If I had to put a name on this era of right-wing Christian politics, it would be “The Great Rationalization.” As the right has become more cruel, malicious, and dismissive of character, some Christian thinkers have been willing not just to excuse this transformation but to affirm it as deeply virtuous.

Drill down into any of these rationalizations, and you’ll find the same theme repeated time and again: Desperate times call for desperate measures. Those who don’t understand the present crisis or the necessity of changed tactics are simply not men for the moment.

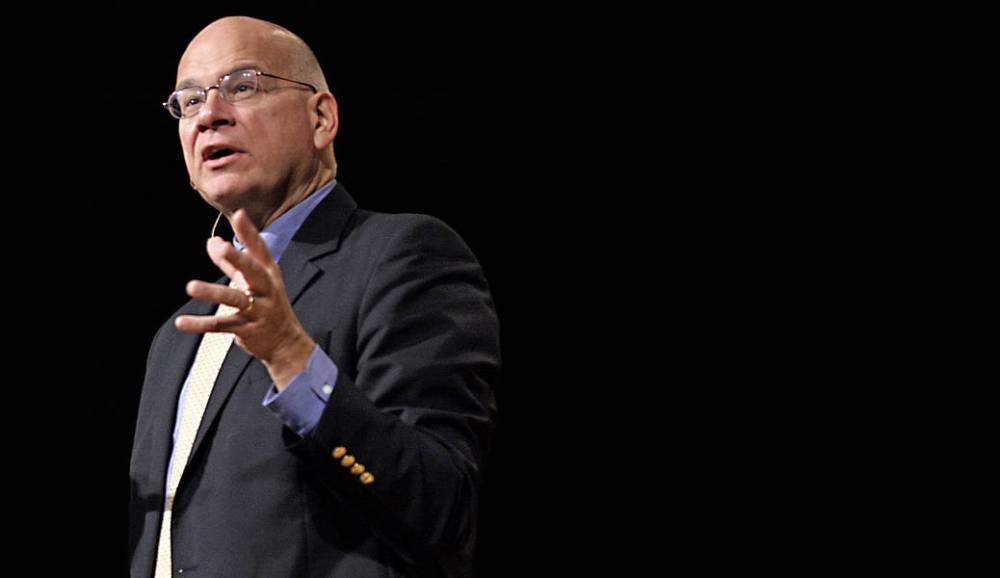

A good example of the genre was published this week in First Things. The piece is called “How I Evolved on Tim Keller,” and its author, First Things associate editor James Wood, makes all the familiar arguments, though more civilly than most. Wood takes pains to compliment and note Keller’s immense and positive influence on him personally and on the church collectively (he calls him a “C.S. Lewis for the postmodern world”), but he goes on to inform us that he has “turned elsewhere for guidance in our contemporary political moment.”

In short, it’s because my friend Tim shuns political tribalism (emphasizing a “third way” between red and blue) and strives, in Wood’s words, to be “‘winsome,’ missional, and ‘gospel-centered’” in his approach. Wood says that Tim recognizes “though the gospel is unavoidably offensive, we must work hard to make sure people are offended by the gospel itself rather than our personal, cultural, and political derivations.”

Why is this a problem? You guessed it. Times have changed. And after 2016 Wood evolved:

At that point, I began to observe that our politics and culture had changed. I began to feel differently about our surrounding secular culture, and noticed that its attitude toward Christianity was not what it once had been. Aaron Renn’s account represents well my thinking and the thinking of many: There was a “neutral world” roughly between 1994–2014 in which traditional Christianity was neither broadly supported nor opposed by the surrounding culture, but rather was viewed as an eccentric lifestyle option among many. However, that time is over. Now we live in the “negative world,” in which, according to Renn, Christian morality is expressly repudiated and traditional Christian views are perceived as undermining the social good. As I observed the attitude of our surrounding culture change, I was no longer so confident that the evangelistic framework I had gleaned from Keller would provide sufficient guidance for the cultural and political moment. A lot of former fanboys like me are coming to similar conclusions. The evangelistic desire to minimize offense to gain a hearing for the gospel can obscure what our political moment requires.

