods traders” accounted for half of U.S. jobs that same year (in a wide range of industries) and generated about 60 percent of all net new U.S. jobs since the Great Recession (mainly via startup businesses). Even in manufacturing, goods traders saw net job creation since 2011 because they adapted to new import competition and thrived thereafter; non-trader manufacturers, on the other hand, struggled (especially in labor-intensive industries like apparel and leather goods).

Leaving aside the many other benefits of trade and foreign investment for the economy, this is a compelling case against “worker-centric” protectionism and for greater international engagement. Maybe somebody could tell the White House?

So What Should “Pro-Worker” Policy Look Like?

Overall, these trends show that the “American worker” in Washington and statehouses across the country often bears little resemblance to the U.S. workforce’s complex and ever-changing reality, and that a new approach is sorely needed. This doesn’t argue, however, for crafting new “pro-worker” policies based on today’s “new normal.” Instead, policymakers should generally (1) stop targeting a certain kind of American worker, promising cradle-to-grave protection from inevitable disruptions, or presuming to know tomorrow’s employment and lifestyle trends; and (2) embrace market-based policies that lower costs generally and maximize individual workers’ autonomy and mobility, so that they can choose the careers and lifestyles that they (not politicians) want and can more easily adjust to whatever “normal” comes next.

There are oodles of potential policies that fit this bill, but some of the most important ones will be featured in a forthcoming book—officially released this winter but rolled out in parts throughout the fall—that I’ve been editing and writing, with several Cato colleagues’ help, for most of this year. (I revealed some early book cover ideas last week, if you’re interested.) Among the 17 subject chapters are the obvious issues like education, remote work, childcare, and licensing, but also ones that greatly affect many of today’s workers but get less attention, like home-based business, criminal justice, and essential goods (food, clothing, etc.). Each chapter will identify current problems and their causes, and then will suggest pro-market ways for federal, state, and local policymakers to fix them—empowering all American workers in the process. It’s a great project (if I do say so myself), and I’m excited to share more of it with you soon. (This column is a first taste.)

As detailed in the book, market-based reforms across a wide spectrum of issues not only would boost American workers’ freedom and resilience, but would also likely make them better off—and not merely by lowering the prices of various necessities (though that’s certainly good too). According to a new study, for example, workers in more “fluid” labor markets like the United States enjoyed higher lifetime wage growth, lower unemployment, and greater productivity than their counterparts in places like Europe with more regulation and worker “protections.”

By contrast, the same study finds that supposedly “pro-worker” policies that reduce mobility, raise employer costs, and pigeonhole workers into certain preordained jobs or workplace arrangements significantly reduce workers’ lifetime earnings, career advancement, and skills accumulation—thus harming a nation’s overall labor productivity and economy more broadly. Recent evidence reinforces these findings: Europeans with more labor “protections”—including many that are very much en vogue today in Washington—are today struggling with involuntary underemployment. The more dynamic and less-regulated U.S. labor market, by contrast, has fully rebounded.

Put simply, pro-market policies are very much pro-worker policies too. And it’s time for Washington to relearn that lesson before it’s too late.

Capitolism will be off next week to celebrate Labor Day (because, hey, I’m an American worker too).

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.