Partisans in Washington don’t agree on much, but they thoroughly agree on China: It’s very bad, and U.S. protectionism—especially tariffs—is very good. In the White House, U.S. trade policy toward China was effectively unchanged in the transition from Trump to Biden, with the only notable shift being Biden’s recent tariff increase on certain “strategic” Chinese goods. Just last month, the House of Representatives held a much-ballyhooed “China Week,” in which 25 different China-related bills were passed with large, bipartisan majorities. And on the campaign trail, both Donald Trump and Kamala Harris (along with Rs and Ds running alongside them) routinely mention China as either a villain or a justification for their various domestic policies.

We’ve already detailed the tariffs’ costs here at Capitolism: higher taxes and higher prices paid by U.S. businesses and consumers; fewer sales by U.S. exporters; billions in subsidies to bail out politically connected farmers; less U.S. investment due to policy uncertainty; and so on. But we’ve done less on whether the tariffs are actually succeeding as part of some grand strategy to cripple Beijing and reduce U.S. “dependency” on China and Chinese companies. Maybe all those costs are, like, totally worth it if they keep Chinese content away from the U.S. market and hurt the CCP as a result. And six-plus years of tariffs—five of which at the high levels they remain today—should give us a pretty good idea of whether the tariffs are working.

Spoiler: They really aren’t. And nobody should be surprised.

Decoupling? Not So Much

The good folks at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) provide a snapshot of how the U.S.-China tariff battle progressed through 2023:

As you can see, the tariffs and Chinese retaliatory actions started in mid-2018 and really cranked up in 2019, reaching levels that have more or less remained steady since that time. The only big change, as mentioned above, is the Biden administration’s decision to apply even higher tariffs on a select group of Chinese products, such as electric vehicles, batteries, and semiconductors—tariffs that started entering into force last week.

At a broad, superficial level, it may seem that the U.S. and Chinese economies are indeed decoupling, as China’s share of all U.S. imports has declined substantially from its 2017 peak of 21.6 percent to just 13.2 percent last year. Dig a little deeper, however, and the decoupling—and any reduced U.S. “dependency” on Chinese content—looks a lot more modest.

