Dear Captiolistae,

Seemingly everywhere you turn these days, someone is expressing doubts about “globalization” and lamenting its impact on American workers. This obviously has been a theme of the Trump administration and its America First approach to U.S. trade and immigration policy, but you may be surprised to learn that a lot of Biden folks have been saying similar stuff in recent years (see, e.g., this recent Wall Street Journal piece). And, unsurprisingly, the media—always on the lookout for a sympathetic victim of capitalist greed—has been similarly focused on globalization’s alleged harms.

Indeed, when articles like the WSJ piece above are written or political speeches are made, the sources usually couch any benefits of globalization—assuming they speak of them at all—in terms of consumers (the proverbial “cheap T-shirt” made abroad) or corporations and their shareholders (insert evils of capitalism here). Few stop to consider the broader benefits that the relatively free movement of goods, services, labor, capital, and ideas across national borders confers upon each of us and the nation or world more broadly.

So that’s what we’ll do today, looking at perhaps the best recent example of such globalization benefits: the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines that we’ll hopefully soon have injected in our arms. As you’ll see, every part of the vaccines—from corporate leadership to investment to research and development to production and distribution—depends on “globalization” and would suffer from government attempts to block it.

The Companies and Their Leaders

BioNTech, a German company with an office in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was founded by Dr. Ugur Sahin and his wife, Dr. Özlem Türeci—both of Turkish descent. The former immigrated to Germany from Turkey with his parents when he was 4 (his father worked in a German auto plant); the latter was born in Germany to Turkish immigrants. In 2019, Dr. Sahin won the Iranian Mustafa Prize, which is awarded to Muslims in science and technology.

Pfizer, the New York-based multinational with offices around the world, is run by Albert Bourla, a native of Greece who began at the company’s Greek outpost in the early 1990s. Bourla worked across Europe before moving to Pfizer’s global headquarters in Manhattan and later becoming CEO. Other top Pfizer execs include Angela Hwang, a South Africa native; Mikael Dolsten, a Swede; and Rod MacKenzie and John Young, both from the U.K.. Oh, and Pfizer was started in New York by two German immigrants—Charles Pfizer and Charles Erhart—in 1849.

Boston-based Moderna’s co-founder and chairman is Noubar Afeyan, a two-time immigrant. Born to Armenian parents in Lebanon, he immigrated as a teenager to Canada and then moved to the United States after college to earn his Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Stéphane Bancel, Moderna’s CEO, also immigrated to America (from France) for grad school. The company’s other co-founder, Derrick Rossi, was born in Canada and is here on an H-1B visa. Moderna’s chief medical officer, Tal Zaks, is Israeli and also here on an employment-based visa. The chief digital and operational excellence officer is from France, and their chief technical operations and quality officer is from Spain. (Seriously, it’s like the UN over there.)

Finally, the Trump administration’s point man for the vaccine, Operation Warp Speed chief Moncef Slaoui, is a Moroccan-born Muslim immigrant from Belgium (and now a U.S. citizen) who was formerly at British multinational pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline, serving as chairman of its vaccines division and global head of R&D. (He was also on Moderna’s board of directors prior to joining OWS.)

The Investment

All three companies are also major beneficiaries of global capital markets. Moderna was a concept-stage company for Boston area biotech venture capital firm Flagship Pioneering, which “has a history of building innovative biotech companies in-house,” according to Crunchbase News’ Joanna Glassner. It opened as a private company in 2012 with a $40 million VC jump-start, and then “raised over $2.7 billion in venture and growth funding, with backing from a mix of venture capital firms and corporate investors.” Moderna also received millions from the Gates Foundation in 2016 to develop therapeutics based on messenger RNA to treat HIV. It went public in December 2018.

Before the pandemic, BioNTech used various global private share listings to raise hundreds of millions of dollars and create the 1,800-person company. The company also benefited from its founders’ $1.4 billion sale of their previous company to Japan-based Astellas Pharma in 2016. Last year, the Gates Foundation invested $55 million to fund BioNTech’s work on HIV and tuberculosis, and the company went public. (Unsurprisingly, those shares have soared this year.)