Wood claims Keller’s approach was “perfectly suited” for the so-called “neutral world,” but the “‘negative world’ is a different place.” Wood says, “Tough choices are increasingly before us, offense is unavoidable, and sides will need to be taken on very important issues.”

There are so many things to say in response to this argument, but let’s begin with the premise that we’ve transitioned from a “neutral world” to a “negative world.” As someone who attended law school in the early 1990s and lived in deep blue America for most of this alleged “neutral” period, the premise seems flawed. The world didn’t feel “neutral” to me when I was shouted down in class, or when I was told by classmates to “die” for my pro-life views.

Nor was the world “neutral” for Tim. Last night he tweeted about his experience launching Redeemer church in New York:

And if you want empirical evidence that New York City wasn’t “neutral” before 2014, there was almost 20 years of litigation over the city’s discriminatory policy denying the use of empty public school facilities for worship services. The policy existed until it was finally reversed by Mayor Bill de Blasio in 2015.

Even growing up in the rural south, I wasn’t surrounded by devout Christianity, but instead by drugs, alcohol, and a level of sexual promiscuity far beyond what we see among young people today. Where was this idealized past? There may have been less “woke capital,” but there was more crime, more divorce, and much, much more abortion.

Moreover, this was happening at a time when Christians’ free speech and religious liberty rights were far less well-established. Speech codes reigned, and in the first 15 years of my legal practice hundreds of Christian student groups faced expulsion from campus. In response, Christians “took sides” on the very important issues of life and religious liberty and not only dramatically transformed First Amendment jurisprudence, the pro-life movement helped dramatically reduce abortion rates until the point where abortion is less common than before Roe.

That’s not to say that the world was worse and is now getting better. It’s to say that the narrative of cultural decline is not nearly so simple. The First Amendment is more potent than it’s ever been, yet cancel culture on the right and left are evidence of a cultural retreat from free speech. Declines in divorce, abortion, teen sex, and single-parenting indicate a turn towards more traditional lifestyle choices (including in elite cultural spaces), yet the controversy over transgender athletes indicates that the definition of “man” and “woman” is now subject to furious debate.

This complexity applies even to the documented, increasing hostility between America’s competing political tribes. After all, increasing partisan animosity is unquestionably mutual. “They” hate “us”? Well, “we” hate “them” just as much. When it comes to negative partisanship, neither side has clean hands. If we truly live in a “negative world,” then Christians helped make it negative.

And because of the partisan press and social media, we’re much more cognizant of each and every outrage and offense than we ever were before. We’re constantly (and intentionally) “revved up” by voices who are invested in teaching us that the end is near and America is on the precipice of extinction. How do we know we’re being artificially “revved up”? The data indicates Americans are simply wrong about their political opponents. We tend to believe they’re more extreme than they really are.

It’s important to be clear-eyed about the past because false narratives can present Christians with powerful temptations. The doom narrative is a poor fit for an Evangelical church that is among the most wealthy and powerful Christian communities (and among the most wealthy and powerful political movements) in the entire history of the world.

Yet even if the desperate times narrative were true, the desperate measures rationalization suffers from profound moral defects. The biblical call to Christians to love your enemies, to bless those who curse you, and to exhibit the fruit of the spirit—love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control—does not represent a set of tactics to be abandoned when times are tough but rather a set of eternal moral principles to be applied even in the face of extreme adversity.

Moreover, Christ and the apostles issued their commands to Christians at a time when Christians faced the very definition of a “negative world.” We face tweetings. They faced beatings.

As a notable piece of evidence of our “negative world,” Wood points to Princeton Theological Seminary rescinding its decision to award Tim its “Kuyper Prize for Excellence in Reformed Theology and Public Witness.” (The seminary rescinded the award, but Tim still delivered a lecture.)

Imagine trying to even explain this to an apostle. “There’s this famous and influential Christian pastor, and . . .” Paul would stop you right there. That very idea would be novel to him, as would the idea that revoking a prize but delivering a lecture would be evidence of any kind of crisis requiring one to change a “winsome, missional, and gospel-centered” approach to the public square.

Paul called Christians to exhibit the fruit of the spirit even when they were being nailed to crosses and clawed by lions. Peter called on Christians to give a defense of their faith with “gentleness and reverence” even when they “suffer for righteousness.”

