Forgive me, fiscal conservatives, for the pain I’m about to inflict on you. Watch through your (pudding) fingers if you must, but watch. Together the two ads below raise an essential question about the nature of the modern GOP.

In 2012, the party’s presidential ticket included Paul Ryan. In 2024, it will almost certainly feature a nominee who campaigned against reforming entitlements in the Republican primary. As a measure of how unserious the right has become about solving the country’s most challenging problems, that’s tough to beat.

Others have made that point, though. The thought I had when watching the ads is this:

What is the Trump revolution ultimately about?

To be a revolutionary Republican in good standing, a member of the populist movement that’s remade the GOP since 2016, what must one believe and prioritize?

“Judging from the ads, it seems like you need to oppose entitlement reform,” you might say, logically enough. But is it true? If Marjorie Taylor Greene came out for reforming Social and Security and Medicare gradually to make them sustainable for younger Americans while remaining committed to the MAGA cultural agenda in all particulars, would she be unelectable in her very red district in 2024?

Would Trump no longer take her calls? Would it affect her standing in the party at all?

The two ads are about entitlements only nominally. What they’re really about is defining counterrevolutionary behavior.

On Monday Sarah Longwell published a piece at The Bulwark picking up on something she’s heard from Republican voters in focus groups. “We’re never going back” to the pre-Trump GOP, they warn her when asked about figures like Nikki Haley and Mike Pence. What, specifically, they disliked about what Longwell calls the “Before Trump” era isn’t clear; nevertheless, panelists will reliably grumble about the “establishment” pedigree or unwillingness to “fight” of any politician who made their bones during that period.

Even working at the uppermost levels of Trump’s own administration, as Pence and Haley both did, apparently can’t wash off the “Before Trump” stink.

Longwell never uses the R-word but it’s plain as day that she’s describing a revolutionary mindset among Republican voters. The ancien régime was toppled in 2016; the revolution prevailed; revolutionary progress requires that members of that regime never again be trusted with power.

I wrote about that last month. It’s key to the coming death match between Trump and Ron DeSantis, I’m convinced. Which of them will be deemed the revolutionary candidate and which the counterrevolutionary by Republican primary voters?

For Trump and his fans, that’s easy. He is the revolution.

He led it to power in 2016. He can’t be counterrevolutionary any more than Fidel Castro could, which is why he and his supporters find DeSantis’ willingness to oppose him so galling. It’s not just a wound to Trump’s ego or a threat to his hold on power over the right, it’s an affront to his stature as leader of the revolution. Imagine John Adams or Alexander Hamilton challenging George Washington for the presidency.

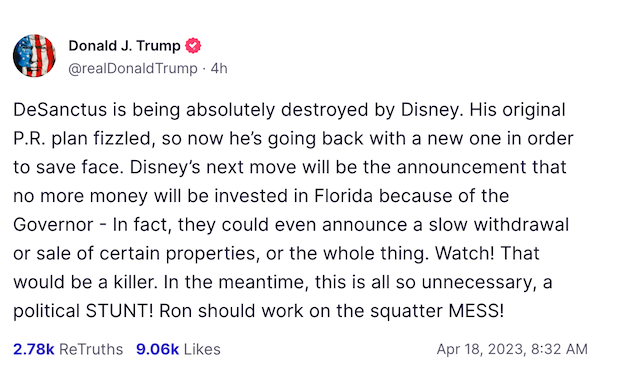

Entitlement reform is a potent issue. Trump’s “pudding fingers” ad is obviously designed to spook the more fiscally liberal working-class populists whom he brought into the party about his younger opponent. But its broader meaning has to do with revolutionary politics, reminding Republican voters that DeSantis was once part of the pre-Trump ancien régime and shared its ideological preferences. Choosing him as nominee would bring the revolution to an end.

Note how Longwell describes the criticism of DeSantis she’s begun to hear in Republican focus groups. It’s not specific to entitlements. It’s more attitudinal.