Pfizer, of course, is a giant multinational corporation whose global revenues and investor base (a $224 billion market capitalization, as of Monday) allowed it to single-handedly fund, at a cost of about $2 billion, the BioNTech vaccine’s testing, manufacturing and distribution—without significant government assistance, by the way—and zoom past Moderna for the lead in the COVID-19 vaccine race. For example, “both Pfizer and Moderna were facing the problem of too few minority volunteers, but Pfizer had the deep pockets to solve it. The firm expanded its trial from 30,000 to 44,000, a decision... estimated cost the firm hundreds of millions of dollars.” As Pfizer CEO Bourla explained of the company’s $2 billion risk, “if it fails, it goes to our pocket. And at the end of the day, it’s only money. That will not break the company.” Must be nice.

The Research and Development

The vaccines’ research and development unsurprisingly followed the medical field’s longstanding model of global collaboration. For example, though Moderna’s researchers famously needed only two days to design their vaccine, they relied on a genetic map of the virus that was created by Chinese researcher Yong-Zhen Zhang and his team, including Australian Eddie Holmes. That map was released to the world on January 10 in an open-source depository and notified to the world via a single Holmes tweet on January 11. As chronicled by Zeynep Tufecki, these actions “sent shockwaves through the global scientific community” and were quite heroic: “the sequence was published ten days before China acknowledged the severity of the problem… [and] while China—and the WHO, which depended on China for information—were still downplaying what was going on, in their official statements.”

Meanwhile, yet another immigrant, Hungarian-born Katalin Karikó, was responsible for the messenger RNA (“mRNA”) technology behind both the Moderna and BioNTech vaccines:

After a decade of research at two U.S. universities, including with Drew Weissman, her “longtime collaborator at Penn,” Karikó solved the problem plaguing mRNA, namely that the body fought the new chemical after an injection. “Karikó and Weissman [created] . . . a hybrid mRNA that could sneak its way into cells without alerting the body’s defenses,” writes Garde. “And even though the studies by Karikó and Weissman went unnoticed by some, they caught the attention of two key scientists—one in the United States, another abroad—who would later help found Moderna [Rossi] and Pfizer’s future partner, BioNTech.”

Karikó today lives and works in the United States as BioNTech’s senior vice president.

Speaking of, BioNTech first partnered with Pfizer in 2018 on developing a flu vaccine using the mRNA technology, and that spawned their COVID-19 collaboration and the CEOs’ unlikely friendship (emphasis mine):

After BioNTech had identified several promising vaccine candidates, Dr. Sahin concluded that the company would need help to rapidly test them, win approval from regulators and bring the best candidate to market. BioNTech and Pfizer had been working together on a flu vaccine since 2018, and in March, they agreed to collaborate on a coronavirus vaccine.

Since then, Dr. Sahin, who is Turkish, has developed a friendship with Albert Bourla, the Greek chief executive of Pfizer. The pair said in recent interviews that they had bonded over their shared backgrounds as scientists and immigrants.

“We realized that he is from Greece, and that I’m from Turkey,” Dr. Sahin said, without mentioning their native countries’ long-running antagonism. “It was very personal from the very beginning.”

Gotta love it.

The Production

Production of the vaccines will utilize global supply chains and multinational manufacturing capacity that was both created for COVID-19 and already in place. Pfizer, for example, has numerous U.S.-based manufacturing, supply, and distribution sites, and chose three American facilities for the COVID vaccine: St. Louis, Missouri; Andover, Massachusetts; and Kalamazoo, Michigan. Those will be supplemented by Pfizer’s factory in Puurs in Belgium, which will serve Europe and will supplement the Kalamazoo plant. BioNTech also has substantial mRNA manufacturing capacity in Germany and received a German government grant to expand that production. The companies project that their combined manufacturing network will be able to supply about 50 million vaccine doses in 2020 and up to 1.3 billion doses by the end of 2021.

Pfizer’s factories will get raw materials from both the United States and Europe—part of a complex supply chain that Pfizer has established for production and delivery of the vaccine. The Financial Timesreports that the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine will be encapsulated in “lipid nanoparticles”—tiny droplets that “enclose and protect the fragile genetic instructions as they are manufactured, transported and finally injected into people”—sourced from Acuitas, a specialistCanadian company. (Britain’s Croda International may also supply Pfizer with lipids from a site it recently acquired in Alabama.) Pfizer has also reportedly contracted with Switzerland’s Siegfried for large-scale filling and packaging in Hameln, Germany.

