Democrats are feeling giddy over President Joe Biden’s decision to drop out of the 2024 presidential race and pave the way for Vice President Kamala Harris to run in his place. But before Biden’s disastrous June 27 debate performance, many considered Harris to be an even weaker candidate than the president—a feeling that he and his top advisers couldn’t shake for weeks after the debate debacle.

That concern was partly due to Harris’ habit of spouting Veep-esque pablum in interviews and partly due to the fact that she had staked out a policy record as a 2020 Democratic presidential candidate and California politician that was far to the left of “Scranton Joe,” who had squeaked to victory in 2020 by less than 1 percentage point in Wisconsin, Georgia, and Arizona.

The vice president now faces two daunting tasks in her 100-day sprint to November 5: sufficiently separating herself from an unpopular incumbent and allaying concerns among swing voters about her progressive record. Here’s a overview of Harris’ record on seven domestic policy issues that could shape the 2024 race:

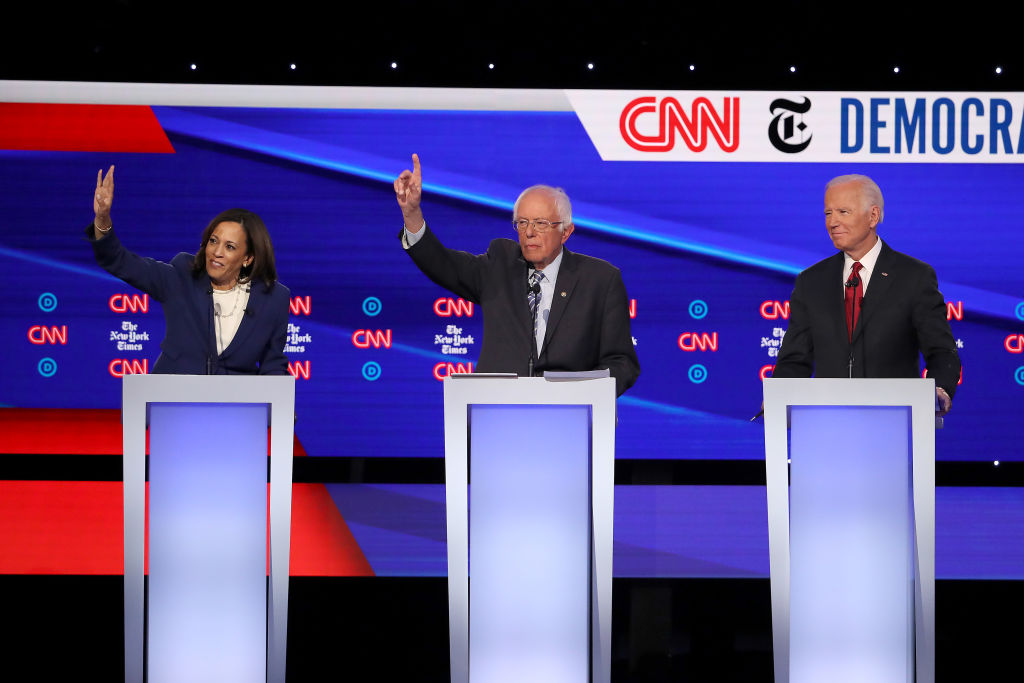

Medicare for All

One of the key differences between Biden and most of his Democratic primary opponents in 2020 was the issue of “Medicare for All.” While Biden opposed a single-payer health care plan, Harris was an original co-sponsor of Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders’ Medicare for All legislation. In January 2019, CNN’s Jake Tapper asked Harris in a town hall forum: “I believe it will totally eliminate private insurance. So for people out there who like their insurance, they don’t get to keep it?” Harris replied: “Let’s eliminate all of that. Let’s move on.” Harris later insisted she only supported getting rid of “bureaucracy” and “waste” and claimed the Sanders bill didn’t eliminate private insurance because it allowed supplemental plans. But Sanders’ bill provided for supplemental insurance only for services not typically covered by traditional insurance, such as cosmetic surgery. In July 2019, Harris released her own Medicare for All proposal that promised to maintain existing insurance plans for a 10-year transition period.

