A new poll out of Virginia is warming the hearts of that plucky clutch of Republicans who still dare to dream two things without much evidence: 1) That their party is particularly interested in an alternative to nominating former President Donald Trump a third time, and 2) That small-government, traditional conservatism, and good character still have places of prominence in the GOP.

The survey from Virginia Commonwealth University shows Gov. Glenn Youngkin trouncing President Joe Biden in a hypothetical presidential matchup for Virginia’s 13 electoral votes. Youngkin’s 7-point lead compares favorably to Trump, who trails Biden by 3 points, and to Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who was tied with Biden.

Youngkin has put off talk about a possible presidential run until after this year’s November 7 statewide elections that will serve as a referendum on his leadership after two years in office. And like with Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp, the appeal of a late entry by a popular, conservative governor continues to tantalize members of a party still hoping for more choices.

The poll lands as the traditional wing of the GOP is coming to grips with the depth of its predicament. It’s not just that Trump is crushing the competition nationally and in key states, or the ways in which the former president’s ever-deepening legal woes simultaneously hurt his chances in a general election and help his standing with primary voters.

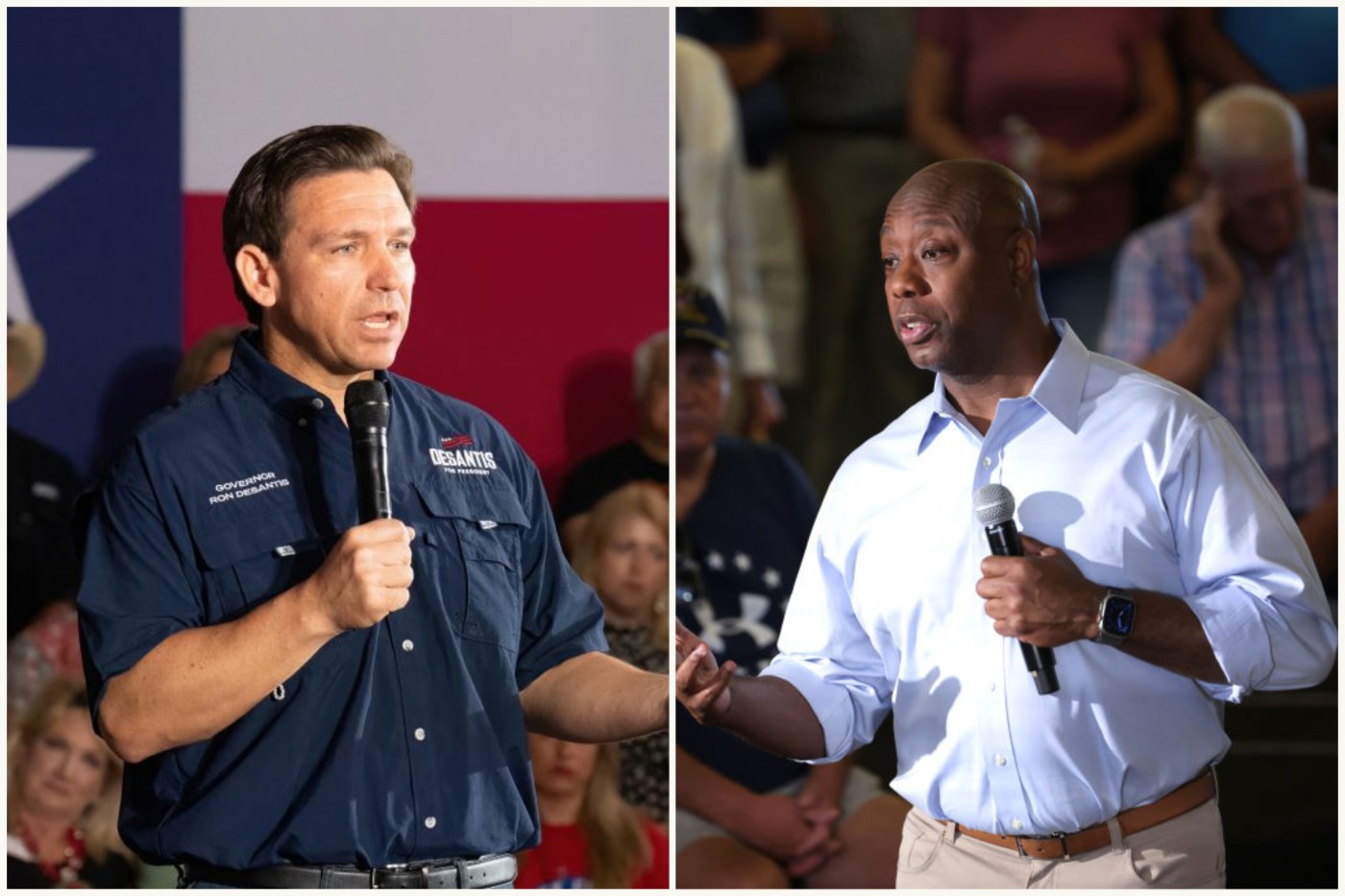

It’s also not just that the anointed Trump slayers, particularly DeSantis, have struggled to get traction. It’s that they’re not espousing the views that would soothe the jangled nerves of those Republicans who imagine a return to the way things were before Trump became the master of the GOP universe.

