Dear Capitolisters,

As you’ve probably seen, the Biden administration and various Democratic politicians have pivoted from pretending that inflation is NBD to blaming it on greedy corporations raking in record profits at COVID-stricken consumers’ expense. However, the claims of bad behavior about one industry in particular—U.S. supermarkets—say a lot more about the accusers than the accused, and undermine their broader case for expanding U.S. antitrust laws to attack corporate “bigness.”

Grocery Gouging?

Probably the most prominent example of recent political attacks on U.S. grocery store chains comes from Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who not only tweeted about the situation but also sent a sternly worded letter to the heads of Kroger, Albertsons, and Publix about how they reaped “massive profits” and “push[ed] grocery costs increases onto consumers” in 2021:

Warren may be the head cheerleader of the Democrats’ grocery gambit, but she’s certainly not alone. Indeed, the Federal Trade Commission—fresh off expanding its regulatory powers last June—has also gotten in on the act:

In late November, the Federal Trade Commission announced a wide probe into the grocery industry, asking nine key players to provide "detailed information to help the FTC shed light on the causes behind ongoing supply chain disruptions and how these disruptions are causing serious and ongoing hardships for consumers and harming competition in the U.S. economy.” The agency sent the orders to Walmart, Amazon, Kroger, C&S Wholesale Grocers, Associated Wholesale Grocers, McLane Co., Procter & Gamble, Tyson Foods and Kraft Heinz.

Alleged anti-competitive behavior by larger supermarkets has also driven up the cost of gas and extended travel times for especially rural and lower-income customers who must search further to get essential and at-times hard-to-find items like paper products and meat that “power buyers” have muscled away from smaller stores, local and regional grocers described in comments submitted to the FTC in late September.

