Hi,

Harry Anderson, the guy from the original Night Court, was a great stand-up comedian and magician. He had this bit where he’d juggle weird stuff, including an ax. When he took out the ax he’d say something like, “This is George Washington’s ax. The very one he used to chop down that cherry tree. Unfortunately, the blade had to be replaced years ago. And just the other day the handle broke so I had to replace that too. … But in principle, this is George Washington’s ax.”

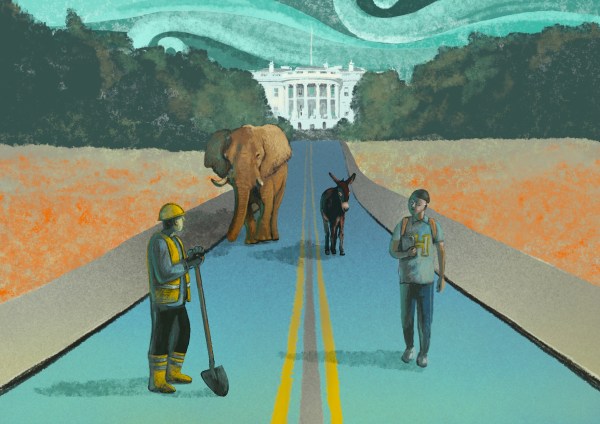

That came to mind when I was texting with The Dispatch’s executive editor, Declan Garvey, this morning. He told me that he always wanted to write a piece about the GOP as the Ship of Theseus, also known as Theseus’ Paradox. The idea is that a thing ceases to be a thing if it’s completely changed over time. Here’s how Wikipedia explains it:

In Greek mythology, Theseus, the mythical king of the city of Athens, rescued the city’s children from King Minos after slaying the minotaur and then escaped onto a ship going to Delos. Each year, the Athenians would commemorate this event by taking the ship on a pilgrimage to Delos to honor Apollo. A question was raised by ancient philosophers: After several hundreds of years of maintenance, if each individual piece of the Ship of Theseus were replaced, one after the other, was it still the same ship?

While I think these philosophical issues are really fun to noodle, particularly when applied to concepts of human identity, I want to talk about Declan’s idea (which he gave me permission to steal).

Let’s start by thinking about the best-case and worst-case scenarios for a Donald Trump or Kamala Harris presidency.

This is not something I normally do. In my experience the best-case and worst-case scenarios tend to be the most unlikely ones. And, if you spend your life making decisions based on avoiding being eaten by sharks or on definitely winning the Powerball this weekend, you’re going to make a lot of poor decisions. So, let’s rule out the extreme scenarios and stick with the fairly plausible ones. That means ruling out most of the stuff you hear on cable about fascist dictatorships, America-as-Venezuela, and global thermonuclear war.

This is still a harder exercise than it seems at first, because success and failure are in the eye of the beholder to a certain extent. Think of it this way: Ideologues and partisans have different agendas and interests. I’ve found that this is one of the hardest distinctions to explain to people because the two categories are essentially platonic, without many flesh-and-blood examples in real life. We often treat hyper-partisans and hyper-ideologues as synonymous types, in part because most extreme ideologues are also extreme partisans, and they don’t see much of a difference. But there are exceptions. The best illustration of the point would be (some) libertarians. Libertarians have feet in both the left and right, so they aren’t completely at home in either. Thus, the best libertarians tend to focus more on moving policy in their direction. If the Democrats are libertarian on X they’ll root for Democrats on X. If the Republicans are libertarian on Y, they’ll lend aid and comfort to Republicans on Y. In other words, libertarians—at least the ones I have in mind—are very ideological but not very partisan.

There used to be all sorts of issues that worked this way. The National Rifle Association used to give a lot of money to pro-Second Amendment Democrats. There used to be a lot of pro-abortion rights Republicans. But the alchemy of the Big Sort and polarization have transmogrified the parties.

