I have some good news and some bad news. Let’s start with the good news, because that news is very good. Across the United States, vaccine hesitancy is going down, and it’s going down relatively fast. For example, according to a recently released Pew Research Center survey, 69 percent of Americans have indicated that they’ve either already taken the vaccine or will definitely or probably take it in the future. That’s up from 60 percent last November and way up from the absolute low of 51 percent in September 2020, during the height of the presidential campaign.

And the Pew survey isn’t an outlier. A Yahoo News/YouGov survey also found that willingness to take the vaccine had rebounded to pre-election levels, with 60 percent of registered voters indicating willingness to take the vaccine.

All this is good news, but it needs to continue and accelerate. After all, we don’t really know the magic percentage needed for herd immunity. Yet if the trends can continue, vaccine hesitancy may well be seen as a short-term artifact of an intensely mistrustful and polarized time.

So what’s the bad news? The bad news is that vaccine hesitancy breaks down sharply along partisan and religious lines, and that hesitancy is so profound in white Evangelical communities that it could disrupt the quest for herd immunity. On a partisan basis, white Republicans are among those least likely to take the vaccine. For example, here’s a rather jolting chart from the YouGov poll:

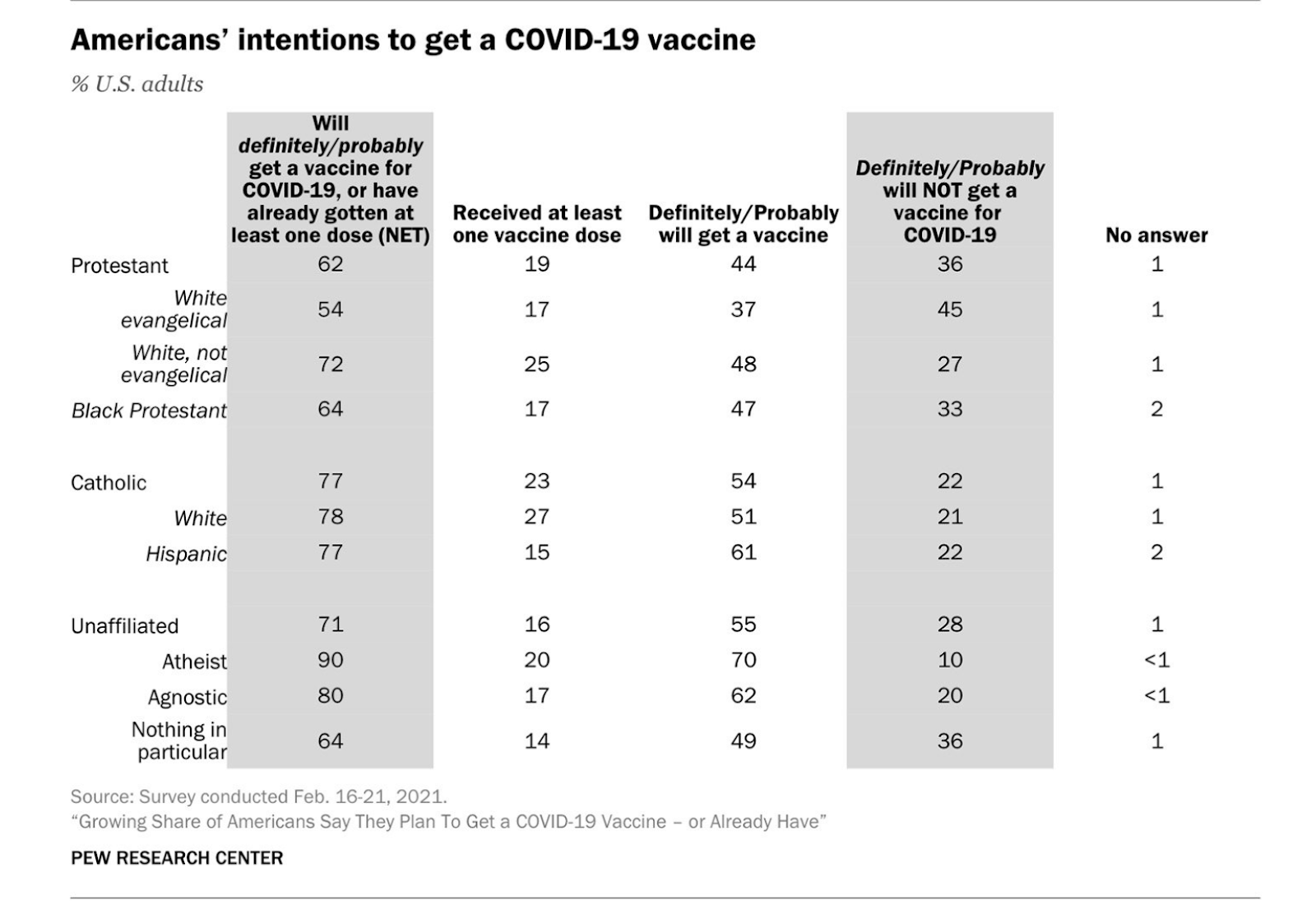

But it gets worse. When you dive into Pew data, you discover that white Evangelicals are less likely to say that they will “definitely” or “probably” take the vaccine than members of any other American religious group, and it’s not even that close.

Only 54 percent of white Evangelicals will “definitely” or “probably” take the vaccine. The next-closest numbers belonged to black Protestants and religiously unaffiliated Americans at 64 percent. By contrast 77 percent of Catholics will take the vaccine and a whopping 90 percent of atheists.

White evangelicals are the least likely to say they should consider the health effects on their community when making a decision to be vaccinated. Only 48% of white evangelicals said they would consider the community health effects “a lot” when deciding to be vaccinated. That compares with 70% of Black Protestants, 65% of Catholics and 68% of unaffiliated Americans.

