Dear Capitolisters,

In case you haven’t noticed, “greedflation” is having quite the moment. In just the last couple months, several major media outlets have promoted—sometimes repeatedly—the formerly “fringe” idea that corporate profiteering, not supply and demand, are to blame for our current inflationary moment. As these stories detail, a small cadre of academics and policymakers allege that companies with price-setting market power have seized on supply chain problems, the Ukraine invasion, and other newsworthy economic disruptions to justify prices increases that far exceed their own heightened labor and input costs, thus boosting profit margins and “heighten[ing] inflationary pressures” for the U.S. economy overall. When this idea first arose, I—like a lot of other people, it seems—dismissed it as a momentary fad. But since the “greedflation” concept has not just stuck around but actually accelerated, it warrants more discussion.

That doesn’t mean, however, that it’s any less wrong.

‘Greedflation’ Isn’t New

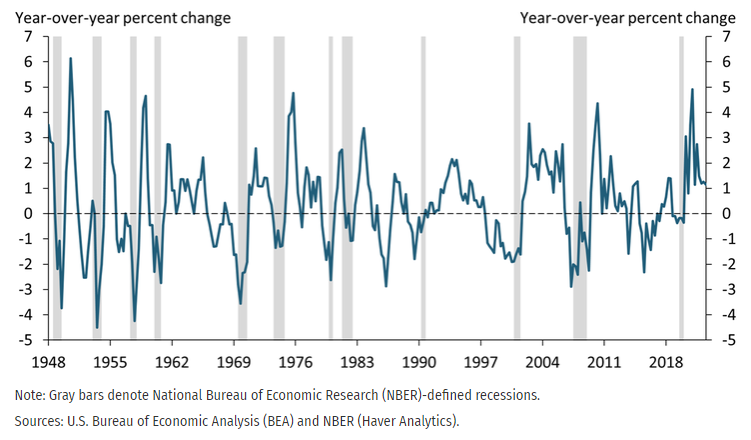

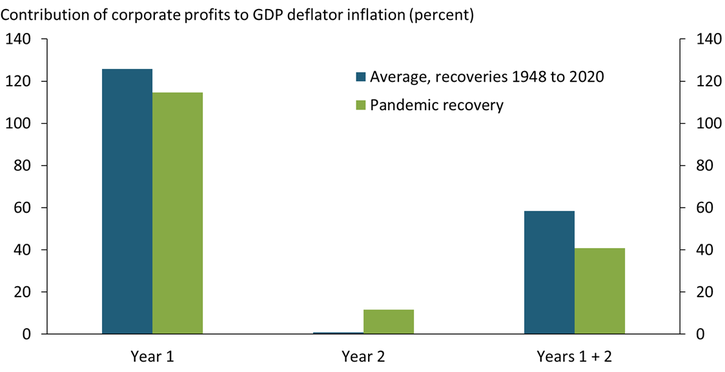

For starters, there’s nothing really novel about corporations raising prices after a recession and thereby enjoying a temporary boost in profits. As just documented by the Kansas City Federal Reserve, for example, companies during and after a recession routinely engage in “anticipatory price-setting, in which firms expect higher costs of production in the near future and thus raise prices on the goods they produce today.” Because costs incurred during a recession are “temporarily depressed,” higher prices produce a temporary surge of profits, which then start to decline as an economic recovery takes hold and input costs rise. The report finds this pattern of profits in every U.S. recession going back to 1948 and finds it again in the pandemic recession, with a similar magnitude.

