Dear Capitolisters,

Last week we hit on an issue—Buy American—with wide popular support but little substantive merit. In keeping with that theme, today we’ll examine stock buybacks, which were also a prominent part of President Biden’s recent State of the Union Address and also suffer from the same pervasive lack of understanding (if not moreso) in our current political moment. Indeed, if you spend more than a few minutes thumbing through political Twitter, you’re almost certain to see someone complaining about stock buybacks, tying them to the “current thing” (whatever that may be), and/or promising to tax, regulate, or ban them.

There’s only one small problem: These folks seem to have almost no idea what they’re talking about. Or, as Dartmouth finance professor Ken French once put it (h/t Allison Schrager):

“Buybacks are divisive. They divide people who do understand finance from those who don’t.”

First, the Basics

Before we get to that, however, let’s go over some basics (significantly truncated for brevity, so don’t #ButActually me, finance dorks). When deciding how to pay for business operations and potential long-term capital investments, publicly traded corporations generally have three choices: debt (bonds or loans), equity (stocks), and/or cash (assuming the company is profitable). Whether to pursue a certain investment and how to source the necessary capital is a core aspect of corporate finance:

A company may borrow from commercial banks and other financial intermediaries or may issue debt securities in the capital markets through investment banks. A company may also choose to sell stocks to equity investors, especially when it needs large amounts of capital for business expansions.

Capital financing is a balancing act involving decisions about the necessary amounts of debt and equity. Having too much debt may increase default risk, and relying heavily on equity can dilute earnings and value for early investors. In the end, though, capital financing must provide the capital needed to implement capital investments.

Corporate finance departments also decide whether some profits should be returned to shareholders, via either a dividend or a share repurchase (buyback), instead of being held by or plowed back into the company. For dividends, all shareholders get cold, hard cash—pretty simple. For buybacks, on the other hand, a company purchases its own shares from existing shareholders on the open market (typically at a premium) and then cancels the repurchased stock. This benefits the remaining shareholders by reducing the number of shares in circulation and increasing their stake in the company. In contrast to a dividend, however, shareholders who don’t sell their shares don’t pay any tax (directly, at least) on the shares’ increased value, if any. They would pay, however, standard capital gains taxes whenever they sell.

Whether to issue a dividend or buy back stock (or do nothing) is a strategic decision specific to the company at issue, and it depends on a wide range of internal and external factors, such as current market conditions, the cost of capital, potential investment opportunities, the company’s current stock price and investor perceptions, the company’s recent performance and long-term vision, the company’s bylaws or optimal capital structure, the tax laws applicable to the company and its shareholders, and so on. There’s no single right answer, and smart decisions today can look dumb in retrospect (e.g., when market conditions quickly change in unexpected ways). But—and here’s the key—there’s nothing inherently “good” or “bad” about these decisions; it’s just what corporate finance departments do.

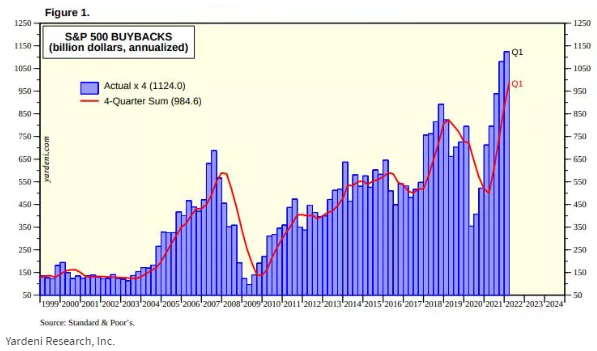

Anyway, although dividends remain the more common way to return cash to shareholders, buybacks have increased in recent years, hitting almost $1.2 trillion in the first quarter of 2022:

As buybacks have become more popular, they’ve also become a target for criticism—especially by populist politicians and pundits who complain that buybacks not only enrich “elite” CEOs and shareholders but also inflict broader economic harms by draining public corporations of potential investment dollars, fueling inequality, and so on. Thus, the IRA (the bill that shall not be named) sought to discourage the practice by imposing a 1% excise tax on public company stock buybacks above $1 million (and meeting other criteria), and—perhaps because the 1% tax doesn’t seem to be discouraging buybacks so far—President Biden proposed quadrupling that tax in his very populist State of the Union address. Here’s how the White House’s SOTU Fact Sheet justified the proposal:

