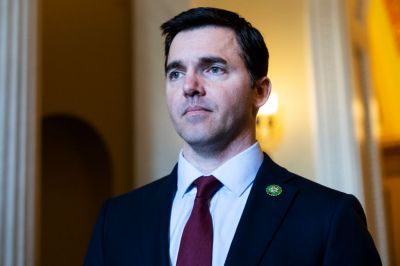

North Carolina Rep. Jeff Jackson, a National Guard officer and former state senator, now represents the state’s new 14th Congressional District, which covers most of the city of Charlotte and some of its suburbs. A member of the Armed Services Committee and the Science, Space, and Technology Committee, Jackson recently introduced a bipartisan bill with three other members to keep China from remotely accessing American technology to develop its own artificial intelligence capabilities.

In the interview below we discussed his first seven months on the job, including Congress’ approach to social media and artificial intelligence, the National Defense Authorization Act, and his commitment to communicating directly with his constituents. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You worked in the North Carolina state legislature before. How does Congress compare?

When I was in the state legislature and I walked off the Senate floor, there were never any reporters there to greet me. When I step off the House floor, there are like 30 reporters with microphones out. And that’s a very different experience—the level of press attention that we get on a daily basis is just categorically different. There are a few issues that play a much larger role at the federal level than they do on the state level. I’m on the Armed Services Committee, and that would be one clear example.

You have a huge following on TikTok. But you’re also the only member of Congress I’ve heard of who is posting on Substack. How have you landed on that as a strategy for communicating to constituents and the public?

I’m big on reaching people directly. In my experience, not many people want to hear what a political party has to say; they want to hear from a person. So my approach is to be a person who speaks directly to them with respect, and over time, you’ll earn that respect back. I use TikTok because it’s a big way to reach people directly—but it’s the same reason I use other social media platforms and the same reason I use Substack. TikTok just happens to be the biggest at the moment, but I’m sure that will change—when I started, it used to be mainly about Twitter and Facebook, but that’s shifted. I can always tell, by the way, that I’m reaching the younger audience on TikTok by the extent of the emoji use in the comments.

TikTok’s gotten a lot of attention from members of Congress lately as potentially a national security threat given the ties with China, and now it’s banned from government devices. Are you concerned?

I think the concerns are real. I’ve read what FBI Director Wray thinks about it, and I take his assessment seriously. I agree with not allowing TikTok on government phones. I keep the app on a nongovernment phone, and that phone only has one app on it. And that’s TikTok.

Right before recess, the Senate Commerce Committee advanced COPPA 2.0 and KOSA, trying to address potential harms of the internet and social media for kids and teens. You’re both a parent and a member of Congress. What’s the role of parents and families versus policymakers?

Our 15-year-old’s big thing is Snapchat. I checked his phone one day and he had received over 200 notifications on Snapchat. Apparently, people his age don’t text, they don’t email, they don’t call—they use Snapchat. And I just thought, How can you get anything done with a phone beeping 200 times a day? Have we subjected our children to a social media environment where they’re just going to be permanently distracted and they’re never going to develop an ability to focus? We’re just running this huge experiment on our kids. And as easy as it is to agree on the problem, it becomes a lot harder when you start drafting solutions. So I’ve taken a look at those bills on the Senate side, although not in detail. I think there’s some good stuff in there; I think there are some problems in there. But I just wish that we had had this conversation more seriously 10 years ago. So much of the genie is out of the bottle at this point. And frankly, this kind of relates to my concern with AI. I think the big concern with AI isn’t that we don’t get the response quite right. It’s that we end up doing what we did with social media, which is to effectively do nothing until it’s too late.

On that note, what have you been learning about AI?

We decided several months ago to make this a focal point for our office. And we started with making sure that we were well informed. We sort of undertook a broad-based self-education, and we arranged conversations with a lot of different leaders in the field—dozens of conversations. And through that we were able to find our first decent idea in this space, which is a bill we’ve already filed. But I think in truth, that’s a pretty small bill. I hope and believe it will be uncontroversial.

We’re working on a second bill that attempts to move past this conversation of frameworks and guidelines. As a starting point, our idea is to say, “Look, let’s make it harder for this technology to be used to create new biological or cryptological weapons.” One of the things that we heard over and over again in our conversations is that there’s a greater threat there than people fully understand. So that makes sense as a place to start, where we really can’t afford to do nothing, and where I think the solution will be almost as clear as the problem. But I’m under no illusion that there’s any chance of reaching an optimal regulatory environment with AI anytime soon. The goal shouldn’t be to find what’s optimal, the goal should be to literally not fail to do anything. And that’s definitely the most likely course—the most likely course is that we effectively do nothing. We should try really hard to avoid that.

