A major political and power shift is underway in Washington—beyond a changing of the guard at the White House and on Capitol Hill.

First, the incoming Republican majority in the United States Senate is signaling a willingness to abdicate influence over legislation and administration appointments to the White House and President-elect Donald Trump. Inside the GOP, meanwhile, Trump’s reelection after one term out of office has cemented the ascension of the populists, who have leapfrogged traditional conservatives and now command the party’s governing coalition.

“I think it’s gonna be a long time, if ever, before we see the Senate as an epicenter of power again,” a Republican operative and former Senate aide said, requesting anonymity to speak candidly. More than a half-dozen Republican insiders who have spent decades working in Washington echoed that sentiment to The Dispatch, saying it appears Senate Republicans are transforming from a check on executive power to White House facilitator.

The evolution was most apparent this week when the three Senate Republicans who vied to succeed Kentucky’s Mitch McConnell as majority leader said they were open to bowing to president-elect’s demands for recess appointments, abandoning years of bipartisan precedent. Under the Constitution, a president can fill administration posts that otherwise require Senate confirmation if the chamber is in recess for at least 10 days, which both parties have prevented by holding quick, “pro forma” sessions roughly every 72 hours. So, with an expected 53-seat GOP majority, pushing through recess appointments would appear to be about sidestepping Republican, not Democratic, opposition to Trump’s picks.

“I’ll support anybody President Trump nominates,” Sen.-elect Bernie Moreno of Ohio told Semafor. “There should be massive deference given to him.” Added Sen. Tommy Tuberville of Alabama, in an interview on Fox Business Network: “President Trump and [Vice President-elect] J.D. Vance are going to be running the Senate.”

Fresh Trump nominations may put those statements to the test.

On Wednesday, Trump nominated Tulsi Gabbard for director of national intelligence and Rep. Matt Gaetz of Florida for attorney general (he resigned his House seat hours later). Gabbard, a former Democrat and former Hawaii congresswoman, has over the years expressed a dim view of American global leadership and aligned herself with U.S. adversaries. Gaetz, the subject of a House ethics investigation, is a polarizing Trump loyalist with a thin legal résumé who on the House Judiciary Committee has prioritized probing the various legal investigations into the former president.

Then there’s Robert F. Kennedy Jr. On Thursday, Trump announced that he was nominating the anti-vaccine activist for secretary of Health and Human Services.

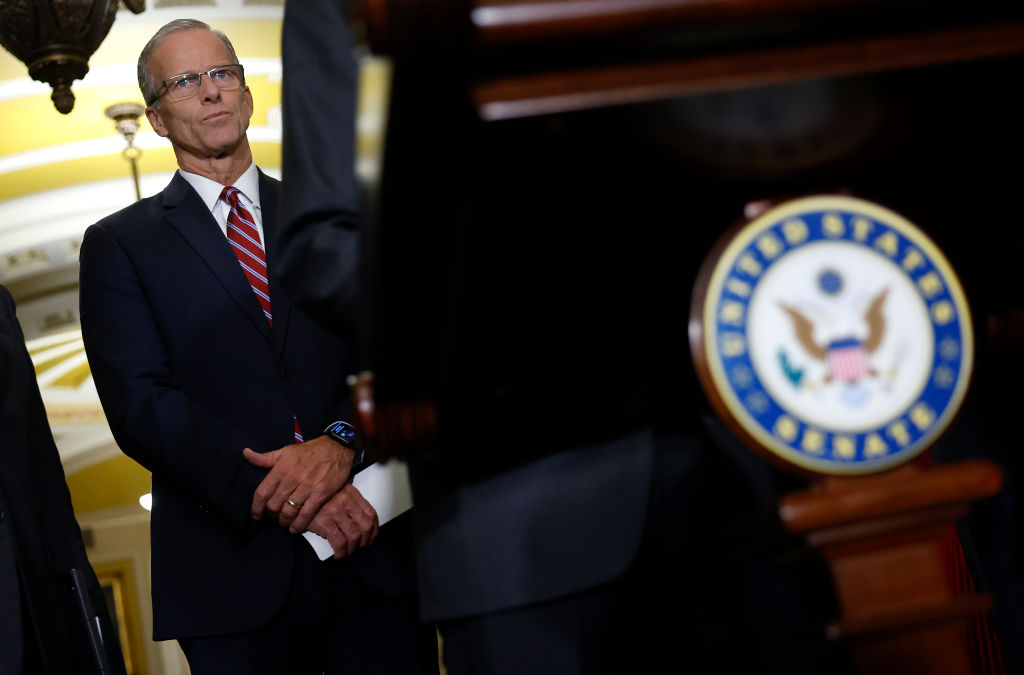

Under normal circumstances, many Senate Republicans might oppose these nominees. And these are likely not the last of Trump’s potentially controversial appointments. All eyes are now on the confirmation process and new Senate Majority Leader John Thune of South Dakota, who on Wednesday bested Sens. John Cornyn of Texas and Rick Scott of Florida in a close, secret-ballot leadership election.