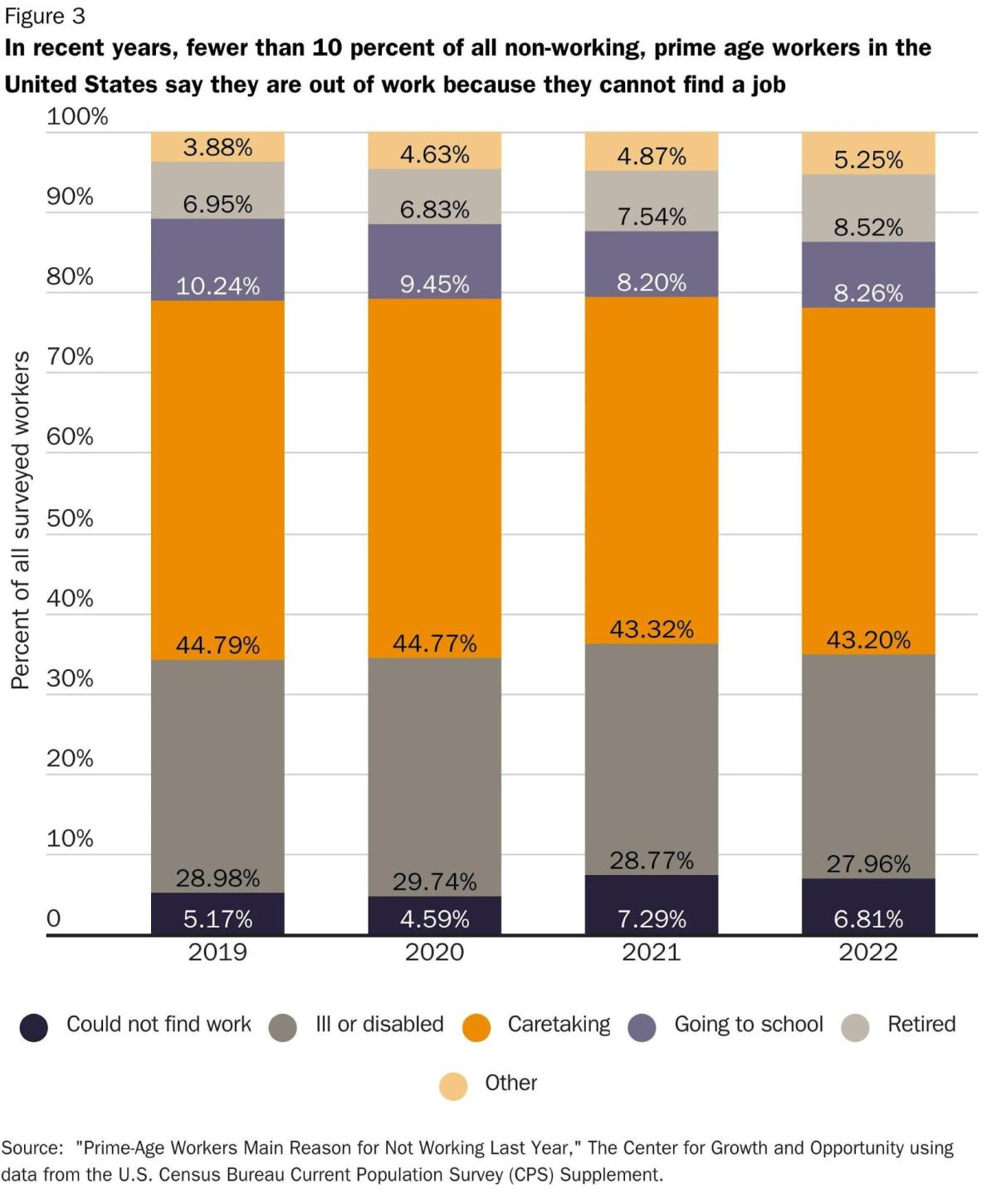

In fact, as shown in figure 3 below, corporate greed—erm, profit—was actually a little lower during the 2021-2022 pandemic recovery than in previous recoveries:

So much for a sudden and novel burst of “greedflation,” huh?

‘Greedflation’ Ignores Consumers Entirely

This historical perspective is useful, but it avoids more important and fundamental points about higher prices and corporate profits during and after the pandemic: Profit-maximizing firms could only raise prices (and earn higher profits) because consumers let them; consumers let them because they were flush with cash; and consumers were flush with cash mainly because of government policy.