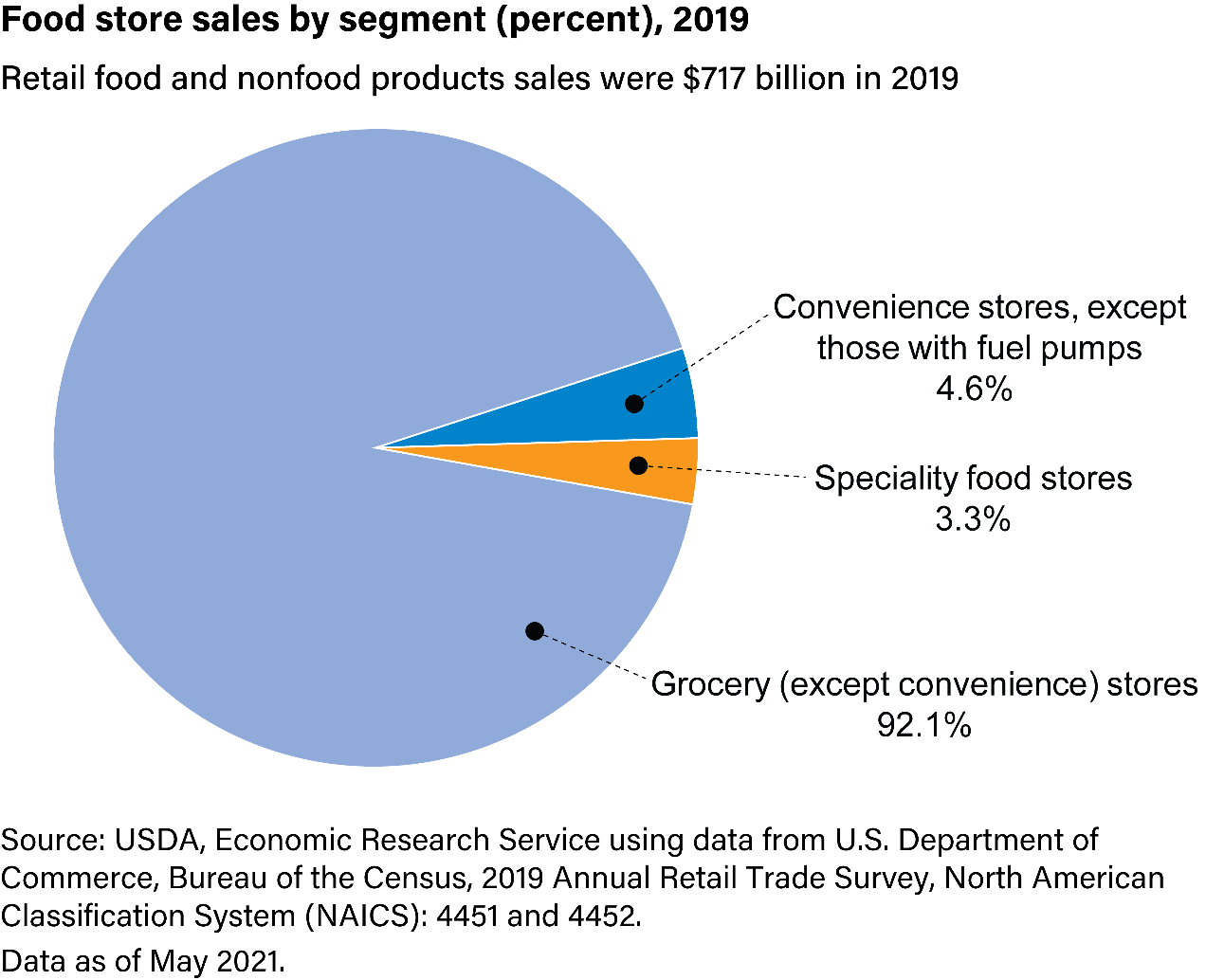

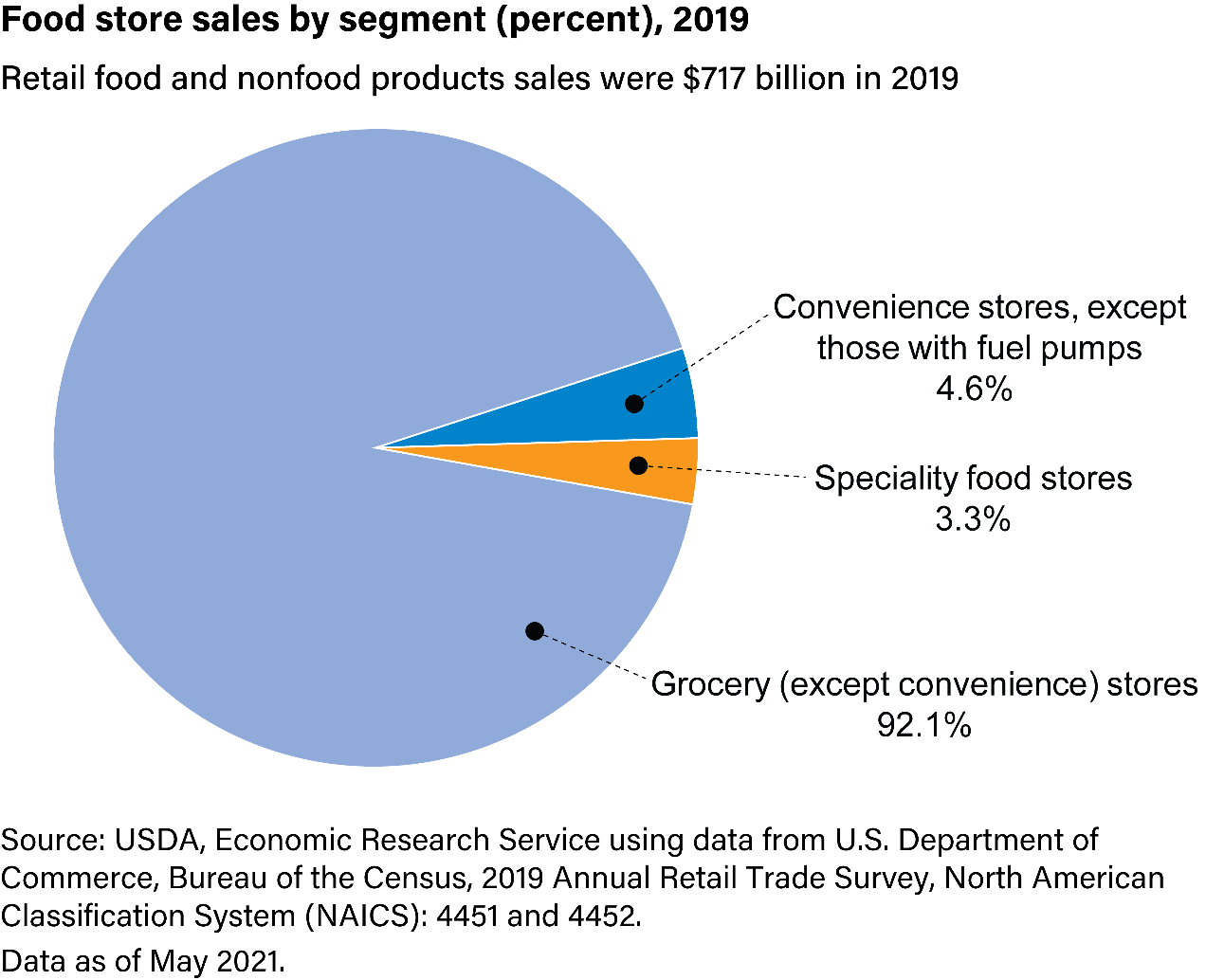

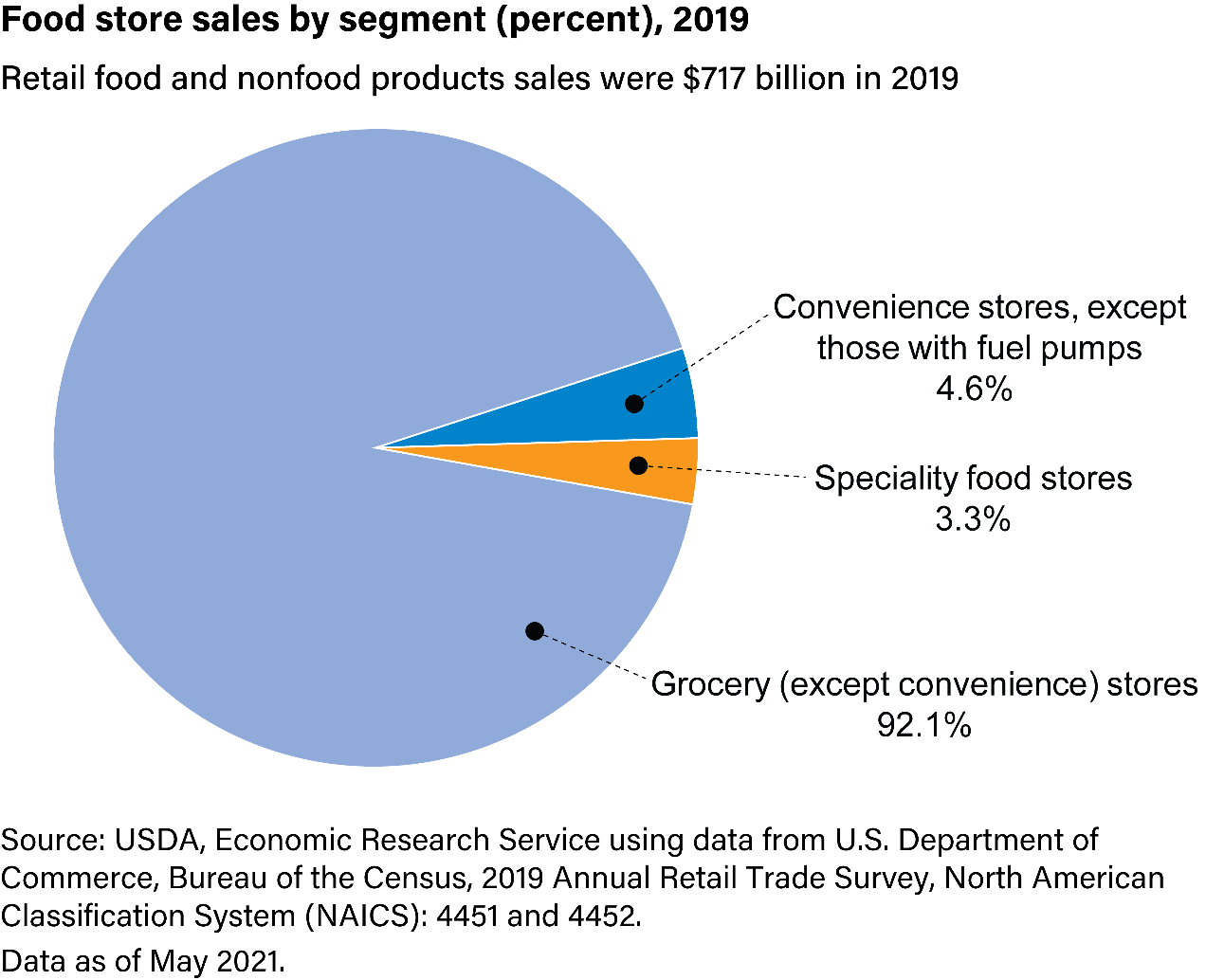

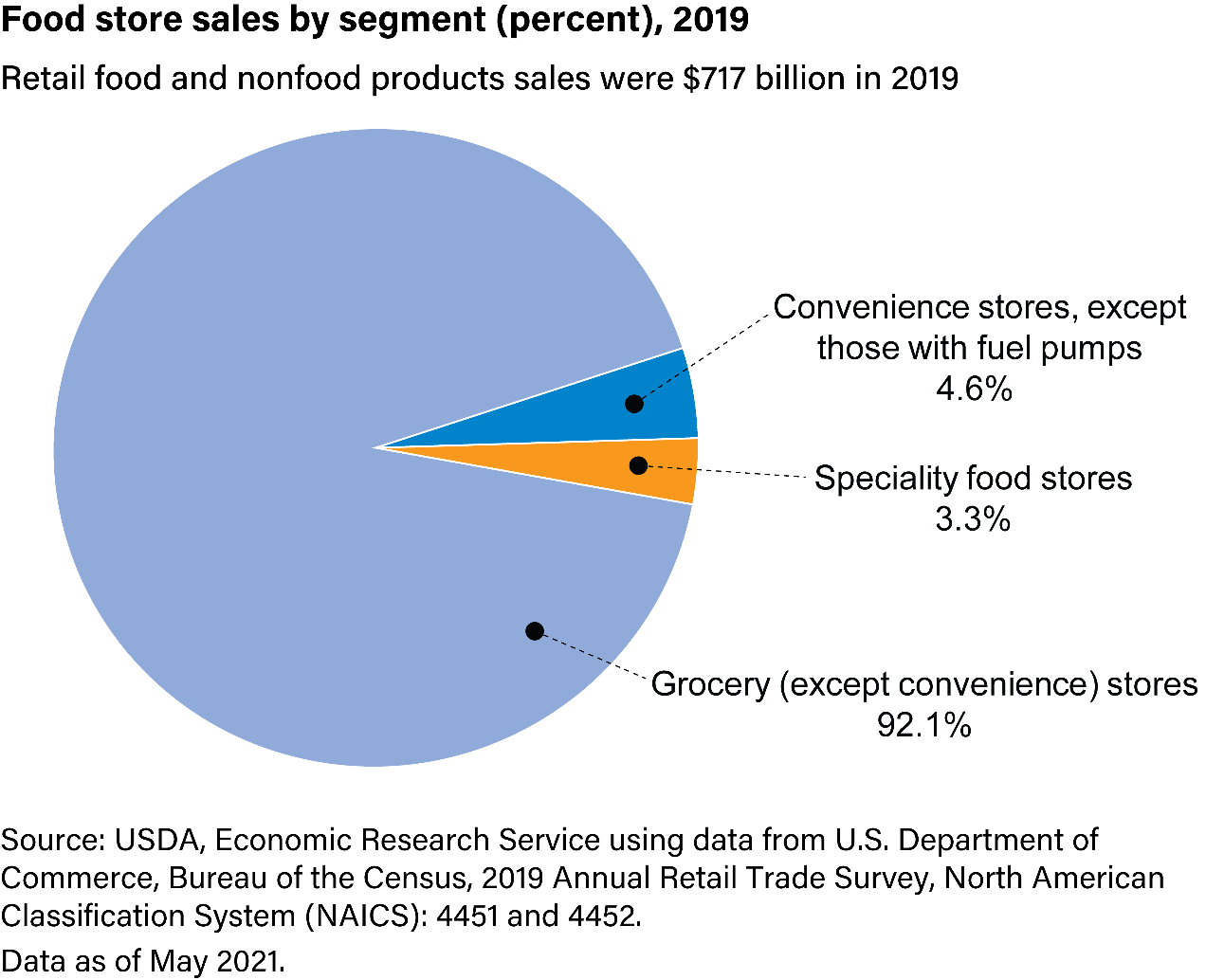

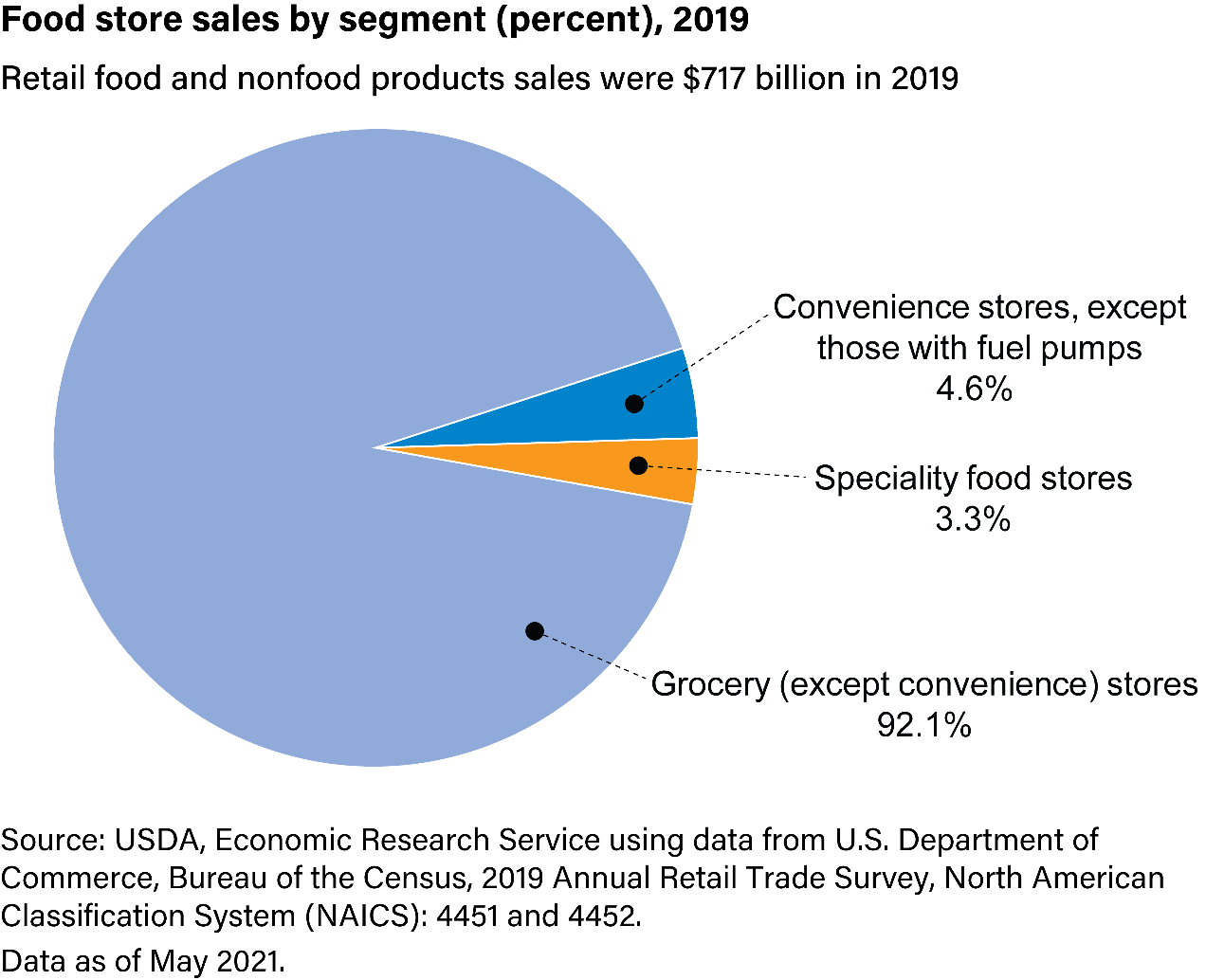

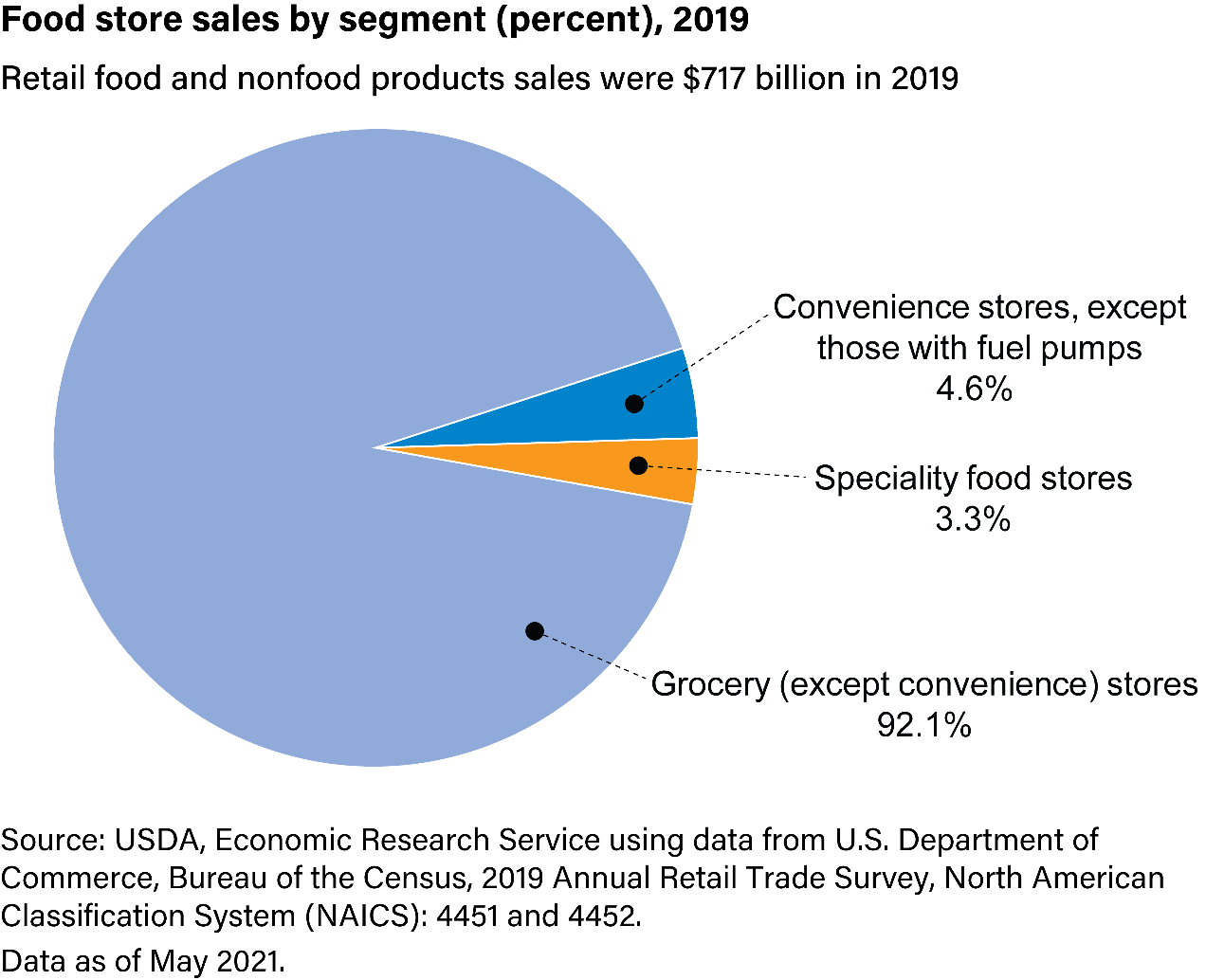

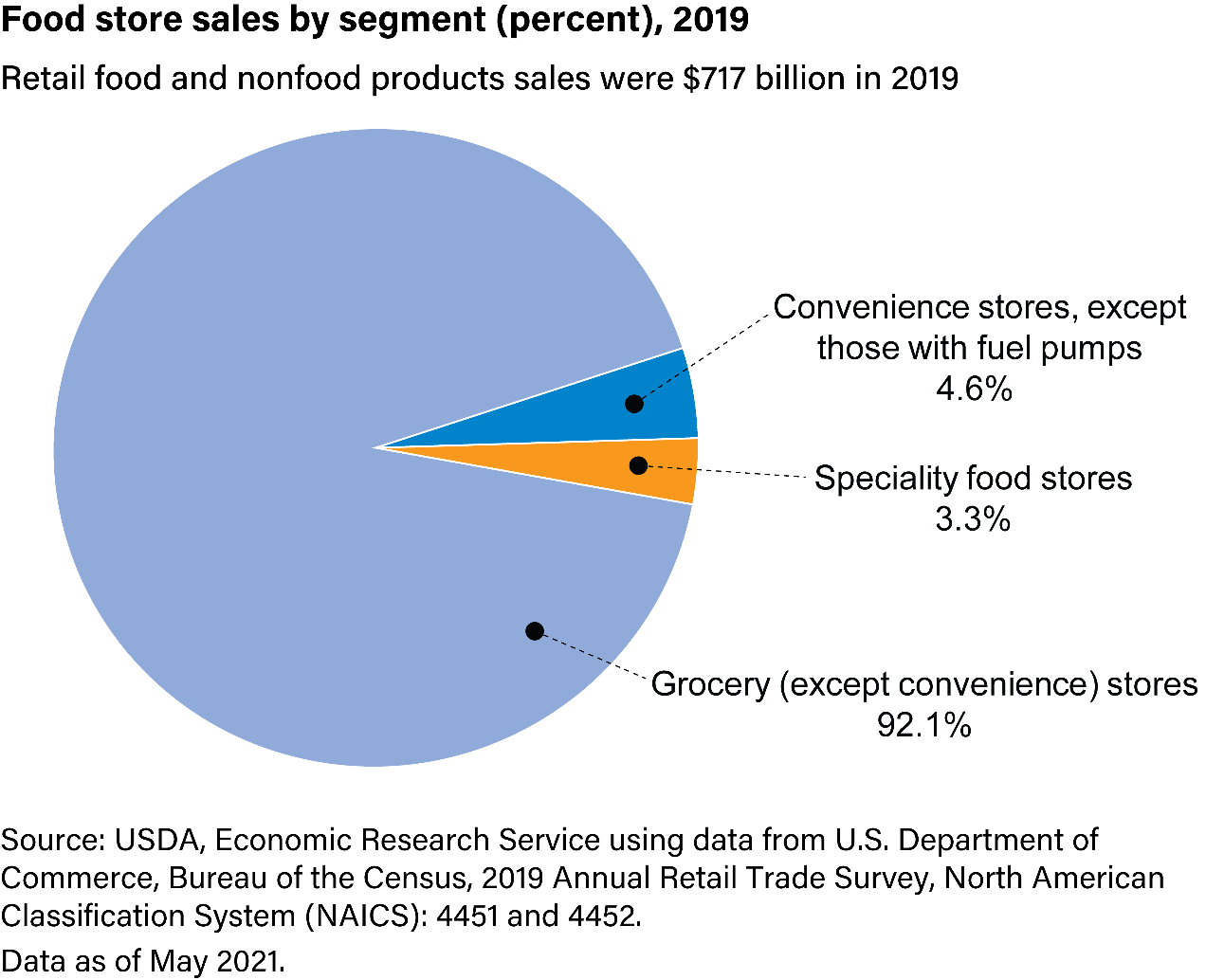

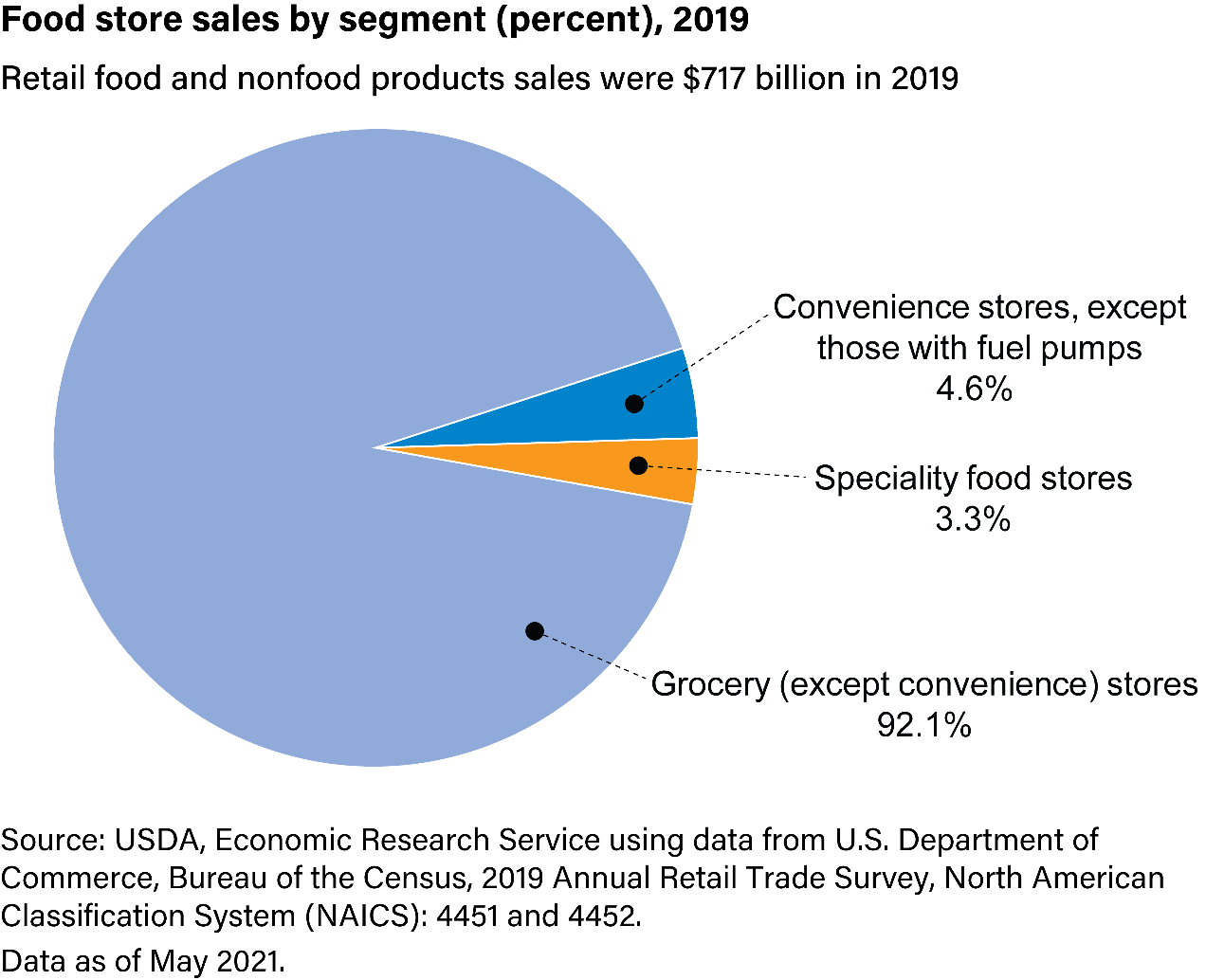

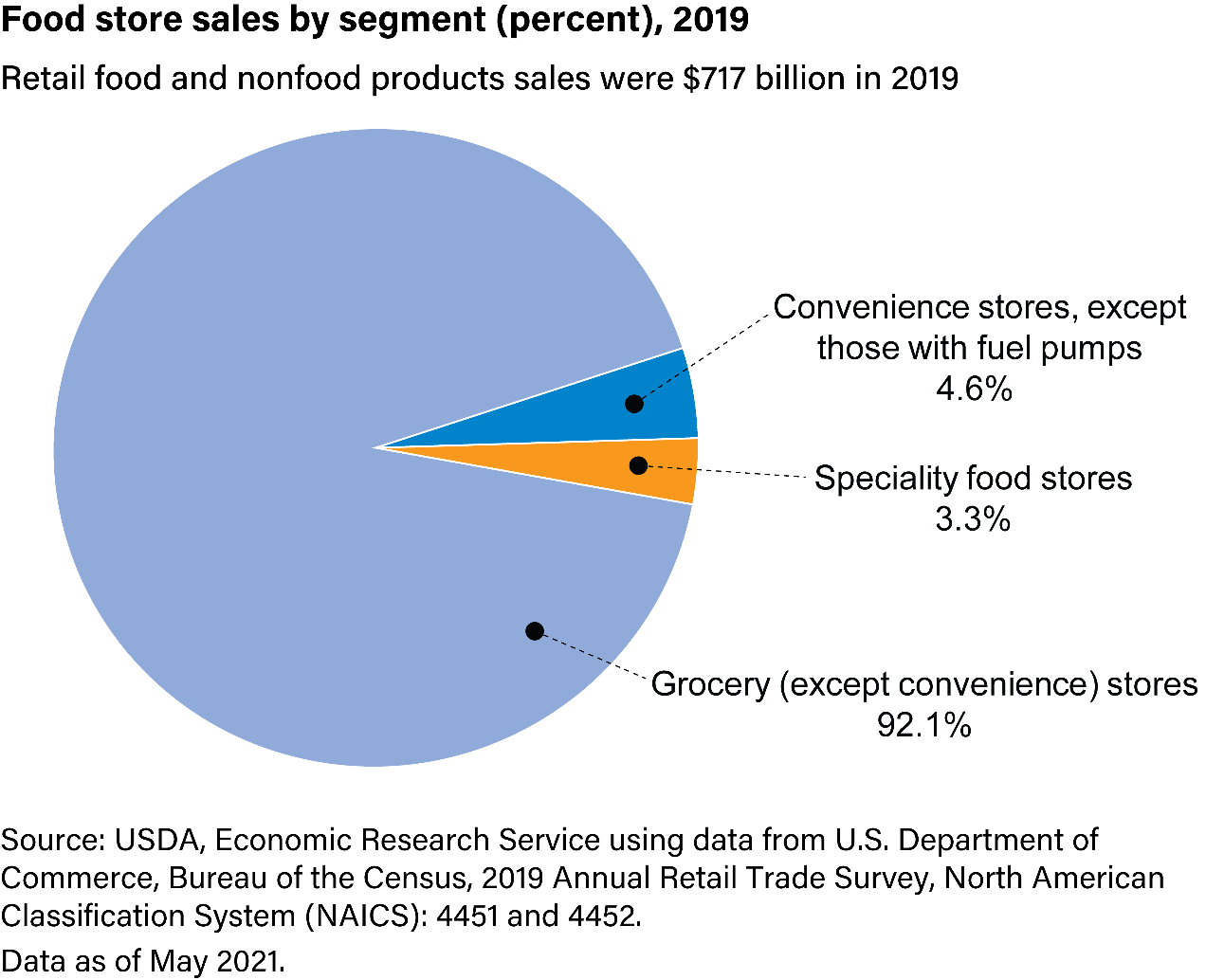

Yet there is little evidence that the U.S. grocery store market suffers from a troubling bout of anti-consumer concentration