The Wall Street Journal editorial board ripped DeSantis last week for economic proposals that seek to combine traditional Reaganite policies with the kind of grievance-based economic pandering that the paper said was “the kind of fusionism that would have taxed Robert Oppenheimer.”

The editorial went on to add that DeSantis “needs a vision for American renewal that transcends Mr. Biden’s plans to use big government for income redistribution and Mr. Trump’s desire to use it for political ‘retribution.’”

Once the clear favorite of the Murdoch media empire that owns the Journal, DeSantis now finds himself blamed for both being bad at politics and policy. And as is almost always the case when policy people and ideologues think about politics, they imagine that a lack of doctrinal purity is a problem rather than an advantage.

Then there’s South Carolina Sen. Tim Scott, who has shown significant momentum as DeSantis has stalled. But the traditionalists are unhappy with Scott for echoing some Trump talking points about the “weaponization of the Department of Justice,” and for declining to hold Trump accountable for the January 6 riots.

The problem is the same for Scott as it is for DeSantis. The small but influential group of conservatives who are his natural constituency does not want him to give the rest of the electorate too much of what it wants. As Scott tries to thread his way through the Trump minefield, he does so with the pressure to satisfy core supporters while still broadening his reach.

This is, of course, the very nature of politics: trying to get what you want without losing what you have.

The work is made more complicated when what you have is access to big donors and tastemakers who are always prone to overstate their influence, but never more so than in the era of Trumpian populist outrage. Just look at what all that money and press did for DeSantis. Not only does the candidate have to carry the high expectations set by someone else, but also the demands made by and negative public perceptions of his or her benefactors. The hands that feed you also expect to lead you.

Today’s Republican Party is torn between the pro-Trump and anti-Trump factions. As the very useful New York Times/Siena College poll shows, the breakdown goes something like this: 37 percent MAGA, 25 percent anti-MAGA, and 37 percent in between.

That means to get past Trump, another candidate would need to count on the solid support of most of the anti-MAGA faction and then run like hell to try to convince more than two-thirds of the persuadable 37 percent that he or she is the right person for the job.

DeSantis tried working from the other direction, targeting Trump’s base before appealing to the persuadables and the anti-MAGA stalwarts. He ended up failing to crack Trump’s core and alienating the rest of the party. Now, to try to get back on track, the pressure is on to halt Scott’s momentum. Like crabs in a bucket, DeSantis and Scott’s other rivals may succeed in pulling him back down just as he is about to make his escape.

But the hardest candidates for Scott or DeSantis to deal with aren’t candidates at all, particularly Youngkin.

It was easy to see the appeal of the Virginia governor even before the new poll that shows him trouncing Biden: A popular blue-state Republican who could shore up GOP losses in the suburbs and bring states like Georgia and Arizona back into the fold while still making a play in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Michigan. An establishmentarian who managed to slip past MAGA candidates in his own primary without alienating them or standing too close to Trump. A policy conservative with moderate style and a personal fortune sufficient to skip the scut work of raising seed money.

Nor is it impossible to imagine a scenario in which Youngkin could ride in on a white horse late this year, skipping the punishing early debates and arriving just in time to carry his new momentum into the first contests. It certainly could happen.

It is easier to imagine the alternative, though: As chatter about Youngkin’s potential candidacy ramps up in the fall, donors, other Republican governors, activists, and operatives pull back from the Trump alternatives already running. Those alternatives meanwhile are busy ripping each other to shreds trying to unite the small anti-Trump portion of the party.

But when the white knight arrives, his horse throws a shoe. Too many early state voters have already made their commitments and Youngkin can’t find a way to get to a win before Super Tuesday. Then he’s just one more candidate facing pressure to drop out at the end of February.

The idea of a Youngkin candidacy depends on two unknowns: his appeal as an actual candidate outside of Virginia and the viability of DeSantis and Scott by the time we get to Thanksgiving. If his fellow Republican governor has already crashed and burned, the opening for Youngkin would be clear. The same is true if Scott can’t make it stick as the optimistic conservative cheerleader in the race. But if either or both of them have a solid footing, Youngkin would be more likely to help Trump rather than hurt him.

The risk for conservatives is that they won’t be able to come to terms with the flawed choices they have when compared to the still-pristine idea of another candidate with whom they will also invariably become disenchanted. But the rewards for Republicans if Youngkin really could make a late charge would be enormous.

He and his party have three months to sort out which of those scenarios looks most likely.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.