Dear Capitolisters,

Though my youthful visage and impish charm might depict a much younger man (lol), I actually got my policy start in the late 1990s. Back then, “globalization” was for many a dirty word—a destructive, corporatist force facing widespread protests, most famously at the 1999 World Trade Organization meetings in Seattle. For a while, it seemed those days were over, but the last few years have witnessed renewed criticism from the left and right—in the United States and abroad—on the relatively free movement of things, people, capital, and ideas across national borders (aka “globalization”).

Today’s critics put a modern spin on the old anti-globalization arguments, but they too err on both the facts and the fundamentals. Unfortunately, those arguments have regained some prominence in the media and (especially) in Washington. Perhaps even more unfortunately, they’ve also won some converts among wonks, pundits, and politicians who—up until very recently—championed free markets and free people here and abroad.

So, with this in mind, we at Cato are launching today a big new project, Defending Globalization, aimed at both correcting the record on globalization—what it is, what it’s produced, what its real alternatives are, and what people think about it—and offering a strong, proactive case for more global integration in the years ahead. It’s a big endeavor that’s been occupying a lot of my time, so I’m gonna exercise the ol’ newsletterer’s prerogative and tell you all about it.

Before we get to that, however, let’s recap how we got here.

The Modern Anti-Globalization Movement: Clear, Simple, and Wrong

I first conceived Defending Globalization late last year after reading yet another mainstream piece lamenting cross-border trade and migration—and just butchering some basic facts in the process. In the all-too-common retelling of recent history, quasi‐religious devotion to “market fundamentalism” among “global elites” singlehandedly drove decades of unfettered and ever‐increasing global integration, basically as if guys like Milton Friedman and Larry Summers cooked up “globalization” in a 1990s lab somewhere—probably Davos—and then unleashed it upon the helpless and unwitting “working class” masses here and abroad.

Even worse, these misguided (nefarious?) “globalists” utterly failed to achieve the mass prosperity, peace, and democratization that they predicted, delivering instead poverty, joblessness, “deindustrialization,” economic fragility, geopolitical insecurity, and (probably) sad puppies—all while hollowing out the global middle class, destroying our communities, and fueling the now‐unstoppable rise of authoritarian regimes. Some folks have gone even further, claiming that globalization is primarily responsible for recent events—the rise of global populism and authoritarianism, the COVID-19 pandemic, marked changes in China’s economic and geopolitical trajectory, and so on—and now that we’re all finally waking up to this supposed reality, the backlash will usher in the “death of globalization” and the return of localized economic activity (and, presumably, happier puppies).

In short, critics of globalization argue that we were promised the “end of history” but instead got empty store shelves, authoritarian invasions, and Donald Trump (and other populists)—problems that critics say only more protectionism, nativism, industrial policy, and even “deglobalization” can fix.

This anti‐globalization narrative is clear and simple. But, as the famous Mencken saying goes, it’s also mostly wrong—typically taking a nugget of truth and then wildly extrapolating a goldmine underneath. We’ve discussed a lot of this here at Capitolism over the years, but let’s quickly tick through some of the most prominent examples:

- Tariffs have surely declined around the world since the 1940s, but we hardly live in an age of “unfettered” trade, migration, and capital flows—as anyone even passingly familiar with the Jones Act, the anti-dumping law, U.S. green card obstacles, and sanctions can attest. Indeed, despite past policy liberalization, the United States maintains high tariffs or non-tariff restrictions on lots of goods (trucks, shoes, sugar, and dairy products, for example), subsidies to plenty of favored industries, a relatively low foreign-born share of its population, and high restrictions on trade in many services—whether performed here or transmitted digitally from abroad. When you consider these barriers collectively, the United States goes from “free market fundamentalist” to “yet another country that has a mix of liberalization and nationalist interventions,” and the U.S. economy isn’t nearly as “globalized” as Americans think.