Stock buybacks enable corporations to funnel tax-advantaged payouts to wealthy and foreign investors, instead of paying dividends that shareholders are required to pay taxes on. In addition, a number of experts have argued that CEOs—who are compensated mostly in stock—use buybacks to enrich themselves to the detriment of the long-term growth of the company. Last year, oil and gas companies made record profits and invested very little in domestic production and to keep gas prices down—instead they bought their own stock, giving all that profit to their CEOs and shareholders. President Biden signed into law a surcharge on corporate stock buyback, which reduces the differential tax treatment between buybacks and dividends and encourages businesses to invest in their growth and productivity as opposed to paying out corporate executives or funneling tax-preferred profits to foreign shareholders.

Buybacks are also frequently tied to—or even blamed for—various crises: Back when Abbott Labs first closed its baby formula plant, for example, Sen. Ron Wyden complained that it “chose spending billions on buying back its own stock instead of investing in critical upgrades to a plant essential to feeding our nation’s infants.” Folks are now following the same playbook with the train derailment in Ohio:

And, lest you think only the left targets buybacks, fear not: Populists on the right have also sought to ban buybacks, complaining that they detract from investment, enrich insiders, and allow for tax avoidance—just like the left (lessons abound).

Are Buybacks Good or Bad? (Spoiler: They’re Neither.)

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, I regret to inform you that the populists are mostly mistaken—often wildly—when it comes to the evils of stock buybacks. Yes, of course, some buybacks can prioritize short-term profits and corporate insiders over sound financial moves, but the idea that they are systemically corrupt or economically harmful (and thus deserve to be banned) suffers from major flaws.

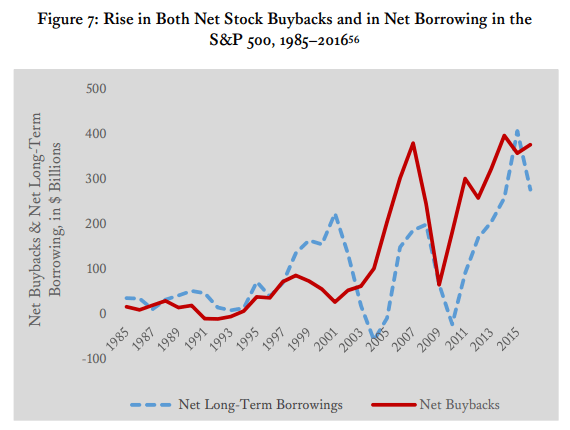

First, there is no reason—either theoretically or empirically—to believe that buybacks prevent corporations from financing major capital investments, increasing worker pay, or otherwise thriving in the future. As already noted, corporations have multiple ways to finance their business operations, including via cash, equity, or debt—the last of which has been very attractive in recent years, thanks to extremely low interest rates. Indeed, Harvard’s Mark Roe found that the post-Great Recession increase in buybacks was essentially offset by new, ultra-low-rate debt (borrowed “nearly for free”) that also carried certain tax benefits. He thus concludes that “corporate America recapitalized its balance sheet with cheap debt” instead of equity, while its net cash position (i.e., money that could be spent on equipment, workers, etc.) remained basically the same. Money, it turns out, remains fungible. (BREAKING, I know.)

Roe adds that, for the same reason, “Worldwide evidence shows that buybacks increase with low interest rates (and decrease with high rates).” It’s thus no surprise that we’ve seen an explosion in buybacks since COVID-19 tanked the economy in 2020 and central banks adopted ultra-easy monetary policy in response.

Whether this recapitalization was a smart move is a firm-specific decision based on corporate finance pros’ views of internal and external factors. But there’s no theoretical or practical reason to assume that buybacks and expansions/investment can’t happen simultaneously.