Energy and Climate

In 2019, Harris co-sponsored Green New Deal legislation introduced by Massachusetts Sen. Ed Markey and New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. During her presidential campaign, which ended in December 2019 amid bleak poll numbers, Harris introduced a climate plan that dedicated $10 trillion to implementing the program. Harris said the funds would make 100 percent of cars carbon-neutral by 2035 and create a carbon-neutral economy by 2045. “As president of the United States, I am prepared to get rid of the filibuster to pass a Green New Deal,” she said at the time. Harris also said in a CNN town hall meeting that year: “There’s no question I’m in favor of banning fracking.” CNN reported that she “walked back that support” for banning fracking when she became Biden’s running mate.

The Supreme Court

While Biden opposed increasing the number of Supreme Court justices during the 2020 presidential campaign, Harris said she was open to the proposal. Politico reported in March 2019 that Harris “would not rule out expanding the Supreme Court if elected president, showcasing a new level of interest in the Democratic field on an issue that has until recently remained on the fringes of debate.”

“We are on the verge of a crisis of confidence in the Supreme Court,” Harris told Politico. “We have to take this challenge head on, and everything is on the table to do that.”

Gun Control

In 2019, Harris claimed that as president she would issue an executive order to ban so-called assault weapons, but in a September 2019 debate, Biden said “there’s no constitutional authority to issue that executive order.”

“Hey, Joe, instead of saying, no, we can’t, let’s say yes, we can,” Harris said. Replied Biden: “Let’s be constitutional. We’ve got a Constitution.”

As a presidential candidate, Harris didn’t just support a ban on new sales of assault weapons but favored a mandatory buyback program to confiscate assault weapons owned by Americans.

Harris told reporters in 2019 that she owns a handgun: “I own a gun for probably the reason that a lot of people do—for personal safety. I was a career prosecutor.” As San Francisco district attorney, Harris filed an amicus brief urging the Supreme Court not to find a broad right to gun ownership in the 2008 District of Columbia v. Heller case.

Abortion

The differences between Biden and Harris on abortion generally have more to do with rhetoric than substance. While Biden once opposed Roe v. Wade, voted in favor of the partial-birth abortion ban, and supported the Hyde amendment prohibiting federal funding of elective abortion, he reversed himself on Roe in the 1980s and on the Hyde amendment in 2019. Since the 2022 Dobbs decision that overturned Roe, progressives have been frustrated that Biden hasn’t spoken more about abortion but pleased that Harris has been front and center in holding campaign rallies on the issue.

In March, she became the first sitting vice president to visit an abortion clinic when she toured a Minnesota Planned Parenthood facility that advertised performing elective abortions up to nearly 24 weeks of pregnancy and making referrals for abortions later than that. As a senator, Harris interrogated a judicial nominee over his membership in the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic charity and fraternal group with 2 million members, because its leader opposed abortion.

On Face the Nation in September 2023, Harris said it was a “mischaracterization” for Republicans to say Democrats support abortion up until birth but would not give a specific answer when host Margaret Brennan asked: “What week of pregnancy should abortion access be cut off?"

In the Senate, Harris co-sponsored the Women’s Health Protection Act, legislation introduced before the Dobbs decision that would have created a sweeping national right to abortion, including a liberal mental-health exception after an unborn child could survive outside the womb. Every Democratic senator supported that bill in 2022, except for Joe Manchin of West Virginia, who opposed it on the grounds it would eliminate modest state level restrictions allowed under Roe v. Wade.

Harris is intent on making the abortion issue a central focus of the 2024 campaign, but it’s not clear how much it will help her. Since the Dobbs decision, advocates of a right to abortion have prevailed in every state where an abortion referendum was on the ballot, but Republican candidates who opposed abortion generally did not pay much of a price at the polls in the 2022 midterm elections.

