Americans are less divided politically than the media likes to pretend.

Yes, it’s a big, diverse electorate, but there are certain opinions we all share. Like this one: I can’t believe the party I hate isn’t getting clobbered in the polls.

From the Liz Cheney left to the Robert F. Kennedy Jr. right, ask any voter at random whether they’re surprised at how close this race is, and my guess is they’ll talk your ear off in exasperation.

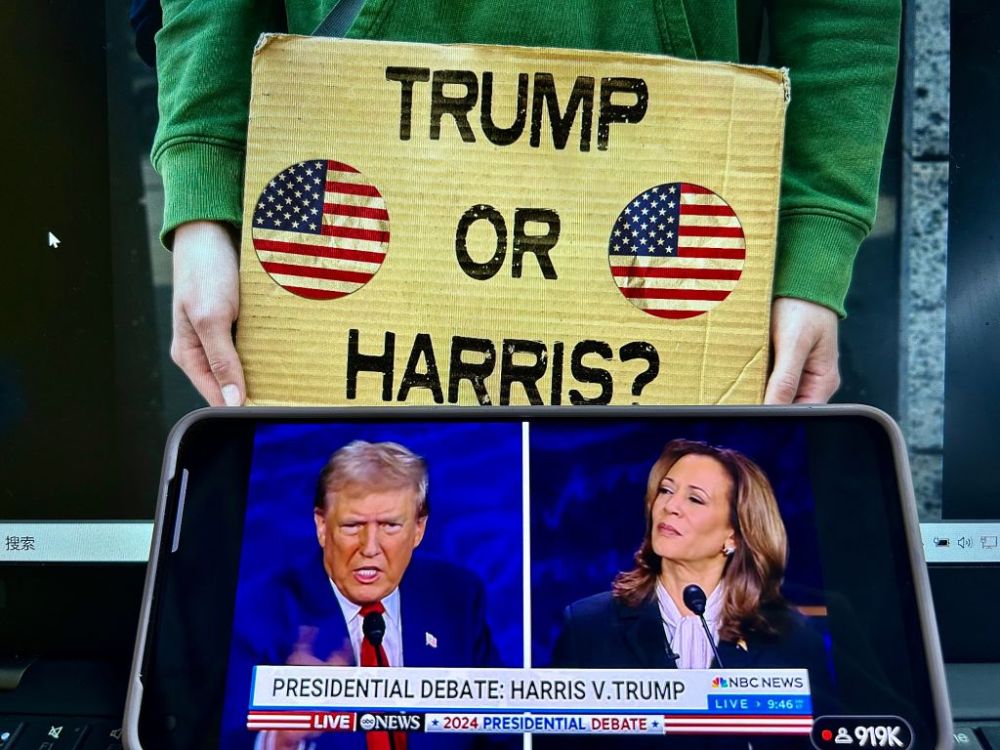

Kamala Harris should be running away with it! You wanted Democrats to ditch the old guy who can’t tie his shoes anymore, right? Well, they did. What more do you want?

Donald Trump should be running away with it! You hate what the old guy who can’t tie his shoes anymore has done to the country, right? Well, now you can send him and his pal Kamala packing. What more do you want?

Each side has a strong case that its party should be teeing up a landslide based on the so-called fundamentals. But the respective fundamentals to which they’re clinging are in tension.

For Republicans, the election is about “political gravity.” The incumbent president is unpopular; inflation was a beast for much of his term; immigration has proceeded largely unchecked on his watch. Add all of that up and the race shouldn’t be close.

For Democrats, the election is about candidate quality. The nominee of the other party is a coup-plotting authoritarian psycho. He was impeached twice in his first term in office and sounds more unhinged now than he did then. Add all of that up and the race shouldn’t be close.

But the race is close, remarkably so by the standards of the past few decades. It’s as if the respective fundamentals on each side have reached a state of equilibrium: Harris can’t break away due to discontent with Biden’s administration, and Trump can’t break away because of the whole “authoritarian psycho” thing.

The irresistible force of political gravity has met the immovable object of candidate quality. Which prevails?

When fundamentals collide.

To properly appreciate how heavily political gravity is weighing on Harris, let your eyes pop at the latest data from Gallup. Across 10 historic predictors of electoral success, Republicans lead on no less than eight. The other two are effectively tied.

Most notably, in every presidential election since 1952 save one, the party that led on the issue that voters deemed most important went on to win the presidency. (The exception, in 1980, saw a tie on that question.) This year, the economy and immigration are the problems commonly cited as “most important.” By a margin of 5 points, Americans believe Republicans will handle them better than Democrats will.