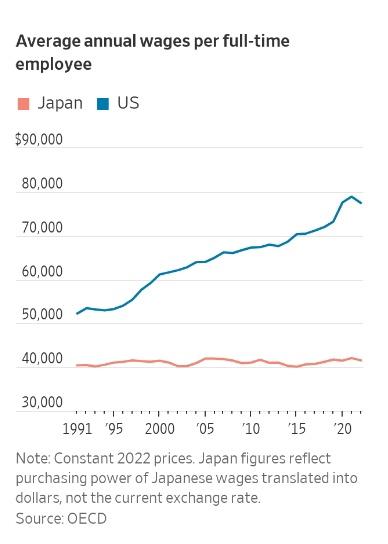

- Manufacturing jobs have fallen a lot from their historic highs, but they’ve followed a similar long-term path in almost every industrialized nation in the world—including ones with active industrial and labor policies and persistent trade surpluses—and have steadily occurred despite myriad U.S. government efforts to reverse the trend. (We’ve actually gained more than 1 million manufacturing jobs since the Great Recession but remain a long way from the “mill town days” of decades past.) Meanwhile, U.S. industrial output still ranks second in the world overall (No. 1 in several major industries and among major manufacturing nations in terms of output-per-worker) and hovers at or near record levels.

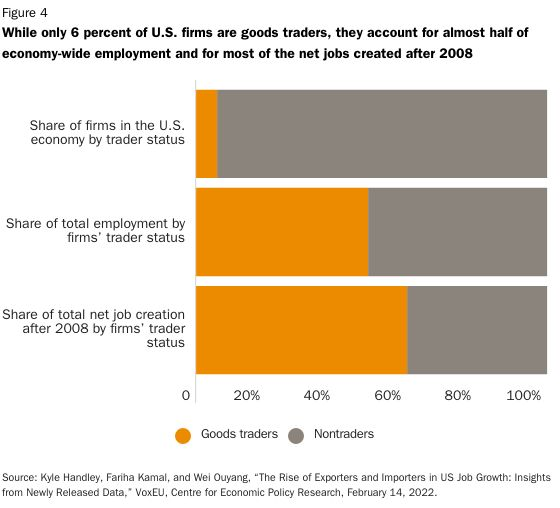

- New foreign competition (imports, immigrants, etc.) surely has disrupted certain companies and workers that were once protected by government trade and immigration restrictions. But these same forces—yes, including those involving China—have also boosted living standards, fostered innovation, and supported tens of millions of good jobs, including in manufacturing. And their indirect harms, while surely real, have been greatly outweighed by other, bigger economic and cultural factors. In recent years, fewer than 10 percent of non-working, prime‐age Americans report being out of work because they can’t find a job.

- Some older industrial cities do indeed remain depressed following decades of trade liberalization, but it’s hard to blame trade for that when far more of them—towns like Pittsburgh; Greenville, South Carolina; and many others—have moved on, diversified, and are today thriving. Indeed, one of the poster-child towns for the “China Shock’s” destruction—Hickory, North Carolina—was recently ranked (in two different publications!) among the best small towns to live in the country, and its legacy furniture manufacturers struggle to find people to work in the mills (and hold job fairs when a local competitor announces layoffs).

- Economic “interdependence” can raise resiliency and security issues when global or overseas shocks occur, but it also mitigates domestic shocks, discourages armed conflict, and speeds adjustment (hence why global supply chains proved more resilient than local ones). We’ve already discussed—repeatedly—the insane fragility (and entrenched politics) of U.S. baby formula autarky, but see this project essay for more on the geopolitics. Or just consider … Girl Scout cookies:

- Globalization does mean more travel and container ships and production and other things that can harm the environment. But the wealth it produces also can lead to greener places once countries hit a certain level of development.

At the same time, things we often think are dirtier—like that classic cup of pears shipped around the world to arrive in Western lunch boxes—are actually more environmentally friendly, thanks to “globalist” things like comparative advantage, specialization, and economies of scale.

- And the world has surely witnessed a resurgent illiberalism in recent years, but globalization is (or was?) at most only one of this trend’s drivers (including in the United States) and at least only an excuse for what are actually cultural, noneconomic motivations. Meanwhile, both the retreat of liberalism and the broken link between economic and political freedom have been greatly exaggerated.

I could go on, but you (hopefully) get the idea. (Indeed, we’ll need to soon devote a whole column to the conventional wisdom’s sudden and humorous about-face on China’s supposedly unstoppable state capitalism. Welcome to the party, pals.)

But It’s Not Just Factual Errors and Quarter-Truths

Our new project will eventually have essays covering all of these issues—and many more. But critics of globalization don’t just get their facts wrong (though they do that a lot, too). They fail to grasp several fundamental, undeniable truths about trade, migration, and life in the 21st century.