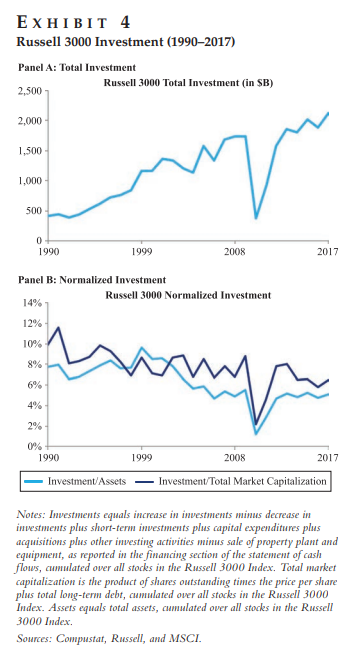

In fact, plenty of evidence shows that increases in share buybacks have not undermined corporate performance and often coincide with rising business investment. In a 2018 paper, for example, Cliff Asness, Scott Richardson, and Todd Hazelkorn found that the last run-up in buybacks didn’t cause companies to “self-liquidate” (finding much the same as Roe did above); didn’t “starve investment”; didn’t fuel major stock price gains (they typically go up by only 1 or 2 percent); and didn’t cause “artificial” increases in earnings-per-share (and thus stock prices). In short, the data implode the populist caricature of rapacious corporate insiders using buybacks to cannibalize their companies and pad their performance-based compensation.

Perhaps most notably (given the current political rhetoric), these authors found that “normalized” investment by companies on the Russell 3000 index didn’t fall as buyback activity increased and, in fact, “both investment and share repurchases have increased since the end of the financial crisis.”

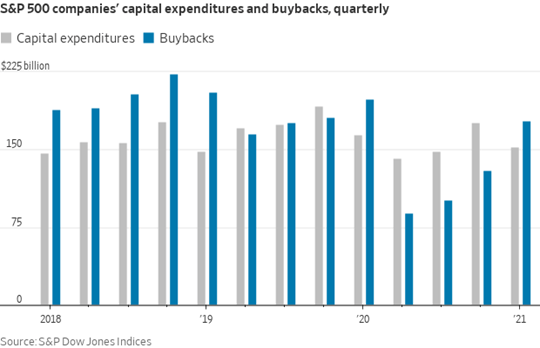

Since then, buybacks and firms’ capital expenditures again increased simultaneously:

And firms’ balance sheets are in good shape:

As AEI’s Jim Pethokoukis noted a few weeks ago, moreover, empirical evidence from a 2019 JPMorgan analysis also undermines the idea that buybacks undermine companies’ long-term financial performance (emphasis mine): “[If] companies truly were unwisely diverting money from profitable investments in order to do buybacks, then they would likely underperform over the long term, but this is not the case. Stocks of companies that buy back their shares tend to outperform both short and long term according to J.P. Morgan and independent research.” Corporate elites, it turns out, didn’t just sell off their companies for spare parts and walk away. (Shocking, I know.)

Second, anti-buyback populists seem not to grasp that money delivered to shareholders, whether through buybacks or dividends, isn’t just buried in their backyards—it’s almost always reinvested by shareholders elsewhere in the U.S. economy. This, again, is a business-specific decision that can reflect well on a company, as French explained in a recent interview:

The easy way to think about a buyback and why we see a positive price response when there are buybacks. If I'm a manager of a company, we produce lots of earnings, we've got lots of cash in the vault, we're trying to decide what to do with it. And I look out there and I say, man, this coronavirus is really going to cripple the economy, I don't see any positive net present value projects that I want to invest in. I can keep this money in the vault, which isn't really a good investment either. I mean, that is an investment leaving money in your vault, or I can go out and give it back to my shareholders.

An easy way to give it back to my shareholders is to go out and buy stock. So when I see a company buying stock, what I say is, "Oh, this is a manager who's representing their shareholders well and doing the best thing they can with their shareholder's resources. And the manager has decided the best thing she can do with it is go out and repurchase shares. And that's why the market price goes up because people are saying, "Oh, this is a manager that's respecting the shareholders." And saying, "I don't have anything better to do with it, I'm going to buy up these shares."

As my Cato colleague Adam Michel recently noted, this capital reallocation can also be a good thing for the U.S. economy overall by allowing cash to flow to more potentially more productive investments (emphasis mine):

Stock buybacks and dividend payments are typically larger and more frequent when businesses are older, well established, and no longer growing rapidly. This happens because businesses generally buyback shares after their investment needs are met. Thus, stock buybacks return unused resources to individual investors so that they can be redeployed at higher growth firms where the marginal investment will produce more jobs and bigger economic gains. According to one estimate, about 95 percent of resources returned through stock buybacks are reinvested in other public companies. If policymakers were to entirely ban stock buybacks and dividend payments, it would trap these profits at large incumbent firms, ossifying markets and starving smaller firms of needed capital.

As financial journalist Roger Lowenstein explained in 2021, “Buybacks are simply a means, via the intermediary of investors, of reallocating capital from companies with a surplus to companies with a capital need. And too much capital can be just as harmful as too little, leading to a misallocation and a waste of social resources.”