If that’s not enough to alarm Harris supporters, it also turns out that Republicans never once led on party identification in Gallup’s polling of presidential races dating back to 1992—until now, when they’ve bounced out to a 48-45 lead.

These are hurricane-force political winds that Democrats are facing. Is it any wonder that their candidate has tried to remake herself as a staunch centrist with an affinity for certain conservative cultural trappings? If she doesn’t do what little she can to distinguish herself as a “change candidate” relative to Biden, the backlash to his presidency will blow her away.

Trump is making it harder for her, too. He’s fantasized throughout the campaign that America has become an apocalyptic dystopia under Democratic rule, and he has a knack for convincing admirers that his fantasies are reality. He’s not asking voters whether they’re better off now than they were four years ago so much as warning them that Armageddon awaits if he doesn’t win:

Four years ago, based on nothing whatsoever, he persuaded roughly half the country that a mass conspiracy to rig a national election was afoot. With those hurricane-force winds now at his back, he should have little trouble persuading a narrow-ish band of swing voters that the danger of returning Democrats to power is far too great to be risked.

So … why hasn’t he persuaded them?

Not only does Trump trail Harris in national polling, his party is struggling in most of this year’s competitive Senate races. Democratic candidates lead by 4 points or better in Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Arizona. In Ohio, which has been Trump country since 2016, progressive Sherrod Brown is up 3.6 points over Republican Bernie Moreno. Even in Texas, Democrat Colin Allred stands a puncher’s chance of knocking out Ted Cruz.

That simply shouldn’t happen in a national environment in which “political gravity” is crushing the left. The same could be said for 2022, when inflation and residual bitterness over COVID school closures were also supposed to crush the left. Democrats ended up holding onto the Senate and nearly held onto the House. Somehow, they’ve gotten quite good recently at defying “gravity.”

We all know why. Republican voters keep nominating terrible candidates, creating a de facto bunker for Democrats to shelter in as those hurricane winds blow. Arizona, for instance, should have been a gimme Senate victory for Republicans this year after Kyrsten Sinema retired and was replaced on the ballot by far-left Ruben Gallego. Had former Gov. Doug Ducey ended up as the GOP’s nominee in the race, it probably would have been.

But Ducey didn’t run, sparing himself the headache of facing down a Trump-backed Kari Lake challenge in the primary. Lake received the party’s nomination instead. And now she’s getting smoked by Gallego.

Candidate quality matters.

Republicans have ended up in a sort of Catch-22 in swing states in which you can’t win a primary without Trump’s endorsement and, increasingly, can’t win a general election with it. His brand of politics is so toxic to so many centrists that it functions as a sort of anti-gravity device: After four years of Biden, Americans strongly prefer to be governed by Republicans—but not these kinds of Republicans.

So maybe Noah Rothman and Oliver Wiseman are right. Maybe if the GOP had a nominee who wasn’t prone to hawking autographed watches between campaign stops and yammering on television about Haitian migrants barbecuing cats, the anti-gravity effect of poor candidate quality would disappear and Republicans would sweep to victory.

All of this helps explain why Harris and Trump have converged on policy, I think. Each believes that the “fundamental” in the election that favors them will carry them to victory in the end—provided that they don’t let their opponent gain an obvious edge on policy. For Harris, that means talking up border security; for Trump, it means moderation on abortion. And for both, it means lots of maddeningly vague answers on issues where there’s no clear benefit to them from getting specific.

Political gravity will win the election for Trump. Or candidate quality will win the election for Harris. All each needs to do is stand back and let the magic of their favorite “fundamental” happen.

One of them will be wrong. In fact, both are probably wrong.

The problem with fundamentals.

“Political gravity vs. candidate quality” is an elegant framework for understanding the election but it’s too simplistic.

In fact, it’s too simplistic even by the standards of too-simplistic analyses. Say what you will about Allan Lichtman, at least his “keys to the White House” argle-bargle involves 13 factors, not two.

The problem with the framework begins here: Are we sure that a different Republican presidential nominee with supposedly higher “candidate quality” would be outperforming Trump?

Reaganites find comfort in believing that Nikki Haley or Ron DeSantis would be mopping the floor with Harris if only GOP primary voters had had the good sense to nominate them. But where’s the evidence? Trump is polling much better than his party’s Senate candidates are in the swing states I mentioned earlier; his favorable rating is only 8 points underwater, better than Joe Biden’s; and he’s shown an incredible ability over his career to galvanize low-propensity voters who were typically unreachable by more traditional Republicans.