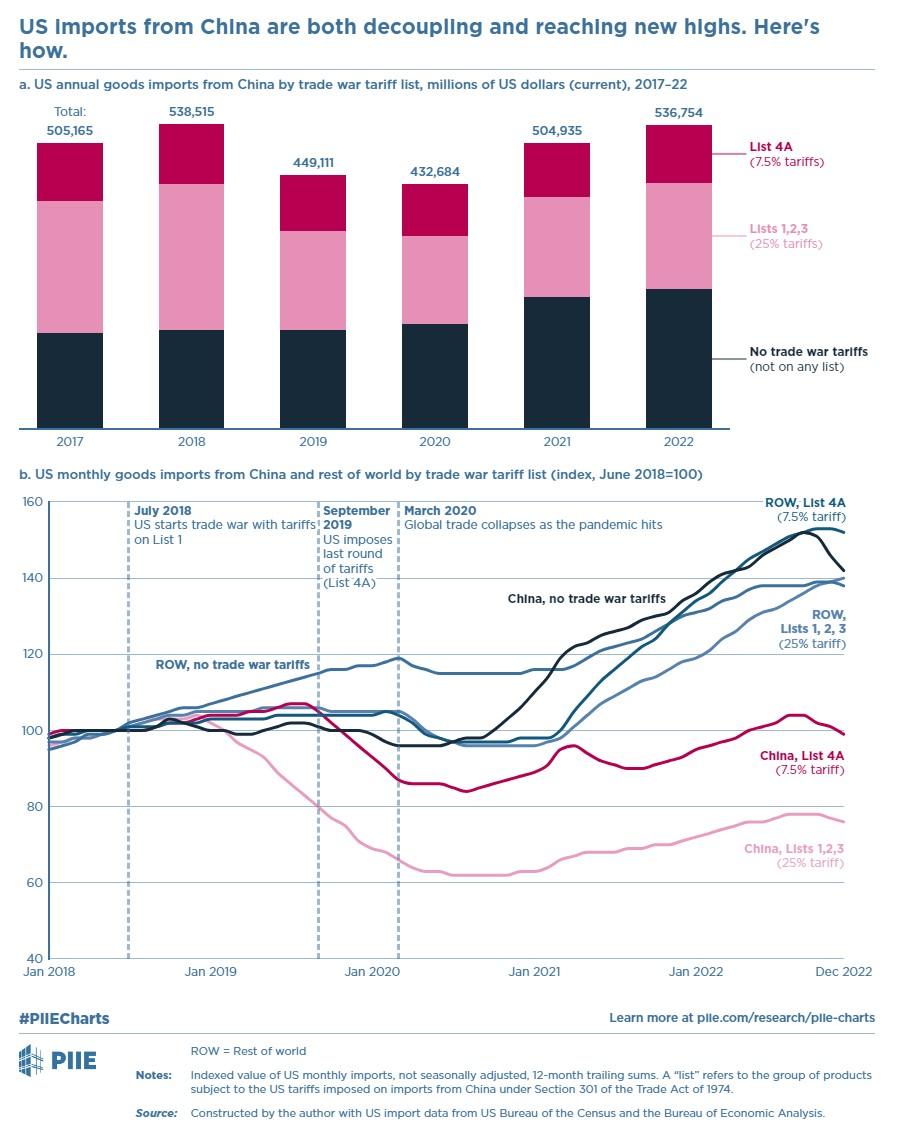

For starters, the U.S. still directly trades a lot of goods with China. As of the latest 2024 data, China is still our third-largest import and export market, behind next-door neighbors Canada and Mexico. Some of this continued engagement is because, as PIIE’s Chad Bown documented last year, following U.S. tariffs there was a significant increase in non-tariffed China-origin goods—many of which (e.g., smartphones) haven’t been taxed because of such taxes’ clear and direct harms to U.S. consumers:

Furthermore, Bown’s data also show that even targeted imports from China didn’t collapse in the wake of new U.S. tariffs. Instead, many of those goods continued to reach the U.S. market with new taxes attached—taxes that (again!) American companies and consumers have simply been paying (to the tune of tens of billions of dollars).

Second, companies in the United States and abroad have used several legal mechanisms to bypass U.S. tariffs and get Chinese content into the country. Most notably, multinational manufacturers have moved final assembly operations from China to Vietnam, India, Malaysia, Mexico, and other non-China countries, so that they can still utilize a lot of Chinese parts and other materials but avoid—again, lawfully—a “made in China” label (and thus U.S. tariffs). It’s difficult to calculate the precise amount of tariff-fueled supply chain reconfiguration that occurred in recent years, but several studies have found tight linkages between increased U.S. imports from third countries and increased Chinese exports to those same countries, thus indicating that this activity has been substantial. Vietnam is probably the clearest example:

Data show that much of Vietnam’s exports to the U.S. are parts, or components, produced in China. The Asian Development Bank estimates that imported parts account for 80 percent of the value of Vietnam’s electronic exports in 2022. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development said in a report that 90 percent of goods imported by Vietnam’s electronics and clothing industries in 2020 were then “embodied in exports.” That number, the organization said, was higher than in earlier years and far above the average in industrialized countries. In the first three months of 2024, U.S. imports from Vietnam added up to $29 billion, while Vietnam's imports from China totaled $30.5 billion.

Darren Tay is the lead economist at the research company BMI. He said, “The surge in Chinese imports in Vietnam coinciding with the increase in Vietnamese exports to the U.S. may be seen by the U.S. as Chinese firms using Vietnam to skirt the additional tariffs imposed on their goods.”