The role that consumers play in companies’ pricing decisions isn’t exactly groundbreaking stuff; it’s a standard part of mainstream microeconomics and frequently mentioned in economic analyses and business reporting—even for essentials like food. For example, a Kansas City Fed report from late last year found that consumer spending and behavior (eating more at home, and then shifting back)—not corporate profiteering—were the primary drivers of higher U.S. food prices during the post-pandemic recovery.

In the business press, meanwhile, consumer demand and its role in corporate pricing decisions is a frequent topic. The New York Times in April, for example, reported that multinational food producers and retailers like Unilever, PepsiCo, and McDonald’s had increased prices and earned higher profits over the last couple years but were recently starting to see more resistance from consumers that would decrease future sales and temper further price increases—resistance that wasn’t there earlier in the recovery. A couple months earlier, major beer producers reported much the same thing: According to the CEO of Constellation brands (Corona and Modelo), “prices have gone as far as consumers will tolerate” in California, while nationally “the company will need to be more cautious about raising prices further since consumers are starting to balk.” Meanwhile, CNBC reported that major grocery chains were rapidly rolling out cheaper private label brands because consumers in 2023 were becoming more cost-conscious than they’d been in the two years prior. “Businesses do respond to shoppers,” economist Mark Zandi told CNBC, “If consumers are price-conscious, price-sensitive, that’ll go a long way to convincing businesspeople to stop raising prices and maybe even provide a discount.”

Crazy, I know.

The same dynamics apply beyond food (if not more so), and for the biggest companies. The Wall Street Journal reported late last year, for example, that Walmart, Target, Amazon, and other retail giants were “canceling orders, resisting price increases and in some cases asking suppliers to provide discounts” because of “shifting consumer demand” (which caused inventories to swell) and the retailers’ desire to “attract cash-strapped shoppers.” And even some of the articles that take the greedflation narrative seriously hint at consumers’ role in price-setting. Just this week, for example, the Times’ latest greedflation piece mentions that “[c]ustomers have grumbled, but they have largely kept buying.” The Journal’s piece, meanwhile, humorously noted that “One puzzle is why consumers have played ball.”

This is not, actually, much of a “puzzle” at all: American consumers have “played ball” because they have the money to do so—lots of it. The aforementioned Kansas City Fed paper gets at this when examining why beef prices shot up in recent years, padding Big Meat’s profits along the way: “Although personal income typically declines during recessions, putting downward pressure on meat consumption, household income actually rose during the pandemic-induced recession. So, too, did household consumption of meat (among other products), putting upward pressure on food prices” (emphasis mine). Thus, contrary to the spin from the White House and others, U.S. meat prices didn’t rise because of some sort of Big Meat pricing conspiracy; they rose because suddenly cash-rich consumers wanted to buy more meat.

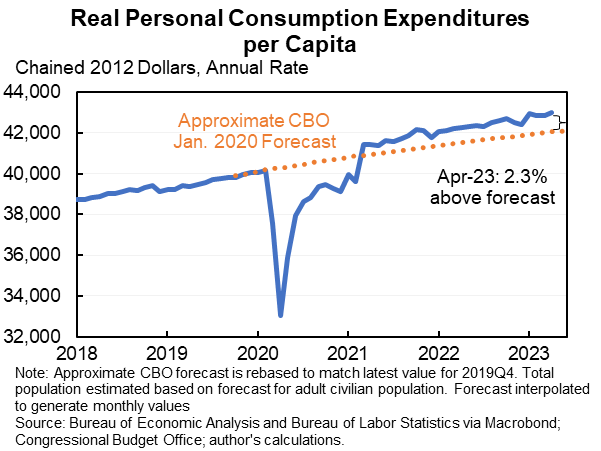

The aggregate economic data clearly show our national spending spree—both during and after the pandemic. Harvard’s Jason Furman, for example, calculates that Americans’ spending (personal consumption expenditures or PCE) has been well above trend since early 2021, even after accounting for inflation:

