Given the (ahem) tumultuous U.S. trade and economic situation and various personal obligations, I’ve been doing a lot of air travel this summer—a lot. While these trips have been physically and mentally taxing, they came with a silver lining: They’ve allowed me to conduct an informal field test of the effects of the July 8 change to the Transportation Security Administration requirement that most U.S. air travelers remove their shoes when transiting through airport security checkpoints nationwide. As anyone who has flown in the last two decades can attest, the simple “shoe rule” is highly annoying, but did it have a meaningful effect on wait times at airport security? The TSA seems to think so, with DHS Secretary Kristi Noem stating on the day of the announcement that the agency expects the rule change to “drastically decrease passenger wait times at our TSA checkpoints.”

And you know what? She’s probably right.

My initial findings—informally measured using the same airport pair (Raleigh-Durham to Reagan National) over several trips immediately before and after the rule change—showed a substantial and noticeable reduction in standard security wait times at both airports. Not a couple minutes but 15 or more, at least. It was a great and remarkable shift, and one that will have me changing my standard buffer for arriving at an airport to ensure I make my flight. And I’m certainly not alone in noticing the change.

But my experiment also has me wondering: How much of our lives did the old rule needlessly waste—and how many other rules are out there today doing the same?

As a non-paying reader, you are receiving a truncated version of Capitolism. You can read Scott's full newsletter by becoming a member here.

The TSA Shoe Rule: Arguably the Worst of ‘Security Theater’

Before you ask, yes, the TSA shoe rule was needless. As Reason’s Jacob Sullum just detailed, the rule was implemented in 2006—five years after infamous (and clueless) “shoe bomber” Richard Reid first boarded an American Airlines international flight and then tried to ignite explosives in his sneakers (some urgency!). Even back then, the rule made little sense: A week before TSA adopted it, the agency was still advising people that shoe removal was unnecessary, and terrorism experts questioned whether a “shoe bomb” could actually avoid detection and take down a plane. “If you search people's shoes,” security expert and TSA critic Bruce Schneier told Newsweek last month, “they'll just put the bomb somewhere else, like in another piece of clothing."

The initial skepticism of the rule has only grown over time. In 2011, for example, aviation security experts doubted that the rule was necessary or effective in deterring terrorism, and then-Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano promised the rule would be eliminated “in the months and years ahead.” Most damningly, almost no other places adopted the shoe rule—including common terror targets like Israel (which spends much more on airport security overall). Another clear indication of the rule's pointlessness: It was nixed last month without any new shoe-safety technologies having been widely deployed.

As Massachusetts Institute of Technology security expert Yossi Sheffi admitted back in 2011, “this seems to be a make-everybody-feel-good thing rather than a necessity." It’s thus a classic case of “security theater”: onerous and/or annoying government rules and procedures that are originally imposed to assuage public fear of criminal activity but do little or nothing to actually reduce it.

Yet it took 19 years for the government to reverse course.

And It Cost Us Billions

In isolation, losing a few minutes of your life to comply with this useless regulation may seem meaningless. But those minutes add up, and collectively they mean a massive hit to Americans’ time and money. Consider the following stats and back-of-napkin calculations:

- According to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, more than 1.1 billion people—852 million domestic and 255 million international—used U.S. airports for air travel in 2024 alone. Only 20 million of these people had TSA PreCheck, which would allow them to keep their shoes on when transiting through security, but they’re more frequent travelers. If we assume they take seven or eight trips per year—most business travelers take seven—and throw in the small number of oldsters and kids exempt from the rule, we get around 900 million shoe-removing trips per year. (Dad note: My daughter still often took her shoes off because everyone else was and because she’s a better citizen than her grumpy father.)

- Given the time it takes for each person in the regular security line to comply with the shoe rule and for TSA to enforce the rule (e.g., requiring forgetful people to remove their shoes), and given that PreCheck saves an average of 7 minutes through security, we can reasonably (and very conservatively) assume the TSA rule change has cut an average of 5-10 minutes off every traveler’s total security screening wait time. (That’s actually well below my own experience, but maybe other airports are different.) If it’s right, the total annual time savings gained by eliminating the shoe rule would fall somewhere between 4.5 billion and 9 billion minutes last year alone. Put another way (since we’re all innumerate), the TSA rule needlessly took 8,561 to 17,123 years off our collective lives in 2024!

- The numbers are even more mind-boggling over the life of the TSA shoe requirement: BTS reports that U.S. airports have serviced almost 16.4 billion travelers since the rule began in 2006—an average of 861 million per year. Using the same 5-10 minute cost assumption, that means the TSA rule could have cost U.S. air travelers from 81.8 billion to 163.6 billion minutes (aka 155,628 to 311,255 years!) over the program’s lifetime. Even if you limit it to 2011, when the U.S. government first said it would nix the rule, you’re talking a total time suck of between 61.8 billion and 123.5 billion minutes. Shave off a little for exempt travelers, and you’re still talking a massive amount of time lost for a dumb rule that should never have existed—and didn’t exist most everywhere else.