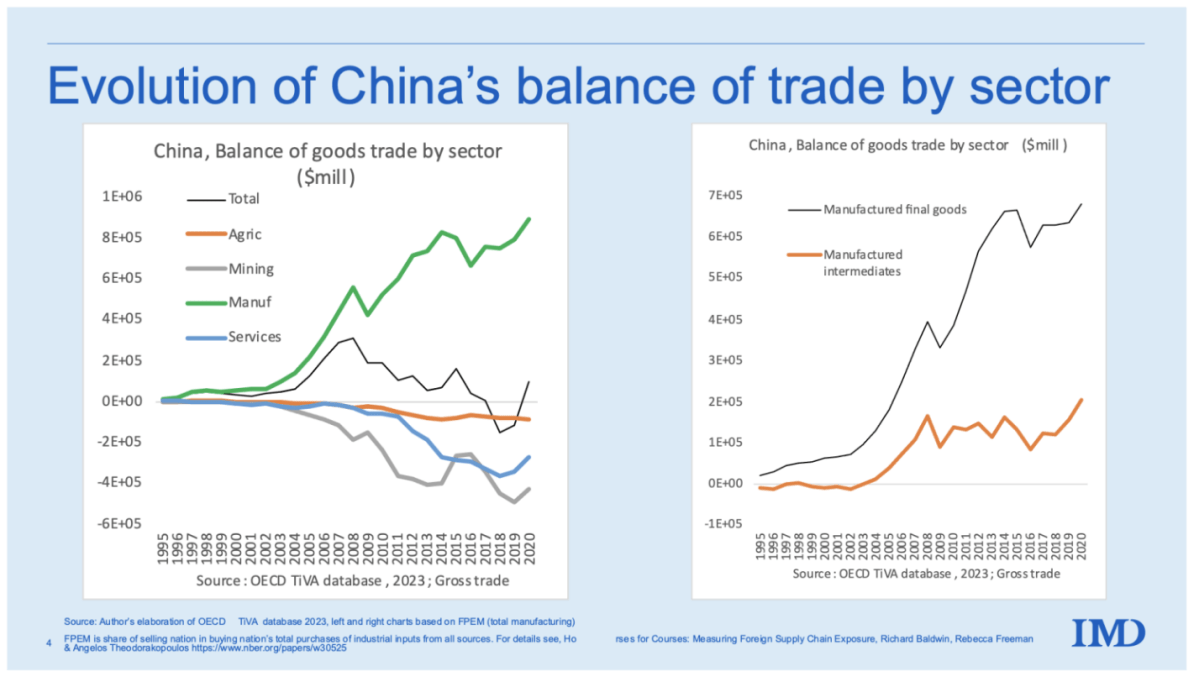

Economist Richard Baldwin further shows that China is a huge and growing net exporter of manufacturing inputs (aka “intermediate goods”), with a prominent spike occurring right as Trump took office:

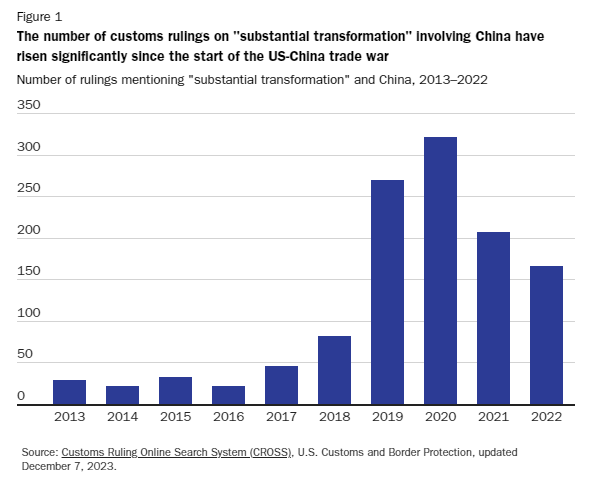

Other anecdotes and datapoints reinforce the conclusion that lots of Chinese content is entering the United States as “Made in Not China” goods. For example, companies considering a supply chain move (China-related or otherwise) can ask U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to examine the proposed changes and determine the applicable country of origin and U.S. tariff rate for the good at issue. In general, CBP will find that imported product legally “originates” in the last country in which that item underwent a “substantial transformation,” and the agency issues rulings that confirm this activity in order to give traders and manufacturers confidence in their supply chains and related paperwork. And these rulings show a massive spike in China-related rulings after the tariffs were first proposed. As shown below, in fact, there were seven times more customs rulings mentioning “substantial transformation” and “China” in the five years after the tariffs (2018-2022) than in the five years before (2013-2017):