Voters I talked to recently say they’re “a little concerned” about DeSantis “because he’s still establishment,” and that “he seems like more of an open-borders, Paul Ryan kind of guy.” Others called him “more of a politician than Trump is” and said “he is very much one of those political, swampy guys.”

Words that stood out when we asked voters to describe DeSantis: “wishy-washy,” “a little shady,” and “not trustworthy.” One said, “I just don't have a good feeling in my gut about him.”

There’s nothing in there about Medicare or Social Security. It’s all variations on the theme that DeSantis is a closet counterrevolutionary. There is, after all, a reason that Trump’s critiques of him frequently invoke Paul Ryan and Jeb Bush. Ryan and Bush are supreme exemplars of the ancien régime; no modern Republican who would emulate them could truly be revolutionary, or so Trump would have populist voters believe.

How Trump might describe the agenda of his own political movement in 2023 is anyone’s guess. Presumably he’d say something about empowering “the forgotten man” (empowering him “very strongly,” I should say) by prioritizing working-class concerns like entitlements and border control over elite Republican hobby horses like, er, tax cuts. But with precious few exceptions, I don’t know that there’s any bedrock ideological content to it independent of the whims of the man himself. What, for instance, is the proper Trumpist revolutionary position on abortion at the moment?

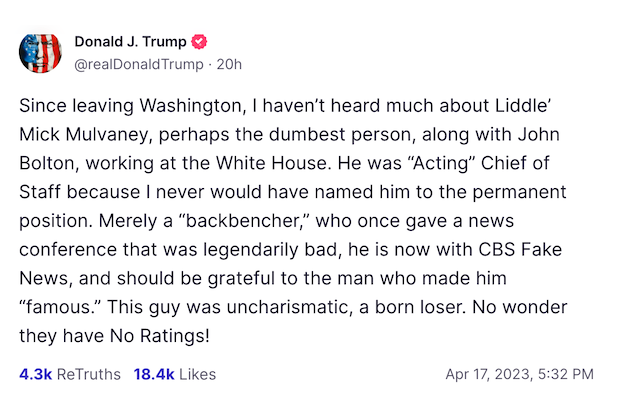

His movement has always concerned itself with ousting its political enemies from power more so than offering a detailed policy program and those enemies are chiefly among the American right. That’s why Trump is all but immune from criticism from his antagonists: When an ancien régime Republican like Mitch McConnell or a progressive Democrat like Alvin Bragg comes after him, it enhances his revolutionary credentials, irrespective of whether their complaints are valid. It’s a case of the “system” trying to take him down.

Here, for instance, is what Bragg’s indictment has done for him.

That’s what DeSantis is up against. How dare he try to topple the leader of the revolution at a moment when Democrats are also trying to topple him?

The governor has his own theory of what the Trump revolution is about, though.

To DeSantis and his supporters, Trumpism isn’t about Trump himself or about supplanting the Republican establishment. In fact, despite the rich opportunities for populist demagoguery available to him by attacking McConnell, Ryan, Bush, and other “Before Trump” villains, the governor rarely shoots inside his party’s tent.

His theory of the revolution is that it’s about prosecuting and winning the culture war against the common enemy, the American left, which explains why his base of support is a strange and possibly irreconcilable brew of populists and anti-Trump traditional conservatives. If the left worries you more than the right’s ancien régime does—and there are lots of Republicans across the spectrum for whom that’s true—you’re likely to find DeSantis a better fit for your politics than Trump.

The DeSantis ad at the top of this post drew snickers from critics for seeming to take offense that Donald Trump, of all people, might be mean to a fellow Republican. Being mean to Republicans has been Trump’s entire shtick since 2015, they scoffed. Indeed—but only “Before Trump” conservatives like Bush, McConnell, Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz, etc. Displaying contempt for them is perfectly proper revolutionary behavior. The point of DeSantis’ endless culture-war crusade over the last two years has been to (re)define himself as an “After Trump” conservative so unimpeachable in his own revolutionary fervor that even Trump can’t attack him without sounding … counterrevolutionary.

