Amid all the debates over the Supreme Court’s year-end decisions, we should take a step back to recognize that the court’s term was a turning point—the end of one era and the still-early moments of another.

The affirmative action cases reflect the end of one era. Applying constitutional textualism, the court resolved one of the central constitutional debates of the last 40 years: the use of race in university admissions. Like last year’s Dobbs decision renouncing the Roe v. Wade precedent, the Students for Fair Admissions cases culminated one of the conservative legal movement’s formative issues.

Other cases exemplify the next era. From student loan cancellation to immigration, the court grappled with issues that are increasingly important in new chapters of constitutional litigation: the power of presidents to make sweeping new legal changes, the power of states to litigate against them, and more.

Along those lines, and beginning with the newer questions, here are four key themes from the court’s major cases.

The once and future chief.

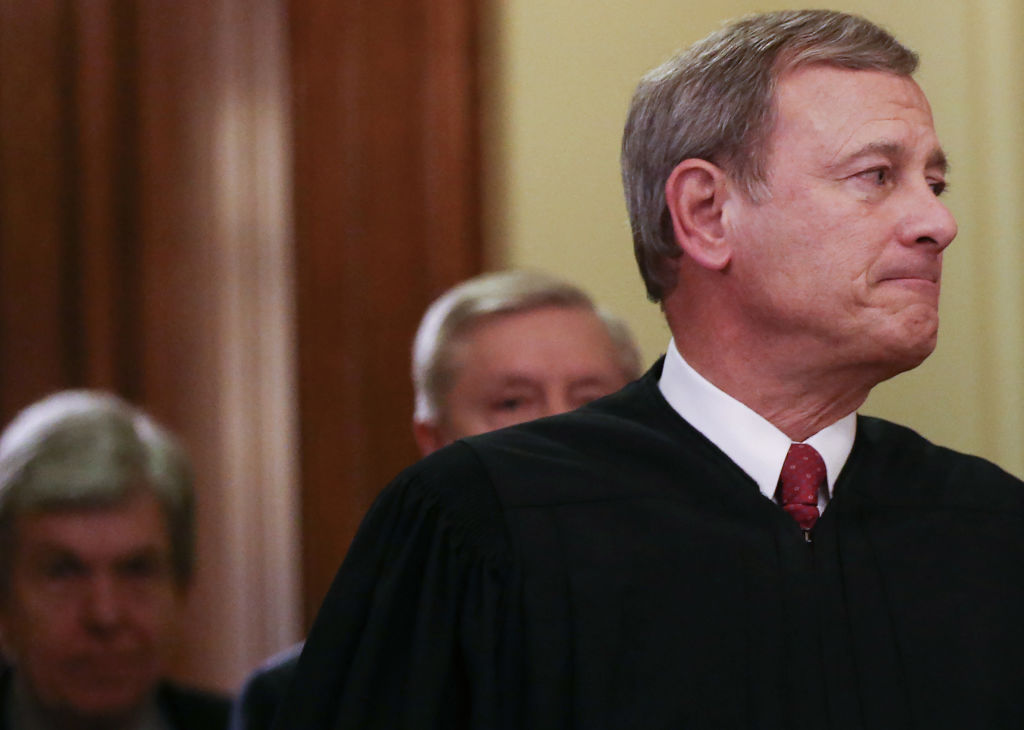

The best reason to hesitate before imposing narratives on the court is simply to recall narratives from a year ago. Many thought that Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health was not just the end of Roe v. Wade but also the end of the “Roberts” Court. The justices split sharply on the case’s merits, but eight of them seemed united in their disregard for the chief justice. The five-justice majority affirmed Louisiana’s abortion regulation and overturned Roe; three dissenters would have ruled for Roe and against the state legislature; only Chief Justice John Roberts wanted to affirm the state’s law and sidestep Roe debate altogether. Some of the court’s keenest observers declared that Roberts had “lost” the court.

But that narrative was wrong from the start. Roberts was in the majority more than any other justice besides Justice Brett Kavanaugh, with whom he tied, in 2021-22. Roberts also wrote more 6-3 and 5-4 majority opinions than anyone. With the court poised to hear major cases about affirmative action and the administrative state, 2022–2023 seemed destined to keep Roberts front and center.

And that is how the year played out. The chief justice was in the majority for 95 percent of this year’s decisions, barely edged out by Kavanaugh’s 96 percent. He assigned himself the court’s majority opinions in Students for Fair Admissions (affirmative action), Biden v. Nebraska (student loans), and Moore v. Harper (state legislatures and redistricting).