But the shift in political power dynamics inside the Republican Party goes deeper than Senate leadership.

For decades, populists and traditional conservatives existed together as members of the GOP electoral and governing coalition. But for four-plus decades, beginning with the election of President Ronald Reagan, the traditional conservatives held sway, with populists playing the role of junior partner. That translated into a GOP that promoted a smaller, less active federal government; free enterprise and free trade; American global leadership; and opposition to abortion rights.

But now the Republican Party seems to be more interested in pushing big-government style industrial policy; opposing significant spending cuts to bring the federal debt and deficit under control; questioning American leadership abroad; supporting large-scale tariffs on imported goods; and in the aftermath of the overturning of Roe v. Wade, opposing national restrictions on abortion.

Any possibility that Reaganites inside the GOP might be resurgent was quashed last week when Trump defeated Vice President Kamala Harris. That seemed especially true because this time around, Trump’s running mate was Vance, the populist senator from Ohio—unlike in 2020 when it was Indiana Gov. Mike Pence, a Reagan-era, traditional conservative.

“The party of George W. Bush kind of has their nose pressing against the glass, looking in,” said a Republican lobbyist, whose tenure in Washington dates back to the 1990s. A Republican strategist who has been in town just as long explained the demotion of the Reaganites, and elevation of the populists, this way: “Entitlement reform is over, no matter what Paul Ryan wants.”

No Reagan Republican seems more acutely aware of how things have changed than Pence. His falling out with Trump was not ideological, but related to the former president’s handling of his 2020 loss to Joe Biden. But Pence now acknowledges that the traditional conservative faction of the party is effectively playing second fiddle to the populists in Trump’s coalition.

During an appearance Tuesday at the The Dispatch Summit 2024, the former vice president said the policies that first drew him to the GOP more than 40 years ago and, in his view, largely dominated Trump’s agenda in the first term, have been undercut or replaced altogether by a “populism unmoored from conservative principles.” Specifically, he said, that includes abandoning American allies overseas; marginalizing the party’s once staunch opposition to abortion; and deprioritizing policies that address the nation’s historic deficit and debt load.

“Conservatives need to understand that we are, in a very real sense, part of a broader coalition and now we need to do our job. We need to make the case for principled conservatism,” Pence said in an extensive interview, his first since the November 5 election. “At the end of the day, I think it’s incumbent on us to take up the mantle and make the case and ensure that those principles of conservatism win in the Republican Party.”

After Trump’s first victory in 2016 and throughout the 45th president’s first term, Senate Republicans worked assiduously to avoid public spats with the seemingly unlikely commander in chief, fearing an angry Twitter post that might spark opposition from grassroots supporters back home. Still, Republicans in the Senate were plenty willing to oppose confirmation of Trump administration appointees, and push back on White House policy, when compelled. That approach was in keeping with the flukey nature of Trump’s first win: He lost the popular vote to Democrat Hillary Clinton and won 306 Electoral College votes thanks to slim advantages in four swing states—Florida, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

This time around, Trump won the popular vote, swept Harris in all seven swing states, saw his vote share increase in both blue and red states, and performed better with Hispanics and other non-white voters than any Republican in a generation. To Pence’s point, that outcome has changed the nature of the GOP coalition to include more voters who are not traditional conservatives but are looking for Trump to address inflation and public safety, particularly as it relates to security along the U.S.-Mexico border.

As such, some Republican operatives in Washington believe the populist hold over the Republican Party is less durable than it might appear.

These skeptics argue that Trump is a unique figure capable of luring voters unlikely to back a Republican viewed as a normal politician—populist or not—and was buoyed by widespread concerns among several voting blocs about the economy and border security. These populist voters are still in play in future elections, open to supporting Republicans running as traditional conservatives, not to mention Democrats of various stripes.

“The coalition is going to fray,” one Republican operative predicted, explaining the GOP is currently made up of so many factions—on the right but not only on the right—that it will be nearly impossible to hold together under the strain of governing.

Additionally, some veteran D.C. operatives say too much is being made of the openness on the part of Senate Republicans to defer to Trump on administration appointments and sideline their constitutional power to shape presidential picks via advice and consent.

Some of what the GOP candidates for Senate majority leader were signaling in regard to recess appointments was about political expediency: They wanted to avoid opposition from Trump and ensure they were positioned to win. Others say the threat of recess appointments was a shot across the bow at Senate Democrats, who could use procedural tactics to delay confirmations. (It should be noted that adjourning the Senate to initiate a recess in and of itself requires 60 votes, and therefore Democratic support.)

Then there is the fear of the tweet, so to speak. While rank-and-file Senate Republicans may be caught up in the euphoria of their party’s clean sweep in last Tuesday’s elections, it’s also quite possible they’re downplaying concerns about Trump’s demands to avoid a confrontation with the incoming president.

“That may cool some once they get past leadership elections,” a party strategist said. “Everyone just doesn’t want to be the focus of a Truth Social post right now.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.