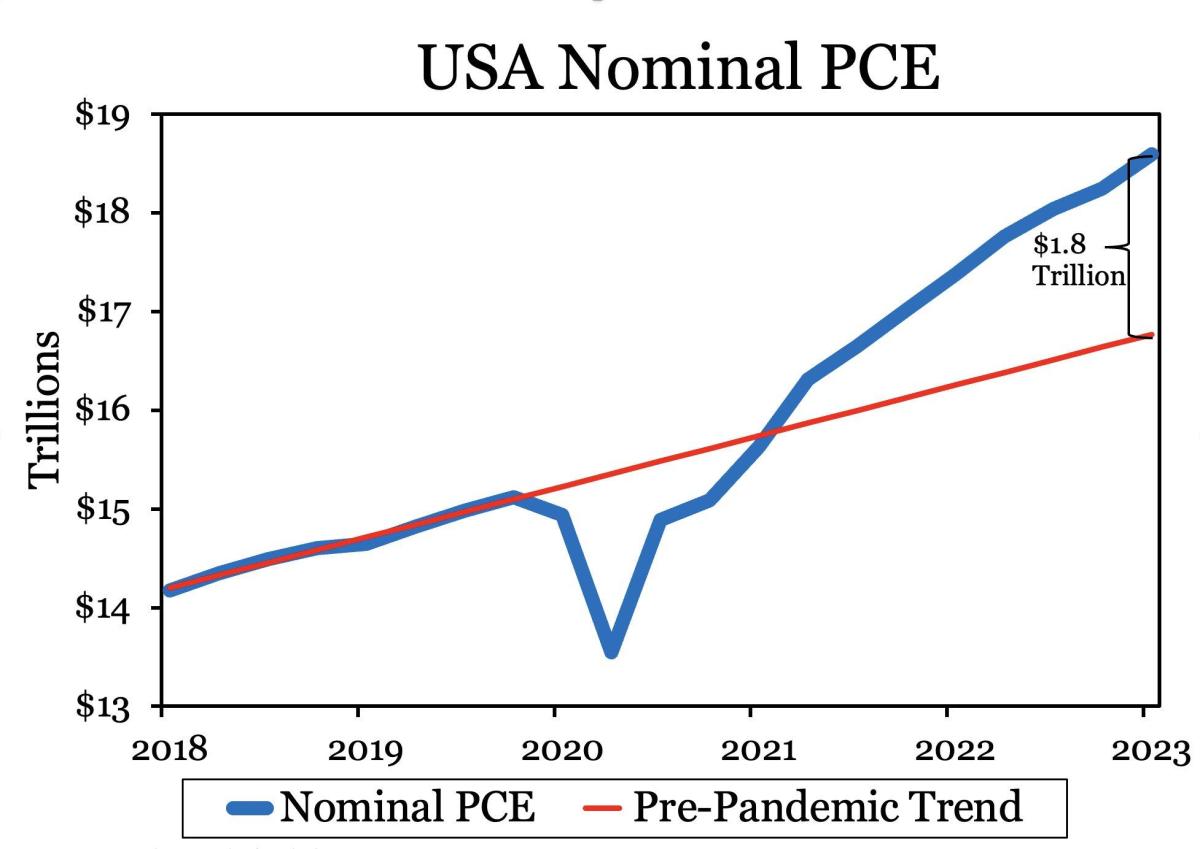

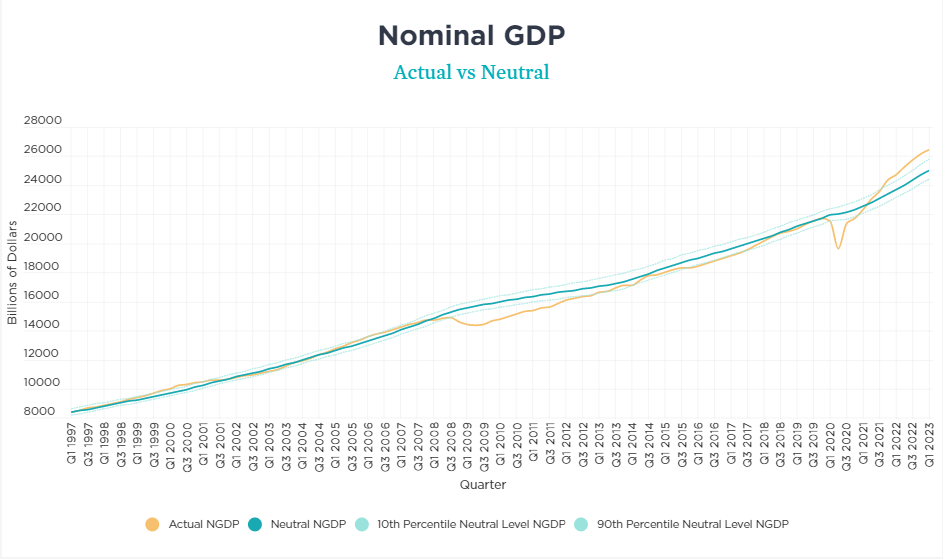

The nominal (not-inflation-adjusted) figure, as the Mercatus Center’s David Beckworth shows, is even more dramatic:

Beckworth rightly notes this chart should accompany any and every discussion of “greedflation,” because “those profits do not happen unless we get this surge in nominal demand growth.”

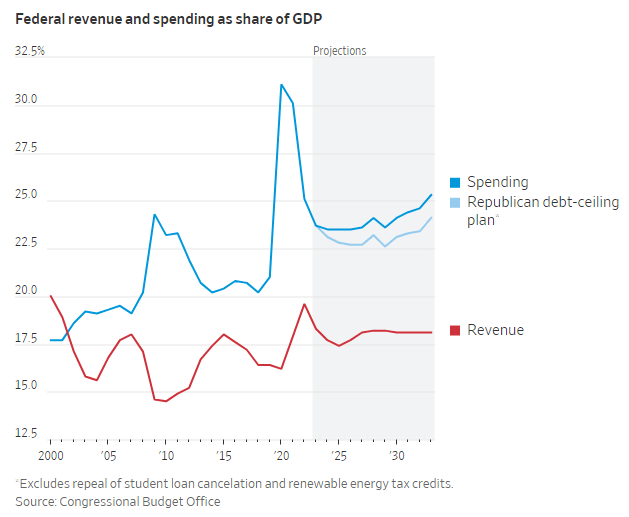

The main drivers of that surge in demand (spending) are similarly unsurprising and well-understood today: highly expansionary U.S. fiscal and monetary policy enacted during 2020 and 2021. On the fiscal side, federal spending as a share of GDP skyrocketed in 2020, and will remain elevated—even after the current debt limit deal is enacted.

This spending was not, however, just about cutting checks to Americans during the pandemic. New research shows, for example, that federal aid to states during the pandemic was way too generous, thus resulting in “a range of targeted tax cuts and spending measures” at the state-level and “adding to inflationary pressure.” Federal pandemic-era policy also induced consumer spending in other ways. Thanks to the student loan debt moratorium, for example, “borrowers used the new liquidity to increase borrowing on credit cards, mortgages, and auto loans rather than avoid delinquencies.” As we’ve discussed previously, many other state and federal programs provided similar forms of temporary debt relief, giving Americans more money to spend at that time and—as we’ll discuss in a second—in the future.

Given this massive fiscal jolt, numerous academic analyses have found—per my Cato colleague Norbert Michel—that “the inflation problem we’re experiencing was indeed fiscally induced, though “perhaps the Fed could have been less accommodative of Congress’s fiscal spending, and it surely could have started tightening a bit sooner.” Other studies show much the same. As the Journal’s Greg Ip admitted earlier this month, “in retrospect, fiscal policy overdid it.”

(Ya think?)