Criminal Justice

In her first stump speeches since Biden dropped out of the race, Harris clearly aimed to also put her record as a prosecutor at the top of voters’ minds. At her rally in Milwaukee on Monday, Harris said that as a prosecutor she took on “predators who abused women, fraudsters who ripped off consumers, cheaters who broke the rules for their own gain. So hear me when I say I know Donald Trump’s type.”

During the 2020 Democratic primary, Harris was attacked from the left by her rivals for supporting jail time for parents of chronically truant children and prosecuting marijuana-related crimes.

But the Trump campaign has already signaled it intends to hit Harris for being soft on crime. As a San Francisco district attorney, Harris declined to seek the death penalty for a man convicted of murdering a police officer, even though Democratic California Sen. Dianne Feinstein explicitly called on Harris to do so. Harris’ handling of the case was a key issue in her 2010 state attorney general race that she won by less than a point, even as all other statewide Democratic candidates won by double digits. Since 2010, however, Gallup polling has found that support for the death penalty has significantly declined nationwide.

In 2020, Harris praised Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti’s proposal to cut $250 million earmarked for the police and redirect those funds to health care and jobs programs. That same year, she posted on Twitter a link to the bail fund for those arrested protesting the murder of George Floyd, encouraging donations. In a 2020 campaign memo, she also favored ending cash bail and mandatory-minimum sentences.

Immigration

While Harris and Democrats want to focus on abortion and her record as a prosecutor, Trump and Republicans want to zero in on Harris’ role in the Biden administration’s handling of immigration. The crisis at the U.S.-Mexico border badly hurt President Biden’s job approval ratings, and in the administration’s early days the vice president was tapped for a key role in addressing the problem.

Trump is campaigning against Harris as Biden’s “border czar,” but the Harris campaign says it is false to describe Harris’ role that way even though several media outlets described her as a “point person” or “czar” on immigration in 2021. The term “czar” is not an official title—it’s typically used to refer to an executive branch official tasked with overseeing a particular issue. For example, many media reports dubbed Vice President Mike Pence the “coronavirus czar” in February 2020. When Biden took office, Roberta Jacobson, former ambassador to Mexico, was widely described in the media as Biden’s “border czar,” and when she left that role in April 2021, the Biden administration indicated Harris would be taking over Jacobson’s key duties. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said in a statement that Jacobson had "launched our renewed efforts with the Northern Triangle nations of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras" and added:

President Biden has asked Vice President Kamala Harris to lead the Administration’s work on our efforts with Mexico and the Northern Triangle, a testament to the importance this administration places on improving conditions in the region. The Vice President is overseeing a whole-of-government approach supported by outstanding public servants across the interagency including Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas and Secretary of Health and Human Services Xavier Becerra, who were tasked by the President at the beginning of the administration to rebuild our immigration system.

On Wednesday, The Dispatch contacted both the White House and the Harris presidential campaign seeking clarity on Jacobson’s portfolio of issues. We also asked whether border czar Jacobson had a successor, and, if she didn’t, how her portfolio was divided up among administration officials. The White House and Harris campaign did not provide any answers.

Regardless of whether Harris’ work addressing the root causes of migration from Central American nations earned her the unofficial title of “border czar,” she will undoubtedly face questions about the fact that the flow of illegal immigrants into the U.S. reached record highs before the president's recent executive order.

Harris may also face questions about positions she staked out during the 2020 Democratic presidential primary. When asked in 2018 if she would abolish Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Harris said in an interview: “We need to probably think about starting from scratch.” In a 2019 Democratic presidential debate, both Harris and Biden indicated they supported making illegal entry into the United States a civil rather than criminal offense—a policy Vox described as “the most radical immigration idea in the 2020 primary.”

While it’s unclear which aspects of her record Harris seeks to emphasize, downplay, or abandon, how she handles these questions between now and when voters begin heading to the polls could very well determine the outcome of the election.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.