lining the pockets of profiteering corporations and their fat-cat CEOs. For starters, the latest data from the USDA show that there were a whopping 115,526 retail stores selling food in 2019 (the last year of data available). That’s about one store for every 1,000 U.S. households, the vast majority of which are traditional grocery stores:

The USDA adds that a handful of big grocery companies account for a significant portion of stores and sales, but the industry is hardly “concentrated” in any serious sense, with the top eight companies winning only about half of all U.S. grocery sales in 2019 (and only increasing about 10 percentage points over the last two decades):

As the above chart shows, moreover, the market really diversifies after that: The next 12 grocery companies had only another 10 percent of the market, and the remainder was occupied by all sorts of other grocery options.

And speaking of those options…

The pandemic undoubtedly changed the U.S. grocery picture since 2019, but not necessarily in Big Grocery’s favor. Most notably, many Americans were pushed into to shopping online for their groceries—at their preferred brick-and-mortar supermarkets, superstores like Target and Walmart (the largest grocer by sales), and at online only options—including not only established players like Amazon but a bunch of newcomers like Thrive Market, Fresh Direct, Shipt, and Boxed.

Indeed, a brand new national survey finds that Amazon ranked first and fifth in terms of overall grocery customer satisfaction (including price, digital options, quality, convenience, speed, operations, discounts, and rewards):

The survey results also show the variety of U.S. grocery options—with several “big box” retailers also making the list. (I love me some Costco produce and meat.) Back to e-commerce, the linked article notes that “digital’s share of grocery sales more than doubled” in recent years, and that Amazon received its top-ranking (for the second year) in a row because of its low prices.

