“We ran the best campaign we could, considering Joe Biden was president,” an aide for the losing candidate told Politico after Tuesday’s returns were in. “Joe Biden is the singular reason Kamala Harris and Democrats lost tonight.”

“He shouldn’t have run,” former Harry Reid aide Jim Manley complained of the president. “This is no time to pull punches or be concerned about anyone’s feelings. He and his staff have done an enormous amount of damage to this country.”

“Malpractice” is how one Democratic official bluntly described Team Biden’s hubris about reelection to Reuters. “No one would tell him ‘no.’ So it’s Joe, but also Joe’s core apparatus. Stunning and well-documented chickens coming home to roost.”

In an interview with the New York Times, historian Douglas Brinkley noted that Biden “was supposed to be the bridge, a transition bridge for the next generation of Democrats,” recalling the president’s famous comment during the 2020 campaign about how he would approach his time in office. When he foolishly chose to run for a second term, Brinkley added, he “blew up the bridge.”

You’ll find comments to that effect in nearly every election postmortem in America today, laying blame for Democrats’ defeat in Biden’s lap. Cards on the table: I dislike this argument instinctively.

That’s not because I have affection for the president or because I’m keen for responsibility to fall on Harris. It’s because, given the magnitude of what’s happened, it’s important to be clear-eyed about moral culpability. Americans knew what they were voting for this time and voted for it anyway. Wittingly or not, any attempt to shift blame elsewhere amounts to excusing them for what they’ve done.

Still, as an analytical matter, the question is worth considering: Might things have been different had a senescent Joe Biden chosen not to run for reelection when poll after poll showed Americans aghast at the thought of a man in his condition serving for four more years?

The strange answer, I think, is obviously—and also obviously not.

What might have been.

Airdropping a mediocre politician like Kamala Harris into the thick of a presidential campaign three months before Election Day was not the optimal strategy for victory, we can all agree.

“We should have had a primary with all the talent and it would have given us a better chance to educate everyone on who the candidates were,” one Democratic donor told the Times. Biden could have announced after the 2022 midterms that he’d retire after one term, keeping his pledge to act as a “bridge” to a new generation and giving his party ample time to organize a race to succeed him.

Had he done so, Americans wouldn’t have spent the next two years being gaslit relentlessly by the White House about the president’s ability to serve effectively until he’s 86. The spectacle of young Democrats battling over the direction of the left in a competitive primary would have made for a flattering contrast with the grim inevitability of a third Trump coronation on the right. And undecided voters wouldn’t have faced a gut-check decision this fall to hand the presidency to a candidate whom they barely knew and whose agenda remained strategically opaque.

Harris might have benefited from the combat of a primary too, forced to hone her woeful interviewing skills before facing the spotlight of a general election. Either she would have risen to the challenge and become the nominee, or she would have imploded again a la 2019 and some more talented opponent would have advanced to face Trump.

Probably the latter. “Harris would never have been a competitive candidate for her party’s nomination had Biden not made her vice president in the first place,” Jonathan Martin asserted in a piece for Politico on Wednesday. “He picked somebody who had been senator for two years before running for the White House. Her only political grounding was in deep-blue California and a race-to-the-left presidential primary; she had never spent significant time campaigning for votes in Green Bay or Saginaw. And beyond criminal justice issues, she had no real policy expertise.”

Harris was also grievously wounded by the fact that she was, after all, an unpopular president’s No. 2. Literally any other Democratic nominee would have borne less blame for Biden’s failures on inflation and immigration. We can debate the pros and cons of Gavin Newsom or Gretchen Whitmer relative to the vice president, but the plain fact is that either could have run more effectively against the Biden record. And would have: It’s hard to do worse than Harris did when she was confronted about it.

Wherever you land on the question of who would have been the optimal Democratic nominee—and even if you land on Harris herself—there’s no disputing that the party would have benefited in numerous ways from Biden seeing the writing on the wall early and bowing out. The fact that he and his advisers appear to believe, even now, that he might have fared better in his diminished state than Harris did on Tuesday is the most embarrassingly vainglorious thing I’ve ever heard. Obviously he shouldn’t have run again.

But as for whether a different candidate would have defeated Trump? Obviously not, I think.

Long division.