Given these stark statistics, if there is one thing that readers should take away from this newsletter, it’s that Evangelical vaccine hesitancy is both an information problem and a spiritual problem.

Yes, you can and should flood the zone with more and better information about the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, but we also need to flood the zone with better and more effective spiritual teaching about loving our neighbors and—critically—about trust, faith, and courage.

First, about trust—unless you are in the impossibly tiny minority of people who fully understand the science of the vaccine, we’re all trusting somebody. The question is whom we are trusting and why.

In conversations about the vaccine, I’ve heard a number of people declare, “I’m just less trusting than you.” In reality, these people still trust. They just trust claims and assertions elsewhere—either from a favorite internet voice, a local pastor, or a Bible study full of close friends who have shared counter-cultural health tips and advice for years.

There’s a hostile and condescending way of approaching the different ways we trust. Yes, you can caricature objections and claim that Christians “believe the latest hoax video on PatriotLibertyEagle.net more than the Centers for Disease Control.” But we must instead meet people where they are. We must understand that they’re trusting voices they truly believe love them, care for them, and have their best interests at heart.

Thus, the task for the competing voice—the voice that calls for trust in the CDC and the array of Christian institutions and voices calling for Christians to take the vaccine—is to also speak and live in a way that loves and cares for the people you hope to persuade. Just as you don’t mock someone out of fundamentalism or sneer them out of conspiracies, you can’t berate them into trusting institutions they may perceive to be distant, elitist, and hostile.

Or to put it another way, the entry into the discussion isn’t necessarily, “Mom, you should trust the CDC.” It’s, “Mom, I love you. Trust me. Here’s why I’m getting the vaccine. Here’s why my wife is getting the vaccine.” That’s the conversation that can ultimately bring you to the facts about the virus and the specific reasons why you’re trusting the guidance of the CDC, or of Dr. Francis Collins, the evangelical who heads the National Institutes of Health.