While most of Pfizer’s and BioNTech’s production is in-house, Moderna will outsource most of its manufacturing to Swiss pharmaceutical manufacturer Lonza, which “is building out capacity for 400M doses a year—300M from three production lines in Visp, Switzerland, and 100M in New Hampshire…” and could add even more capacity in Switzerland next year. German firm CordenPharma will supply Moderna’s lipids from three European facilities and its largest one in Boulder, Colorado. Moderna also has contracted with New Jersey-based Catalent and Spain’s Laboratorios Farmacéuticos Rovi to provide vial filling and packaging support.

The Distribution

Finally, the vaccines will utilize a massive “cold chain” distribution network to deliver doses around the world. Pfizer piggybacked off its previous experience with global refrigerated distribution and set up cold storage systems in the United States and Germany, including the creation of suitcase-sized “cool boxes,” to transport the vaccine. Pfizer also partnered with cargo companies (FedEx, UPS and DHL) and United Airlines (which would fly between Brussels and Chicago) to deliver the vaccine. Other U.S. and foreign commercial airlines, which have spare capacity due to COVID travel restrictions and depressed demand, are also getting involved. The International Air Transport Association “estimates that the equivalent of 8,000 loads in a 110-ton capacity Boeing 747 freighter will be needed for the airlift, which will take two years to supply some 14 billion doses, or almost two for every man, woman and child on Earth.”

The U.S. government took a different approach and selected Texas-based global medical goods wholesaler McKesson Corp. to distribute other COVID-19 vaccines, including Moderna’s doses, through Operation Warp Speed. With offices throughout North America, as well as in Australia, Ireland, France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, McKesson has decades of experience delivering drugs around the world.

Global cargo companies’ recent efforts to prepare for the vaccines are impressive:

“UPS is lining up rows of freezer units, packed together in what the company calls freezer farms, for vaccines requiring minus 80 degrees Celsius in Louisville, Ky., and Venlo in the Netherlands, near the delivery giant’s global air hubs”;

“Lufthansa Cargo, the freight arm of Deutsche Lufthansa AG, sped up construction of two pharmaceutical storage facilities, at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport and Munich Airport, in part to be ready for a vaccine”; and

“DHL Global Forwarding is evaluating plans to transport vaccines through a combination of air and expedited ocean shipping, which the company has used to deliver personal protective equipment…”

“KLM workers are gearing up for a surge next year in COVID-19 vaccine cargos that will need to be flown around the world at ultra-low temperatures. A major hub for pharmaceutical products, Schiphol [Netherlands]* has already handled some of the vaccines being used in trials and KLM's boss is confident its ‘cold chain’ operations will cope with the influx of cargos as mass inoculations start in earnest.”

All of these efforts, however, rely in large part on the massive and mind-numbingly complex global shipping, storage, and logistics systems and capacity already in place due to global trade. (And don’t even get me started on how the jets are made.) As logistics expert Brian Bourke told the Wall Street Journal, global vaccine distribution will be “the equivalent of every iPhone, Galaxy and PlayStation launch all at the same time.” If we didn’t already have the networks and technology that invisibly developed over decades to deliver those (and other) goods, shipping the COVID vaccines at the projected speed and scale would have been impossible.

Summing It All Up

Last week, Vice President Pence credited the COVID-19 vaccine rollout in the United States to President Trump’s leadership and Operation Warp Speed, telling his audience that only in America “could you see the kind of innovation that's resulted in the development of a vaccine in record time."

Surely, some U.S. government vaccine efforts, for example regulatory relief or advance purchase agreements, warrant praise, and there are plenty of Americans and American institutions involved. But the sections above show that the BioNTech/Pfizer and Moderna vaccines rely less on a handful of government officials or any one nation than on the global flow of knowledge, capital, people, and goods—as well as the dense distribution networks and free market policies facilitating those movements—that existed long before we’d ever heard of COVID-19. Even this “globalization,” however, really just scratches the surface. I didn’t mention, for example, the multinational testing and research teams, or the other vaccines being produced by similar collaborations (some of which I documented in a recent blog post). Nor did I detail all of the little things—like glass vials, “adjuvants,” and dry ice (or the machines that make or transport these items)—that we often ignore but without which the speedy development and distribution of the COVID-19 vaccines wouldn’t be possible.