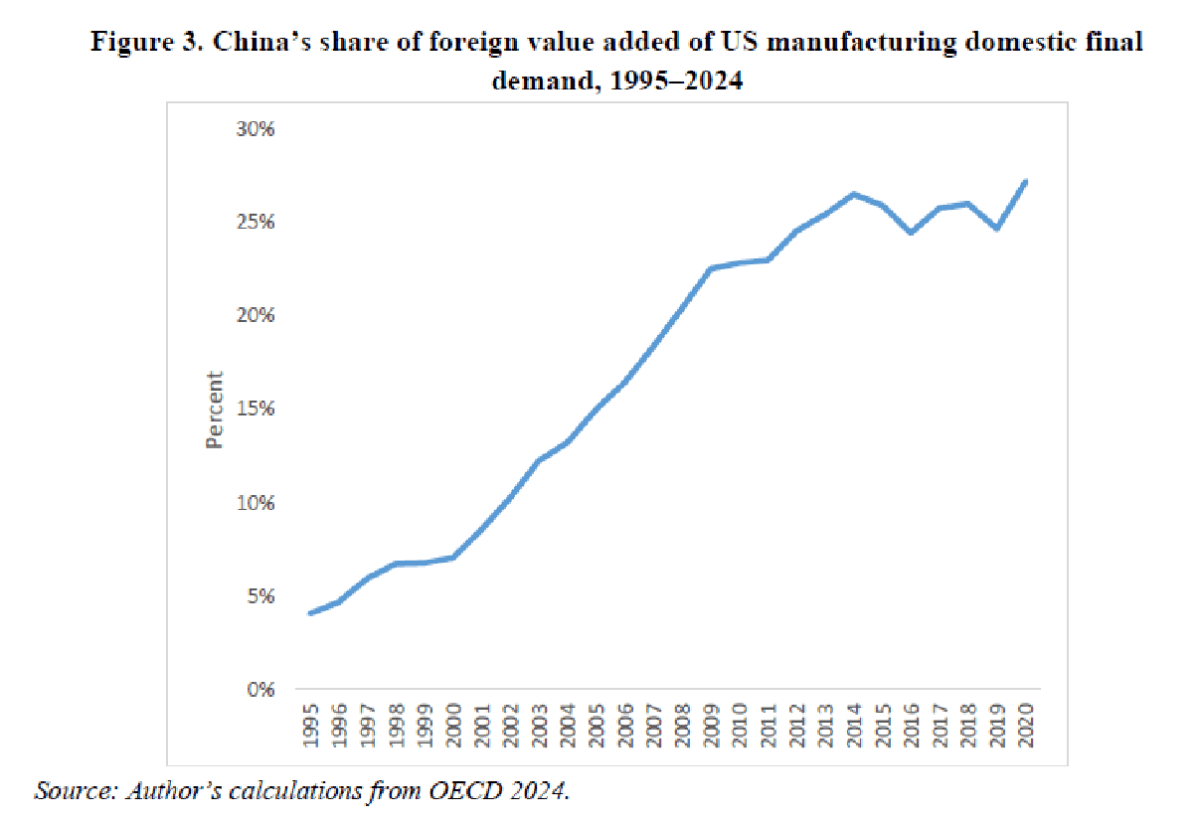

Overall, the American Enterprise Institute’s Michael Strain shows in a forthcoming paper for the Aspen Economic Strategy Group that the amount of Chinese manufacturing content (aka “value-added imports”) entering the United States in 2020 (the last year available) remained at its pre-trade-war peak:

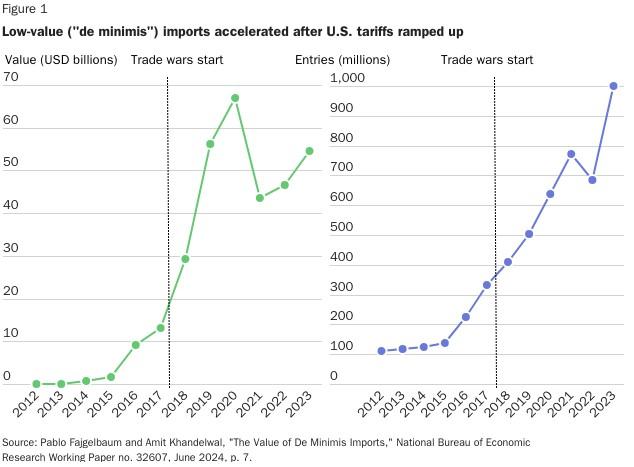

Another form of legal tariff evasion relates to low-value, direct-to-consumer shipments (called “de minimis” imports). Under U.S. law, each American can directly import up to $800 in stuff without paying tariffs or facing certain other customs formalities—a practice that used to apply mainly to overseas travel purchases but today is used for lots of modern e-commerce transactions. The de minimis exception is today controversial (and subject to lots of misinformation about abuse and public safety), but two things from the data aren’t debatable: Its use ramped up dramatically after the U.S.-China trade war began, and China was the main country of origin for these shipments.

