It’s class warfare time in American politics again. And whenever that banner is unfurled, you can sure bet that the fight over unions and their powers will be all around us.

Organized labor is in a deepening period of upheaval. How we earn our livings has for a couple of decades been changing in ways at least as fundamental as in the great industrialization at the turn of the previous century—the one that produced the original labor movement. Now the pandemic is juicing the pace of change. After long understanding “work” as a place, employers and employees are learning what is possible in a world without cubicles and time clocks.

In 2020, just 6.1 percent of workers outside of the government were union members according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s up a tenth of a point from the previous year, but only because total employment dropped so terribly. As the employment market continues to pick up, the 428,000 higher-priced union jobs lost last year will undoubtedly be restored more slowly than most of the 9.6 million jobs erased in 2020. Of course, unions for government workers continue to chug on. Public-employee unions covered 34.8 percent of the nation’s government workforce in 2020, with county and municipal jurisdictions leading the way. After successive rounds of stimulus spending, the 7.2-million-member unionized government workforce is certain to grow this year.

We all know about this dynamic. By securing the rights and protections sought for workers over the past century, the American labor movement burned itself out. With the 40-hour workweek, occupational safety laws, equal opportunity hiring, and other goals met, workers became less and less willing to fork over 3 percent of their paychecks for the privilege of union membership. Private-sector employers also learned it is cheaper and easier to pay workers more and increase benefits to avoid unionization and the encumbrances of contracts. Meanwhile, government worker unions grew in size and power in cooperation with local and state officials whom unions support with contributions, manpower, and votes.

President Biden promises to be a champion for unions and wants to see private-sector union membership expand—but he wants something more, as well. Biden wants what many Democrats have long sought: “a seat at the table” for America’s laborers. His 2020 primary foe Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and others want America to follow the example of Germany and other countries that require corporations to give seats on their boards to union representatives—a move California is already heading toward by setting diversity quotas for board memberships. This is part of a larger project that is less about unions representing workers in search of better jobs but rather unions setting policy.

What’s different now is that an increasing number of Republicans are signing on to the effort.

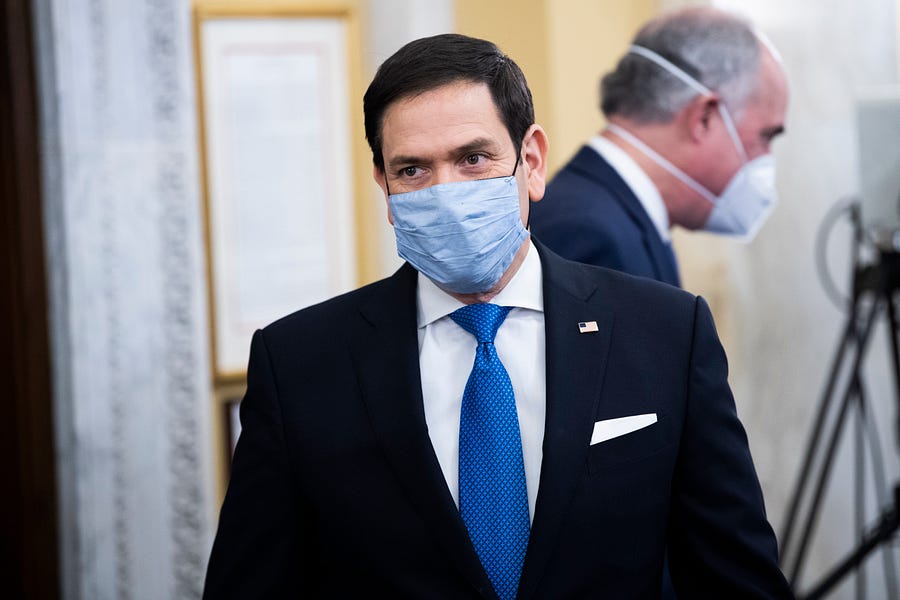

Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, for example, is dabbling in labor organizing. Rubio came out last week in support of a unionization effort aimed at Amazon employees in Bessemer, Alabama, because he says the company has opted

“to wage culture war against working-class values.” Rubio says that he supports the drive because Amazon should be more generous to its workers, yes, but also so that those workers can help steer policy for the company. Rubio points to what he says is unfair treatment by Amazon toward conservative authors as a good reason to organize. In short, Amazon should be unionized so that it will reflect the values of its workers. Just like his Democratic counterparts, Rubio says he knows what those values are and how the companies should be run.

For those of you who guessed that one of the Republican runners up from 2016 would be doing a Walter Reuther impersonation to set up his next presidential run, you've got me beat. But it certainly seems like the moment for Republican class warfare is upon us. Rubio’s fellow Republican pitchforker, Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri, wants a “blue-collar bonus,” which not only separates workers into classes but their employers, too. Big companies would pay the bonus while the taxpayers would make up the difference for workers at smaller firms. But Americans who earn less than the $16.50 an hour Hawley says they are owed don’t all have collars of the same color.

In the United States, we have mostly tried to avoid the idea of settled classes. The American idea of upward mobility is as central to our national ethos as liberty and justice. Talking about “working-class values” or “blue-collar” bonuses suggests that an office temp, a mechanic, a barista, a graduate student and a college kid working a summer job have the same interests. That’s the opposite of the message of traditional conservatism that holds that the government should treat everyone the same regardless of their station in life.

Many Republicans believe that Democrats’ worsening struggle with the middle of the middle class represents the way forward for a GOP that finds itself ideologically adrift after Donald Trump’s departure. Trump and his fellow Republicans certainly have found that culture war issues are very useful at prying blue-collar white voters away from Democrats. The way forward Rubio, Hawley, and others are proposing would match the culture war with a class war.

It may work. But it may also deepen Republicans’ dire problem with the affluent suburban voters who cost them the 2020 election.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.