Documenting all of these benefits would take a book, not a newsletter (if it were even possible at all). But we can start by at least recognizing that they—and the organic processes by which they’re developed—exist, instead of pretending that “globalization” is all about cheap t-shirts and corporate greed.

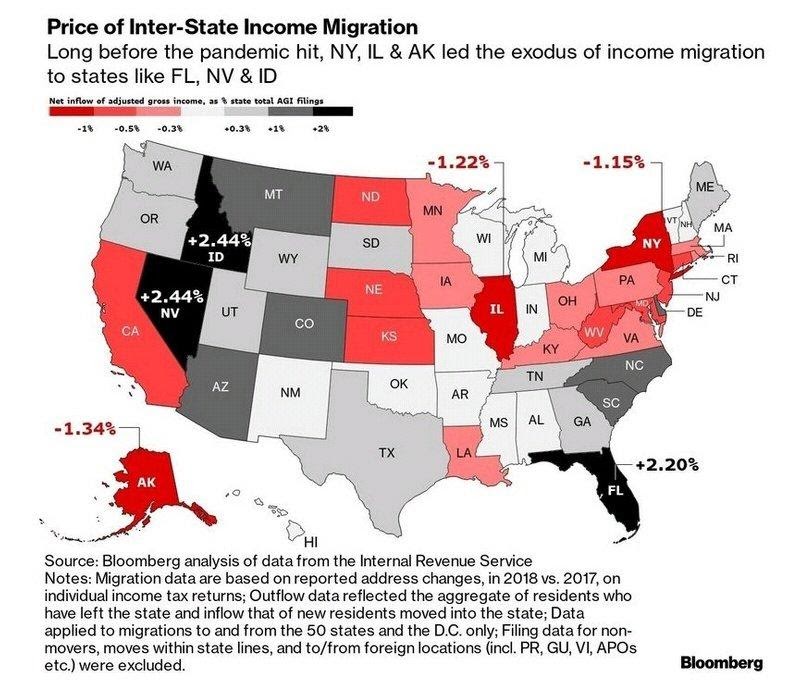

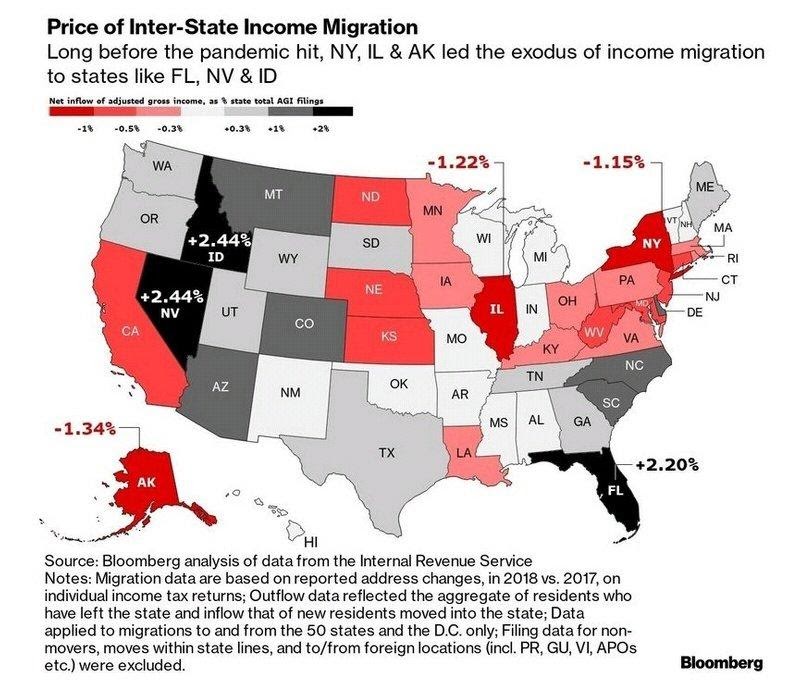

Chart(s) of the Week

The “Expensive Exodus” was well-underway before COVID (source):

The Links

*Correction, December 9: This piece initially stated that the Schiphol airport is in Sweden. It’s in the Netherlands.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.