Dear Capitolisters,

Recent events surrounding troubled U.S. electric vehicle company Lordstown Motors have me thinking about federal efforts to “save” American communities, especially those once reliant on manufacturing. Lordstown Motors, as you may recall, was named after the town in Ohio in which it resides—a town that’s part of the often-covered Youngstown area and became the center of a brief political firestorm when GM announced it was closing a plant there (the last in a long line of Youngstown plant closures), much to President Trump’s chagrin. Since then, the electric vehicle company has had some rather difficult times, first reporting that it had a bunch of orders for its electric trucks, only to walk that back, only to claim that, no, it really did have the orders, right before walking that back too—and losing several top executives (and gaining an insider trading problem?) in the process. And oh by the way, they also might not have enough cash to continue as a going concern through the end of the year.

But, as entertaining as these developments are, I think they hit on a broader point about the limits of federal intervention in reviving struggling localities in the United States—and how those efforts might even make things worse.

But First, a Note on ‘Mill Town’ Nostalgia

Before we dig in, however, it’s good to recall that nostalgic (fuzzy) memories of towns built around (and thus dependent on) a single factory or industry tend to ignore some of their harsh realities. A recent New York Timesarticle documenting life in Eden, North Carolina—home of the famed “Karastan rug”—hits several of these points, which I’ve excerpted below:

The company already had mills nearby, and the new site — a former furniture factory along the Dan River — offered plenty of water for textile finishing. But the new mill needed land for expansion and chose a Black neighborhood nearby, displacing much of the population. The expanded mill was built, along with 166 cottages, to house what at the time was an all-white work force. Textile mills were segregated until the 1960s, and Black workers were excluded from production jobs until then….

By the time Ms. Galloway began working in the late 1960s, the mills no longer rented out houses to workers, deducting the rent directly from their pay as they had until the 1940s, but Eden was still very much a company town….

Mill work, especially in a right-to-work state, can be dangerous on many levels, from machinery mishaps to byssinosis (brown lung disease) to violent conflicts that have occurred when workers attempted to unionize.

An old YouTube video shows some of the same issues:

Similar stories pervade steel (even today), coal, furniture, and other labor-intensive industries that have long been targeted by federal protection.

As my former Cato colleague Brink Lindsey documented back in 2009 (when “nostalgianomics” was all the rage on the left, not the right), rose-colored reminiscing about the “good ol days” of the 1950s and ‘60s also tends to ignore “the widespread cartelization efforts of the thirties, farm supports, price and entry controls on large sectors of the economy, restrictions on retail competition, high trade barriers, racist immigration laws, and the sexist confinement of working women to a pink collar ghetto.” So, sure, these towns did provide certain residents with stable jobs and good pay, but those jobs also had serious downsides; many Americans were barred from working them; and communities dependent on a single company or industry could be both exploitative and fragile in the face of various economic shocks—foreign or domestic. On that last point, the Times notes that Eden, North Carolina used cheap labor and natural resources to poach Marshall Field’s textile business, which spawned Karastan, from Illinois. And North Carolina furniture-makers did the same to mill towns in New England and Michigan.

Moving On

Fortunately, there is plenty of evidence that most industrial cities and towns in the United States that faced intense disruption—whether due to trade, technology, changing consumer tastes, or corporate consolidation—have since adjusted and are today doing pretty well. As I wrote last year, for example, several studies show that—following the “China Shock” disruption of increased Chinese import competition during the 00s—most U.S. regions eventually ended up better off in terms of economic output and jobs (though some localities with high concentrations of less-educated workers did struggle). A 2018 Brookings Institution report, moreover, found that 115 of the 185 U.S. counties identified as having a disproportionate share of manufacturing jobs in 1970 had “transitioned successfully” away from manufacturing by 2016, and that, of the remaining 70 “older industrial cities,” 40 exhibited “strong” or “emerging” economic performance between 2000 and 2016. The “strong” localities included not only well-known success stories like Pittsburgh and places close to “superstar cities” like Boston and Manhattan, but also smaller places like Beaumont, Texas, Waterloo, Iowa, and Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