Whether shareholders end up investing their new cash wisely is of course going to depend on all sorts of factors. But it’s mind-numbingly obvious (to me, at least) that corporate finance pros and major institutional investors will be better than the government at making these decisions (and at determining their company’s proper capital structure)—especially when it comes to the pros’ own businesses! In that French interview, for example, his colleague had found that companies engaging in buybacks or dividends “look very similar in terms of being low priced stocks with good profitability that invest conservatively.” French’s response is illuminating:

Yeah. To really go back and answer your question, should the government penalize companies that are doing that? If they did that, that would be like saying we insist these companies go and take negative present value projects. Governments ought to be in the business of encouraging companies to make good investments not squandering their shareholders or their citizens' resources.

Indeed, populists worried about corporate power and market concentration should be cheering the capital reallocation spurred by buybacks. The Manhattan Institute’s Schrager uses the excellent example of oil companies (emphasis mine):

Biden is angry that oil companies did buybacks this year after raking in large profits. He says they should have used that money for more exploration and expanding refining capacity to boost the supply of oil. But why would an oil company invest in infrastructure to increase production when the administration has openly stated that it hopes to eliminate fossil fuels in the next decade? A rational response—one that maximizes shareholder value—is to return money to shareholders, not to make a large investment in something that may be worthless in the not-too-distant future. Biden should be delighted the profits are getting returned to shareholders, who will now invest in industries his administration finds more palatable.

Burn.

Banning buybacks would not prevent companies from returning cash to shareholders or rebalancing their capital holdings away from equity. It’d just make doing so more difficult: shareholders could get corporate cash from dividends, but those would be immediately taxed; corporations could use a “reverse stock split” to reduce the number of available shares, but those are typically reserved for companies in distress. Why would the government want to make these moves—and the resulting capital reallocation—harder? It makes no good sense.

Summing It All Up

At the end of the day, share buybacks are one relatively simple part of the very complicated world of corporate finance. As Lowenstein notes, they don’t destroy investment or harm the economy any more than a decision by a public company to sell any stock at all: “If it is not wrong for a corporation to sell $3 billion in stock, is it wrong for it to sell $4 billion and later buy back $1 billion? In the end, it is the same thing.” That $1 billion in buybacks might—as he and many others acknowledge—be a business mistake or emerge “from a misbegotten obsession with short-term stock prices.” But it surely doesn’t have to be; there’s no good empirical evidence that it’s happening on a regular, market-moving basis; and neither President Biden nor his fellow populists have even attempted to distinguish between the “bad” buybacks and the (probably more plentiful) “good” ones. It’s just evils all the way down.

Maybe that’s good politics, but it’s a recipe for miserable policy.