Which is why this kind of distinction is very, very hard to find on today’s left and right. If Republicans are for it, that’s conservative. If conservatives are for it, that’s the Republican position. Ditto for the left and Democrats. Obviously, there are some specific issues that divide partisans internally, but I can’t think of any that would cause a serious left-winger to root for Republicans or a serious right-winger to vote for Democrats. Except of course, for the issue of Donald Trump and his fitness for office. People who say Liz Cheney isn’t conservative because she’s endorsed Kamala Harris are a perfect illustration of this phenomenon. A purely strategic decision that is bad for Republicans is perceived as a rejection of conservatism qua conservatism. I think that’s ridiculous. But lots of very smart people, including many of my friends, see it that way. But let’s put that aside for the moment.

It’s instructive that for a middle-of-the-road type who doesn’t much care about partisan politics or ideological agendas, the best-case scenarios for both presidencies actually look pretty similar: a very good economy, no war, a lot less drama, and maybe some concrete success at getting the border and our fiscal house in order. For people tuned out of politics, Trump’s presidency looks pretty good in retrospect to them. There was a lot of drama—but, again, they tuned a lot of that out—but we had a good economy (until COVID) and little war (for some reason, a lot of people forget that there were more American troops in combat under Trump—in Afghanistan, against ISIS, etc.— than there have been under Joe Biden. And, while final stats aren’t available yet, it looks like more Americans will have died from hostile action under Trump than under Biden). Nostalgia for high wage growth and low inflation is not irrational during a time of high inflation.

Meanwhile, the best-case scenarios for hyper-partisans and ideologues are like inverse mirror images. If Trump wins, the best-case scenario for the ultra-MAGA crowd looks a lot like the worst-case scenario for the left. Stephen Miller hits the ground running on Project 2025, Trump crushes the left, dismantles DEI and climate-change stuff, and deports millions of migrants at gunpoint. Maybe he even manages to convince Congress to pull us out of NATO. If Harris wins, the best-case scenario for the left is the worst case for the right. She immediately reverts to the Kamala Harris of 2019, writes a blank check for gender “therapy,” blows billions on globalist alliances, packs the Supreme Court, abolishes the legislative filibuster, and triples down on the Green New Deal.

Now, I should say, I think both of these scenarios are very unlikely for largely the same reasons. Neither Trump nor Harris are particularly good politicians or administrators. And the more they pursue the brass ring of the best-case scenario desired by their biggest fans, the more opposition and roadblocks they will encounter.

What’s interesting to me is most of my tribe of conservatives who are going to vote for Trump don’t actually want him to succeed on the full MAGA agenda. They don’t want to pull out of NATO. They may want to see a bunch of people deported—I do too—but they understand that a massive domestic military operation is operationally, politically, and in some cases, morally unfeasible. But they also roll their eyes at the idea that Trump will do many of the things that anti-Trump people worry about. Like the normies, they point at the first Trump term and say we’ll get more of the same, which is much better than what we’d get under Harris. In other words, they believe the worst-case scenarios about Harris but reject the worst-case scenarios about Trump.

Now, I am extremely skeptical about Trump II being a replay of Trump I (I also disagree with those conservatives about how Trump I was simply a matter of “mean tweets” and the like). He’s angrier, weirder, and more confident now. The major lesson he learned from his presidency is to surround himself with true believers, loyalists, and enablers. Trump won’t defer to the John Kellys, Paul Ryans, and Mitch McConnells, because they won’t be there to talk him out of stupid or dangerous ideas. He’ll be surrounded by people who will respond to his every impulse as if it were oracular genius. Perhaps not entirely on foreign policy: I generally trust Mike Pompeo and Tom Cotton not to be idiots or whack jobs. I have no such confidence in, say, Kash Patel. I think it’s preposterous to believe Trump will be talked out of protectionism and industrial policy.