Sadly, this moral analysis is alien to all too many politically engaged Christians. They approach political contests differently from the way they approach their families or even their businesses. They apply an instrumentalist lens that they don’t apply to other areas of life. Is honesty an imperative in business only so long as it “works” to generate a profit or to maintain your employment? Is fidelity an imperative in marriage only so long as it “works” to provide the sense of happiness and sexual fulfillment you believe your entitled to?

No, any decently discipled Christian knows that in these vital areas of life, the means are the ends. Even under financial duress or in struggling marriages, Christians maintain honesty and fidelity not because they “work,” but because they’re obeying and glorifying God.

But in politics? If we reject lies and liars we might lose, and we believe we cannot lose. If we maintain basic commitments to Christian character we might lose, and we believe we cannot lose.

Yet in all of life the command to act justly is inseparable from commands to love kindness or to walk humbly. And the spirit of fear that grips so much of the modern American church might be a reason why so many Christians have scorned civility and decency in the public square, but it is not a justification.

It is also clear that Wood (and many others) simply misunderstand Keller’s “third way” approach to politics. Wood says that “it encourages in its adherents a pietistic impulse to keep one’s hands clean, stay above the fray, and at a distance from imperfect options for addressing complex social and political issues.” But this is wrong. Keller isn’t arguing for disengagement. He’s arguing for a commitment to biblical justice, and that both red and blue suffer from profound flaws:

Another reason Christians these days cannot allow the church to be fully identified with any particular party is the problem of what the British ethicist James Mumford calls “package-deal ethics.” Increasingly, political parties insist that you cannot work on one issue with them if you don’t embrace all of their approved positions.

This emphasis on package deals puts pressure on Christians in politics. For example, following both the Bible and the early church, Christians should be committed to racial justice and the poor, but also to the understanding that sex is only for marriage and for nurturing family. One of those views seems liberal and the other looks oppressively conservative. The historical Christian positions on social issues do not fit into contemporary political alignments.

I have found this to be true. In the past week I’ve written strongly against Roe and in support of Justice Alito’s leaked draft opinion in the pages of The Atlantic, and you should read my inbox. In the past month, I’ve urged Christians to reject the idea that the fight over critical race theory is a religious war—in part because it closes our minds to thoughtful Christian critiques of the church—and you should read my inbox.

“Above the fray”? No, not even close. To be committed to biblical justice while also rejecting political partisanship doesn’t put you out of the fight. It instead subjects you to periodic gang-tackling, from both sides of the field.

Finally, it’s important to recognize that the “third way” approach represents the humble recognition that Christians can in good conscience (and consistent with orthodox Christian theology) reach different positions on the political spectrum—in part because the answers to America’s social problems are not only hard, they’re extremely complicated.