This wasted time, as we’ve discussed, has economic value because it represents time not spent doing more important or productive things than standing in line at the airport (i.e., literally anything). Maybe instead of getting to the airport a little earlier—itself a questionable time suck—we instead stay at work or hang out with family a little longer or do any number of things that we value or that generate real income. Calculating the shoe rule’s exact “opportunity cost” is difficult (and well above Capitolism’s pay grade), but we can at least throw out some ballpark figures for reference:

- At the end of last year, American workers earned an average of $47.20 in hourly compensation. If TSA’s shoe rule cost us around 112.5 million hours (halfway between the 2024 estimate above), it’d equate to almost $5.3 billion in 2024 alone.

- Leisure time, meanwhile, has roughly been valued at around $30 per hour, meaning an annual economic loss of “only” $3.4 billion.

- Using these benchmarks, we can conservatively estimate that the shoe requirement easily imposed tens of billions of dollars in economic costs over the 19 years it was pointlessly in place. (Averaging the two numbers above, the $83 billion loss would be larger than the annual economic output of seven different U.S. states.) That’s more than a little annoying.

These figures are obviously just some napkin math, but we can be pretty confident they’re directionally correct because 20 million people are willing to pay $78 a year to skip the security-line hassles and many are now openly reconsidering that expense because the shoe rule was nixed. The dollar figures above could also easily be higher. Beyond the actual amount of time lost, for example, air travelers’ incomes likely skew higher than average. Throw in possible missed flights and other delay-related costs, and the shoe rule could cost much, much more than the already-crazy figure I noodled above.

Even worse, we’d been doing it for almost two decades.

Lessons Abound

And that gets to the first lesson the TSA shoe rule hopefully teaches us: Once a government rule is in place, it is exceedingly difficult to remove it—even when it’s costly, unpopular, and unnecessary. As Rachel Augustine Potter documented years ago for the Brookings Institution (hardly a bunch of anti-government zealots), anyone seeking to remove a regulation—good ones or bad—will encounter numerous “institutional factors” that are sure to slow things down, if not stop them entirely. “Federal agencies,” she notes, “must go through the same laborious notice and comment process to undo existing regulations” as the one followed to establish them—a legal minefield that “could take many, many years” to navigate. The bureaucrats needed to carry out the deregulation, meanwhile, could slow-walk or otherwise impede its implementation—especially when doing so would serve their own professional or political interests. The courts could further stymie reform, and Congress—depending on its partisan makeup and public polling on the issue—might also try to intervene.

These institutional hurdles, as well as simple public disinterest, help to explain how it took almost a century to eliminate U.S. tea-tasting regulations and the four-person, $500,000/year federal Board of Tea Experts—and another 27 years(!) for the FDA to officially scrap the system in 2023. As the Competitive Enterprise Institute’s Ryan Young noted at the time, “There are many other US federal entities that are either dormant or useless.” And yet they’re still just hanging around—at taxpayers’ expense.

Non-governmental factors can further imperil reform. As we’ve often discussed, new government policies—taxes, subsidies, prohibitions, fees, requirements, whatever—inevitably create new private constituencies that disproportionately benefit from the rules and will lobby hard against their removal. Additional complexity alone does the same. Rules related to the environment, health, and safety are especially difficult to change, as doing so is sure to arouse public opposition and partisan opportunism—and thus to discourage notoriously risk-averse bureaucrats and political appointees from rocking the regulatory boat. As Reason’s Sullum explained regarding the shoe rule:

The longevity of that widely resented and ridiculed policy, which the U.S. was nearly alone in enforcing, illustrates the ratchet effect at work in security theater: Even the most dubious safeguards tend to stick around because eliminating them looks like a compromise that might endanger public safety.

This problem—along with the cronyism, of course—also explains why reforming other regulations supposedly “protecting” us, such as occupational licensing rules, is similarly difficult. And it’s why the FDA takes so darn long to do simple things like let us buy cheap medical tests or effective sunscreen. Even when we know these rules are bogus and enrich a select few at a big public cost, eliminating them is a steep uphill climb—one that must be done for each of the hundreds (thousands?) of dumb rules in place.

