Behold what remains of the red tsunami, lapping gently at our ankles.

Oh dear.

Of the three House scenarios the party contemplated before Election Day, that might be the worst.

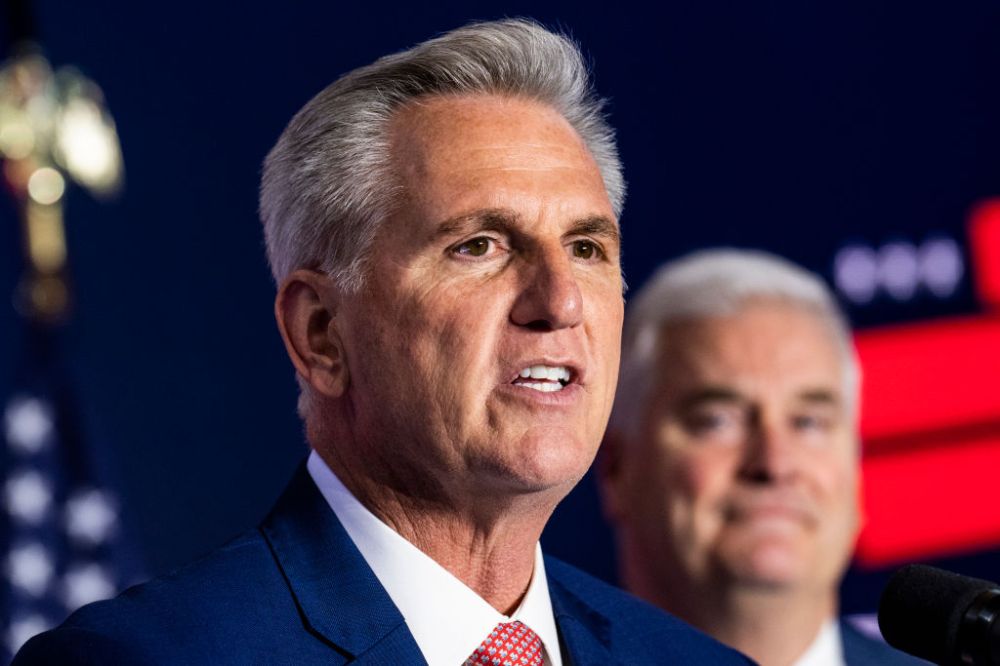

The best was a huge Republican victory that would hand Kevin McCarthy a 40-seat majority. With that much cushion to work with, he might—might—have managed to sideline the MAGA mini-caucus. When the time came for a new round of Ukraine funding, say, he could have put a bill on the floor knowing that it would pass with 218 Republican votes even if the 20 or so most loudmouthed authoritarians in his ranks objected.

Next best, arguably, was Republicans landing in the House minority again. No one wants to lose, but if the shining lesson from last week’s results is that swing voters despise Trumpy politicians, the GOP might have profited from having the MAGA faction out of the spotlight for the next two years. Marjorie Taylor Greene is a comparatively minor liability to the party as a backbencher in a Republican caucus with no actual power. She’s a major liability when she’s the potential deciding vote on whether to raise the debt ceiling.

That brings us to the third scenario, the one we’ve got, in which the GOP wins the House narrowly and spends its two years in power mired in a destructive civil war over which faction should control the agenda. McCarthy probably ends up being ousted as speaker sooner rather than later as efforts to corral the caucus prove hopeless. Dysfunction reigns. Dismayed swing voters take in the spectacle and conclude in 2024 that Republicans aren’t fit to govern.

You might object to the order of my ranking on grounds that no partisan would ever prefer to have fewer seats in the House than more seats. To which I say: You sure about that?

Rep. Thomas Massie, R-Ky., told Semafor on Wednesday that he believes that the party's right wing will gain immense influence if House Republican leaders like Kevin McCarthy have few votes to spare. He cast himself as playing a role similar to that of Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., a Democrat [who] played an outsized role in his party’s agenda in the 50-50 Senate.

…

“You’re talking to the wrong guy if you’re trying to find somebody who's heartbroken that we don't have a 40 seat majority,” Massie said on Wednesday. “I want this outcome where it's a slim majority.”

Massie is among the more radical members of the MAGA faction. Given a choice between a large majority for his party in which his vote doesn’t matter much and a tiny one in which it matters a lot, he prefers the outcome that maximizes his and the radicals’ power.

So does this imbecile, who’s grousing about a “stolen election” on Twitter today and whose outsize leverage in the new majority will make her a national face of the party for the next two years.

If you believe the best thing that could happen to the GOP long term is ridding itself of its Trump baggage, the fact that the House went Republican this year under his leadership has to be a matter of mixed emotions. The party underperformed expectations badly, yes, and the crop of conspiratorial MAGA cranks on the ballot went down in flames from coast to coast.

But some Trump diehards will look at the results, disappointing though they may be, and draw the lesson that they can still win control of Congress by nominating populists. Some will even tell you, à la Thomas Massie, that a smaller, more radical majority is preferable to a larger, less radical one.