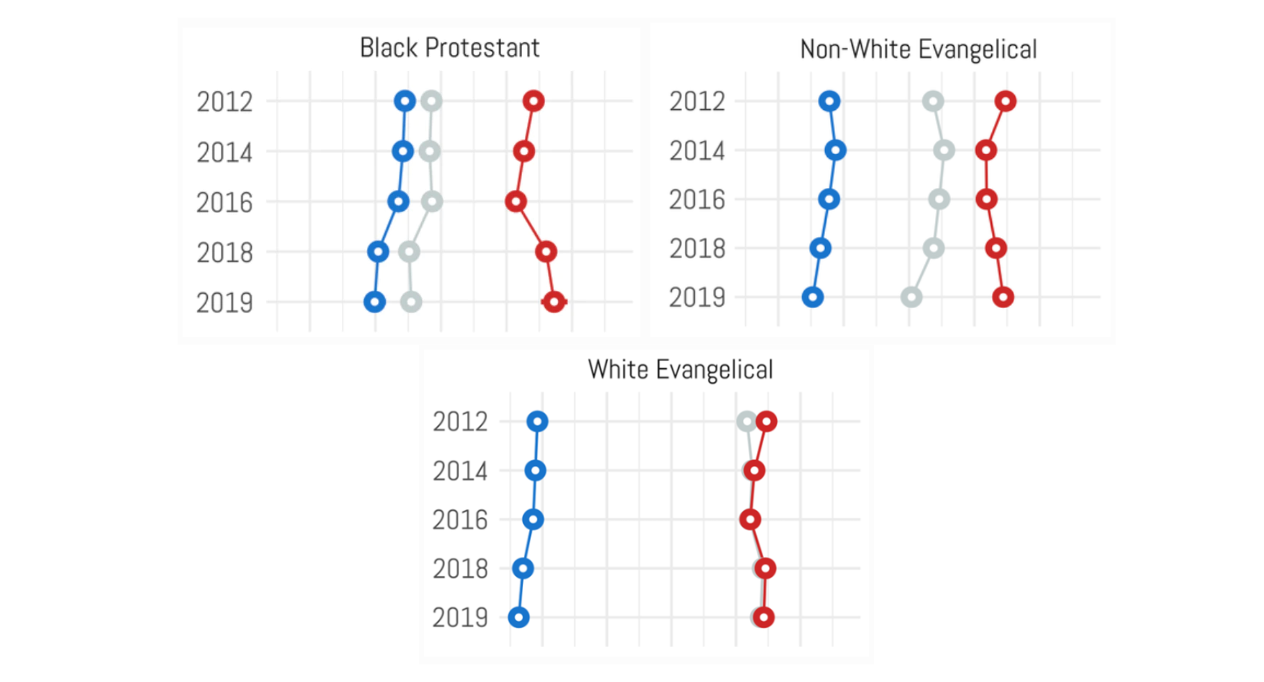

I’m going to show you three charts which demonstrate where members of different American faith groups place themselves relative to the political parties. They were asked to “place yourself, Democrats, and Republicans in ideological space.” As you can see, Black Protestants see themselves as slightly to the right of Democrats, nonwhite Evangelicals see themselves in the middle, and white Evangelicals see themselves as identical to Republicans:

The fact that so many millions of believers—people who diligently study the scripture and have deep, orthodox Christian faith themselves—come to competing answers about hard questions isn’t a reason to refuse to take a position. The command to “act justly” remains. But it should reaffirm the necessity of “walking humbly.”

Tim has been ministering in New York City for decades. That means he has much more up-close interaction with diverse Christian communities than, say, your typical suburban or rural Evangelical pastor. Prolonged exposure to differing Christian views on contentious issues is and should be a profoundly humbling experience. It constantly reminds you that we “see through a glass darkly” and that our confidence in our own reasoning and ideas is often misplaced.

We live in an age of negative polarization, when the cardinal characteristic of partisanship is personal animosity. In these circumstances, a Christian community characterized by the fruit of the spirit should be a burst of cultural light, a counterculture that utterly contradicts the fury of the times. Instead, Christian voices ask that we yield to that fury, and that a “negative world” is now no place for the “winsome, missional, and gospel-centered approach.”

But this isn’t an evolution from Tim Keller, it’s a devolution, and it’s one that’s enabling an enormous amount of Christian cruelty and Christian malice. Wood says “Keller was the right man for a moment,” but he also says, “it appears that moment has passed.” That’s fundamentally wrong. When fear and hatred dominates discourse, a commitment to justice and kindness and humility is precisely what the moment requires.

One more thing …

It strikes me that a number of readers may have hoped for an analysis of the draft Dobbs opinion today. Quite frankly, I talked about it so much this week, I have nothing left to say. But if you want analysis, I’ve got analysis:

Here’s my initial FAQ French Press in response to the leak.

Here’s a longer analysis of the Alito draft opinion in The Atlantic.

Here I am again in The Atlantic explaining why I don’t think Dobbs threatens gay marriage.

Here’s the emergency Advisory Opinions podcast the day after the leak.

Here’s another Advisory Opinions podcast answering common questions about the opinion.

Here’s this week’s Good Faith podcast focusing on abortion and integrity.

That’s not all. There’s a Dispatch Live, a Dispatch Podcast, an Atlantic podcast, and an Economist podcast. I’m tired just linking all that work!

One last thing …

We’re continuing our walk through Kristene DiMarco’s outstanding new album (I promise we’ll move on soon), but this song is perfect for this week. Enjoy:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.