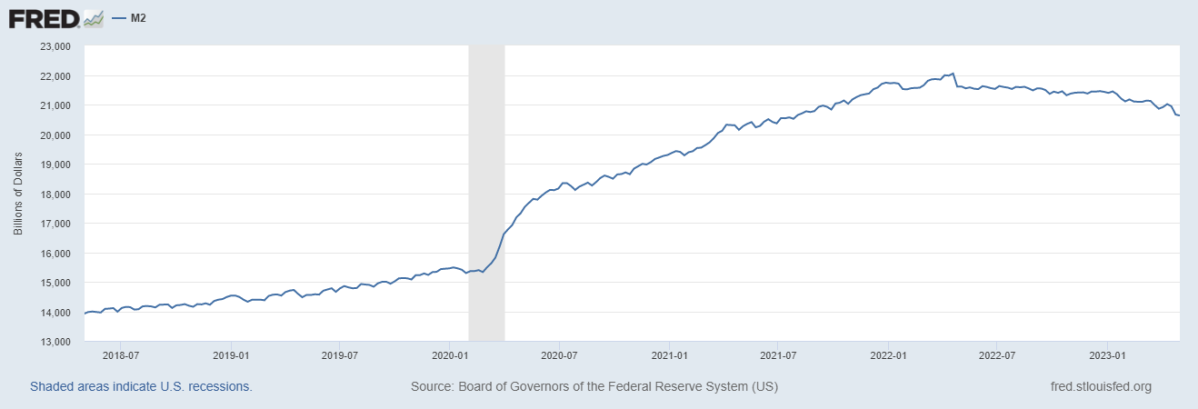

Speaking of Fed policy, it too was highly expansionary over the same period, further encouraging Americans consumption (via mortgages, car loans, etc.). Here, for example, is the spike in the money supply (M2) during 2020-21:

Comparing total economic output (nominal gross domestic product) versus a “neutral” benchmark growth rate also indicates that monetary policy has been very expansionary since early 2021 and, at least through Q1 2023, continues to be that way:

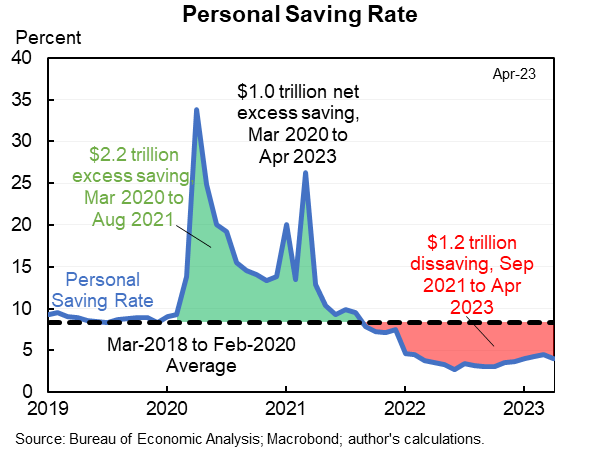

Fiscal and monetary expansion has waned in recent months, but Americans are still spending at elevated levels because, as Furman shows, they’re using the savings they built up during the pandemic when government support was so generous:

Economist Joey Politano thus provides a good rundown of where things now stand and how we got there (emphasis mine):

At the start of the pandemic, Americans accumulated trillions of dollars in excess savings—workers dramatically cut back on their consumption, households received generous relief payments from the Federal government, and borrowers refinanced their debt at newly-lowered interest rates, so people were earning significantly more in aggregate than they were spending. The end result was more than $2T in total savings above what would be expected in a hypothetical no-pandemic world, with the bulk of those assets concentrated among high earners. However, by 2022 the script had completely flipped—Americans were spending much more than they would normally, drawing down on their excess savings, and re-engaging in debt amidst a consumption boom partially caused by and partially enabling ongoing inflation. Today, most of those excess savings have been spent down, with households only having an extra $750B remaining (or about $650B accounting for inflation).

In short, you can debate whether highly expansionary U.S. fiscal and monetary policy was the right way to quickly escape the pandemic recession, but you can’t ignore it—and its obvious effects—altogether. “Greedflation” seemingly does just that.

