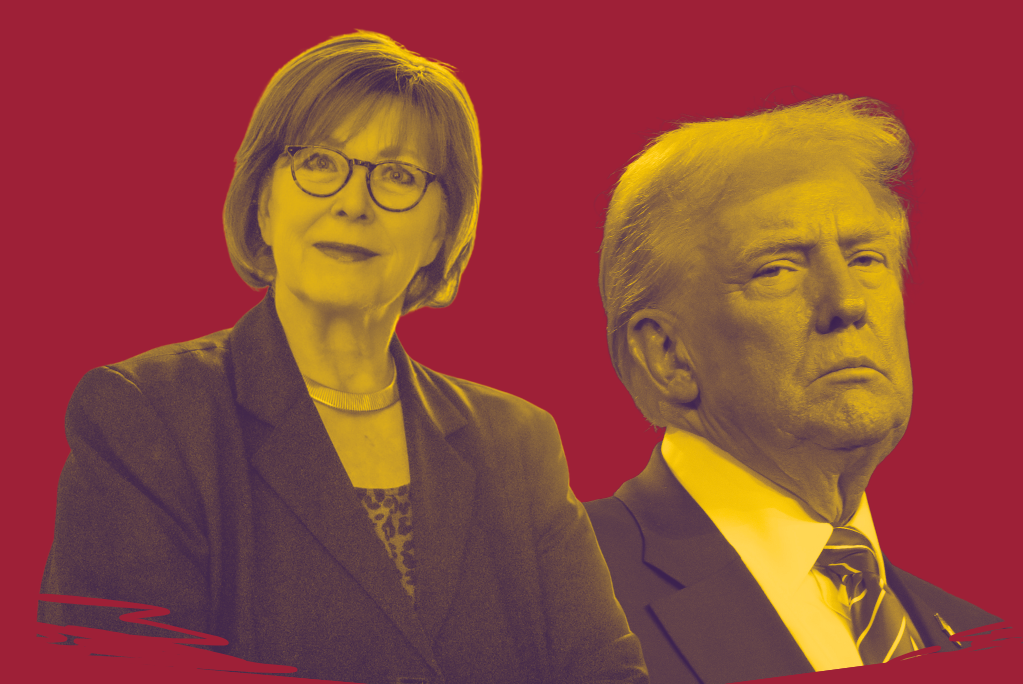

J. Ann Selzer planned to step back from election polling at the end of 2024. She had spent three decades working with the Des Moines Register and other media outlets, earning a reputation as “the best pollster in politics” for her consistent and reliable work. Selzer’s polls had correctly predicted the winner of every presidential race in Iowa since 2008, and she was hoping to end her election-related work with one last accurate survey of public opinion.

But things turned out differently.

Selzer’s final poll of the 2024 Iowa electorate, commissioned by the Des Moines Register, found that Vice President Kamala Harris was leading Donald Trump by 3 points. She was wrong. In fact, Trump won the state by more than 13. To her credit, Selzer was quick to own up to the margin between her poll and the eventual outcome. She explained her methodology and released the data she had collected in the process.

“Polling is a science of estimation, and science has a way of periodically humbling the scientist,” she said in a November 17 farewell column for the Register. “So, I’m humbled, yet always willing to learn from unexpected findings.”

President Donald Trump, however, doesn’t seem to think “humbled” is enough. That same day, Trump took to Truth Social to accuse Selzer of intentionally fabricating her poll and committing possible election fraud. A month later, he sued Selzer and the Register for alleged election interference and violations of the Iowa Consumer Fraud Act.

It’s difficult to imagine a more thorough and obvious violation of basic First Amendment principles than this lawsuit. Polling the electorate is election participation, not interference—and reporting your findings is protected speech whether your findings turn out to be right or wrong. Iowa’s laws on election “interference” are about conduct such as using a counterfeit ballot or changing someone else’s ballot. This does not and cannot include asking voters questions about their votes.