He’s doubling down on his increasingly weird vendetta against Disney. He’s siding with populists in their boycott of Anheuser-Busch. He’s trying to expand the death penalty in Florida to include crimes beyond murder. He’s pushing a tough new immigration bill that would punish anyone who aids an illegal immigrant. All of that comes on top of celebrated culture-war legislation like the “Stop WOKE Act” and the so-called “don’t say gay” law, keeping his state open during the pandemic amid pressure to lock down from the public-health bureaucracy, and plenty of pandering to right-wing anti-vaxxers on COVID vaccines.

DeSantis is leading a revolution in Florida against left-wing cultural preferences. For Trump to attack him in the middle of it—from the left, no less, about entitlements—invites populists to ask themselves who’s more committed to seeing the revolution triumph. The governor means to turn the question around on his opponent: How dare Trump try to topple the leader of the revolution at a moment when he’s trying to topple the Democrats?

That’s the point of his super PAC’s new ad. And if it’s not clear enough from the new ad, it should be clear enough from this one.

If—if—the Trump revolution is ultimately about advancing the right’s cultural agenda, not smashing the Republican ancien régime, DeSantis is the better revolutionary, no?

Would a true populist revolutionary side with Disney over the governor?

Would a true populist revolutionary have condoned lockdowns?

Would a true populist revolutionary complain privately about strict new abortion laws? Would he agree that Vladimir Putin is a “genocidal monster”? Would he urge people to get vaccinated?

Would his son, one of his most trusted advisers, be urging fellow revolutionaries to abandon their boycott of Anheuser-Busch because the company donates heavily to the Republican Party?

Would a true populist revolutionary have hired numerous “Before Trump” Republicans to staff his administration only to find himself disappointed in all of them?

If Trump is the revolution, and if empowering him at the expense of the Republican establishment is the highest political goal, then Ron DeSantis and anyone else who gets in his way are counterrevolutionary. Not coincidentally, a voter who subscribes to that view doesn’t much care about winning general elections. He prefers to roll the dice on unelectable uber-Trumpers like Doug Mastriano, to remind the GOP’s ancien régime who’s boss.

But if the revolution is about reversing left-wing cultural victories, then Trump himself is counterrevolutionary. He shares liberal cultural preferences to a greater degree than DeSantis does; he facilitated Democrats’ takeover of the federal government by alienating swing voters in 2018 and 2020; he continues to promote conspiracy theories and assorted other insanity that will render him even less electable in 2024; and he’s damaging the right’s most effective governor in the process. Electability is of utmost importance to a voter who subscribes to this view of the revolution.

How can a single party accommodate two revolutions that are increasingly at cross-purposes?

When you look at the Republican Party that way, it’s easy to see why it might struggle to galvanize a meaningful number of its voters in 2024.

If DeSantis is the nominee, some populists who see Trump as the revolution will be inconsolable. Most will turn out anyway in the general election to vote against Joe Biden, but there will be a faction that can’t support a Republican who got his start in politics in a “Before Trump” House caucus dominated by Paul Ryan. DeSantis’ nomination ended the revolution, they’ll conclude—and perhaps not without reason. Some of the governor’s well-heeled donors have reportedly begun pushing him toward more traditionally conservative positions on subjects like Ukraine. “My understanding is that the message was: ‘If we wanted a f—ing MAGA candidate, we would donate to Donald Trump,’” a source told Rolling Stone of their message to DeSantis.

President DeSantis might govern more like the ancien régime version of himself than the revolutionary version.

If Trump is the nominee, most of DeSantis’ supporters will turn out for him, believing that a highly flawed culture warrior is still preferable to Joe Biden. But here again, a faction that spent the primary watching Trump attack DeSantis from the left on entitlements, on foreign policy, and possibly on abortion—amid a slew of nastier, viscerally offensive personal attacks—will conclude that there’s nothing left worth supporting about this party. Given a choice between a substantive policy revolution led by DeSantis and a cult of personality led by Trump, most Republican voters chose the cult. For some conservatives, it’ll be the last straw.

As a wise man said, Jacobins always end up guillotining each other.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.