But I could be wrong. Where I am more confident, however, is that their vision of the worst-case Harris presidency is wrong. Unlike Trump, Harris will be up for reelection. The same calculations driving her to the center now would remain in effect once she’s elected. Will she do bad and dumb things? Of course. But even if the Democrats win both the House and the Senate, she won’t have the kinds of majorities that Barack Obama enjoyed. Indeed, it seems unlikely the Democrats will take the Senate, which would mean court-packing, the Green New Deal, etc., would be impossible, even if she tried to pursue such things. People forget that though Obama was a very talented politician, once he lost Congress he was pretty ineffectual. Sure, he did some stuff with his mighty “pen and phone,” but a lot of that stuff was erased after Trump took office. Harris would enter the White House a worse politician without congressional majorities, and much, much, less personal popularity.

It’s weird. Partisan Republicans love to talk about what a bad politician she is. They talk about how she gives terrible interviews and can’t explain policies. Her inappropriate laughing makes people squirm. And they’re right. She sounds like she cribbed her favorite sound bites from greeting cards and throw pillows at a healing crystal gift shop in Sonoma. But for some reason they think that once she’s president, she’ll be unstoppable?

I think the most likely scenario is that Harris would be a modest failure. Her best accomplishment would be fulfilled the moment she—not Trump—took the oath of office.

And here’s where I think the distinction between principled ideologues and partisans becomes most relevant. For partisans, winning is always the highest priority. It’s zero-sum. But if you don’t care much about partisan victories, you can see how partisan defeats can be good in the long run. And not just good for your agenda, but for parties, too. Was it good for the GOP that Herbert Hoover was in office when the stock market crashed? No. Was it good for conservatism? Hell no. But for the crash you don’t get FDR and the New Deal. In other words, a 1928 defeat for the GOP would have been good for it and conservatism in the long run.

Biden was going to lose badly because he decided to run up ideological victories—to go “bigger than Obama” and push a new New Deal—and it blew up in his face. He was going to get hit with inflation no matter what, but he made it worse by sticking to his “legacy”-padding ideological agenda. If Biden had followed his political interest and served as the moderate normalcy candidate he ran as, he might have been able to stay on the ticket—and win—despite his infirmity.

If Harris wins it will be an obvious loss for the GOP in 2024 because of that zero-sum thing. But a weak and unpopular Harris presidency would quite plausibly be better for the GOP in the long run. After all, the Obama presidency was great for the GOP (as was the Carter presidency). Obama’s presidency wiped out moderate Democrats across the country. More than a thousand elected Democrats lost their jobs during his tenure, with state legislatures and statehouses flipping for Republicans. And his presidency—and Hillary Clinton’s candidacy—made Trump’s victory possible.

Now, if Harris actually governs as a moderate, triangulating like Bill Clinton and hugging the center, she might be more successful. She might even be reelected. That would be bad for Republicans. But would it actually be bad for conservatism? In some ways, perhaps. But in some ways this would be a victory for conservatives because it would move the Democratic Party rightward, which would move the center of gravity of American politics rightward. And that’s what conservatives are supposed to care about more than mere partisan success. Moving the Overton window rightward would mean that more left-wing ideas would be considered fringe and beyond the pale of the politically acceptable. One of the biggest victories conservatives ever scored in my lifetime was symbolized by Bill Clinton declaring, “The era of big government is over.” When he signed welfare reform, it was bad for Republicans—because it arguably guaranteed his reelection—but it was a huge victory for conservative governance, in the same way that Republican Dwight Eisenhower’s acceptance of the New Deal was arguably the left’s greatest victory of the 20th century.

Do I think Harris will actually govern like that? Not really. Though I think odds are good she’ll try here and there. She certainly knows that she’ll be doomed if she ignores immigration and the border.

The point is that the most likely best- and worst-case scenarios for a Harris presidency just aren’t that scary and have much more upside than the catastrophists claim.

So, what does any of this have to do with the Ship of Theseus?

Well, that’s my most plausible worst-case scenario. I am not dismissing the concerns of people who think Trump will try to be an authoritarian strong man to pad his own conception of a legacy. I don’t think he’d be a Hitler or Mussolini—they were much cannier for starters, and America is not early 20th century Germany or Italy. I think he’s much closer to a Juan Perón type anyway. Perón was a bad dude, but he was more interested in seeming like fascist strongman than actually doing the hard and ugly stuff. But we’re not mid-century Argentina either.