Today, companies like Shein and Temu have exploded in popularity and size by utilizing direct-to-consumer shipments, but other companies and customers have certainly followed their lead. (In fact, the latest data from the American Action Forum show that Chinese goods are a declining share of all de minimis shipments, though still a substantial majority.) Overall, a new study shows that poor American consumers have disproportionately benefited from this trade and would thus be disproportionately harmed should the de minimis rule be changed. Regardless, it’s quite safe to say that the measure wouldn’t be nearly as popular or controversial today if it weren’t for U.S. tariffs. As Bloomberg put it in 2021, “Trump’s Trade War Built Shein, China’s First Global Fashion Giant.” Oops.

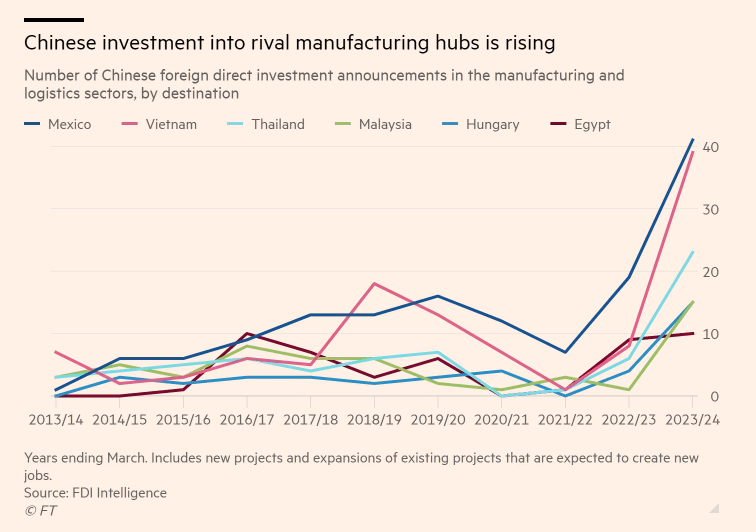

The continued economic linkages extend beyond China-origin content. For example, recent studies show that Chinese multinationals are investing in manufacturing and related operations in third countries, in part to avoid U.S. tariffs:

This means that “Chinese” stuff, such as EVs made in Mexico or batteries made in Morocco, might soon be exported tariff-free to the United States yet contain little actual China-origin content.

Maybe that kind of diversification is good for boosting supply chain resilience (or whatever), but—to the extent these China-related products do enter the United States—it’s not really “decoupling” at all.

As Morgan Stanley’s chief Asia economist, Chetan Ahya, documented in the Financial Times in August, these supply chain and investment moves, along with currency adjustments and increased Chinese sales of finished goods to non-U.S. markets, have greatly weakened the effect of U.S. tariffs on China’s export machine. In fact, the Chinese share of global goods exports actually increased significantly between pre-tariff 2017 (12.8 percent) and 2024 (14.4 percent):

This doesn’t mean, of course, that China’s economy is humming along. As we’ve discussed, it’s actually doing much the opposite. Nevertheless, the vast majority of those economic problems are owed to China’s own internal problems—a continued property bust, serious demographic headwinds, a disastrous zero-COVID lockdown, subsidy-driven resource misallocation, lagging productivity, consumer (especially youth) disillusionment, CCP hostility to public data and private business, etc. They’re not the result of U.S. tariffs. Those surely had some effect, as has the overall geopolitical climate, but the tariffs themselves were likely a small contributor to the country’s declining economic prospects.

And, again, the actual “decoupling” has (thus far) been much less significant than advertised.

Strategy? What Strategy?

