The Bible tells us we are supposed to pray for our enemies—even the worst of them. Adolf Hitler, Osama bin Laden—there isn’t an asterisk that says, “... unless they’re really bad, in which case, never mind.” I myself have a hard time not wishing ill on people who use speakerphones in public—or, you know, resisting the urge to take active measures.

Hunter Biden isn’t even my enemy. He’s just a garden-variety dumbass with a very famous father. But it still isn’t easy to be sympathetic. Not for me, anyway.

That isn’t something to be proud of. Whatever the madding crowd may try to convince you in 2024, hatred is not a marker of moral seriousness, clarity, or urgency. It’s just a natural itch that it feels good to scratch, and we happen to live in a society that feels the need to moralize its pleasures.

Hatred is not a marker of moral seriousness, clarity, or urgency. It’s just a natural itch that it feels good to scratch.

A big part of our natural moral sensibility is tied up in our expectations of reciprocity. And reciprocity is, of course, a double-edged sword. People who have received kindness and grace may feel obliged to extend kindness and grace in turn—to the sort of people from whom they expect it. People who have received cruelty and pettiness may feel inclined to pay it forward—to the sort of people from whom they expect it. Part of the Christian ethos—something Christianity shares with Stoicism and at least some strains of Buddhism—is intended to move us past that.

That’s a heavy lift. I’ve always liked the legend about Siddhartha Gautama allowing himself to be cheated while gambling, reasoning that this was a way to give aid to the cheater without forcing him to humble himself and beg for charity. That is, indeed, something that one would expect from a great soul.

I myself have … the other kind of soul. And that comes with tendencies that have to be actively resisted.

Reciprocity can lead you the wrong way. Having been myself an object of public interest from time to time, I do not have to wonder what the people who are always going on about their great compassion and empathy would do if I found myself in a difficult situation—I know. These people hate whomever they hate, and I suppose they have their reasons, though I’ve always felt that I am being a little unfair to them: There are some journalists and podcasters and social-media rage-monkeys and such who apparently have very intense feelings about me, while I have no feelings about them at all.

