Campaign Quick Hits

Results in the Texas 6th: The votes are in, and … it’s headed to a runoff. Of course, with 23 candidates on the ballot, that was a foregone conclusion. The widow of Rep. Ron Wright, longtime GOP activist Susan Wright, took the top spot, which was expected. But despite a lot of puffery in the media about how the district was trending away from Republicans, it was Democrats who got a wake up call: The second person headed into the runoff was not the DCCC’s Jana Sanchez, but another Republican, state Rep. Jake Ellzey. As FiveThirtyEight reported, Ellzey was the “top fundraiser from either party but also had more money in his campaign coffers than any other candidate.”

Of course, if I had asked you pre-2016 who would advance out of a 23-person field, the good money would have been on the widow of the officeholder (who shares a name) and the top fundraiser. No doubt some will argue this means doom and gloom for the Adam Kizinger “disavow Trump” Republicans, whose candidate finished with barely 1,000 votes, and it may. But I’d say their bigger problem was picking a candidate with zero name ID in the district, a bland résumé, and very little money to raise his profile in time. Again, pre-2016, it would have been a cliché that national media is no substitute for people in your district knowing who you are and feeling comfortable with you.

So does that mean we are returning to pre-2016 political realities? I think you can make a good argument that there was a singular exception to the rules of political gravity that nobody else has been able to replicate … and that, at least, held true in this race.

The point: The Texas-6th will be held by a Republican, giving the Democrats no breathing room heading into 2022 with a five-seat majority in the House.