Meanwhile, there’s plenty of evidence undermining the idea that the China tariffs are an integral part of some broader strategy to contain China. For starters, the U.S. applies tariffs on many Chinese goods with no plausible national security or even “resiliency” nexus. This includes breast pumps, garage door openers, bagless vacuum cleaners, portable electric heaters, bicycles and bicycle frames, tiki torches, babies' blankets and swaddle sacks, cotton blankets, and blood pressure cuffs. I’ve yet to hear a remotely coherent explanation for why these tariffs are in any way “strategic” or otherwise necessary. And that’s because, as anyone who knows the tariffs’ history understands, the White House’s original strategy to target mainly high-tech manufacturing inputs linked to Chinese industrial policy went out the window when China first retaliated and Trump instantly vowed a massive U.S. escalation in response. So, after several U.S.-China tit-for-tats, we get to enjoy tariffs on bleeping baby blankets for no serious policy reason.

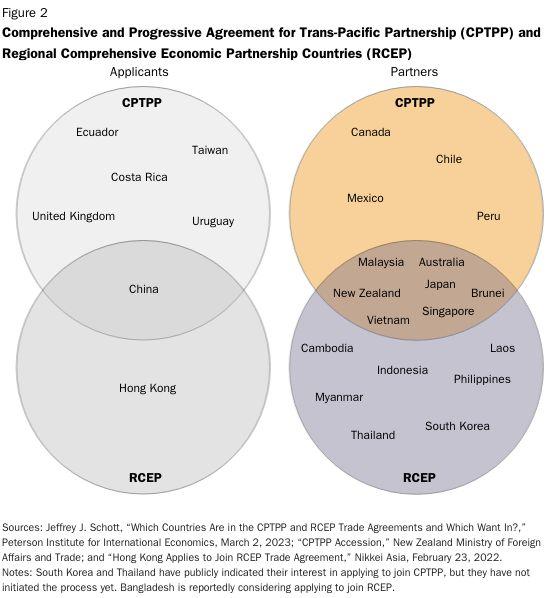

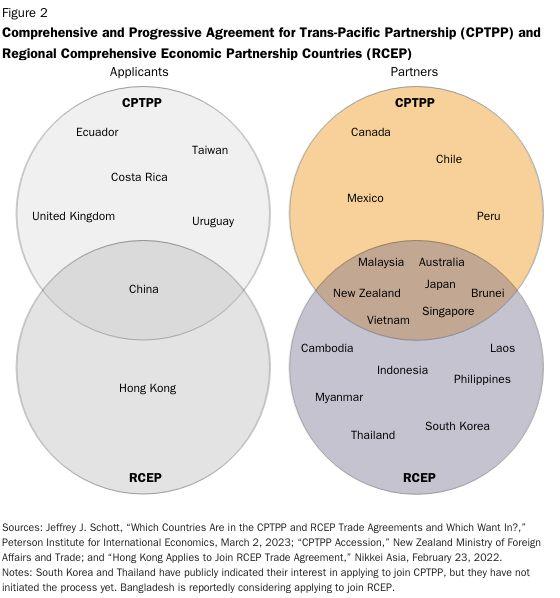

Just as importantly, the U.S. has shown little appetite for increasing trade with allies or China-alternative countries, and in many cases it has ramped up the protectionist hostilities. In particular, the Biden administration has maintained a total moratorium on comprehensive trade agreements, even as China and many other nations use them (and thus deepen their integration). So, for example, we continue to stiff-arm the Trans-Pacific Partnership (now called CPTPP) deal that Biden’s former boss Barack Obama championed to counter China’s economic and geopolitical gravity in the AsiaPac region, as China implements its own version (called RECP) and even applies to join the CPTPP:

The United States has also let unilateral programs offering limited duty-free access to imports from many developing countries expire (the Generalized System of Preferences) or sit on life support (the African Growth and Opportunity Act), thus discouraging trade with and investment in China-alternative countries. Even narrower agreements liberalizing digital trade, in which the United States has a massive comparative advantage, have seen the United States step back. Combined with continued U.S. resistance to letting the World Trade Organization function, these moves further isolate the United States, alienate potential friends, and embolden and empower China along the way.