One important nuance in Roberts’ particular approach is his willingness to announce a broad rule defending the Constitution’s separation of powers, yet immediately adding caveats to prevent the rule from being taken too far.

In Moore v. Harper, the court held that state legislatures’ power (under the U.S. Constitution) to draw congressional districts is not immune to state courts’ ordinary power of judicial review (under state constitutions). Yet Roberts’ majority opinion included a crucial caveat: Just as state legislatures’ constitutional power is not unlimited, “state courts do not have free rein” either. The Supreme Court and lower federal courts will need to ensure that state courts do not change state law under the guise of “interpreting” the law, especially in elections with federal consequences: “State courts may not transgress the ordinary bounds of judicial review such that they arrogate to themselves the power vested in state legislatures to regulate federal elections.”

Many who cheered the court’s overall ruling against state legislatures bemoaned the court’s warning against state courts. “[T]he court offers no guidance, no standard at all, for lower courts to know when a state court has gone too far … no concrete understanding nor any example of what that means,” wrote law professor Rick Pildes. The professor is right: The court’s warning of state judicial overreach will spur election lawsuits in federal courts. The court’s refusal to accept state legislative omnipotence will not open the door to state judicial omnipotence—and the federal courts will inevitably be responsible for policing both.

But it has gone largely unnoticed that Roberts has done this before, in another important separation-of-powers case. In Trump v. Mazars (2020), the court rejected President Trump’s sweeping assertion of executive privilege against congressional subpoenas. But Roberts’ majority opinion in Mazars added a key caveat: Congressional subpoenas are enforceable only insofar as they advance “a legitimate task of Congress,” a “valid legislative purpose” concerning “a subject on which legislation ‘could be had.’” In other words, the court’s ruling against presidential privilege was more limited than the president’s critics would have preferred.

In these two decisions, the chief justice shows a distinctive approach to constitutional separation of powers, particularly in newly salient fights over how to allocate government power. Roberts seems keen to reassert judicial lines separating the branches of government while also recognizing that some lines cannot be drawn with perfect clarity. In that sense, this practical approach calls to mind James Madison’s warning, in Federalist 37: “Experience has instructed us that no skill in the science of government has yet been able to discriminate and define, with sufficient certainty, its three great provinces the legislative, executive, and judiciary; or even the privileges and powers of the different legislative branches.” Roberts seems comfortable announcing broad separation-of-powers principles, even while allowing that more specific lines may need to be drawn in future cases, by the courts, with an eye to specific facts.

The court may take this approach again next fall, in a case challenging the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s power to fund itself from the Federal Reserve independent of Congress. The CFPB’s defenders assert that the court cannot reject the CFPB’s perpetual purse without automatically striking down other agencies’ sources of non-congressional funding as well. But if Roberts approaches the case as he did in Moore and Mazars, he might well be comfortable writing a majority that strikes down the CFPB’s extreme example while saving more specific line-drawing for more difficult cases.

States and the administrative state.

Fifteen years ago, leading progressive legal scholar Gillian E. Metzger observed that “administrative law may be becoming the home of a new federalism.” She was absolutely right. The administrative state increasingly encroaches on states’ own authority, and administration-centric government makes anti-agency lawsuits inevitable.

This trend was energized by the Supreme Court’s decision in Massachusetts v. EPA (2007), approving a blue-state coalition’s lawsuit to force the Bush administration’s EPA to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. Crucially, the court held that the states themselves had legal “standing” to bring the lawsuit, and noted that states’ claims of standing to sue federal agencies deserve “special solicitude” from the courts.

The court’s encouragement of state litigants—over the vocal dissent of justices Scalia, Thomas, Roberts, and Alito—ushered in a new era of state litigation, with red- and blue-state AGs suing presidents of the other party and intervening to defend presidents of their own.

State-led litigation is now a central feature of modern constitutional and regulatory litigation—and, accordingly, so are fights over state standing. The court’s pair of year-end decisions in Biden v. Nebraska and U.S. v. Texas may prove particularly significant.

In Nebraska, the court held that Missouri had standing to challenge the Biden administration’s student-debt cancellation. But in Texas, the court held that Texas and Louisiana lacked standing to challenge the Biden administration’s guidelines for enforcing immigration laws.