For the average Republican partisan, though, it’s worth asking whether control of the House with a three-seat majority is more trouble than it’s worth.

The shining virtue of having a majority, of course, is that it gives Republicans a veto over the Democratic agenda. Gone are the days of Joe Manchin and his party shoehorning massive spending bills into reconciliation and sending them to Biden’s desk with bare majorities. However much damage you fear the left might have done the country with another two years of total control, you should feel a commensurate amount of relief today.

Two cheers for divided government.

But only two. After all, the single least defensible policy implemented in Biden’s first two years as president wasn’t enacted by Congress but ordered by presidential diktat. Year by year, the executive’s powers expand at the expense of our paralyzed, enfeebled legislature. The end of congressional control by Democrats unfortunately doesn’t mean the end of major Democratic policy mischief.

Relatedly, the House remaining in Democratic hands wouldn’t necessarily have meant drastically worse Democratic policy mischief. The magic number for Biden’s party in the Senate was 52 seats, enough that they could ignore Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema and finally jettison the filibuster. That would have unlocked radical legislative possibilities—codifying Roe v. Wade, federal election reform, maybe even making Washington D.C. a state.

They didn’t get there. At best, they’ll have 51 seats. The Manchinema “veto” over the left’s worst excesses will survive for two more years irrespective of who controls the House. And since Manchin is up for reelection in 2024 in a Trump +40 state, he has every electoral incentive to vote like a conservative for the next two years.

A House majority means Republicans will control committees and therefore wield the power to investigate the White House, a valuable asset—potentially. If they focus on matters of broad public concern, like the withdrawal fiasco in Afghanistan or the border crisis, they might do Biden real damage. Instead they’re likely to prioritize the right’s hobby horses, from Hunter Biden’s business dealings to the FBI search of Mar-a-Lago, which are more likely to turn into Benghazi 2.0. If the outcomes of those probes end up not meeting the extravagantly high expectations of Republican voters, an all but impossible task, disappointed base voters will rage against their own leadership.

And because the MAGA wing will insist on a reprisal for Trump’s two impeachments no matter what, McCarthy may be forced to pursue an ill-advised impeachment even if the findings of an investigation don’t justify one.

It’s conceivable that losing the House this year would have been better for Republicans in the medium term. With Democrats back in control of both chambers, public fatigue at liberal governance would have grown for another two years. Aggressive progressive legislation (assuming it could gain the Manchin/Sinema seal of approval) would have alienated more swing voters. That would have set up Republicans nicely to win control of everything in 2024, albeit at the steep cost of two more years of Democrats enacting their agenda.

Instead, Kevin McCarthy and his unmanageable caucus are about to show the country how fractious and sporadically reckless government by Republicans is. There could be a debt-ceiling crisis, an unnecessary shutdown, a nasty standoff over Ukraine, an unwarranted impeachment, and more. Barack Obama was saddled with a radicalized Republican House in 2010 and was reelected easily two years later, picking up seats in both the House and the Senate. Would he have fared as well if Democrats had held onto Congress for the final two years of his first term?

The point here is not that winning the House is worth nothing to Republicans. Of course it is. The question is whether the benefits of a three-seat majority exceed the costs.

And there are costs.

In a saner universe, winning the House would be an unvarnished good and a tantalizing opportunity. It’s a chance for the GOP to pass popular bills and to preview for voters what they can expect if they put Republicans in charge of the federal government in 2024.

It’s also an opportunity to steer the party away from Trump, the sort of thing new congressional leadership should logically want to do following an election in which his faction was broadly repudiated. Prioritize a working-class legislative agenda but minimize partisan warfare for its own sake. Ignore Trump when he inevitably begins making insane demands driven purely by spite, like refusing to raise the debt ceiling or impeaching Joe Biden multiple times. Clam up about “stolen elections.” Do what you can to establish the House as a counterweight to Trump on the right.

None of this will be happening in our universe.

In our universe, with Kevin McCarthy’s ability to govern in the hands of Massie, Greene, and Matt Gaetz, the razor-thin Republican majority will become a vehicle for populist performance artists to prove to the base their willingness to fight, mainly by fighting their own leadership. A debt-ceiling crisis is so likely that the outgoing Congress might try to raise it during this year’s lame-duck session. Republicans will battle each other over Ukraine aid even though that aid reliably enjoys strong majority support in polling. The caucus will split over whether to advance federal abortion restrictions or to defer to the states. Pressure will mount on leadership to pursue the doomed impeachments of various Biden officials. And if and when Trump is indicted, no matter how justified the charges might be based on the evidence, McCarthy will face strident demands to retaliate legislatively against the DOJ.

If you’re a swing voter and you liked “defund the police,” you’ll love “defund the Justice Department.”

The bottom line is that if the 2022 midterms were fundamentally about rejecting MAGA weirdos, a hard dose of government by MAGA isn’t the obvious response. But that’s what the country is going to get.

Well, either that or a Republican caucus that’s paralyzed by its own divisions.