Democrats are wistful today for The Primary That Wasn’t because they feel buyer’s remorse about their nominee. But there’s a reason why a plainly declining Joe Biden drew no serious challengers and why Harris might not have been challenged for the nomination if the president had aborted his campaign in 2022.

Namely, primaries are divisive.

Democrats feared that primarying Biden would divide and demoralize their base and produce a general election landslide for their least favorite Republican, a reprise of Jimmy Carter’s fate in 1980. And many were quietly nervous, I’m sure, of how it would look if a black woman were denied the deference that incumbent vice presidents usually receive as next in line to lead their party. If the sitting VP was knocked off in a competitive primary by a white man, how would women and nonwhite voters have reacted?

The great (and probably only) virtue of Harris’ eleventh-hour “emergency” campaign this year is that she didn’t have to endure a primary. Wrenching disagreements that would have embittered different factions of the party, like Israel and Gaza, were bypassed. Had a battle for the nomination occurred, she and other Democratic candidates would have been dragged to the left on policy in order to appease progressives. (Which is what sank her in her 2019 run, of course.) And that would have made the eventual nominee’s task of running to the center against Trump that much harder.

As it is, Democrats unified behind Harris instantly after she was coronated in July. Her favorability shot up 15 net points almost overnight. If she had performed just a bit better on Tuesday, defeating Trump narrowly, nerds like me would be pointing today to the fact that she was spared the ordeal of a primary as critical to her victory. Both parties would be ruminating about whether a return to the smoke-filled rooms of old might not improve their chances of winning.

We’re also kidding ourselves if we think a primary would have given Democratic candidates carte blanche to criticize Joe Biden’s agenda.

It would have given them some latitude to do so. A Newsom or a Whitmer wouldn’t have carried the “border czar” baggage that Harris bore, for instance. But there were and are loyal Biden supporters within the Democratic base who would have resented seeing their man accused of failure—especially on the economy, as it’s been a sore spot for liberals throughout Biden’s term that strong job numbers and GDP couldn’t quiet complaints about inflation.

A party that remained in denial for more than three years about the state of the president’s health would also have remained in some degree of denial during a primary about the popularity of his agenda. Any Democrat who campaigned aggressively against Biden’s record would have been attacked by some of the president’s fans for carrying water for Republicans and blamed if Trump went on to reelection. Even if an anti-Biden Democrat won the nomination, hard feelings on the left might have lingered and weakened support for that candidate on Election Day.

All of which is to say that a competitive primary might not have put as much distance between Biden and the eventual Democratic nominee as we suppose. In fact, historically, only rarely have American voters handed the presidency to a candidate from the incumbent’s party after the incumbent himself declined to run for reelection.

The last time it happened was 1908, when William Howard Taft replaced Teddy Roosevelt. (Roosevelt would challenge Taft as a third-party candidate in 1912.) Hubert Humphrey nearly managed it in 1968 when Lyndon Johnson stood aside as nominee, but he fell just short in the end. It stands to reason that it seldom occurs. When presidents are popular, they typically run. When they don’t run, it’s usually because they’re so unpopular that they can’t win. And if they’re that unpopular, by definition the electorate is craving dramatic change.

Dramatic change means electing a candidate from the other party, not a different candidate from the president’s party whose politics overlaps nearly entirely with his.

So, yes, Harris carried special baggage as Biden’s running mate. But I don’t think there was anything Gavin Newsom or Gretchen Whitmer could have said to differentiate themselves so dramatically from Biden on matters like inflation and immigration that doing so would have made them a truer “change candidate” than Trump.

Anti-incumbency.

I don’t know what Harris could have said either, if I’m being honest.

Should she have done more populist pandering, such as by attacking big business? I’m open to the argument, but it’s hard to take it seriously after the richest man in the world essentially made himself Trump’s campaign manager and American oligarchs began shining Trump’s shoes with their tongues and Trump won going away anyway.

Was Harris supposed to apologize for Democrats passing the 2021 COVID relief package that helped ignite global inflation? “I’m sorry that we gave you all that extra cash” would have been an interesting stump speech, particularly after Trump himself had approved trillions in COVID aid as president, but presumably not a successful one.

Should she have forcefully repudiated her 2019-era positions on transgenderism? Center-right voters wouldn’t have believed her if she had, I suspect, and voters on the left would have held it against her. And before you say, “That’s why Democrats should have held a primary and nominated someone else,” I’ll say again that a primary would have forced the candidates to pander to progressives on cultural issues. Like, for instance, transgenderism.