Consumers win again!

Oft-maligned “dollar stores” have also gotten into the grocery game during the pandemic, adding to the list of “non-traditional” food retailers like drug stores and gas stations (both of which also are offering more “grocery-style” food options these days). And then, of course, there are the “mom and pop” specialty stores and farmers markets that provide even more choice and competition in many markets—the kinds of local alternatives that, along with the big national chains, have been shown to rebut broader “market concentration” allegations that look at only national-level data.

Indeed, it was just this type of thick, multifaceted competition that pushed many supermarkets into suppressing price increases over the last year—exactly the opposite of what Warren and the FTC appear to be claiming:

The grocery industry’s financials also provide little reason for concern—even during the pandemic. For example, supermarkets historically have some of the lowest net profit margins (sales revenue minus costs, expenses, and taxes, divided by total sales) of any industry in the United States, averaging about 2.2 percent per year going back a decade or more. This is because, as helpfully explained by former grocery store manager Jeff Campbell, grocery chains make their money by maximizing total sales (revenue) across multiple outlets, and taking a tiny sliver of profit per sale. The industry model is one literally designed not to “gouge” consumers.

Pandemic-related restaurant closures increased grocery store sales (and thus total—“gross”—profits) since 2020, but these companies also had higher costs—including brand new ones like extra cleaning or PPE (e.g., “free” masks at the entrances). In other words, big grocery corporations took in more money but also spent more money, so just looking at their total sales or even gross profits tells us very little about whether the industry suddenly decided to turn on the Greed Machine. The demagogues ignore all of this.

Accounting for these costs and increased sales reveals the emptiness of the recent attacks on Big Grocery. Per the latest industry-wide data from NYU’s Stern School of Business, for example, the “Retail (Grocery and Food)” industry’s latest net profit margins were actually lower (1.1 percent) than they were in the pre-pandemic surveys:

The NYU data also show that the grocery store industry actually has some of the lowest profit margins of any industry in the country—ranking 86th of the 96 industries surveyed. (As an aside, let’s also note that the 15 “food wholesaler” companies surveyed had an even lower net profit margin at only 0.69 percent, while “food processing” companies had higher net profits (8 percent), but that was actually down from about 12 percent in 2019.)

Kroger, the largest U.S. grocery store chain and target of Sen. Warren’s Twitter ire, enjoyed similar profit margins over the last several years, with its latest (third quarter 2021) hitting 1.52 percent and coming in just a smidge below its average* since 2009 (1.67 percent) and above its median (1.45 percent) over the same period. Kroger’s largest public competitor, Albertsons, hit all of 2.5 percent—above its average net profit but still hovering right around the industry’s historical standard.

These consistently low profit margins are a good indication that, far from being hyper-concentrated and ruled by greedy, price-gouging fat cats, the grocery business is one of the more competitive and consumer-friendly industries in the country. (Just ask literally any foreigner who visits here.) If it weren’t so competitive, we’d probably expect to see higher profit margins—compared to pre-pandemic trends and the margins of other industries. Indeed, profit margins were the primary evidence cited by the White House in its recent broadside against the meatpacking industry’s market concentration. (Those allegations are more complicated and raise plenty of their own concerns, but still …)

Indeed, the industry’s business model and competitiveness help to explain why, as discussed in previous newsletters on our increasing material abundance, grocery inflation and food prices in the United States have been tame for decades now—with growth even going negative a few years ago:

Look at all that monopolism and stuff!

Broader Lessons Abound

While the claim that Big Grocery has suddenly turned on its anti-consumer Greed Machine during the pandemic is pretty ridiculous, it does offer some broader lessons about inflation and the new “hipster antitrust movement.”

First, there is just some terrible economic thinking going on here. As I told your Morning Dispatch crew, the grocery store demagoguery—along with the broader claims that inflation is primarily due to greedy corporations exerting their market power in certain industries—reflects a pretty basic misunderstanding of inflation as a microeconomic (developments in individual markets) phenomenon as opposed to what it actually is—a primarily macroeconomic (determined in the aggregate) one. In this regard, I redirect your attention to this illuminating Twitter thread from Harvard’s Jason Furman, in which he explains how—absent some increase in aggregate demand like fiscal stimulus or expansionary monetary policy—rising prices in one sector (say, groceries) would simply lead to lower prices in another sector (say, automobiles) and thus keep overall inflation steady because consumers would have fewer dollars to spend on the latter after paying for the former. That’s decidedly not what’s been happening over the last year or so: Prices are increasing across a variety of goods and services, with early spikes in some industries often replaced by others in subsequent months. There’s just no way “greed” in any one sector can explain it, as economist John Cochrane just explained in a new paper:

Much analysis misses the difference between relative prices and inflation, in which all prices and wages rise together. A supply shock makes one good more expensive than others. Only demand makes all goods rise together. There wouldn’t be “supply chain” problems if people were not trying to buy things like mad! A shift in demand from services to durables can make durable prices go up. But it would make services prices go down. And let us not even go down the ridiculous path of blaming inflation on a sudden contagious outbreak of “greed” and “collusion” by businesses from oil companies to turkey farmers, needing the administration to send the FTC out to investigate.

Yet even if we accept that higher prices since early 2019 are primarily supply-side problem (as opposed to a demand-side one driven by stimulus), the “concentration” theory suffers from two other flaws: timing (why did these long-dominant firms just start hiking prices now?) and composition (why are all sorts of other things—like used cars and furniture—also increasing at a similar rate?). Indeed, a quick look at the latest CPI figures show quite plainly that food prices are in no way outliers and, in fact, are slightly under trend over the last year:

The sizes of the bubbles above also show quite plainly that groceries (“food at home”) are of only modest importance to the overall CPI number (about 7.7 percent of the total).