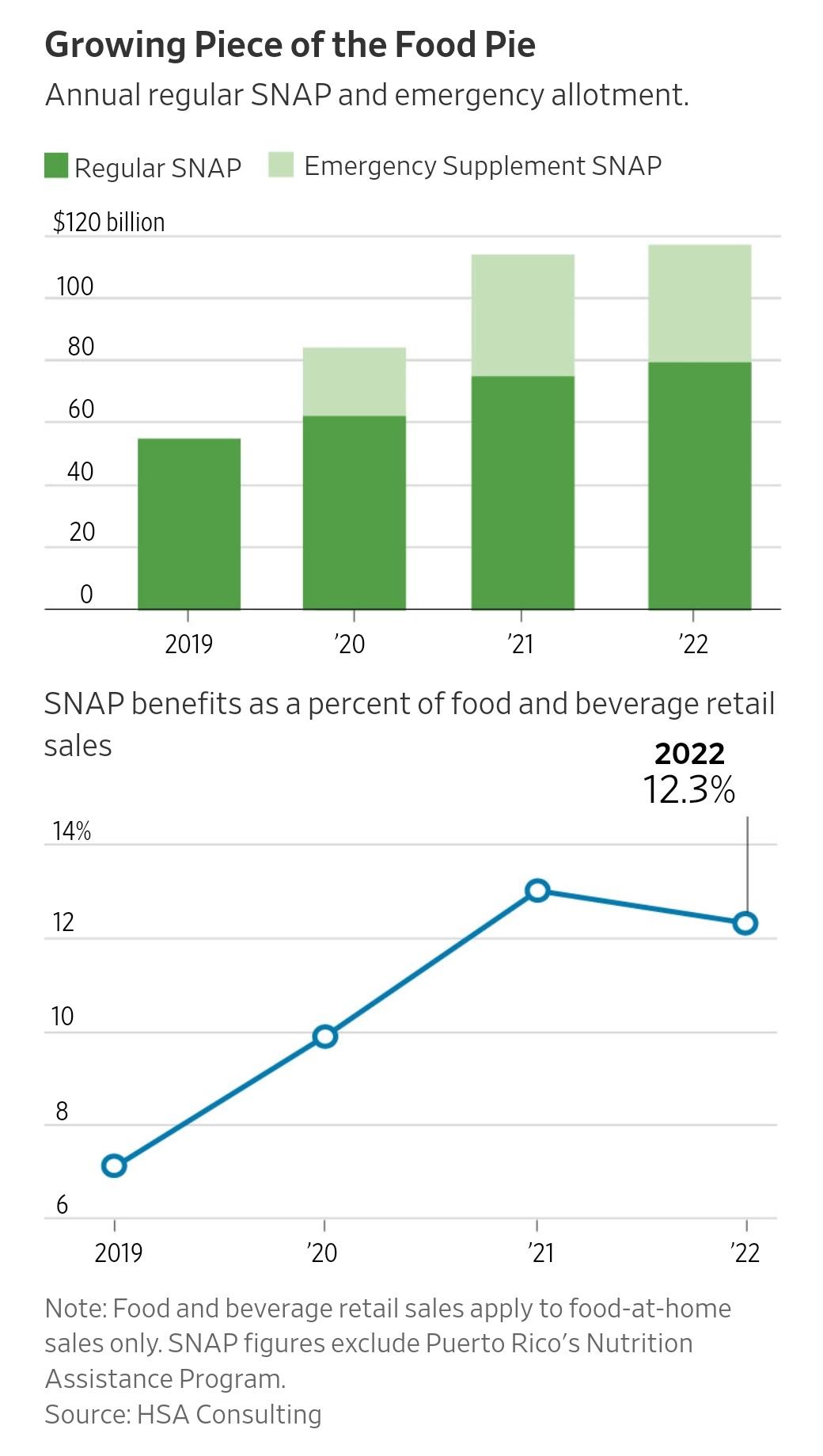

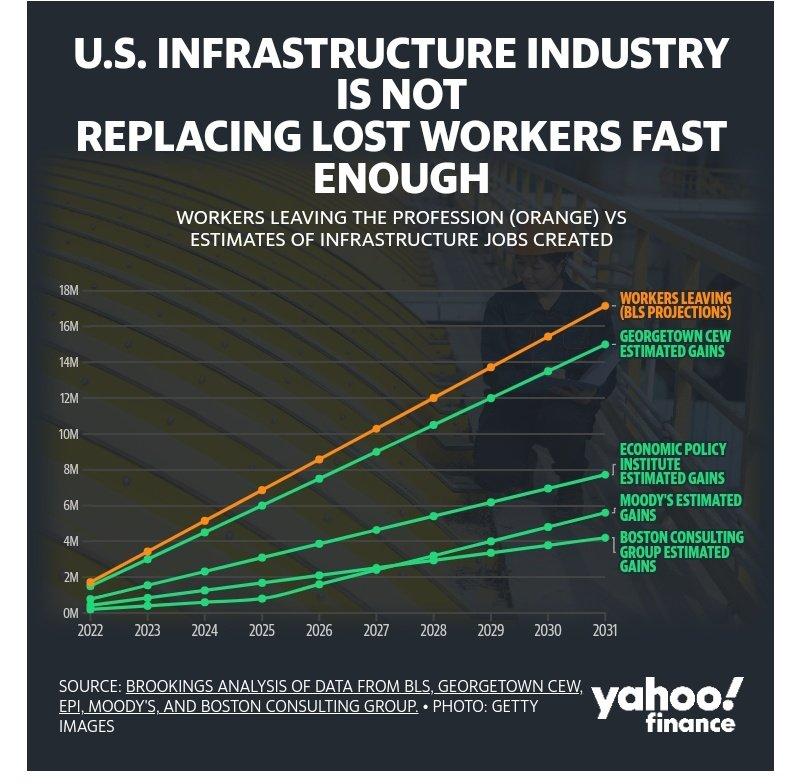

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.