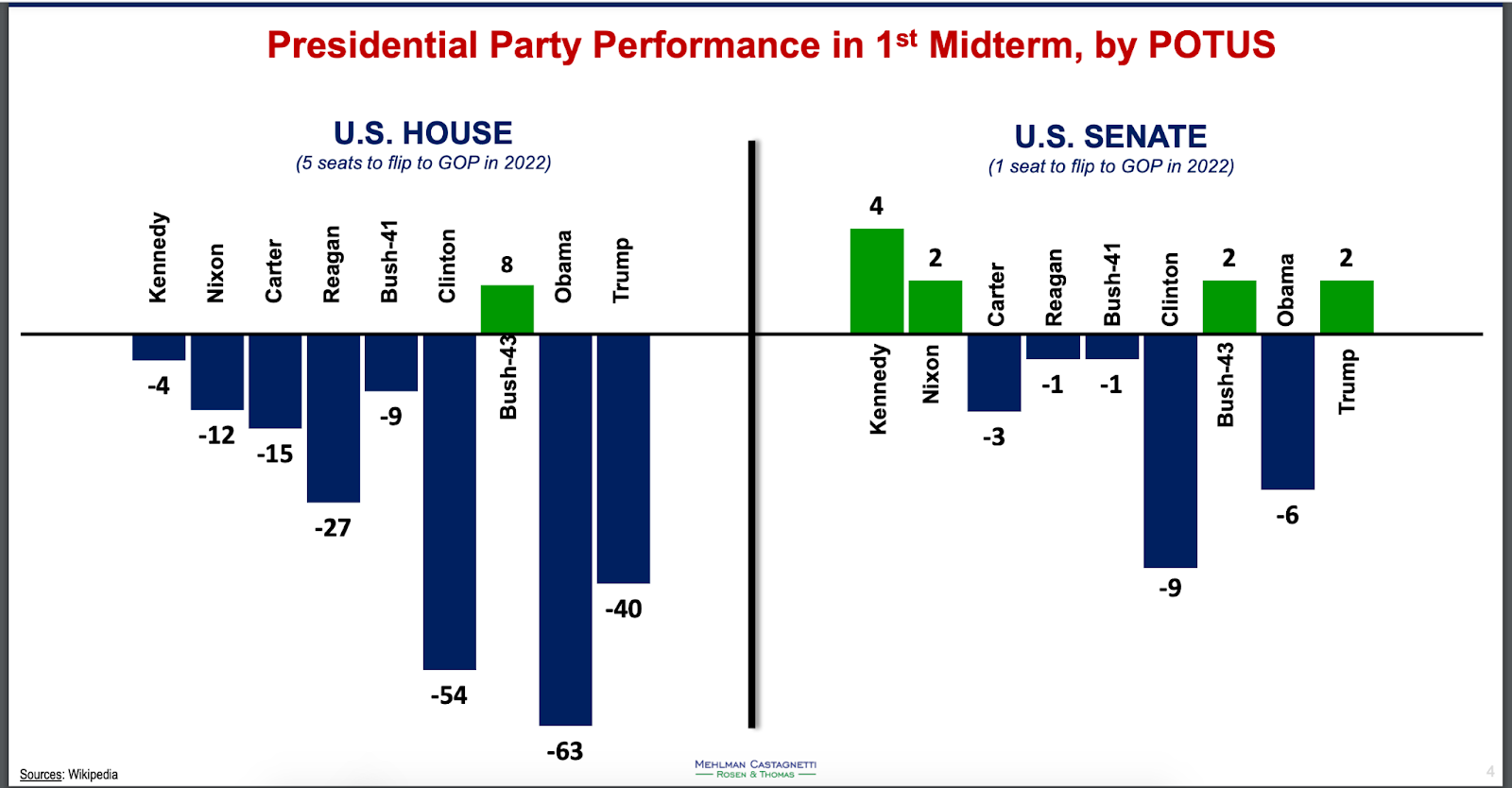

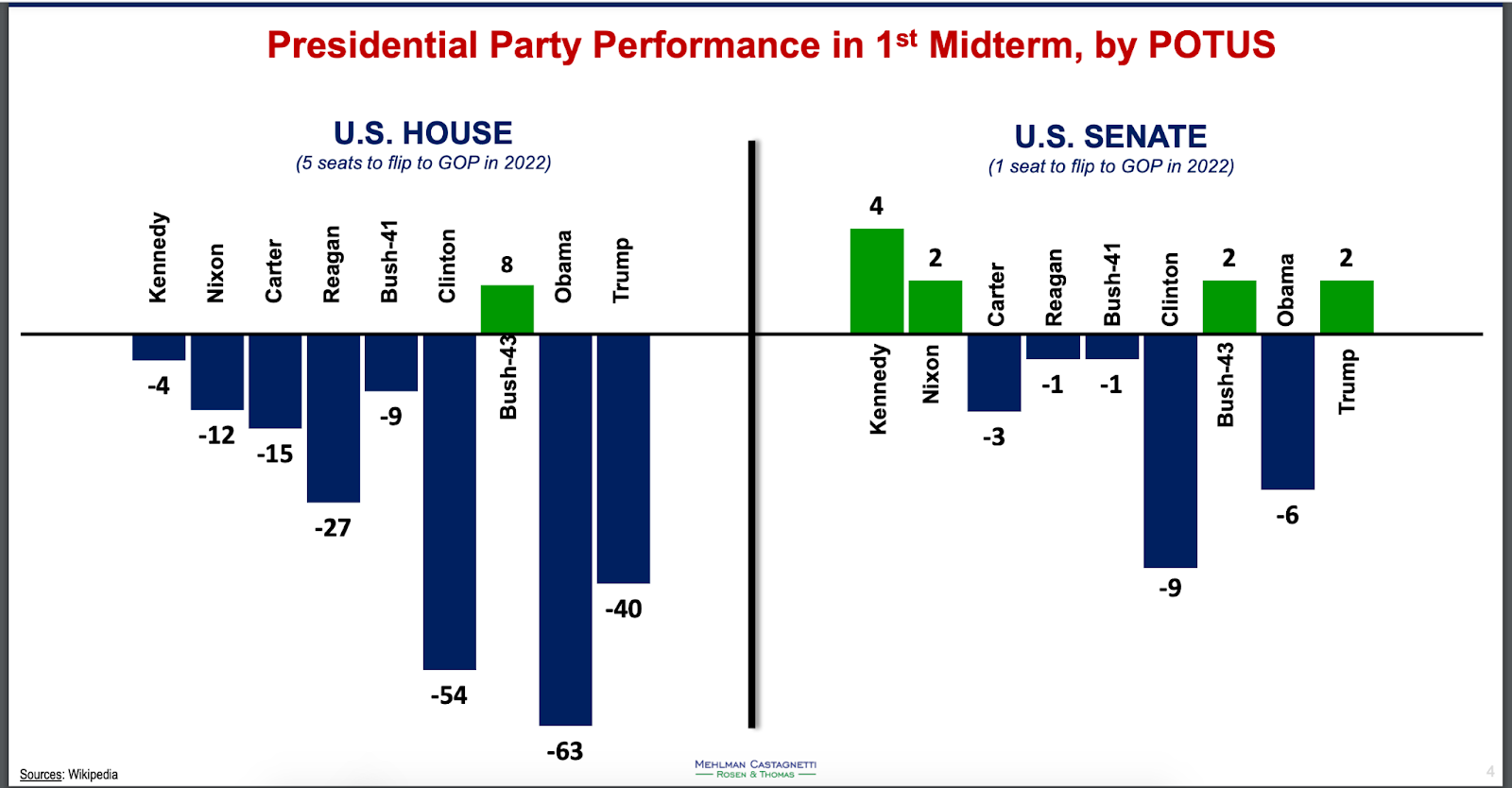

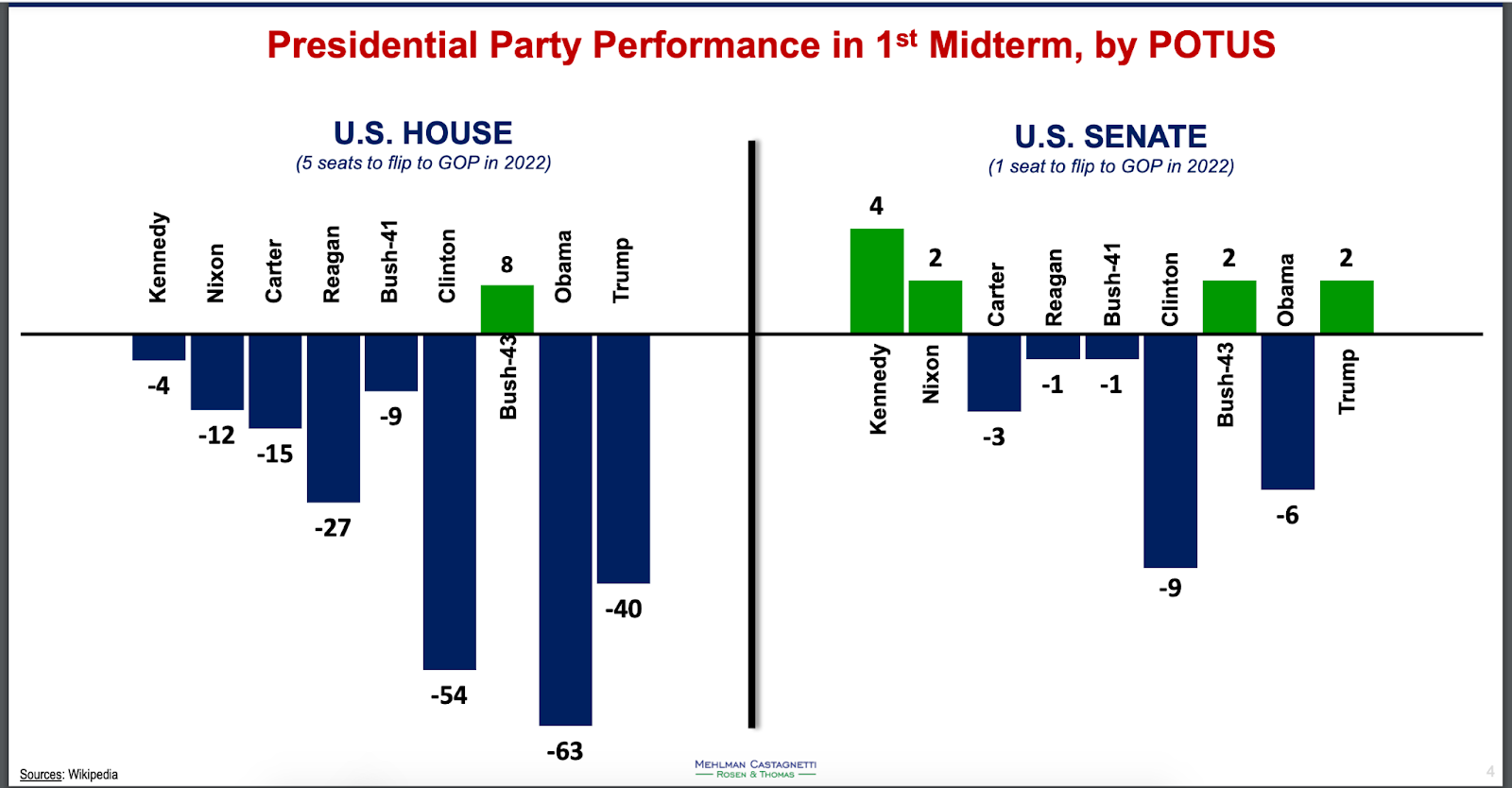

Three Midterms Graphics to Chew On

Courtesy of strategist Bruce Mehlman:

Major Donors Are Dead, Long Live Major Donors

I was thinking about this quote that I included in last week’s edition of The Sweep from Richard Hanania: “49.1% of all Americans cast a ballot in 2020, compared to 2.9% who cared enough to actually give money to one side or the other.”

That’s it! That’s the whole explanation for why we are where we are. Well, at least it’s half of it. See, my theory has long been that everything that is playing out currently in our politics—the fecklessness of Congress, the disintegration of the Republican Party, and the negative polarization on both sides—is all an unintended consequence of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (aka BCRA, aka McCain–Feingold).

I could literally write an entire thesis paper on this topic but let me give you the BLUF:

The ban on “soft money” weakened the national parties.

The low limits on individual federal donations disincentivized major donor programs and incentivized the money to come from elsewhere.

We’ll leave No. 1 for another day—it’s important, but lots of other people have written about it. But No. 2 hasn’t gotten nearly its due. So let’s break it down a little.