Anecdotal evidence reiterates these findings: Townsacross the country that once depended on low-skill manufacturing are now home to a diverse array of companies that succeeded by adapting to the market. The Atlantic’s James Fallows documented several of these communities in his 2018 book, Our Towns, The Story of a Journey, and of an America That Works, which has just become an HBO documentary. In my backyard, the New York Times just wrote about several smaller cities and towns here in North Carolina that—once reliant on textiles, furniture, or tobacco—are reinventing themselves today:

Rocky Mount isn’t the only mill town in North Carolina trying to revitalize its economy. In High Point, Greensboro and Winston-Salem, a region known as the Piedmont Triad, other large factories that once served as economic engines providing many blue-collar jobs are being turned into vibrant mixed-use complexes for work and play. The projects have been designed to connect struggling regions to a new economy based on technology, information and innovation.

Now, with the rise of remote work, developers are betting that the factories’ beauty and sense of history, packaged with a roster of community activities, will give them a way to lure young talent. If workers are no longer tethered to their offices, they’re free to go anywhere — and it’s possible they will choose smaller cities with a higher quality of life.

As the Times notes, Winston-Salem—where seemingly everything is named after RJ Reynolds Tobacco and Hanes Apparel (and where my in-laws live)—is a testament to what’s possible:

Today, just about all of the warehouses, factories and other industrial facilities have been renovated in a 2.1-million-square-foot complex called Innovation Quarter. The buildings are home to the health system’s labs and the university’s medical and engineering schools, as well as companies like the I.T. firm Inmar and dozens of start-ups — all tightly clustered around a small green space.

Innovation Quarter is no moribund research park. Thousands of workers and students cross its 330 acres daily, and its administrators maintain a busy schedule of yoga classes, food trucks and lunchtime concerts in the park. That dynamism has transformed the rest of Winston-Salem, which now boasts a busy downtown with significant residential growth. The city gained workers during the pandemic, according to a McKinsey report.

Easily my favorite example of this adjustment is former textile town Greenville, South Carolina, and its next door neighbor, Spartanburg. I’ve tweeted and written a lot about the Greenville-Spartanburg area in the past few years, but two recent articles from the Wall Street Journal and commercial real estate magazine CoStar highlight the city and its transformation from a dying (and polluted) city dependent on textiles to a dynamic, beautiful place featuring both multinational manufacturing—anchored by Michelin and BMW—and high-skilled services like banking and tech. Now, once-blighted downtown Greenville real estate is, per CoStar, booming: “Michelin brings in people from France, BMW draws from Germany and TD Bank, based in Toronto, brings executives from Canada. The buyers of the pricey townhouses downtown are from cities such as Chicago and Washington, mostly retirees or people buying second homes.” With these folks comes new housing and services (restaurants, etc.), further supporting and enriching the local economy. Locals tell me it’s downright cosmopolitan (gasp!) there today.

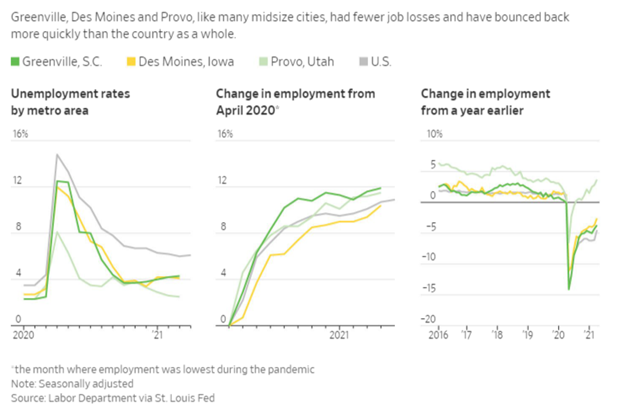

The Journal adds that—much like the North Carolina towns noted above—Greenville and many other smaller cities, such as Des Moines, Provo, Madison, Wisconsin; and Fort Myers, Florida; are further benefiting from pandemic-induced shift to remote work and many Americans’ newfound desire to leave major urban centers:

Even before Covid-19, these rising stars… had been quietly building out vibrant economies in the shadow of bigger metropolises. During the pandemic, they have drawn workers and businesses with large and affordable homes, ample access to outdoor space and less congestion.

