Happy Wednesday! It sure is nice having six extra hands aboard. How did the old guard survive these past eight months?

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

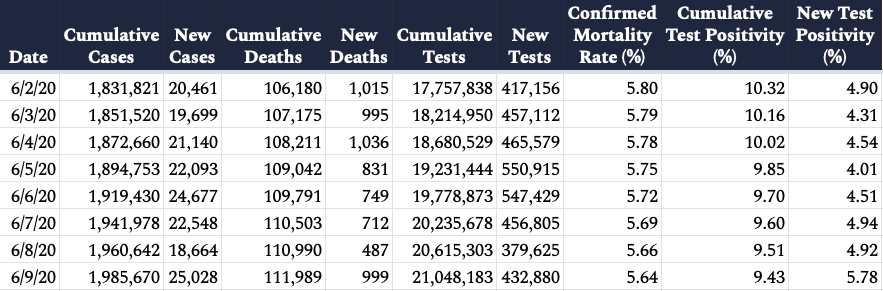

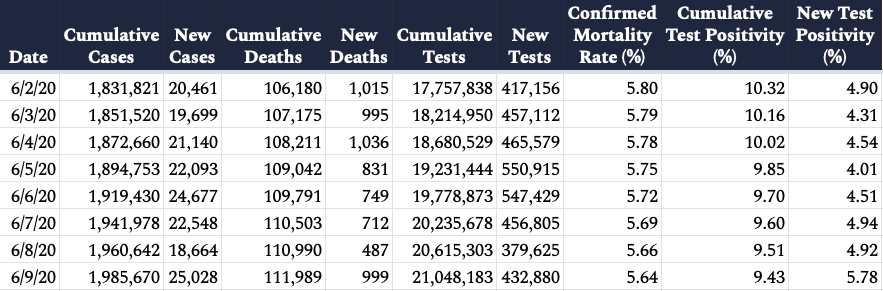

As of Tuesday night, 1,985,670 cases of COVID-19 have been reported in the United States (an increase of 25,028 from yesterday) and 111,989 deaths have been attributed to the virus (an increase of 999 from yesterday), according to the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, leading to a mortality rate among confirmed cases of 5.6 percent (the true mortality rate is likely much lower, between 0.4 percent and 1.4 percent, but it’s impossible to determine precisely due to incomplete testing regimens). Of 21,048,183 coronavirus tests conducted in the United States (432,880 conducted since yesterday), 9.4 percent have come back positive.

Despite ongoing economic damage from the coronavirus, the stock market has rebounded strongly in recent days. The S&P 500 briefly reached its January 1 peak on Monday (although it remains below its February highs), while the tech-heavy Nasdaq index finished at a record high Tuesday.

President Trump, channeling a conspiracy theory that has percolated in far-right media, accused a 75-year-old man who was assaulted by Buffalo riot police last week of being a possible “ANTIFA provocateur” who “fell harder than he was pushed.” Asked about the accusation, Sens. Lisa Murkowski and Mitt Romney denounced it while countless other GOP senators uncomfortably avoided the question.

Sen. Bernie Sanders pushed back against activists’ calls to defund the police yesterday, telling the New Yorker that he wants police officers to be better paid, better educated, and better trained to help end police brutality. “Do I think we should not have police departments in America? No, I don’t. There’s no city in the world that does not have police departments. … I think we want to redefine what police departments do, give them the support they need to make their jobs better defined.”

Sen. Tim Scott, the sole black Republican in the Senate, is putting together a GOP police reform proposal, Majority Leader Mitch McConnell announced Tuesday. The package would likely increase funding for training and strengthen police reporting requirements but would not include measures like qualified immunity reform that bills proposed by Democrats and Libertarian Rep. Justin Amash have included.

George Floyd was laid to rest in Houston yesterday after a private funeral that was attended by close friends and family members. Rev. Al Sharpton delivered the eulogy, and Joe Biden spoke during the service via video message.

What Is Antifa?

