Bernie Sanders has nowhere to go, so there he was on the debate stage Sunday night across from the Democratic frontrunner, Joe Biden. Despite having lost big at the ballot box in recent primaries, Sanders says he is staying in the race to influence the direction of his party. He wants more Democrats to adopt his peculiar views. However, it’s not just Republicans or conservatives who find Sanders’ opinions curious, or even offensive. Sanders has earned the criticism of his fellow Democrats for repeatedly praising Cuba’s supposedly excellent literacy programs.

Several of the questions at the debate Sunday night were intended to explore Sanders’ thinking. And his answers illustrate just how confused he really is. For instance, debate moderator Ilia Calderón asked Sanders about his praise for certain aspects of the Castro regime. “Cuba has been a dictatorship for decades,” Calderón noted. “Shouldn't we judge dictators by the violation of human rights and not by any of their alleged achievements?”

In his answer, Sanders quickly pivoted to a defense of China’s economic policies. Here was his answer in full (emphasis added):

Well, I think you can make the same point about China. China is undoubtedly an authoritarian society. Okay? But would anybody deny, any economists deny that extreme poverty in China today is much less than what it was 40 or 50 years ago? That's a fact. So I think we condemn authoritarianism, whether it's in China, Russia, Cuba, any place else. But to simply say that nothing ever done by any of those administrations had a positive impact on their people, would I think be incorrect.

That is a fact. Except, the Chinese experience directly contradicts the point Sanders was trying to make.

China’s economic growth over the last 40 years is due to the government’s adoption of liberal economic reforms—the same types of policies that Sanders often rails against. China’s relative economic prosperity isn’t the result of the politburo’s planning. Instead, the Chinese government realized it had to allow more domestic competition and economic freedom in order for its people to be raised out of poverty.

A report published by the Congressional Research Service (CRS) in June 2019 contains a succinct summary of this transformation in China’s thinking:

Prior to the initiation of economic reforms and trade liberalization nearly 40 years ago, China maintained policies that kept the economy very poor, stagnant, centrally controlled, vastly inefficient, and relatively isolated from the global economy. Since opening up to foreign trade and investment and implementing free-market reforms in 1979, China has been among the world’s fastest-growing economies, with real annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaging 9.5% through 2018, a pace described by the World Bank as “the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history.”

Now, we should take China’s self-reported economic statistics with a large grain of salt. Much of the Chinese economy is a black box and is difficult to independently measure. The government has an incentive to exaggerate the economy’s performance and there are warning signs that all is not as well as Xi Jinping’s regime wants it to seem.

Still, there is no question that liberalization within China led to its economic boom—and not top-down authoritarian, or socialist policies.

As the CRS report lays out in clear detail, the Chinese government finally saw the error of its totalitarian ways beginning in the late 1970s, at least with respect to the economy. The government allowed farmers to sell some of their crops in free markets, eliminated many price controls, “decentralize[d] economic policymaking in several sectors,” and liberalized trade, among other reforms. The cumulative effect of these and other policies led to “substantially faster” growth than in the pre-reform period, when the Chinese people lived in abject poverty and suffered during periods of mass starvation.

That is, the Chinese government got mostly—but not entirely—out of the way of its own citizenry. This is the opposite of what Sanders envisions.

Of course, Sanders wants the U.S. government to have more control over the domestic economy and certain segments of society. In his simplistic worldview, centralized decision-making will benefit the majority of the people. So, when he looks at China, Russia, and Cuba he sees politico-economic regimes that have the type of concentrated political power he wants the U.S. to adopt, surmising that more socialism will lead to more widespread prosperity. The truth is close to the opposite. Just look at China’s recent history.

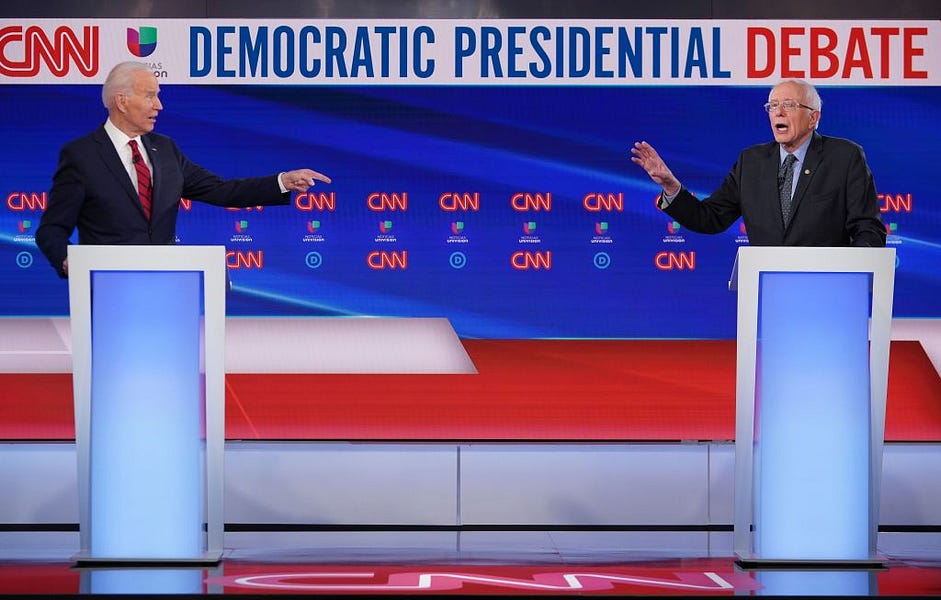

Photograph of the March 15 Democratic primary debate by Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.