First, government (or “elite”) action—tariffs, trade agreements, capital controls, visas, etc.—is only part of globalization’s story, several chapters of which were written thanks to new technologies like the shipping container or before today’s governments and political borders even existed. As Adam Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations, “Man is an animal that bargains,” as we humans are unique among the world’s creatures in our ability to peacefully exchange goods and services to meet our needs and improve our lives. Indeed, as we discussed in my review of Superabundance, perhaps the most important ingredient in the “special sauce” that is centuries of modern human flourishing is the relatively free exchange of stuff and ideas that humans have been doing—or trying to do, if states would let them—for millennia, and with little regard for race, religion, class, or nationality.

So, “globalization” is foremost a story not of soulless multinational corporations, globalist elites, hollow statistics, or faceless political regimes, but instead of individuals and of humanity itself.

It’s the story of how Mazhar Hussain helped turn the iconic Philly cheesesteak into a wildly popular dish in Lahore, Pakistan:

Pakistan’s fast-food boom of the 1990s and 2000s overlapped with a rise in Pakistanis traveling to the U.S. for study, work, business and immigration. As a result, many of the food establishments launched in Pakistan at the turn of the millennium were brimming with ideas that those visiting the U.S. brought back with them. The cheesesteak was one of these. … Even today, online food groups in Pakistan are peppered with people asking the community where they can find a cheesesteak in Lahore “like the one at Pat’s.”

Mazhar’s version blends the original Philly flavors with traditional ones from Lahore, which itself “blends Persian and Afghan flavors.”

And if that sandwich sounds great to you but you don’t feel like flying to Lahore, don’t worry: you can also find it (and other cool cheesesteak spinoffs) in Philadelphia today. Yum.