The bill you’ve already introduced is supposed to prevent China from remotely accessing American technology to develop its own generative AI systems. How did that loophole end up existing in the first place and how does your bill help close it?

I can’t get into that specifically, because I don’t want to alert other potential bad actors to an opportunity that may exist to circumvent some controls. But what I’ll say is that you’re spot on in your summary, that there was a loophole for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to remotely access American technology online and to continue developing their AI tools and models. The purpose of the bill is to close that loophole and stop the CCP from using American technology to accelerate their own AI. That’s it.

Since you’re on the House Armed Services Committee, what are the most important things you communicate to constituents about what the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) is and what it does? And what do you consider its most important provisions as it heads to conference later this year?

I’m new to this, so my first two big impressions of the process were one, just how truly gigantic this bill really is, and two, how clearly designed it is to help us compete against China’s growing military abilities in several different domains. In the buildup to the NDAA, most of the hearings that we had were related in some way to China’s progress across different domains. Some of those hearings didn’t tell me anything I didn't already know, but some of them were fairly striking. Chair Mike Rogers was good at keeping us all headed in one direction, all the way to the last day, where we had to pass the bill out of committee—a marathon, 10-hour day. He was very good at keeping out most of the culture war stuff that the far right tried to pull in, and we were hoping that Speaker Kevin McCarthy would be able to exercise the same control when it got to the House floor. For some reason that just didn’t happen. It completely fell apart.

Are there any particular examples of things in those lead-up hearings that were striking to you in terms of competing with China?

China is aggressively growing its navy. One reason they can do that is because they co-locate their civilian and naval construction facilities. So because the government is calling all the shots, the CCP will say, “Okay, we’re going to build five tankers through this facility, and then we’re going to build a battleship with the same workers, the same material, the same supply lines, the same logistics.” And what we do is separate all that stuff out. We’re not building tankers at the same places we’re building battleships. Everything for our navy is to spec—which gets us a certain level of quality, but we pay an enormous price when it comes to efficiency.

Can we make gains in efficiency without sacrificing quality?

I don’t know. I do know that at a minimum, when the Navy says they’re no longer interested in continuing production for certain ships, we should probably take that seriously and cut our losses there. When the Navy says, “Here’s several billion dollars we don’t want to spend,” we should say, “Okay.”

There’s been speculation about your district being changed during redistricting in North Carolina, but you’ve been an anti-gerrymandering guy for a while before that. What’s next for potential reforms to redistricting at either the federal or state level? And since you’ve been a member of Congress, are there other electoral reforms you’ve learned about that appeal to you?

I guess we’ll just start with gerrymandering. I don’t know exactly what to expect in North Carolina, but I’m sure it’s going to be very bad. The state legislature has an enormous amount of power to redraw these maps. I think that power will be largely unchecked, and I think they will use it to maximum self-advantage. I have no particular insight or control over that situation.

The first bill I ever filed in the state legislature was to end gerrymandering. They sent it to the Ways and Means Committee—which in Washington is a very powerful committee, and in Raleigh is a committee that hasn’t met in 20 years. It’s the joke committee. If your bill gets sent there, that’s the graveyard. I filed it, I think, every term and never even got a hearing. So we have come much closer in the U.S. House to taking action against gerrymandering than we ever have in the North Carolina State House. And I plan on supporting that effort again, although I’m under no illusions that Speaker McCarthy would never allow that to come to a vote.

Are there any questions that you wish you were asked more by the press or by constituents?

In general, the national-level press is really interested in conflict. If I don’t have anything critical to say about another member, then you’re probably not going to get much attention from them. That’s been my experience so far. That’s not earth-shattering news to anyone who’s going to read this newsletter, but I’ve witnessed that several times firsthand.

A lot of bipartisan efforts receive minimal coverage, because in general the national press does not report on planes that land. I understand they have their own financial incentives for that. But given those financial incentives, it’s all the more important for people in my shoes to be able to communicate directly with their constituents. Because what my constituents hear is constant political warfare. So if you are in my shoes, and you just want to inform your constituents in a way that’s accurate and faithful to the actual experience, you really have to find a way to do that directly.

Of Note

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.