My father is an incredibly gifted teacher. Until he retired to become a cattle farmer (true story—that’s what he does now), he was a math professor. He spent most of his career at Georgetown College, a small Baptist college near Lexington, Kentucky. At one point, he was so popular that when students were asked to vote on a faculty member to give the commencement address, he received an absolute majority of votes cast (not a plurality) in spite of competing against dozens of colleagues.

In church, his Sunday School classes were always packed. I’ll never forget his biggest class. After multiple ordeals within the strange hothouse of faculty infighting, he developed a curriculum for a class called, “The Christian and on-the-job politics.” It was a great idea (I’ve got a strong pro-Dad bias here, so hang with me), and it created an actual buzz in the congregation. I skipped my youth group to attend the first class. There weren’t enough seats. Folks lined the walls.

He started the class with something he called the “LBALAG principle.” When confronted with the “Lesser Bad,” he asked, “Shouldn’t the Christian be at Least as Good?” He walked through verse after verse of Christ and the Apostles advocating love in the face of hate, blessings in the face of persecution, kindness in the face of intolerance, put it in the historical context of violent, state-sanctioned murder of Christian believers, and said, “Given our far lesser challenge in our own workplaces, can’t we be as least as loving and at least as kind as these first Christians?”

He took a lesson about “dealing with” or “coping with” bad bosses or malicious co-workers and transformed it into a lesson about loving bosses and caring for co-workers. He made the point that you can never, ever divorce goals from methods, ends from means. It made a powerful impact on my high-school mind. It convicted me. How fragile was my love for others when I struggled with basic kindness even while living a life of ridiculous privilege?

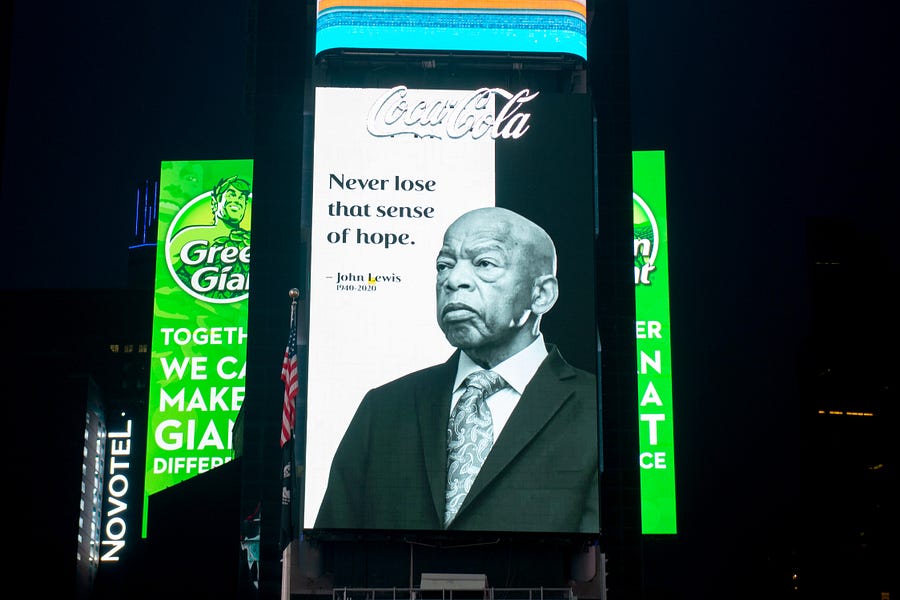

I think of that lesson often. I thought of it again when John Lewis was laid to rest.

My Sunday newsletter two weeks ago argued that all too many Christians lack a robust political theology. We think of political engagement primarily through the prism of issues and secondarily (if at all) through serious consideration of methods. In politics, we tend to ask far more, “What should a Christian believe?” than consider, “How should a Christian behave?”

I touched on this on the weekend when Lewis died, but how many times in American life have we seen a better marriage of Christian belief and Christian behavior than the nonviolent resistance to segregation and Jim Crow in the American South? Remember Lewis’s own words, from a 2004 interview:

During those early days, we didn’t study the Constitution, the Supreme Court decision of 1954. We studied the great religions of the world. We discussed and debated the teachings of the great teacher. And we would ask questions about what would Jesus do. In preparing for the sit-ins, we felt that the message was one of love — the message of love in action: don’t hate. If someone hits you, don’t strike back. Just turn the other side. Be prepared to forgive. That’s not anything any Constitution say anything about forgiveness. It is straight from the Scripture: reconciliation.

In his legendary “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King Jr. didn’t just deliver a master class on the injustice of segregation, he also delivered a lesson in the method of nonviolence, of the graduated approach before he took to the streets. “In any nonviolent campaign,” King wrote, “there are four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self purification; and direct action.”

And he appealed of course to scriptural principle and scriptural example:

One who breaks an unjust law must do so openly, lovingly, and with a willingness to accept the penalty. I submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law.

Of course, there is nothing new about this kind of civil disobedience. It was evidenced sublimely in the refusal of Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego to obey the laws of Nebuchadnezzar, on the ground that a higher moral law was at stake. It was practiced superbly by the early Christians, who were willing to face hungry lions and the excruciating pain of chopping blocks rather than submit to certain unjust laws of the Roman Empire.