As Beckworth put it to the New York Times this week, “Many telling the profit [greedflation] story forget that households have to actually spend money for the story to hold. And once you look at the huge surge in spending, it becomes inescapable to me where the causality lies." Indeed.

‘Greedflation’ Forgets What Inflation Actually Is

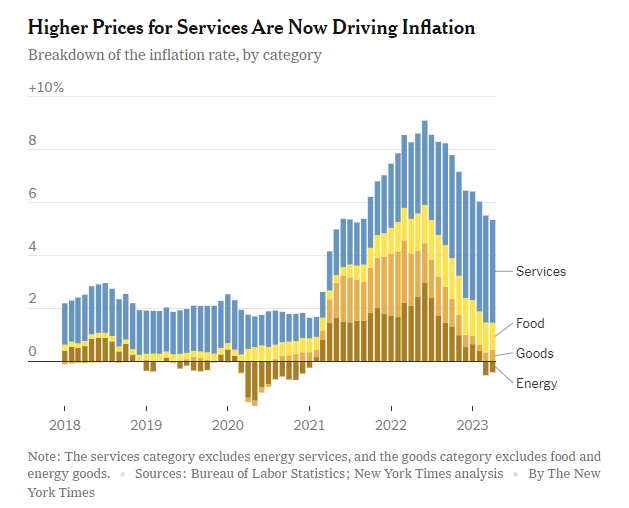

Other facts further confound the greedflation story. For starters, inflationary pressures have shifted a lot between 2021 and today, moving from goods to services:

As Furman recently noted on Twitter, the greedflation thesis requires us to believe that goods companies had (and abused) market power in 2021-22 but then passed the baton to totally different services companies in totally different industries sometime last year. That is some seriously impressive, economy-wide collusion!

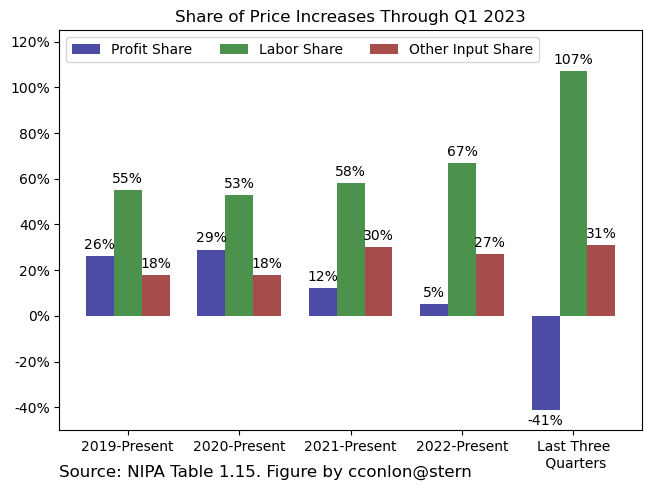

Also, as several folks have recently noted, corporate profits are now falling and have been for three straight quarters (two if you exclude financial companies), even as inflation has persisted.

Even sectors with relatively high levels of concentration, such as meatpacking and shipping, have seen their profits drop in recent months. Did all these companies—including ones with “market power”—suddenly stop getting greedy?

C’mon, man.

In general, all of this stuff seems to reflect a fundamental misunderstanding about what “inflation” really is—an increase in the general price level, as opposed to, say, a nefarious exercise in discrete pricing power by a handful of companies or industries, even highly concentrated ones. Akiva Malamet put this well in a column last year:

While a corporation might have a great deal of market power, it cannot affect the entire Consumer Price Index. Inflation is also unrelated to corporate concentration. Further, prices reflect decisions by a multitude of sellers with competing interests. Sellers are too numerous to collude and fix prices, because transaction costs rise as the number of colluding actors increases. The number of people who would need to be aware of each other, meet, and agree on a price is huge. Further, price-fixing agreements tend to break down due to defectors trying to beat out the competition by lowering their prices against the majority.