The current limit that an individual can give to a federal campaign is $2,900 toward the general election. So as a candidate you’ve got two problems: First, there aren’t that many people in the country who have that level of disposable income. Second, $2,900 is a small drop in the bucket compared to what you need to run a federal race at this point. The contribution limit was indexed to inflation—but not the inflation of campaign expenditures. My first campaign was in 2002 and the limit was $2,000. But the range for contributions from individuals in the top 50 House races in 2002 was $1 million to $3 million. In 2020, it was $5 million to $28 million. So while the donation limit is 1.5 times higher, the amount of money you need to raise to stay competitive is six to nine times more. What is a candidate to do?

To start, you try having outside groups without limits. There’s a reason Citizens United came to the Supreme Court for relief in 2010 and not 1995. There was no way for them to get the money to their candidate, and there was no way they weren’t going to spend the money to help their candidate. Thus, super PACs were born, and millions and millions of unlimited dollars started pouring into groups that are allowed to spend the money on electioneering activities as long as they don’t ask the candidate how they should spend it. But as I wrote last year on Citizens United’s 10th anniversary, super PACs are pretty terrible and aren’t nearly as effective as direct spending by the candidate.

So while that money is being lit on fire, campaigns needed a new plan. Ben Carson wasn’t the first to figure this out—but he did get a lot of attention for it. Ben Carson raised $20.8 million in the third quarter of 2015 … and he spent more than $11 million raising it. To put it in political operative terms, he was spending 54 cents to raise each dollar. At the time, that seemed insane. When asked whether that kind of burn rate was sustainable (Scott Walker and Tim Pawlenty both learned about burn rates the hard way, dropping out of their races early after running out of money), Carson spokesman Doug Watts replied, “It’s not only sustainable, it’s strategic and it’s profitable.” He was right.

Fast forward to now, and campaigns on both sides have gutted their “major donor programs” and beefed up their online and digital fundraising. The cost per dollar raised is substantially higher, but it doesn’t take any of the candidate’s time—a campaign’s most valuable resource—and the candidate doesn’t have to dial for dollars for eight hours a day, a task that very few candidates are willing to do without grumbling, procrastinating, or other tactics used by teenagers to get out of geometry proofs.

But remember what Hanania said. Only 3 percent of voters are ever going to give to a candidate (and that number gets lower the lower down the ballot you go). So how do you reach them? And how do you motivate them? Outrage.