Trump’s claims of consumer fraud have even less merit. Consumer fraud laws target sellers who make false statements or engage in deception to get you to buy something, like a sleazy car salesman rolling back the odometer on an old sedan. This cannot logically—or legally—apply to a newspaper pollster who makes a wrong prediction.

Consumer fraud statutes have no place in American politics or in regulating the news. But it has become an increasingly popular tactic to use such laws in misguided efforts to police political speech. For example, a progressive nonprofit tried to use a Washington state consumer protection law in an unsuccessful lawsuit against Fox News over its COVID-19 commentary. And attorneys general on the right used the same, “We’re just punishing falsehoods” theory to target progressive outlets. Both Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey and Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton opened investigations into the nonprofit Media Matters for America for allegedly manipulating X’s algorithm with “inauthentic behavior.” In the Texas suit, Paxton argues that he can use the state’s Deceptive Trade Practices Act to punish speech even if it is “literally true,” so long as officials think it’s misleading.

“If you have the threat of legal action hanging over you for what you’re about to say, you will think twice before saying it—and that’s the point.”

Efforts to prohibit purportedly false statements in politics are as old as the republic. Indeed, our First Amendment tradition originated from colonial officials’ early attempts to use libel laws against the press.

America rejected this censorship after officials used the Sedition Act of 1798 to jail newspaper editors for publishing “false” and “malicious” criticisms of President John Adams. After Thomas Jefferson defeated Adams in the election of 1800, he pardoned and remitted the fines of those convicted, writing that he considered the act “to be a nullity, as absolute and as palpable as if Congress had ordered us to fall down and worship a golden image.”

Trump’s allegations against Selzer are so baseless that you’d be forgiven for wondering why he even bothered. That is, until you realize that these claims are filed not because they have any merit or stand any chance of success, but in order to impose punishing litigation costs on his perceived opponents. The lawsuit is the punishment.

In fact, Trump has a habit of doing this. He once sued an architecture columnist for calling a proposed Trump building “one of the silliest things anyone could inflict on New York or any other city.” The suit was dismissed. He also sued author Timothy L. O’Brien, business reporter at the New York Times and author of TrumpNation: The Art of Being The Donald, for writing that Trump’s net worth was much lower than he had publicly claimed. The suit was also dismissed.

But winning those lawsuits wasn’t the point, and Trump himself said so. “I spent a couple of bucks on legal fees, and they spent a whole lot more,” he said. “I did it to make his life miserable, which I'm happy about.” Back in 2015, he even threatened to sue John Kasich, then-governor of Ohio and a fellow Republican candidate for president, “just for fun” because of his attack ads.

This tactic is called a “strategic lawsuit against public participation,” or SLAPP for short, and it’s a tried-and-true way for wealthy and powerful people to punish their perceived enemies for their protected speech. It’s also a serious threat to open discourse and a violation of our First Amendment freedoms.

Lawsuits are costly, time-consuming, and often disastrous to people’s personal lives and reputations. If you have the threat of legal action hanging over you for what you’re about to say, you will think twice before saying it—and that’s the point. Trump’s dubious legal theory is a blatant abuse of the legal process, one that we cannot let stand. If we sued people every time we thought someone else was wrong about politics, nobody would speak about politics. A lawsuit requires a credible basis to believe your rights have been violated. You have to bring facts to court, not baseless allegations.

That is why my organization, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), is defending Selzer pro bono against Trump’s SLAPP suit. By providing legal support free of charge, we’re helping to remove the financial incentive of SLAPP suits—just as we did when a wealthy Idaho landowner sued over criticism of his planned airstrip, when a Reddit moderator was sued for criticizing a self-proclaimed scientist, and when a Pennsylvania lawmaker sued a graduate student for “racketeering.”

The protection of unfettered freedom of expression is critical to our political process. Any attempt to punish and chill reporting of unfavorable news or opinion is an affront to the First Amendment. Our rights as Americans, and participants in our democracy, depend on it.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.