The distinctions between these cases are crucial. For Nebraska, the court was convinced that the Biden administration’s policy would financially harm Missouri's state-chartered nonprofit corporation for servicing student loans, and that this was an injury to the state itself, because the nonprofit was the state’s special “instrumentality” for serving an “essential public function.” For Texas, by contrast, the court saw the state plaintiffs as effectively trying to micromanage the federal executive’s own enforcement discretion: Even if the states suffered financial harms from the Biden administration’s approach to immigration enforcement, the court would not allow the states to use litigation to second-guess the federal administration’s use of enforcement discretion in choosing whom to prosecute.

The Nebraska ruling on student loans may be more politically salient, but the Texas ruling on state standing may have farther-reaching consequences. As Gorsuch and Alito both noted in their separate opinions, the court’s skepticism of state standing seems to roll back Massachusetts v. EPA’s “special solicitude” for state plaintiffs. States will still have standing to challenge agency actions—but when presidents make policy through nominal assertions of “enforcement discretion,” state litigants may have to work harder to convince the court of their standing to sue.

The Texas decision also reflects its author’s long-stated sense of the role of the judicial and executive power in constitutional government. Kavanaugh, who penned the majority opinion, is hardly sympathetic to the modern administrative state. But he is also wary of judicial micromanagement of the executive branch, and the potential for lawsuits to drain energy from the executive. “The judicially created obstacle course can hinder Executive Branch agencies from rapidly and effectively responding to changing or emerging issues within their authority,” he wrote as a D.C. Circuit judge in 2008. “The trend has not been good as a jurisprudential matter, and it continues to have significant practical consequences for the operation of the Federal Government and those affected by federal regulation and deregulation.”

The modern doctrine of standing was meant to limit judicial encroachment on executive discretion, as emphasized over the years by Scalia and by Roberts (who joined Kavanaugh’s Texas opinion), among others. The Texas decision will not end state litigation against federal administrations—the growth of such litigation will continue to mirror the growth of administrative power. But it will make state litigants’ work more difficult.

Finally, the student loan case will prove important in the years to come for one more reason. In ruling that the Biden administration’s ambitious and unprecedented program was unlawful, the court once again invoked “the major questions doctrine”—a general rule of being skeptical, not deferential, to agencies’ self-aggrandizing interpretations of statutes on the most significant policy questions of our day. Several justices have explained the doctrine as a substantive defense of the Constitution’s separation of powers. But in this case, Justice Amy Coney Barrett wrote separately to offer an entirely different understanding of the doctrine.

Conservative justices have for years explained the major questions doctrine as a principle for protecting the Constitution’s separation of powers. Their opinions attracted applause from conservatives but criticism from others (especially Justice Kagan) who denigrated the doctrine as the justices’ own political value judgment, not as a genuine tool for interpreting a text’s original meaning. In Biden v. Nebraska, Barrett offered an entirely different account of the major questions doctrine, arguing that it is simply a tool for understanding the meaning of words by better understanding their “context”. To her, the major questions doctrine is “a tool for discerning—not departing from—the text’s most natural interpretation.”

Her opinion conceded that Kagan’s characterization of the major questions doctrine as anti-textualist had real bite. Barrett’s own account is scholarly and careful, reminiscent of her work as a legal scholar. She joined her colleagues’ major questions doctrine analyses in previous cases on EPA climate regulations or OSHA vaccine mandates, but this new opinion offers a very different account of the doctrine. Interestingly, none of her colleagues joined this new opinion. Perhaps the theoretical differences between Barrett and her colleagues will make little difference in actual case outcomes—but it could. What had been a two-sided debate between conservative and progressive justices is now a much richer and more nuanced debate between three sets of justices, and it will spur thoughtful writings in turn from lower-court judges and scholars.

The dissenters.

The progressive justices are also grappling with their own role in the court, and in constitutional politics more broadly—just as the early originalist justices did a generation ago.

When Scalia found himself often dissenting from the court’s decisions, he explained that he wrote colorfully and pointedly for a reason. “I think sharpness is sometimes needed to demonstrate how much of a departure I believe the thing is,” he explained to a reporter. “Especially in my dissents. Who do you think I write my dissents for?” He was writing for the future—for law students. “And they will read dissents that are breezy and have some thrust to them. That’s who I write for.”

His critics, of course, saw it differently. “One rough measure of how any Supreme Court term is going is to track the decibel level of Justice Antonin Scalia’s dissenting opinions,” the New York Times’s Linda Greenhouse chortled in 2011. When a particular decision “enraged” Scalia, his dissent “complained” or “lashed out” at the majority. “With the result he desired having slipped from his grasp,” Greenhouse added, the “furious” justice would drop rhetorical bombs on his colleagues. Such a heated dissent, she concluded, was simply “an exercise in self-indulgence that could serve only to undermine the court’s own legitimacy.”