Then there’s all the non-China protectionism. “National security” tariffs and quotas on steel and aluminum continue to be applied to imports from most of our closest friends, including Japan and Europe, and to things like rebar that have no plausible defense use. New industrial subsidies—in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Inflation Reduction Act, and CHIPS and Science Act—generally target and in some cases even mandate the onshoring of production, not “nearshoring” or diversification away from China. Both the Trump and Biden administrations have also touted enhanced “Buy America” restrictions on federal spending, despite their high costs and discrimination against close U.S. trading partners. “Trade remedy” (antidumping and countervailing duty) cases continue to proliferate against both industrial inputs and finished products, with non-China countries increasingly subject to duties. In this regard, Vietnam—long alleged by the government to be a solid non-China alternative—is particularly disadvantaged by a “non-market economy” status that the Biden administration just re-upped.

China, again, has done the opposite:

China has lowered the tariffs it applies on imports from the rest of the world. China's average tariffs toward those exporters have declined from 8.0 percent in early 2018 to 6.5 percent by early 2022. The United States increased its average tariffs on imports from the rest of the world from 2.2 percent to 3.0 percent over this same period.

Add to these miscues our overbroad, counterproductive sanctions and export controls hitting major U.S. companies and key U.S. allies “without accomplishing a strategic aim” (so says a supporter!). And then add on top of that all the non-trade stuff hobbling U.S. competitiveness, such as union favoritism and social policy attached to industrial policy, a refusal to embrace tax, regulatory and other supply-side reforms, antitrust attacks on Big Tech and other innovative U.S. champions, continued stasis on immigration policy, and—of course!—the whole Nippon Steel/U.S. Steel debacle. In this light, our “China policy” looks far less like some grand strategy for battling an existential geopolitical threat and far more like good ol’ fashioned electoral politics and economic protectionism.

Summing It All Up

And for what? As already noted, the tariffs probably have hurt China’s economy a bit, but they haven’t caused any serious economic pain there or any major reduction in American “dependency” on China-linked content. (And they hurt the U.S. economy too, of course.) Trump’s “Phase One” deal with China is dead; Chinese industrial policy and human rights abuses are unchanged (or worse); CCP authoritarianism and overseas belligerence have increased; and bilateral relations are lousy. In some cases, in fact, U.S. policy has emboldened Chinese nationalists and state-owned enterprises, while pushing private Chinese companies and many other nations closer to Beijing.

One can reasonably imagine a serious U.S. tariff policy that narrowly targets security-related Chinese products and is coupled with trade, immigration, and other economic reforms that seek to counter China by boosting connections with, and productive capacity in, both the United States and allied countries. But, aside from trillions of dollars in protectionist (and problematic) subsidies and the occasional rhetorical sop to “friendshoring,” we don’t have that at all. Instead, we’re kneecapping American allies, American exporters, American importers, and American champions, while increasing prices for American consumers of tiki torches, blankets, and other common items. It's a nonsensical mess.

The lessons here, once again, are that tariffs are a 19th century tool regularly thwarted by 21st century supply chains, and that politics regularly turns trade policy that might look decent on paper into a bloated morass resistant to reform. Too bad no one in Washington appears willing to learn them.

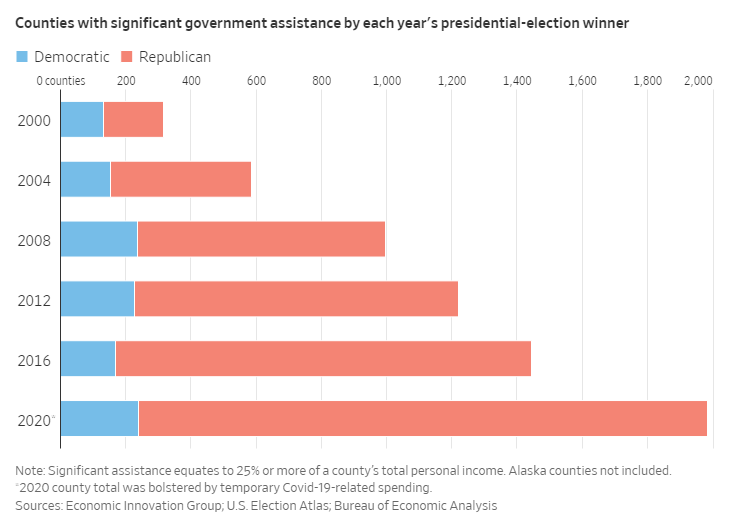

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.