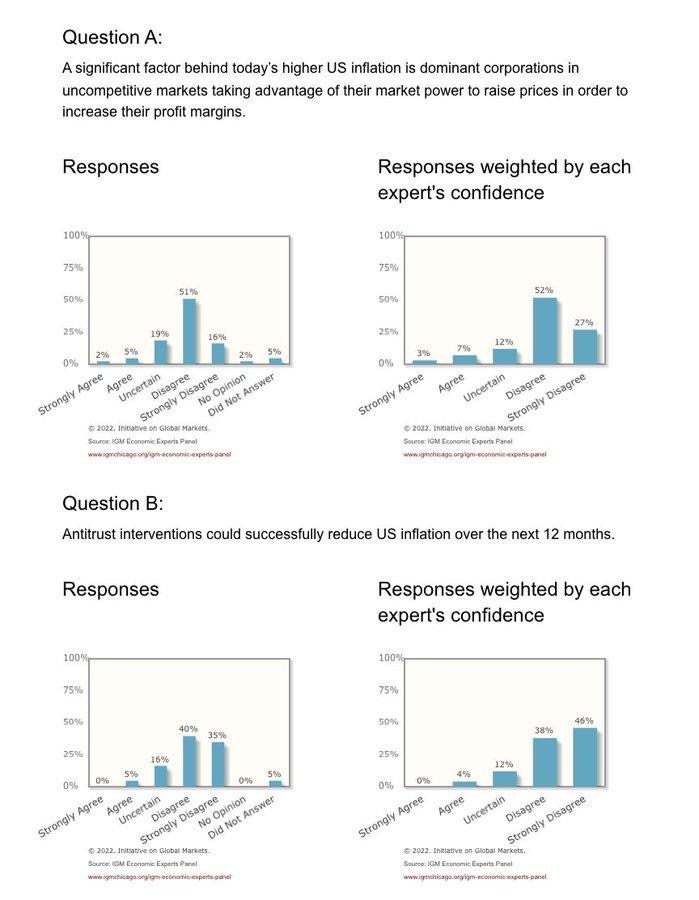

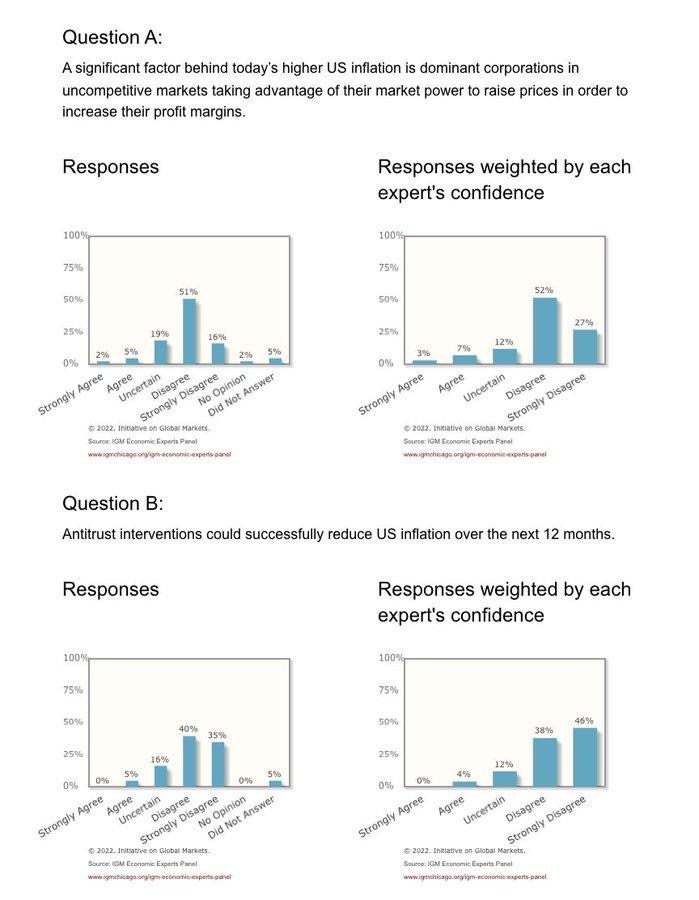

It’s these basic economic principles and accompanying data that explain why, in a recent IGM Chicago survey of leading economists, the vast majority of respondents disagreed with the claims that “dominant corporations” were a “significant factor behind today’s higher US inflation” or that antitrust interventions could reduce inflation:

As several of the respondents note in the comments, rising industry concentration might cause high food price levels, but it can’t possibly explain increasing food prices right now—especially in the face of years of pre-pandemic price moderation. It just makes no sense.

Second, the grocery store stuff reveals just how much of a problematic mess “hipster antitrust” really is. For example, the article up top notes that one goal of the FTC’s action to reduce corporate concentration in the U.S. grocery market MAY be to help smaller “local and regional” players (and presumably boost their U.S. market share). Yet doing that would probably harm American consumers by raising prices—precisely the opposite of what Warren and others worried about “food inflation” presumably want! As Campbell and others have explained, big grocery chains have kept U.S. food prices so low by being big and lean: With hundreds of stores, they can get quantity-based discounts from major suppliers and spread out corporate administrative costs across the entire company. They also feature more packaged items to avoid spoilage and keep labor costs lower, and typically lack the bells and whistles that upscale grocers (e.g., Whole Foods) and specialty shops feature. Sure, that means a less exciting customer experience, but it also means much lower prices and higher consumer satisfaction overall—as the survey above shows. It also surely doesn’t stop us from frequenting both the big guys and the smaller ones, as the market is segmented into two distinct, but complementary ones: cheap bulk stuff and pricier specialty items (as my own local/Whole Foods, Food Lion, and Costco receipts can attest).

That Warren, the FTC, and others would target, contra all the evidence, grocery stores for antitrust scrutiny also reveals just how susceptible the law is to politicization now that it’s untethered from the simple and objective “consumer welfare” standard that guided antitrust for decades. Indeed, just as these newfound “inflation hawks” bash Big Grocery, they ignore all of the other U.S. policies—steel and lumber tariffs, sugar quotas, immigration restrictions, etc.—that actually do raise prices, hurt consumers, and likely increase market concentration. (Tariff-protected steel actually saw much higher prices and profits last year, yet nobody seems to care about domestic producers’ longstanding anti-consumer stranglehold on the U.S. market!) Removing these microeconomic impediments probably wouldn’t dampen overall inflation much, but it would lead to lower prices in the deregulated industries. Yet none of the grocery demagogues seem to care.

If the feds can brush these policies/industries aside and instead go after the American grocery market—a low-margin, dynamic, diverse world of low prices and global abundance!—when political necessity demands it, what can’t they go after?!

(Spoiler: Nothing.)

Chart(s) of the Week

Bonus Chart of the Week

The Links

*Correction, January 20: This piece initially misstated Kroger’s profit margin for the third quarter of 2021. It was 1.52 percent, not 1.67.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.