They also have a mix of high-tech jobs and old-line industries, including manufacturing and finance, that turned out to be more resistant to the downturn. They came through the year with fewer job losses and service cuts, and made quicker recoveries.

Each of these places has rebounded in different ways and with different industries, and certainly state and local government efforts have played a role, but the overarching themes for all of them remain the same: adjustment, flexibility, and diversification beyond the industry or company that once defined them in the supposed “Good Ol’ Days.”

And Then There’s Youngstown

These cities and towns across American also stand in stark contrast to struggling Lordstown and its next door neighbor Youngstown, whose steel-town history Wikipedia helpfully summarizes:

Between the 1920s and 1960s, the city was known as an important industrial hub that featured the massive furnaces and foundries of such companies as Republic Steel and U.S. Steel. At the same time, Youngstown never became economically diversified, as did larger industrial cities such as Chicago, Pittsburgh, Akron, or Cleveland. Though population levels remained flat for a few more decades, population had not grown since the Great Depression, though General Motors had opened Lordstown Assembly in 1966 to help offset some losses. Hence, when economic changes forced the closure of plants throughout the 1970s, the city was left with few substantial economic alternatives.

Today, Youngstown is still home to a couple steel companies, including French-owned Valourec, and is still the subject of nostalgic pieces on its long-gone glory days as a hub for American steel production. Rarely (if ever) mentioned, however, is that the still-depressed Youngstown area has also, as recently documented by Bloomberg, been the target of massive amounts of federal assistance since the late 1970s—taxpayer dollars almost uniformly seeking to restore Youngstown to its past manufacturing glory:

For decades, this corner of Ohio has been held up by everyone from Bruce Springsteen to Donald Trump as an emblem of industrial decline and what’s gone wrong in America. A succession of presidents has promised—and failed—to turn around Youngstown, which, despite all the political attention and federal dollars lavished upon it, doesn’t have a supermarket in the residential neighborhoods closest to downtown.

In his 2013 State of the Union address, Barack Obama singled out Youngstown as an example of one route to industrial revival. Four years later, Trump came to town. The jobs are coming back, he told a crowd of supporters: “Don’t sell your house.” In 1990 more than 61,000 people were employed in manufacturing in the Youngstown metropolitan area. When Obama gave that address to Congress, the number was 29,895. By March of this year, the number was 23,128….

But the history of grand revitalization plans doesn’t bode well for actually generating the jobs needed or being promised. “The fact is there’s the political narrative, and then there’s the economic reality,” Sumell says. “They’re never the same, and they are often just factually opposed to one another.”…

Among Trump’s actions, of course, were his attempts to strong-arm GM into keeping its Lordstown plant open and then, after that failed, to help facilitate its sale and conversion into Lordstown Motors. He even held a big photo op with a Lordstown Motors prototype at the White House, taking credit—as usual—for both the plant and the revival of the now-“booming” surrounding area.

Last year, Ohio Sens. Sherrod Brown and Rob Portman also took a little credit (again as usual) for the Lordstown announcement, but now Brown finds the latest news “concerning”—though he’s of course still quite eager to “support Lordstown Motors’ efforts to secure an Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Loan from the Department of Energy.” At this point, the EV company’s story still hasn’t been written but—let’s face it—things aren’t looking great.