In the wake of violent rioting, President Trump last week declared his administration would “be designating ANTIFA as a terrorist group.” Questions over Trump’s legal authority to designate domestic terrorist groups aside, the tweet was indicative of an emergent line of thinking on the right that placed blame on Antifa for much of the violence cropping up in the middle of widespread anti-police brutality protests. But the tweet also raised a more foundational—and more difficult—question: What exactly is Antifa?

Antifa—shorthand for “anti-fascist”—is generally understood as a loose collection of far-left activists who are distinguished both by their outward-facing appearance and their disruptive tactics. FBI Director Christopher Wray told Congress last year the bureau views Antifa “as more of an ideology than an organization.”

People who claim the Antifa label usually dress in “black bloc”—clothed in black from head to toe with face-masks to conceal their individual identities—and are known for their willingness to deploy violence in a variety of settings. Antifa activists are most active on the margins of contemporary left-wing protest movements, and—though they’re almost always a small minority—the group’s appetite for violent confrontation has afforded them a ubiquitous notoriety, particularly in conservative circles.

It’s still unclear whether Antifa is a coherently organized movement. But although the group lacks a centralized statement of political principles, its members are united by an antipathy toward liberal notions of free speech and a deep skepticism of the normal democratic avenues for affecting political change. This persistent illiberalism is the foundation of the organization’s militancy, which stems from the conviction that violent, extralegal action is necessary to prevent the far-right from gaining a platform. In his influential 2017 Anti-Fascist Handbook, Mark Bray writes: “Anti-fascists have concluded that since the future is unwritten, and fascism often emerges out of small, marginal groups, every fascist or white-supremacist group should be treated as if they could be Mussolini’s one hundred fasci, or the fifty-four members of the German Workers’ Party that provided Hitler’s first stepping stone.”

The problem, however, is that many self-proclaimed anti-fascists have expanded the definition of “fascism” to encapsulate a wide range of political philosophies that they find distasteful. And as a result, self-identified Antifa activists have begun to violently disrupt and shut down mainstream conservative speakers like Ben Shapiro whose speech they deem to be dangerous. In recent years, Antifa groups have also physically attacked attendees at a variety of right-wing rallies and events.

Over the last few weeks, many Republicans have speculated that Antifa is largely responsible for the violence and rioting seen during some protests that swept the country after the killing of George Floyd. “With the rioting that is occurring in many of our cities around the country, the voices of peaceful and legitimate protests have been hijacked by violent radical elements,” wrote Attorney General William Barr in a statement released on May 31. “The violence instigated and carried out by Antifa and other similar groups in connection with the rioting is domestic terrorism and will be treated accordingly.”

Progressives are generally more skeptical, arguing that Antifa is a trumped-up right-wing myth, deployed either to energize the Republican base or distract from larger issues.

The nebulous character of Antifa makes it difficult to determine just how involved the group has been in the riots and looting of recent weeks. It seems likely that members who affiliate themselves with the label have had some hand in the recent unrest, but Justice Department records show no links to Antifa for any of the “51 individuals facing federal charges in connection with the unrest.”

This doesn’t necessarily mean the ties are not there—Barr told Fox News’s Bret Baier on Monday that “the initial phase of identifying people and arresting them ... [doesn’t] require us to identify a particular group”—but it’s also clear that at least a portion of the violent rioting is more cynically opportunistic than political. KSAT.com reported three Antifa members were arrested over the weekend after looting a Target in Austin, but an FBI spokesperson told The Dispatch yesterday the news story was incorrect, the individuals were not officially classified as belonging to any organized group.

“Our focus is not on membership in particular groups but on individuals who commit violence and criminal activity that constitutes a federal crime or poses a threat to national security,” the spokesperson said. “The FBI does not and will not police ideology.”

The Fall of the Confederacy (Again)

Nationwide protests over Floyd’s death have reignited the debate over Confederate monuments. Last Thursday, Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam announced his plans to remove a Robert E. Lee statue in Richmond. But by Monday, Richmond Circuit Court Judge Bradley V. Cavedo had issued a 10-day injunction blocking its removal.