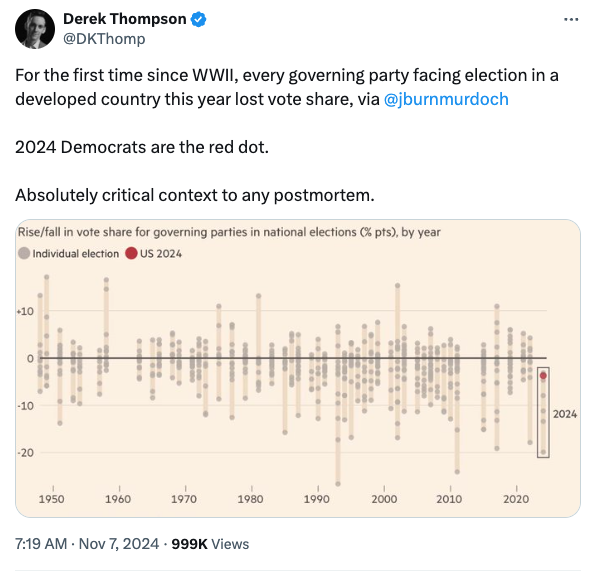

The problem with blaming Harris or Biden or anyone else for Trump’s victory is this: It’s part of a trend. If Democrats blew a winnable race due to some fatal strategic miscue, how do we explain this?

One can argue, I suppose, that America’s governing party was destined to lose vote share this year yet not necessarily destined to lose the election outright, but that’s an awfully tight needle to thread. Biden barely prevailed in the states that decided the election in 2020, remember. Realistically, Harris couldn’t win if she underperformed him, but global anti-incumbent sentiment essentially guaranteed that she would.

And if that’s so, maybe it doesn’t matter who the Democratic nominee was or when Joe Biden dropped out. The cake was baked, perhaps, the moment that America’s liberal party positioned itself amid a populist maelstrom as a bulwark of American institutions against Trump’s autocratic pretensions.

“By portraying herself as the defender and champion of the country’s governing establishment against Donald Trump’s anti-system impulses and diatribes, she placed herself, fatally, on the wrong side of public opinion,” Damon Linker said of Harris. That may be true, but what was the alternative? Should Democrats have gone all-in on destructive burn-it-all-down populism themselves? Should they have nominated Bernie Sanders or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and dived neck-deep into socialism?

If you believe in liberalism, you need at least one of our major parties to advocate for it—and given the state of the American right, there’s only one party that’s willing and able. Linker thinks Democrats might have fared better by characterizing themselves as “responsible reformers” of a system they admit is broken yet maintain is worth saving, but that sounds like very bland oatmeal to me compared to the nihilist populism Trump is offering. Americans don’t want “responsible reform”; they want magic beans and the pleasure of watching their domestic enemies suffer.

“Racial grievances, dissatisfaction with life’s travails (including substance addiction and lack of education), and resentment toward the villainous elites in faraway cities cannot be placated by housing policy or interest-rate cuts,” Tom Nichols wrote on Thursday at The Atlantic, scoffing at the idea that a bit more wonkery might have won Harris the election. That doesn’t describe all Trump voters, but it describes enough of them to have made a majority.

Which brings us back to where we began. Culpability for Trump’s victory lies not with Biden or Harris, but with the unserious, irresponsible, malevolent American voter. Some supported Trump’s fascist vision of government enthusiastically because they believe in it, while others supported it reluctantly because they believe they’ll fare better economically under it. But everyone who cast a ballot for Trump did so because they’re comfortable with the high likelihood that he’ll abuse his powers as president unlike anyone before him.

If there was a catastrophic Democratic strategic error this cycle, that was probably it. Biden and Harris gambled that Americans would never prefer a figure as plainly dangerous as Trump to a “normal” government, even amid the turbulence of inflation. Big mistake. We might literally never recover.

America’s liberal party will now need to consider whether there’s a future in defending liberalism or whether the only way to reclaim a majority is to meet those unserious, irresponsible, malevolent voters where they are. Maybe the only thing that can beat radical right-wing populism is radical left-wing populism, with politics in the future destined to be contested between the tips of the proverbial horseshoe.

Our country’s decline, already in motion, will accelerate. But at least it won’t be boring.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.