Youngstown thus continues to stand as a shining example—unfortunately—of the limits of federal policy in resuscitating old industrial cities. Indeed, as the Peterson Institute’s Adam Posen recently explained in Foreign Affairs, “there are precious few examples of a government successfully reviving a community suffering from industrial decline.” He cites failed U.S. efforts to revive the Massachusetts textile towns of Lawrence and Lowell, and similar efforts in the Midwest to do the same. Posen goes on to detail similar failures to revive struggling communities or regions in Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and even China—“a country that has protected heavy industry on an unprecedented scale for years on end, has run substantial manufacturing trade surpluses, and has a government willing to restrict internal migration and locate industries by edict.”

Posen and I don’t necessarily agree on the tax, labor, and regulatory policies that government should enact to help struggling American communities and workers, but we do wholeheartedly agree that—leaving aside whether national economic interventions should relieve states and towns of their responsibilities to create viable commercial centers—there’s little evidence they can.

Compare and Contrast

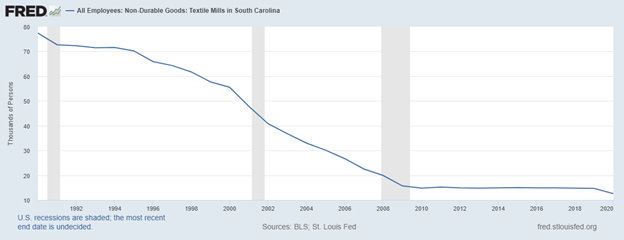

The contrast between still-struggling Youngstown and now-thriving Greenville is particularly apt, as each town once relied on an industry that has been a traditional recipient of federal government support yet has shed tens of thousands of American jobs—especially in Ohio and South Carolina:

As we discussed a few weeks ago, steel’s been one of the most protected and subsidized industries in the country for decades, and the textiles and apparel industry received similar protection. However, these industries are also different in one key way—as indicated in the chart below (and in the previous newsletter), U.S. steel industry production (not workers) has remained relatively steady in recent years, while textiles and apparel production has continued to decline:

Today, the steel industry still has a large share of the total U.S. market (it was more than 70 percent before Trump’s tariffs) and—of course—still has substantial political clout and tons of tariff protection. By contrast, the domestic textile and apparel industry has evolved into a relatively smaller player making high-end products and importing the rest, as some U.S. trade barriers receded and the remaining ones were overwhelmed by seismic forces affecting the industry in every developed country around the world. In short, the textile and apparel industry still gets too much federal love, but it’s just not in the same league as Big Steel these days. And the numbers and policies back that up.