In response to an 18-page lawsuit filed by William C. Gregory, Judge Cavedo’s injunction reads, “It is in the public interest to await resolution of this case on the merits prior to removal of the statue by defendants, and the public interest weighs in favor of maintaining the status quo.”

Northam claimed broad executive authority over public statues under the Virginia state code. But Gregory argued that an 1890 deed said otherwise. As the great grandson of two of the deed’s signatories, Gregory’s lawsuit argued that his family “has taken pride for 130 years in this statue resting upon land belonging to his family and transferred to the commonwealth in consideration of the commonwealth contractually guaranteeing to perpetually care for and protect the Lee Monument.”

There is movement on this issue nationally as well. In the past week, both the Marines and Navy have made plans to ban the use of Confederate symbols from their ranks, ordering the removal of “the Confederate battle flag from all installation public spaces and work areas in order to support our core values, ensure unit cohesion and security, and preserve good order and discipline.”

On Monday, Army spokesperson Col. Sunset Belinsky told Politico that “the Secretary of Defense and Secretary of the Army are open to a bipartisan discussion” on whether to rename the 10 Army installations currently named after Confederate leaders. For example, Ft. Bragg—named after Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg, “a major slave-owner” who is “largely considered to be one of the most incompetent generals of the Civil War”—had already drawn scrutiny earlier in the year after a wide-ranging piece on the issue ran in May in the New York Times.

Defenders of Confederate memorialization—such as the Sons of Confederate Veterans—claim that to destroy these monuments is to erase history. But the two biggest peaks in monument building actually occurred not during or immediately after the Civil War itself, but at the turn of the 20th century—as the anti-discrimination laws passed during the Reconstruction Era were being repealed and replaced with Jim Crow laws intended to disenfranchise and segregate blacks—and during the civil rights era of the 1960s.

According to Dr. Hilary Green—an associate professor at the University of Alabama and an expert on civil war history in the Richmond area—the intent underlying the statue’s construction should matter.

Green told The Dispatch most late-19th century Americans did not have a problem with the early Confederate commemorations because they were usually located in private cemeteries. The construction of Richmond’s Robert E. Lee monument in 1890, she argues, tells a different story. The shift of Confederate monuments to public spaces after Reconstruction was intended to “create a geography of a white versus black” with a message that African-Americans were no longer welcome.

“In what other country would there have been civil war” after which the “losing side was allowed to honor its heroes on the same soil?” asks Chris Peace, a former Republican member of the Virginia House of Delegates. Peace believes the Virginia Republican Party’s embrace of the monuments will “continue its decline electorally.”

Remember the Pandemic?

Despite the focus on racism and police brutality in recent weeks, and prevalence of mass gatherings at protest, the coronavirus has not disappeared. Far from it. According to data from the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, more than 20 states have experienced either an increase in COVID-19 cases over the past two weeks. While increased testing capacity accounts for some of this growth, it doesn’t account for all of it. Texas, Arizona, and California—all of which are moving forward with plans to reopen in one way or another—are among the states experiencing a surge.

Gov. Greg Abbott announced last week that Texas was moving to its third phase of reopening. Under these guidelines, for example, restaurants are now permitted to return to 50 percent capacity—and that number jumps to 75 percent capacity on June 12. Professional and collegiate sports teams can invite fans back to events, at 50 percent capacity. Some Texans think Abbott is moving too fast. “The data are clear,” State Rep. Chris Turner, chair of the House Democratic Caucus, tweeted. “Unfortunately, COVID-19 cases are moving in the wrong direction right now and we need to tap the brakes, not step on the gas.”

Abbott chalks any surges in positive cases up to a few high-volume facilities, pointing out that jails, nursing homes, and meat packing plants comprised over 45 percent of new cases between May 26 and June 2. Since those remarks, however, Texas has experienced record numbers of hospitalizations due to coronavirus complications. As of yesterday, the Texas Department of State Health Services was reporting 2,056 COVID-19 patients in Texas hospitals, the Lone Star State’s highest number since the outbreak began.

