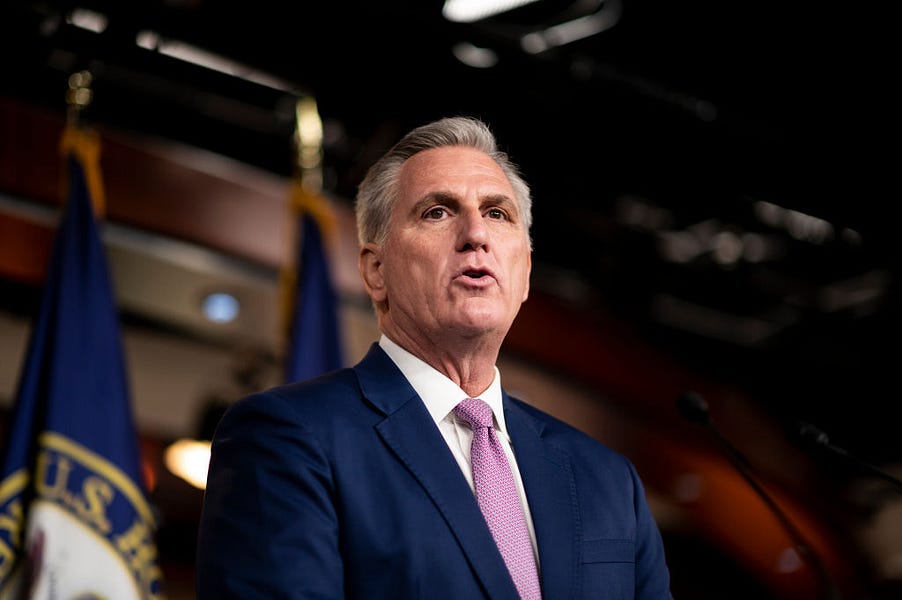

When was Kevin McCarthy more likely to be deceiving his audience? When he told congressional Republican leaders days after the January 6 attacks that he would tell then-President Donald Trump that “it would be my recommendation you should resign,” or last week when McCarthy told reporters he “never thought that [Trump] should resign.”

Anyone who has followed McCarthy’s balky, grasping, two-decade-long climb from representing Bakersfield in California’s state assembly until now, standing for a second time at the threshold of becoming speaker of the House of Representatives, will know that the answer is easy: “both times.”

McCarthy’s chief political gifts are a self-abnegating elasticity that allows him to wrap himself around whoever’s fingers seem the most useful at a given moment and a relentless ambition that has allowed him to endure the many humiliations on his path to power. He was paying lip service to Rep. Liz Cheney and others who wanted Trump out of office then, and he is paying lip service now to Rep. Matt Gaetz and others who squawk in exultations at the thought of Trump returning to power and punishing their enemies.

The narrative favored by Democrats and many in the press is that McCarthy was going to pressure Trump to step aside but then chickened out can’t really be accurate because McCarthy was never going to push Trump—or anyone—into anything. Trump would have laughed in his face. But the idea that McCarthy was once going to put the interests of Congress ahead of his own ambition and then changed his mind supports the central premise for much of the political coverage today: Trump as the center of the universe.

Trump’s civil war against those in the GOP who have not accepted his alternate history of the events from November 2020 to February 2021 is real, and it may end up being the single most important thing in American politics today. If Trump breaks the GOP’s back with a bunch of primary wins for his candidates, starting next week in Ohio with J.D. Vance and continuing through May in Nebraska, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and, the big one—Georgia’s gubernatorial race—it will have lasting, painful consequences. If the Trump faction dominates the primaries and Republicans go on to have a big midterm success anyway, the party may be entering a long captivity by the culture warriors on the populist right. The next six years for the Republican Party may be all about gay sex-ed, testicle tanning, and tirades about Twitter algorithms. Change the elephant to a hog-tied Mickey Mouse, presto change-o.

But that’s just one possible outcome. Trump may watch his picks go down one after another and Republicans win big in November with candidates focused on the economy, or, Trump may win a bunch of ugly primaries and then cost Republicans the Senate again. But none of that is really what complicates McCarthy’s run for speaker.

Trump is probably as happy to have a supplicant, chastened McCarthy as speaker as anyone—and probably more than any of the hardcore nationalists in the Freedom Caucus. McCarthy’s flexibility is useful, and he is experienced. You put one of the true believers in there and they may cause trouble. As one top Trumpist told NBC News about the former president’s feelings toward McCarthy: “He accepts Kevin for who he is. It’s not like he really trusts him.”

McCarthy’s previous bid to be speaker, in 2015, ended in tatters. There are a lot of reasons he failed, but the main one was that members of the Freedom Caucus believed McCarthy would enforce party discipline to do as then-Speaker John Boehner had done and force votes to end government shutdowns, limit wild-eyed oversight demands, etc. McCarthy since then has made some bones with the populists in his time as minority leader, notably with the ritual sacrifice of Cheney. The muted response from the Freedom Caucus about McCarthy’s embarrassment last week speaks to that.

Indeed, McCarthy's latest January 6 stumbles—first denying he ever said such a thing and accusing the “corporate media” of making the story up and then having the audio served up to him like creamed chipped beef on toast—gives the radical nationalists even more power over McCarthy. The speaker-in-waiting has had to move away from the more modest public statements he made in public in January 2021 about Trump’s responsibility for the mob he sent to besiege Congress. Every time McCarthy has to go begging Trump’s pardon and resoothe the Freedom Caucus, his leash gets a little shorter.

One wonders, for example, whether McCarthy would be so saucy now in dismissing the growing calls from radical Republicans for the impeachment of President Biden as he was on March 14 when he intoned to Fox Business, “We believe in the rule of law.” To the dozen-plus House Republicans who have already signed on to impeachment resolutions, that didn’t sound very nice. Betcha the next time he’s asked about it, McCarthy will be more sympathetic. That, in turn, would be a boon to Democrats who would love to talk about that and make McCarthy, who is probably less popular, if less known, than Nancy Pelosi, a bigger part of the midterm campaign.

McCarthy is badly in hock to Trump and the Freedom Caucus, but their demands will only increase from here. While that’s certainly not enough to cost Republicans the House by itself, it could shrink the new majority. McCarthy’s obvious hope is that the coming wave will flood the House with new, more reasonable members from swing districts—new members who he recruited and raised money for—and they will help lift him beyond the reach of the Freedom Caucus. But if the wave comes up short of expectations, say only 15 to 20 seats, McCarthy will be a handmaiden to the same bunch that denied him the speakership seven years ago.

Trump is in this story, but it is not a story primarily about Trump. This is about what becomes of the deeply divided House Republicans and their expected windfall. That’s a story that predates Trump and will be around after he is gone.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.