When Mitt Romney got in trouble for his 47 percent comment in 2012, he was speaking at a major donor event. Up to that point, it was de rigueur for a candidate to say one thing in public and have a totally different message to their major donors. But online fundraising doesn’t require that at all. In fact, it is the opposite. Everything is an opportunity to raise online dollars. So everything the candidate does and says needs to be geared toward that 3 percent. And, as you can guess, they don’t care about the same stuff as the other 97 percent who don’t give.

As a result, Congress has no incentive to legislate (in fact, not legislating is better to keep the problems alive … think immigration reform), the national parties are of minimum help because they are drawing from the same pool as candidates (I drink your milkshake), and candidates are best served by stoking the outrage by doubling down on the culture war on both sides.

So there you have it. I am a Burkean minimalist because of the 17th Amendment and BCRA. Both sounded so good in theory, but beware the unforeseeable consequences that await the best-laid intentions in the tall grass.

Chris is back with his wit and wisdom, and it’s Mike Pence’s turn in the barrel:

How to Run For President (While Really Trying)

There’s encouraging a little presidential speculation with a whisper campaign, and then there’s scheduling a trip to New Hampshire right after giving a big speech in South Carolina. Former Vice President Mike Pence is forgoing the whispers and grabbing the bullhorn as he gets ready to head to the Granite State next month to speak at the annual Lincoln-Reagan dinner in the state’s most electorally important county, Hillsborough.

Pence chose a group of South Carolina social conservatives, Palmetto Family, last week for his first major public remarks since January 6, when a mob of pro-Trump rioters tried to keep him from certifying the results of the 2020 election. He also spoke to a gathering of hundreds of pastors and made a campaign-style stop at a South Carolina medical school to talk about coronavirus response—a convenient way to highlight his successes leading the White House pandemic response team.

Pence has scheduled a high-profile slate of speeches, appearances, and fundraising events in the coming weeks, and his team promises that he will frequently hit the trail in support of midterm candidates. He’s got a book in the works, and he’s even launching a podcast. It’s safe to say that he’s running—or at least he wants to. What we don’t know is whether his timing is right.

I have been bullish on Pence’s chances for the GOP nomination ever since the chaotic Capitol raid. As the former vice president for a divisive, unpopular commander in chief, Pence didn’t have much of a chance for 2024. He was so obsequiously devoted to Donald Trump and his “broad-shouldered leadership” that it seemed unlikely Pence could get enough mainstream support to push through to the nomination. But because of his milquetoast persona and Sunday-school teacher vibe, neither could he tap in to the cult of personality among Trump’s hard-core supporters. He was too Trumpy to win over traditional Republicans, but not Trumpy enough for the MAGA stans. When Trump turned on Pence and sent a mob of berserkers to go try to stop him from filling his constitutional duty, however, the former president gave his No. 2 a massive political gift.

It’s certainly true that Pence’s decision to do his job will kill any chance of winning over the hardcore Trump lovers, but he probably wasn’t going to score well with them anyway. And there will be lots of Trump wannabes dividing up that share of the vote. But now, unlike his potential mainstream competitors Nikki Haley and Mike Pompeo, Pence has shown that he was willing to defy Trump when it counted. The fact that he could do so without having to make a show of it is all the better for his chances. For a party that will surely be exhausted by the fight over Trumpism, Pence could represent the kind of bland compromise that voters may be seeking. If a former vice president could win the Democratic nomination by being the consensus compromise choice, why couldn’t the Republicans pull the same trick?

What’s less clear is how Pence’s candidacy will wear over time. His incipient run will no doubt anger Trump, who is busy trying to maintain his grip on the GOP from his gilded bunker at Mar-a-Lago. Pence did as much as anyone to put the lie to Trump’s loony claims in service of his efforts to steal the 2020 election. Trump, eagerly cruel and enthusiastically petty, can hardly let the offense go unpunished. Maybe the thinking from Pence and his very savvy strategist, Marc Short, is that it’s better to draw that fight out early so it’s old news by 2023. Or maybe they just don’t think they can afford to start raising money and locking up support in what will be a very crowded field. Whatever the reason, we’ll soon find out whether the former Veep can find a way to survive and advance in a party still terrified of his former boss.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.