In Arizona, hospitals and health care workers are preparing for possible ICU and equipment shortages as the number of intensive care beds in use reaches 1,258—76 percent of the state’s capacity. To complicate matters further, about 50 percent of these patients are being hospitalized within a single health system: Banner Health. A representative from the 15 Phoenix-based hospitals informed the Arizona COVID-19 surge line that they could no longer take new patients requiring an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), an external lung machine used for patients with severely damaged lungs.

The Arizona Department of Health Services (ADHS) director sounded the alarm on Monday for hospitals across the state to activate their emergency plans. In a letter to Arizona health care workers, ADHS director Dr. Cara Christ recommended suspending or reducing elective surgeries to free up beds for coronavirus patients. While some attribute the surge in COVID-19 cases to the expiration of Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey’s stay-at-home order on May 15, Ducey has credited the state’s expanded testing apparatus. Critics of the reopening measures point out that increased testing does not explain the rise in hospitalizations.

California—despite its more gradual easing of coronavirus restrictions—is also experiencing a surge. The state reported 3,570 new positive cases last Friday, its highest daily tally yet.

Coronavirus data lag behind current events—it can take up to 14 days after infection for COVID-19 symptoms to appear, and deaths would not begin to show up in the data until weeks after that. That means these surges in states across the country took hold before the protests over George Floyd’s death. As Andrew noted in a piece last week, the virus tends to be more difficult to transmit outdoors, but “it’s undeniable [the crowds] present an elevated risk.”

Worth Your Time

The New York Times’s Elizabeth Bruenig recently spent a few weeks in her homeland of Texas, following along as the Lone Star State became one of the first states in the nation to get back to business following the coronavirus shutdown. “Something more fundamental than stir-craziness spurred Texas to reverse its coronavirus measures so swiftly,” she writes in this feature. “It was driven in part by crass political interests and in part by more ecumenical economic ones. It seemed to me that it was also motivated by something unambiguously Texan, a romantic spirit at the heart of the state that mandates fearlessness, orneriness, liberty. When disciplined, it can be fruitful, even sublime; when unmannered and libidinal, lethal.”

Have you noticed images of anti-racism protests taking place following the death of George Floyd, not just in America, but around the globe? In this piece for The Bulwark, Tamara Berens and Shay Khatiri examine how many protesters around the world have been driven by “a recognition that America has been—and ought to be—a standard-bearer for freedom and human dignity,” and that “many citizens of the free world see their own destiny as inextricably bound up with America’s.”

Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

David’s latest French Press(🔒)newsletter examines rapidly changing social attitudes on police brutality and racial justice to take an optimistic look at what a “Bill of Rights Republican Party”—as opposed to a GOP focused on “law and order”—might look like in the aftermath.

President Trump hasn’t let a pesky little thing like the Biden campaign’s explicit statements that U.S. police should not be defunded stop him from insisting Joe Biden wants to defund the police. Alec investigates in his latest Dispatch Fact Check here.

On the latest episode of The Remnant, Jonah is joined by the Washington Examiner’s Tim Carney, who has been on the ground reporting on the protests over the last few weeks. How many of the protesters are seriously out to cause trouble, and how many are there for good reasons? Also, what can be made of the “defund the police” movement, and where have our “little platoons” gone during the pandemic? Get the answers to these questions and more here, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Ted Sampsell-Jones continues his great analysis of the decisions made by Minnesota prosecutors. Today he looks at the charges against Derek Chauvin’s fellow officers and points out that progressives want to reform the very same laws that facilitate the prosecution of the cops.

Let Us Know

Antifa is, as we mentioned, short for anti-fascist, in kind of the same way that North Korea’s proper title is technically the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Sometimes a name isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

Our question to you: What are some of other examples of organizations or things with a completely misleading moniker?

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Sarah Isgur (@whignewtons), Charlotte Lawson (@charlotteUVA), Audrey Fahlberg (@FahlOutBerg), Nate Hochman (@njhochman), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Photograph by Stephanie Keith/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.