In hindsight, however, it’s clear that Greenhouse’s own self-indulgence was mistaken. Dissenting justices can move broader constitutional audiences, in the short and long run alike. Scalia’s dissents inspired the generational change in constitutional jurisprudence that is now bearing fruit in the Supreme Court and lower courts.

Are the court’s current dissenters thinking in similar generational terms? Some of their year-end dissents clearly indicate that they are looking for a much broader political audience. Greenhouse’s colleagues at the Times highlighted Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s dissent in the race-based admissions cases: full of “scathing language,” the justice’s dissent “ended on a defiant note, writing that despite the court’s actions, ‘society’s progress toward equality cannot be permanently halted.’” (And in case you are wondering, Greenhouse applauded Sotomayor’s dissent.)

Slate’s Dahlia Lithwick parsed the progressive justices’ prominent dissents and concluded that each justice’s rhetoric reflects a distinct judicial aim. Sotomayor’s dissents, Lithwick writes, exemplify her role as “the People’s Justice,” the “the voice for the kinds of people who are not visible to the justices who now write the majority opinions.” Elena Kagan, meanwhile, “thinks about the court in institutional ways that transcend any single case, and her dissent in Biden v. Nebraska, the court’s big student debt relief case, highlighted the structural role she’s assigned to herself.” And Ketanji Brown Jackson “has chosen to carve out her own path in terms of taking seriously the project of originalism, history, and textualism, and has set herself the task of becoming a meaningful voice for progressive originalism.”

Lithwick’s characterizations are sweeping, though not implausible. But each of those three kinds of judicial rhetoric—cultural, institutional, and methodological—was found in Scalia’s dissents. That was the point: Scalia’s dissents were powerful precisely because they combined all three kinds of arguments with a style that captured the attention of law students and citizens alike.

The question is whether any of the three dissenters will imitate Scalia’s comprehensive approach over the course of a decade or more. If anything, Kagan deserves more credit that Lithwick gives her, because Kagan’s dissents seem modeled after Scalia’s broad and deep approach. Indeed, Kagan has often expressed affection and admiration of Scalia. And like Scalia, Kagan’s roots are in both academia and political government, making her particularly well suited to write in multiple registers.

Will she continue in that path—and, if so, will she succeed as Scalia did? Will the others?

Race-based university admissions—the end and the beginning.

As I noted at the outset, the Students for Fair Admissions cases were the end of a generational era. Alongside abortion and federalism, racial distinctions in the law were one of the formative issues of the conservative legal movement. The court’s seminal decision on the issue, 1978’s Bakke case approving affirmative action, occurred just as the conservative legal movement itself was coming into existence. Many cases followed, especially the early-2000s Grutter decision that reendorsed affirmative action, with the “expect[ation] that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.” Four decades of debate and litigation, culminating with the Harvard and North Carolina cases, centered around fundamental debates over how to interpret the 14th Amendment’s words, and how to understand the history and principles that those words embodied.

Litigation over the 14th Amendment will continue, of course, though it may turn out to be mainly over the facts of universities’ practices, not the laws that govern them. But this, too, is reminiscent of Dobbs, a decision that anticipated future cases would raise practical questions, but announced the broad principle nonetheless.

Finally, the university cases are also the culmination of Justice Thomas’ work and thought. No matter how much longer he serves on the court, his Students for Fair Admissions concurrence may be the opinion for which he is best remembered.

The 58-page opinion collects and reiterates an understanding of the law—and of the nation—that Thomas embraced and emphasized even before his appointment to the court. From 1987 to 1989, as chairman of the Equal Employment and Opportunity Commission, he wrote three essays on the Declaration of Independence, the 14th Amendment, and the Civil Rights Act. He argued that the Constitution must be understood as embodying the Declaration’s recognition of every man’s liberty and equality. He celebrated Justice Harlan’s dissent from Plessy v. Ferguson’s separate-but-equal infamy as “one of our best examples of natural rights or higher law jurisprudence.” And in a Cato Institute book assessing President Reagan’s administration, he criticized racial affirmative action as not just unlawful but corrosive and counterproductive.

These stunning essays raised themes that he would reiterate throughout his time on the Supreme Court. Decades later, his opinion in Students for Fair Admissions is his valedictory.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.