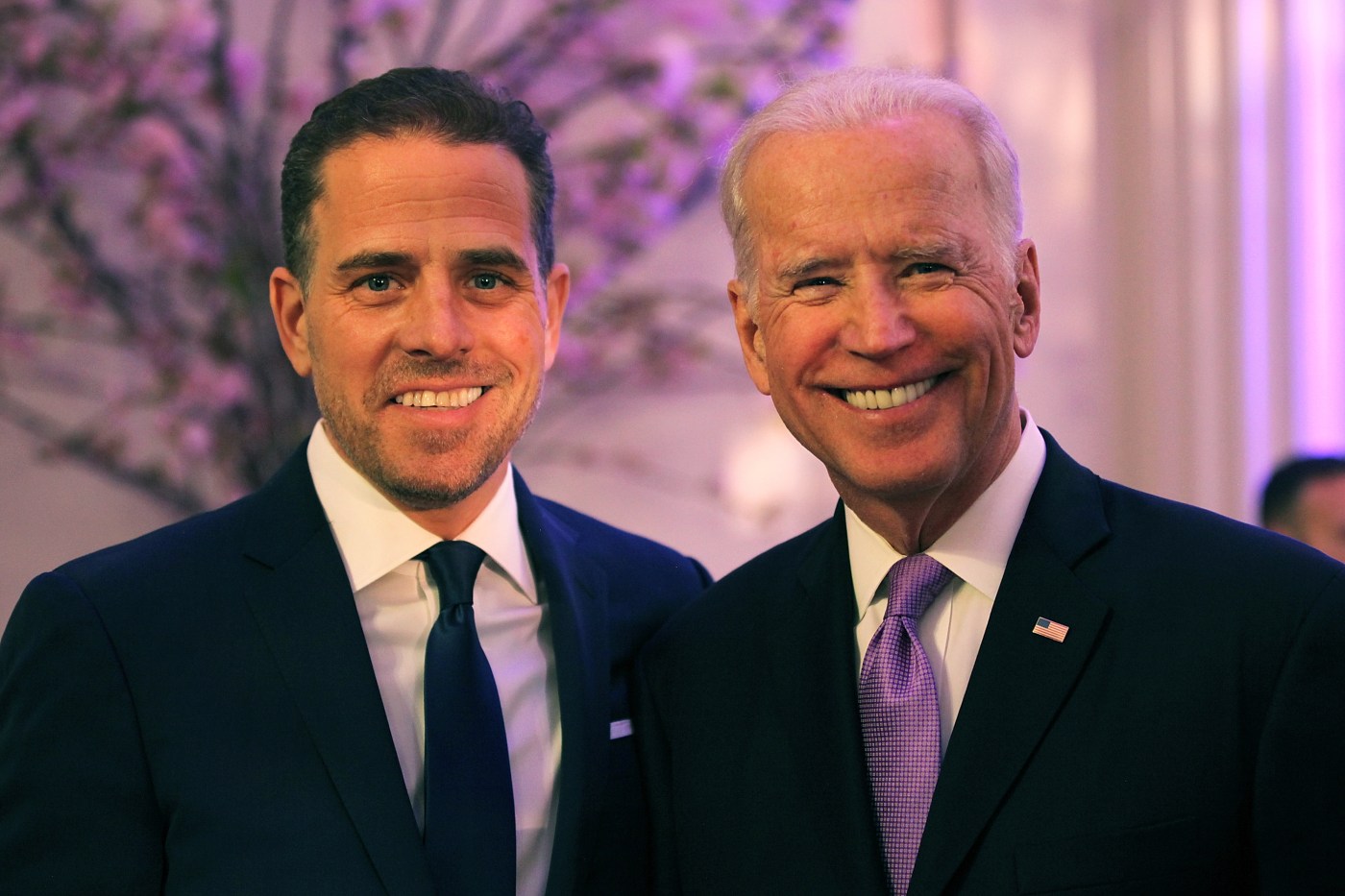

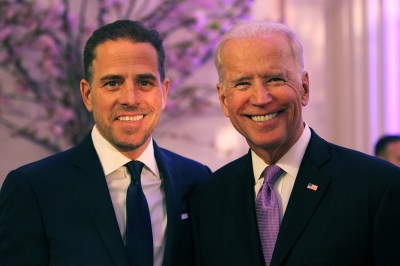

I don’t know much about Hunter Biden. I know a little about the people around him and his circle. I know that his father is a callous, vicious, dishonest man who would make a great deal of political hay out of it if the man in the dock had been, say, Donald Trump Jr. (And, who knows, maybe it will be, someday.) And I have no doubt that Joe Biden would enjoy such an opportunity for cruelty, in his obscene way. It isn’t that the Trumps don’t have it coming—but our pews are full of people who have vowed to give people better than they deserve, knowing what they themselves ultimately deserve. Some of them may even have once meant what they said about forgiving others that they might themselves be forgiven.

One of the newspapers I used to edit covered the basketball player Allen Iverson from time to time. He was a troubled guy, and still is. My read on Iverson is that, while I didn’t grow up with a lot of social capital, I grew up with a good deal more than he did. And if you’d given me the kind of money and fame that landed on him when he was a young man—a young man fresh out of prison—I don’t think I’d have turned out as well as Iverson did. It probably would have killed me. I haven’t had exactly the kinds of problems that Hunter Biden has, but I’ve had problems in roughly the same ZIP code. I haven’t engaged in the kind of grotesque influence-peddling that the Bidens have, but, then, I haven’t had the opportunity to, either: I don’t have much influence to peddle or a surname that you can wring money out of. I make a decent living, but I don’t have the kind of money that you have to have to buy the kind of trouble that Hunter Biden has bought for himself.

One of the problems endured by the friends and family of drunks, drug addicts, and mentally ill people is that some of these people are just jerks on top of their substance abuse and psychiatric problems. As it turns out, some people are suffering from an addiction or other mental health problem that demands our aid and sympathy and are simultaneously insufferable asshats. It can be hard to untangle the strands of an exasperating personality, and, more often than not, it isn’t worth the effort. The smart man walks away when he can. But you can’t walk away from your children, even if you are the kind of rotten man that Joe Biden is.

Not a lot of people end up doing time for what Hunter Biden has done. But who knows? A little bit of jail might do him some good. I’ve seen people I cared about drink and snort themselves to death. I’ve seen people I didn’t care about drink and snort themselves to death, too. There isn’t anything about Hunter Biden that makes me think he represents Our Lord’s very best work, but that isn’t a judgment I am called upon to make. (I am sure the Creator of the universe appreciates my forbearance.) I hope Hunter Biden gets his act together, and if that requires a divine touch, then I suppose everything good ultimately does.

A better sort of man would pray for Hunter Biden because there was some fine thing in him that moved him to do it. I’ll say a prayer for him because I am supposed to. There’s something to be said for going through the motions when you really consider the alternative.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.