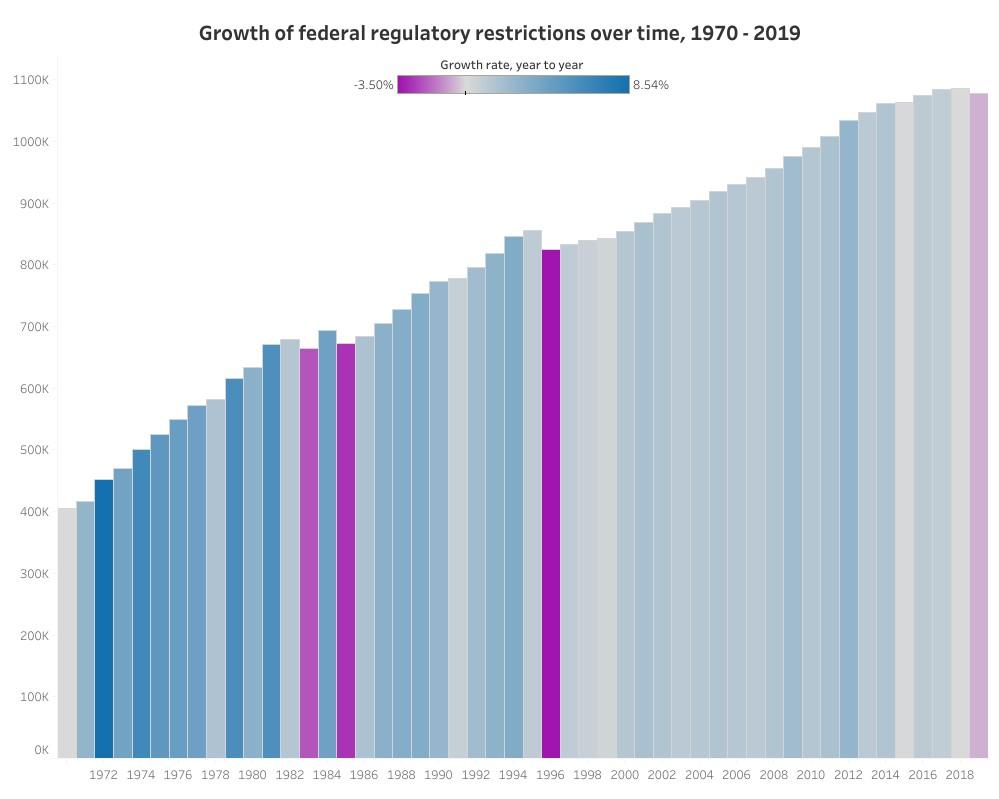

Put it all together, and it’s no surprise that our regulatory morass really never shrinks—even when controlled by U.S. presidents who campaigned on that very thing.

The TSA shoe rule is also an important lesson in how seemingly small bureaucratic hurdles can quickly compound to impose large costs on individuals and the U.S. economy. And it raises the depressing question of just how much of our lives (and how much money!) is being wasted on stuff like needless, annoying paperwork and procedures that exist just because they do or because legislators and bureaucrats are too lazy, scared, or indifferent to change them. This includes not just airport “security theater” nonsense—don’t even get me started on the TSA’s insane peanut butter rule—and the billions we waste annually on tax compliance, but plenty of other federal, state, and local hurdles that we barely notice in isolation but matter a ton in the aggregate. Just this week, in fact, I spent 10 extra minutes at the drug store waiting to get carded so I could buy “controlled” cold medicine (because, as we’ve known since 2007, the over-the-counter alternative literally doesn’t work).

None of this means we should have no regulation, but it should at the very least make us more skeptical of new government rules—especially ones implemented after a highly publicized emergency or security breach. And we should demand bigger and better safeguards on their implementation—things like independent and transparent cost-benefit analyses before a rule’s enactment and its mandatory termination (sunsetting) after a few years, absent thorough review and express reauthorization. Those commonsense reforms certainly won’t stop all bad rules from happening, but they’d probably save us a few minutes at the airport, drugstore, DMV, and other common, annoying destinations.

And as the shoe rule shows, that can really add up.

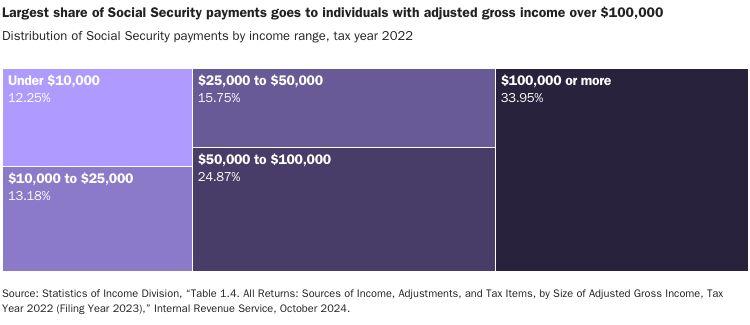

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.