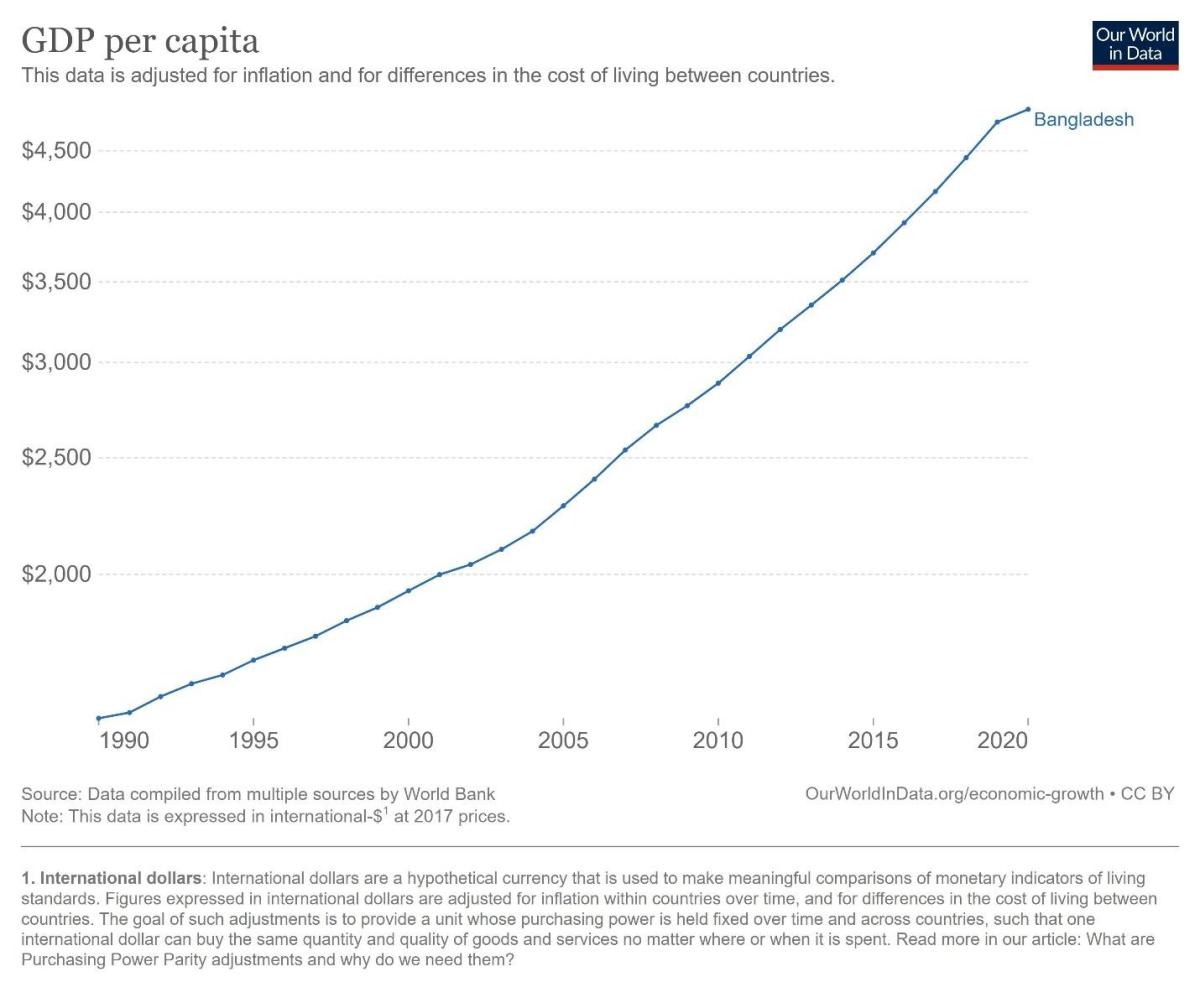

Globalization is also the story of people like sisters Shumi and Minu who escaped a rough upbringing in rural Bangladesh by making T-shirts in downtown Chittagong at what many in the United States derisively call a “sweatshop”:

In the past decade, millions of Bangladeshis have started working in the garment industry. Many of them are like Shumi and Minu: They grew up in villages where conditions are even worse than they are for factory workers in the city. When Shumi and Minu were growing up, sometimes there wasn't enough food to eat. They had three younger sisters who all died before they were 7. Now, Shumi and Minu are able to send money home. It isn't much, but it makes a big difference in the village.

"Now, we can eat whatever we want," their mother says. Their parents have built a new house, made of brick, to replace their old, bamboo house. And their younger brother can stay in school.

Bangladesh today surely isn’t rich, but it’s a heckuva lot better off than it was before global apparel trade got there—especially for young women like Shumi, Minu, and many others.

The globalization success stories aren’t just in developing countries, either. Consider, for example, this recent Wall Street Journal piece on how Chris Koerner in Dallas hired a foreign Ph.D. mathematician (coincidentally also from Pakistan) to help his 12-year-old son learn algebra over the internet. Or this CNBC piece on how Clarissa Rankin from Charlotte supports her young family by independently hauling imported TVs and other goods across the country—and streaming her adventures on Chinese-owned TikTok. Or John Hall, who since 2004 has worked in the engine-assembly department at the Korean-owned Hyundai Motor Manufacturing plant in Alabama—a facility that, Hall told the Commerce Department a few years back, is vital to the local community and relies heavily on imports and exports of automotive goods.

You get the idea.

These and millions of other stories happen every day. They’re often messy and imperfect, and surely not all have happy endings. But the vast majority of these episodes quietly do end well with nary a “globalist elite” around, and their collective arc has been overwhelmingly positive—for them and humanity writ large. Yet, save the occasional media writeup about a Pakistani cheesesteak, you won’t hear a peep about these people, even though new tariffs, sanctions, and other policies can disrupt (or worse) the lives they’re peacefully and voluntarily living. (Here’s an indicative list.)

Bad news sells. “Man successfully engages in commerce” doesn’t.

Relatedly, today’s anti‐globalization champions revel in the disruption that more open trade and migration can produce, but they too often ignore the massive, hyperpolitical trainwreck that true “deglobalization” would inevitably require—like the Trump tariffs on steroids—and that the likeliest alternative to our modern, globalized world is a more fragmented and static system that has been repeatedly shown to have more conflict, less freedom, more inequality, and more poverty. They protest, for example, China’s rise and recent illiberalism, but ignore both the alternative scenario—e.g., a more isolated and desperate regime with more than 1 billion people, a massive army, and troves of nuclear weapons—and the hundreds of millions of Chinese people who are today (even under Xi Jinping) living exponentially better lives than their grandparents were before China opened to the world.