Moreover, it’s important to remember that the civil rights movement’s success was hardly assured. In other words, the fact that the tactics “worked” is not the reason they were justified. They were right regardless of the outcome. And they were pursued against great odds.

What looks inevitable in hindsight was anything but certain. In fact, if you were placing contemporary bets on a political outcome, would you guess that some version of a three-century status quo would prevail, or that the civil rights movement would achieve a legal revolution nearly on par with emancipation itself?

At the same time, can we even recall a modern Christian political movement so consistent with the upside-down logic of biblical Christianity? To gain your life you must lose your life. Bless those who persecute you. Love your enemies. The last shall be first.

In fact, the turning point of the movement came in 1963, in the Birmingham “Children’s Crusade,” when the least-powerful members of Southern society, the black children of Alabama, confronted Bull Connor’s dogs and firehoses, and—finally—shocked the conscience of a nation chock full of Christians and moved it to take decisive legal and political action.

That’s what a Christian political theology looks like in action. Both ends and means are suffused with Gospel truth.

Now, let’s return to the LBALAG principle and reflect just a bit on contemporary Christian political action. In the face of less evil than the systematic segregation, lynching, and comprehensive violation of basic human rights that characterized the Jim Crow South, are America’s contemporary political Christian leaders behaving at least as good as these civil rights-era heroes?

Or are we frequently responding with a degree of fear and panic and compromise that’s mystifying in its historical context?

In 2016, one of the things that we learned was that Donald Trump’s rise first owed its real strength to the irreligious right—the segment of the Republican electorate that attended church the least. For example, in March 2016, a Pew poll “found that Trump trailed Ted Cruz by 15 points among Republicans who attended religious services every week. But he led Cruz by a whopping 27 points among those who did not.”

In early 2017, The Atlantic’s Peter Beinart wrote a prescient, important essay noting the negative cultural effects of our increasingly secular politics, on both the left and the right. Far from ushering in a new, more tolerant political dawn—secularization was creating a far more vicious political reality.

Here’s Peter, first speaking about the right:

Secularism is indeed correlated with greater tolerance of gay marriage and pot legalization. But it’s also making America’s partisan clashes more brutal. And it has contributed to the rise of both Donald Trump and the so-called alt-right movement, whose members see themselves as proponents of white nationalism. As Americans have left organized religion, they haven’t stopped viewing politics as a struggle between “us” and “them.” Many have come to define us and them in even more primal and irreconcilable ways.

And next, speaking about the left:

The decline of traditional religious authority is contributing to a more revolutionary mood within black politics as well. Although African Americans remain more likely than whites to attend church, religious disengagement is growing in the black community. African Americans under the age of 30 are three times as likely to eschew a religious affiliation as African Americans over 50. This shift is crucial to understanding Black Lives Matter, a Millennial-led protest movement whose activists often take a jaundiced view of established African American religious leaders. Brittney Cooper, who teaches women’s and gender studies as well as Africana studies at Rutgers, writes that the black Church “has been abandoned as the leadership model for this generation.” As Jamal Bryant, a minister at an AME church in Baltimore, toldThe Atlantic’s Emma Green, “The difference between the Black Lives Matter movement and the civil-rights movement is that the civil-rights movement, by and large, was first out of the Church.”

And given the tenor of the times, these words from Beinart are downright prophetic:

Black Lives Matter activists may be justified in spurning an insufficiently militant Church. But when you combine their post-Christian perspective with the post-Christian perspective growing inside the GOP, it’s easy to imagine American politics becoming more and more vicious.

It is now increasingly clear that the un-Christian de-linking of ends and means is working its dark magic on the United States of America, including on the American church. When confronting lesser evils, our political selves are behaving far worse than we should, and there’s strong evidence that the religious right is now joining the irreligious right on the march down that dark path. Rather than resisting the de-linking, it’s advancing the degradation of our political culture.

Remember the statistics about churchgoing Republicans rejecting Trump more than their non-churchgoing peers? Well that changed, dramatically. By the time Beinart wrote his essay, white churchgoing Evangelicals supported Trump more than nonchurchgoing Evangelicals, and that gap has now persisted for years. Rather than presenting the last line of defense against his rise, churchgoing Evangelicals are now the foundation of his political power.

What’s the old saying? “If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.” That’s exactly what white Evangelicals did. They didn’t change the post-Christian ethos of Trump’s movement. All too many times they embraced that ethos. And in so doing they have often shocked the conscience of the nation, but sometimes in the worst ways.

As a nation says farewell to John Lewis and is saying farewell to his peers in that great generation of black Christian political leaders, it’s worth remembering that there is a better way. Christian political engagement can look very different than it so often looks today. Yes, later in life John Lewis could be bitterly partisan and sometimes deeply uncharitable, but in those most crucial years, he showed us what Christian political courage looked like. May we remember, and may we learn.

One more thing ...

Speaking of Christian charity, I’d urge you all to watch George W. Bush’s brief eulogy at Lewis’s memorial service. It pays proper tribute to Lewis, without keeping any record of personal wrongs. Lewis, remember, famously boycotted Bush’s first inauguration. This is how to lay down partisan differences to celebrate the best memories of a great man:

One last thing ...

In my quest to send you good music that nourishes the soul, I’ve neglected to send along the best beard in Christian music. I love this song—it communicates the power of encountering Christ in scripture. It’s a power that can transform a person and a nation. Enjoy:

Photograph by Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.