Reports are swirling that hardline populist Andy Biggs is planning to challenge McCarthy in Tuesday’s secret ballot to nominate someone for speaker. McCarthy will win handily, of course, but so long as Biggs gets a handful of votes, it’ll mean that McCarthy won’t have 218 in the bank when the full House votes on the record to elect a speaker in January.

He’ll have to make concessions to the MAGA faction to win their support for that one and those concessions won’t be pretty. Their top demand is a rule change allowing any House member to offer a motion to vacate the chair, i.e., to initiate a no-confidence vote in the speaker. That motion is what drove John Boehner to resign in 2015; since then, only the leadership of each House caucus has been empowered to offer a motion to vacate. If McCarthy caves and reinstates the old rule, it means the MAGA wing could try to depose him at any time.

And if McCarthy is deposed at some point, he’s apt to be replaced by Jim Jordan or Jim Banks or some other hardline populist who’s destined to govern in a way that alienates more swing voters than it attracts.

The situation is so fluid that there’s reportedly chatter among House Democrats about nominating Liz Cheney as their choice for speaker against McCarthy. That seems too cute by half but it’s clever in theory. If all 216 Democrats backed her, they’d need just two anti-Trump Republicans who plan on retiring after the next term to come aboard in order to hand her the gavel. (Cheney will be out of Congress come January but the House is free to choose anyone as speaker under the Constitution, not just an incumbent member.)

If you’re a House Republican who’s keen to signal a new direction for the party away from Trump, you should be considering your options. And there are some Republicans like that.

Speaker Cheney is a 1,000-to-1 shot. But pretty much every outcome in the House next year feels like a 1,000-to-1 shot right now.

And then there’s Trump. There’s always Trump.

The flaw in my theory that McCarthy would have had an easy time governing with a 40-seat majority is that Trump is a tremendous force multiplier for populists. McCarthy doesn’t care whether Greene or Gaetz is mad at him. But he does care, for obvious reasons, whether Trump is. Trump commands the base, for now. McCarthy loses the support of his party if he loses the support of Trump.

Moderates in the caucus understand that too. MAGA candidates may have had a bad year electorally but not as bad as the Republicans who voted to impeach Trump last year. Of those 10, only one—Dan Newhouse—has won reelection to Congress as I write this on Monday. Another, David Valadao, is leading in his House race in California. The other eight are goners.

If you’re a “normie” Republican in the House and the Dear Leader announces on Truth Social that the time has come to impeach Biden or defund Ukraine or block the debt ceiling or what have you, you’re inviting a credible primary challenge if you don’t go along. In which case, even a 40-seat cushion wouldn’t necessarily have been comfortable for McCarthy. So long as Trump is barking orders and acting as political muscle for his sycophants in the MAGA faction, they’ll punch way above their weight.

Which means winning the House would have been generally chaotic and unhappy for Republicans no matter the margin.

In fact, with Trump already palpably nervous about a challenge from DeSantis, the moment is coming when he demands that every member of the House Republican caucus declare whether they’re endorsing him in 2024, beginning with leadership.

One of his most contemptible stooges, Elise Stefanik, got out of the gate quickly by pledging her devotion. Backbenchers will be expected to follow, knowing that if they insist on keeping their powder dry for DeSantis, Trump will consider it an act of extreme disloyalty and seek to punish them for it later.

That’s what you sign up for nowadays if you’re foolish enough to seek power in a party ruled by a deranged monarch. Every litmus test you pass is soon forgotten, replaced in short order by a new test on which your standing in the party depends entirely. As some are learning the hard way, you need only fail once to end up on the official enemies’ list.

For McCarthy and the moderates, the next two years will be an endless series of unreasonable litmus tests made of them by the MAGA faction. They’ll pass those litmus tests when the stakes are low. But when they’re high, as they’ll be in a debt-ceiling standoff, they’ll face an impossible choice between doing what populists want and committing political suicide among swing voters in the process or defying the populists and being despised utterly as weak suckers who refuse to “fight.” No matter what they do, some key chunk of the electorate ends up furious at them.

Even the hoped-for ascent of Ron DeSantis probably won’t save them. In theory, having DeSantis explode in 2024 polls following his landslide victory in Florida will ease some of the pressure on moderate Republicans to do Trump’s bidding. But in practice, DeSantis will be keen not to let Trump get to his right ahead of the primaries, knowing that to do so would call his own credentials as a “fighter” into question. I don’t foresee DeSantis demanding that Republicans block a debt-ceiling hike, knowing how reckless that would be, but I don’t foresee him giving McCarthy cover to raise it either by speaking up in favor of doing so.

House Republicans are on their own for the next two years, trapped in a white-hot spotlight as the governing majority with some of the craziest figures in the party, with no prospect of enacting any legislation and no near-term prospect of ridding themselves of Trump. To the normies in the caucus, a three-seat majority must feel like the end of an especially creepy wake-up-in-hell episode of The Twilight Zone. It couldn’t have happened to a more deserving bunch of cowards.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.