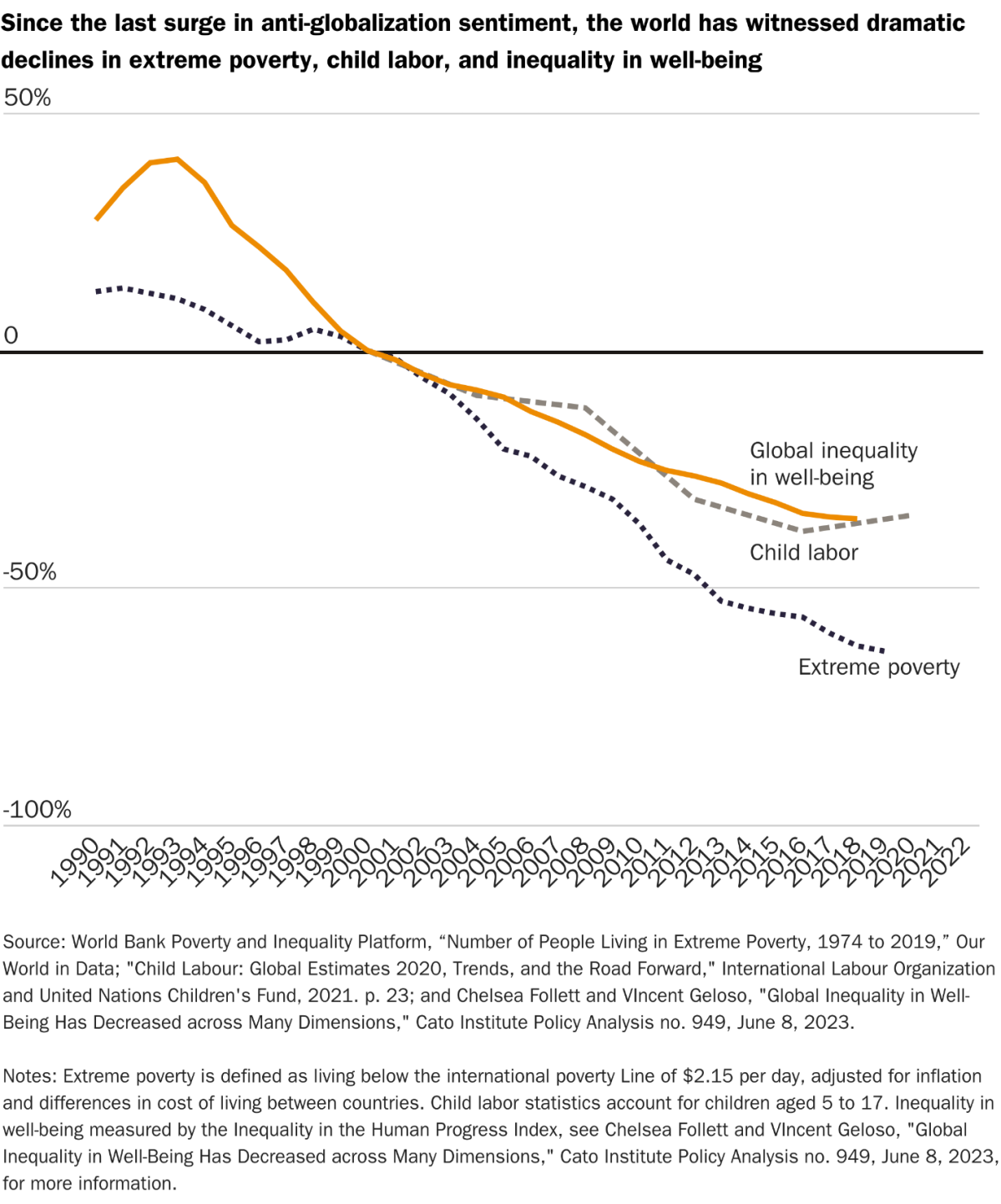

Indeed, since those famous 1999 anti‐globalization protests in Seattle, the world has seen more than 1 billion people—yes, billion with a B and no, not just in China—escape extreme poverty, thanks in no small part to what those protesters sought to dismantle. And we’ve enjoyed similarly breathtaking improvements in child labor, inequality, and other important metrics—all as U.S. wages, employment, and living standards have continued to rise.

Given these realities, it’s important not just to defend past globalization (despite the project’s title) but to seek more of it in the years ahead—especially in regions and sectors that remain relatively untouched by freer markets. We’ll be making this case with not only reams of data and scholarly research, but also with an understanding of the essential humanity of trade and migration that just so happens to cross political borders. And we’ll do it in several formats that we’ll roll out over the next year, including:

- An online library of accessible essays on a wide range of globalization issues—economics, foreign affairs, law and politics, history, and culture—written by me and several other Cato scholars (including Deirdre McCloskey and Johan Norberg) and by outside experts like George Mason economist Don Boudreaux, international relations expert Dan Drezner, Harvard’s Robert Barro and Rachel McCleary, Wall Street Journal film critic Kyle Smith, economic historian Phil Magness, former Congressman Jeb Hensarling, and others. The first eight are online now, and more will be regularly rolled out in the weeks ahead.