This approach requires us to listen, to hear exactly why someone is concerned and to respond—again, without condescension—to their fears. In that atmosphere of trust and respect, you’ll often find that you can easily allay their concerns.

In this newsletter I’ve often quoted my friend and seminary professor Curtis Chang. He’s put together a video series making the biblical case for Christians to take the vaccine. It’s empathetic and it’s outstanding. It’s designed to be shared with people who express fears and, critically, to equip those who hope to persuade others. For example, here’s his video attempting to answer the question, “Should pro-lifers be pro-vaccine?”

But there’s also a deep, heart-level issue that is besetting elements of the Evangelical church. In part because of grifting culture warriors and in part because of the challenges and temptations of our own fallen nature, millions of Christians have confused selfish defiance with faith and moral courage.

This means, for example, that all too many people believe that the refusal to wear a mask in appropriate settings (indoors or in close proximity to others) is a sign of their personal fearlessness. It’s a declaration either that they have faith that God will protect them from the disease or that they don’t fear the consequences of catching the virus.

Yet it’s well-established that the primary purpose of wearing the mask is to protect those around you more than it is to protect yourselves. When I’m standing next to an unmasked family in church, I’m not thinking they’re brave or bold. I’m seeing instead a tangible disregard for the health and safety of those around them.

Translated into the vaccine setting (and in fact, anti-masking activists are forming alliances with vaccine opponents), many people now see the refusal to take the vaccine as a concrete demonstration of their own courageous assertion of individual autonomy. In reality, they are often yielding to fear—and when they yield to that fear, they are endangering themselves and others.

Thus, the sad consequence of large-scale rejection of the vaccine (especially given the geographic clustering of Evangelical communities) may well be entire counties and towns that suffer needless sickness and death. Even worse, as the Washington Post reports, “The greater the unvaccinated pool, the greater the playing field for the virus to replicate and mutate,” and a “mutation in any location will likely spread everywhere.”

Honestly, we may never persuade a person that a vaccine is “safe” to the point of certainty. We may never persuade a person that he or she can take a vaccine with total confidence. But we can perhaps persuade people that taking risks (or enduring inconvenience) on behalf of others should be a cardinal Christian characteristic.

It should be a key task for Christian leaders to inculcate an ethic that, over time, radically transforms the numbers in the Pew survey, one that places Evangelicals not just at the top of the charts in the willingness to take the vaccine—and thus help bring an end to a deadly plague that has killed more than 500,000 Americans in a single year—but also at the top of the charts in considering the health of the community, of their own neighbors, when making a choice to take a shot or wear a mask.

America’s Evangelical Christian communities are often full of the most radically generous people you’ll ever meet—just watch my Southern Baptist friends activate when a natural disaster strikes. And they’re hardly the only ones. My father-in-law volunteers for the Churches of Christ Disaster Relief Effort, and it’s truly impressive. At the same time, however, in the arena of law and culture, all too many Christians are adopting a posture that declares “Don’t tell me what to do” far more than it asks “How can I serve you?”

One of the truly immense tasks of spiritual formation isn’t so much communicating the truth but preparing a heart to receive the truth and respond accordingly. That’s why the core of the quest to persuade Christians to take the vaccine is personal and spiritual more than it is scientific and informational. If every Christian can read and understand the biblical reality that “greater love has no one than this, that someone lay down his life for his friends,” then we can also understand the lesser love—that sometimes we need to trust, to take a small risk, and take a shot not just for ourselves, but also for our friends, our family, and the country we love.

One more thing …

If you want more content to share and discuss with friends and family about the vaccine, this video from Curtis is key to the entire project of persuasion. It’s about safety, but it’s also about much more.

You can watch all the videos at www.ChristiansAndTheVaccine.com.

One last thing …

Speaking of love and sacrifice, this new song from NeedToBreathe about Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane is powerful. Thank you to the Dispatcher who sent it my way. Enjoy:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.