It’s conceivable that, had Trump lost the GOP primary, Harris might be running away with the race as millions of diehard MAGAs opted to boycott the general election in protest. If we define “quality” in terms of a candidate’s grasp of policy and fidelity to civic traditions, then, sure, Trump is freakishly terrible. But if we define it by a candidate’s ability to compete at the polls, he might actually be one of the higher-quality candidates Republicans are capable of fielding.

The “political gravity vs. candidate quality” analysis overlooks another artifact of Trumpism. As he’s gone about remaking the GOP as a populist protectionist party, he’s set in motion a dynamic political realignment among Americans. So dynamic, in fact, that even the pros aren’t sure which elements of it are “real” and which are mirages in the polling.

Will Trump shock Democrats by stealing some of their nonwhite and/or union base out from underneath them on Election Day? Will Harris shock Republicans by holding onto Biden’s edge with older voters and blowing the roof off among college graduates? It may be that the election is thisclose not because voters are agonizing over conflicting fundamentals but because millions are re-examining their policy beliefs as the two parties redefine themselves in real time. In a race as uncertain as that, I wouldn’t expect one candidate or the other to gain a decisive advantage. (Except, perhaps, until the very end.)

If “candidate quality” can’t neatly explain Trump’s polling, though, then “political gravity” likewise can’t neatly explain Harris’.

For one thing, in this case “gravity” isn’t that strong. The S&P 500 reached an all-time high last week; inflation has cooled enough to embolden the Federal Reserve to slash interest rates; the economy has consistently added jobs during Biden’s presidency, albeit at a slower pace this year; even border crossings have plunged lately. Trump wants Americans to believe that another defeat will trigger a thousand years of darkness and the return of Cthulhu, but the evidence just ain’t there.

Insofar as gravity is holding down the Democrats’ presidential nominee this year, it was much stronger when Biden was leading the ticket. The most remarkable aspect of Harris’ candidacy has been her turnaround in favorability, gaining 15 net points in two months. It’s strange to think of a politician who’s barely above water in that metric as “popular” but by modern standards she’s practically America’s sweetheart. Voters in our era routinely dislike national politicians on balance, but not her.

That surely has less to do with her dazzling the electorate with her policy vision than with her declining to offer a vision in the first place, allowing undecideds to treat her as a generic Democrat and a “blank screen” for their own preferences. But either way, she’s successfully defying “gravity”: According to the latest NBC News national poll, it’s Harris rather than Trump who leads when voters are asked which candidate better represents “change.”

Meanwhile, Trump has a “gravity” problem of his own.

Of all the Republicans whom primary voters might have nominated this year, the worst by far to capitalize on the Biden-Harris track record is a man with his own unpopular presidential track record. As relatively unknown quantities, Haley or DeSantis would have been easy bets to top either Democrat on the question of which party is more likely to bring “change.” With Trump leading the ballot, that’s down the toilet. “Change” in this case means restoring a man to the presidency whom Americans fired from the job just four years ago.

Impeachable offenses, incompetence in the face of national crises like COVID, and hourly reminders on social media that the leader of the free world has at least one and probably more serious personality disorders: It’s all back on the menu if Trump wins.

An unpopular ex-president can’t escape the gravity of his own term in office. If the right wanted to fully capitalize on voter dissatisfaction with Biden, it shouldn’t have nominated the one person in the GOP with whom voters also have a history of being dissatisfied.

Just like, if the left wanted to fully capitalize on candidate quality, it probably shouldn’t have nominated someone who struggles to answer questions cogently during interviews with even the friendliest of media. Harris is a better politician than I gave her credit for being when she inherited the nomination from Biden, but it’s not just MAGA media that’s growing frustrated with her habit of hiding the ball on policy.

My fear as we enter October is that the election won’t come down to a clash of fundamentals between political gravity and candidate quality but rather to a choice between the devil Americans know and the one they don’t. Trump led consistently in polling before Biden dropped out because the president couldn’t convince voters that he was up to the job; Harris’ “blank screen” strategy has made her more likable but now risks persuading them that she has the same basic problem as her boss. She’s not up to the job either, not because she’s too old but because she’s an empty suit.

Still, most of us in the commentariat will probably lazily revert to the fundamentals to explain the result in November, whatever that result might be. If Trump wins, political gravity was too powerful for Harris to escape; if Harris wins, Trump was too obnoxious a character for America to reelect. The spin will be irresistible, as there’ll be some truth to it. And so pundits of the left and right will come together around it, just another example of how Americans are less divided politically than the media likes to pretend.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.