More generally, prices do not result from the will of specific actors. Prices are emergent products of supply and demand. They reflect the myriad decisions of producers and consumers with a variety of preferences and differing opportunity costs. Inflation (a general rise in the price level) tends to derive from an excess amount of liquid currency available, relative to the amount of real goods and services being produced at a given moment. In simple terms, inflation is a problem of “too much money chasing too few goods”.

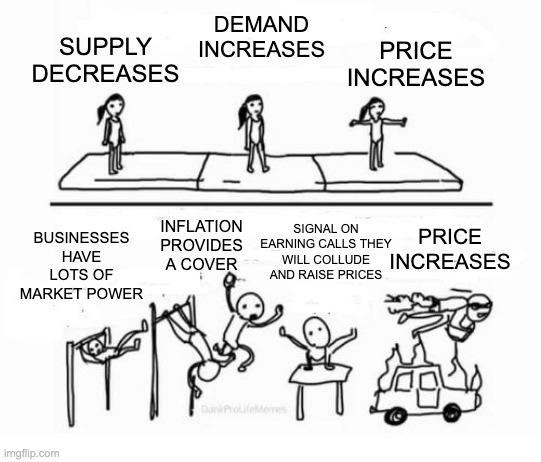

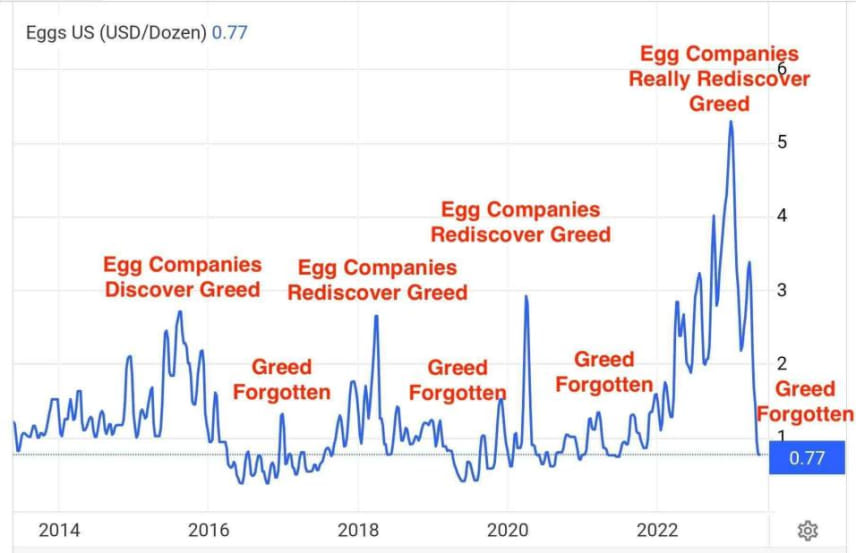

The charts above reinforce this simple lesson, and forgetting it produces a host of absurdities. As my Cato colleague Ryan Bourne pointed out in a recent column, for example, the Greedflation World requires corporations to somehow shift, en masse, from generous to “greedy” and back again over the course of a few years. (See the Charts of the Week for how this apparently worked for Big Egg.) It requires one company’s price increases to somehow not lead to lower-cost rivals gaining any market share. And, perhaps most damningly, it requires price increases by companies with supposed “market power” to somehow not leave consumers with less money to spend elsewhere in the economy (because that would reduce price pressures for other goods and services and thus keep inflation tame overall). Greedflation demands we believe in these and other mysterious tales, while handwaving away not only the economics textbooks but also very clear data on national supply and demand since 2020.

Or, if you prefer your mental gymnastics in meme form, economist Bryan Albrecht has you covered:

As Bourne rightly notes, “Corporate greed primarily affects relative goods’ prices, not the overall price level and inflation. Loose money driving excess spending does that.”

It’s a simple point. It’d be nice if the media remembered it.

Chart of the Week

Greedflation watch:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.