- An interactive quiz to test your knowledge of the myths and realities of globalization

- New polling on Americans’ actual views of globalization

- A big conference in D.C. and events around the country (Bono is invited but not yet confirmed)

- Videos and other media on both the facts and faces of globalization—real people who benefit greatly from our globalized world. (My video introducing the project is also online today.)

You’ll find these items and more at Cato’s new Defending Globalization webpage. I hope you find the message both educational and compelling.

And if you don’t want to take my libertarian (“fundamentalist”) word for the necessity of all this stuff, don’t worry: There are plenty of others who agree beyond those who have kindly agreed to participate in the project. In the famous NPR series documenting the lives of those Bangladeshi garment workers, for example, the narrator notes that the one thing on which “labor activists and factory owners” could agree is that the “worst possible thing” for those ladies and other garment workers “would be for the garment industry to leave Bangladesh altogether.”

One of my personal favorite quotes in this regard comes from U2’s Bono—someone who has spent decades working on global development and told the New York Times in 2022:

I ended up as an [antipoverty] activist in a very different place from where I started. I thought that if we just redistributed resources, then we could solve every problem. I now know that’s not true. There’s a funny moment when you realize that as an activist: The off‐ramp out of extreme poverty is, ugh, commerce, it’s entrepreneurial capitalism. I spend a lot of time in countries all over Africa, and they’re like, Eh, we wouldn’t mind a little more globalization actually.

Our current generation of globalization protesters would deny this wish.

Summing It All Up

Globalization, like any market phenomenon, is imperfect and often disruptive. But the relatively free movement of goods, services, people, capital, and ideas across natural or political borders has also produced immeasurable benefits—for the United States and the world—that no other system can match. In that same NYT interview, Bono added,

[Economist Thomas Piketty] has a system of progressive taxation and I get it, but the question that I’m compelled to answer is: How are things going for the bottom billion? Be careful to placard the poorest of the poor on politics when they are fighting for their lives. It’s very easy to become patronizing. Capitalism is a wild beast. We need to tame it. But globalization has brought more people out of poverty than any other -ism. If somebody comes to me with a better idea, I’ll sign up. I didn’t grow up to like the idea that we’ve made heroes out of businesspeople, but if you’re bringing jobs to a community and treating people well, then you are a hero. That’s where I’ve ended up.

Defending Globalization is a tribute to those heroes and others like them, and we at Cato are happy Bono’s here with us (in spirit, at least).

And as for that “better idea,” we’re confident he’ll never find it.

Thank you for reading and supporting The Dispatch. Today's Capitolism, normally for members only, has been unlocked for all to read. If you value the work we're doing you can help us grow simply by forwarding this email to anyone you think would appreciate our work. They can sign up for Capitolism and a Dispatch account from the link at the top of this email.

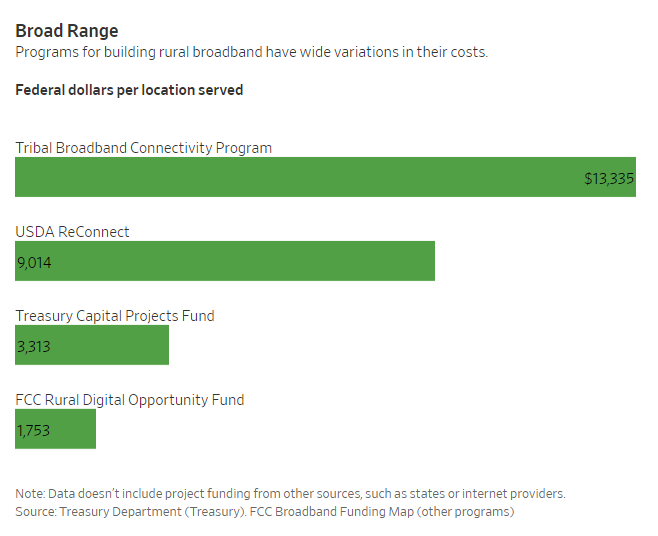

Chart of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.