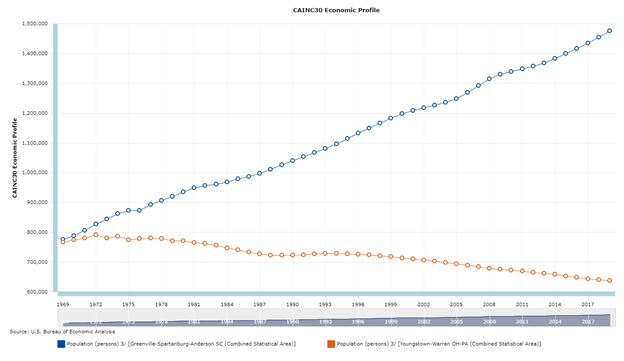

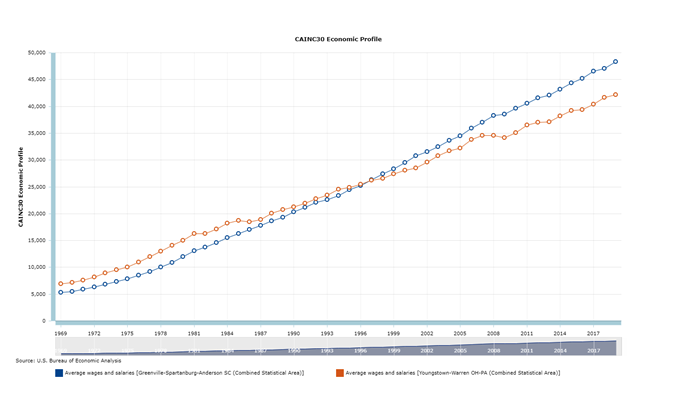

At first glance, the continued dominance of Big Steel in the United States would appear to be a victory for protectionism and the politicians like Trump, Brown, and Portman repeatedly promising to revive Youngstown and other “Rust Belt” towns with federal support. However, as the charts below from BEA show, all those promises—not to mention the subsidies and tariffs—have done little for Youngstown, which has experienced economic stagnation (population, jobs, and GDP) since the 1970s. Meanwhile, those same charts show that the demise of the textile industry in South Carolina and the resulting diversification away from the industry—may have been a godsend for once-similarly-situated Greenville (where average earnings went from greatly lagging to far exceeding those in Youngstown) over the same period.

(Note: BEA’s regional GDP data don’t go back any further.)

Surely, this divergence isn’t just about steel and textiles or even the federal policies targeting them, but that’s precisely the point: The contrast between Greenville and Youngstown—and the contrast between many thriving U.S. localities and those still reeling from decades-old shocks—shows that the struggling communities’ problems very likely stem not from “globalization” or “financialization” or a lack of federal support, but from localtax, labor, and other policies and these specific communities’ inability to adjust to big economic shocks, whether foreign or domestic. And in Youngstown’s case, at least, all those federal promises may actually be making things worse—discouraging the community and its residents from undertaking the painful-but-necessary adjustment that places like Greenville undertook years ago to become successful today and be poised for even greater success in the future.

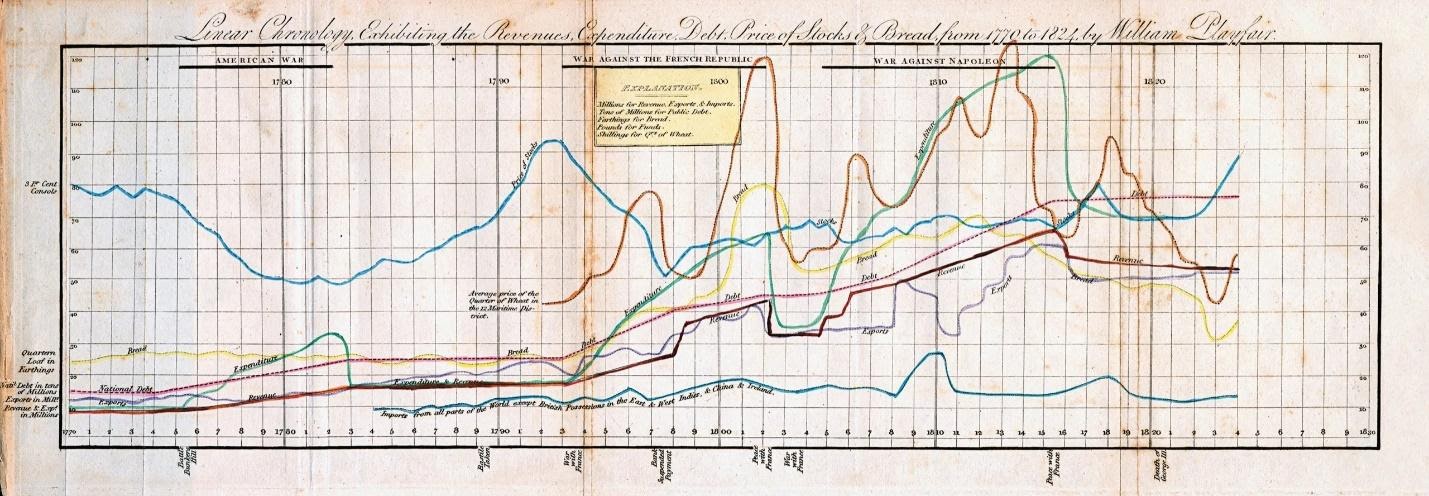

Chart of the Week

The chart that changed the world:

The Links

My new working paper on industrial policy, plus a blog post on steel prices

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.