But what I think is the most plausible—nay, likely—worst-case scenario for a Trump presidency is that current trends continue and accelerate. The definition of what it means to be a conservative has morphed before my eyes in the last decade. I grow weary having to offer examples, but it’s a necessary chore. Conservatives used to be adamant to the point of prudish sanctimony about the importance of good character. Now, to even have a problem with Trump’s boasting of sexual assault—never mind jury verdicts about the same—is to declare yourself a weak-willed cuck and snob. Free markets and free trade used to at least be ideals, even if political necessity sometimes required compromise. But the idea that planners and politicians were smarter than the market was anathema to a movement dedicated to Burke, Smith, Hayek, Sowell, Friedman, Buckley, et al. Now, “industrial policy, done right”—in Marco Rubio’s words—is all the rage. Donald Trump thinks he should pick winners and losers in the economy—from tariffs to overruling the Federal Reserve. Strong alliances were the bedrock of conservative foreign policy from Eisenhower to Bush. Defending, even if only sometimes rhetorically, freedom and democracy and denouncing tyranny was conservative dogma. Trump belittles and mocks democratic allies while fawning over strongmen everywhere. Most of all, the granite spine of modern American conservatism was fidelity to the U.S. Constitution. Donald Trump called for terminating the Constitution as needed to reinstall himself in the Oval Office based on a provable and proven lie about the election being stolen.

I could go on. But you get the point. Trump’s most committed defenders celebrate all of this and call it conservatism. But far more people simply line up like the monkeys who see, hear, and speak no evil because in this partisan climate the only abiding political evil is to speak ill of Trump, at least in public. You can still do it in private, but it’s getting harder in part because more and more people have converted. But it’s also harder because many of the people who know the truth still don’t want to hear the truth as they shovel dirt on conservatism’s grave. They don’t enjoy emptying their shovels, but they do it in the spirit of “let’s get this unpleasantness over with. It’s got to be done to beat Kamala Harris. We’ll dig up and clean off conservatism later.”

But conservatism isn’t some gold religious icon you hide from marauders until they leave. A whole generation of young, self-described conservatives think all of this is normal, that they are real conservatives. The last thing they’re interested in is digging up the old idols and putting them back on the altars. They like the new religion. They make money and get attention from the new faith. And so do the new priests who preach it.

Taking the long view, I do think this country is doomed without conservatism. No, I don’t mean in the apocalyptic sense I routinely decry. I mean that what makes this country great needs to be conserved. The new conservatism, despite all of its Make America Great Again rhetorical pabulum, isn’t about conserving—preserving—what is great about America, it’s about replacing conservatism with a kind of right-wing statism, which is just a fancy way of saying conventional right-wing populist nationalism. The change is sudden if you stand opposed to it, but for the partisans, it’s gradual and piecemeal enough that they don’t notice it—or choose not to.

I’m reminded of a story I first read about in Michael Burleigh’s outstanding The Third Reich: A New History (which I wrote about in Liberal Fascism). In 1937 the German Social Democratic Party, operating in exile in Prague, enlisted a spy to report from Germany on Nazi progress. The reporter, working in secret, offered a crucial insight into what the Nazis were really up to. The National Socialist German Workers’ Party was constructing a new religion, a “counter-church,” complete with its own priests, dogmas, holidays, rituals, and rites. The agent used a brilliant metaphor to explain the Nazi effort. The counter-church was being built like a new railway bridge. When you build a new bridge, you can’t just tear down the old one willy-nilly. Traffic and commerce will be snarled. The public will protest. Instead, you need to slowly but surely replace the bridge over time. Swap out an old bolt for a new one. Quietly switch the ancient beams for fresh ones, and one day you will have a completely different structure and barely anyone will have noticed.

No, the new conservatism isn’t Nazism, even taking Trump’s increasingly grotesque rhetoric about vermin and enemies within. But it isn’t conservatism as I know it, either. And for me the most plausible worst-case scenario is that a second Trump presidency will spell the completion of a new Theseus’ Ship of “conservatism.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.