Hi,

In this “news”letter of all places, I don’t think I should be required to demonstrate that I have a soft spot for weirdness, eccentricity, and unconventional ideas—and neither does the life-sized replica of Tito Puente landing on the moon I’ve made out of marzipan and luncheon meats that I spend most of my day talking to in Esperanto. (Ĉu ne ĝuste, Tito?)

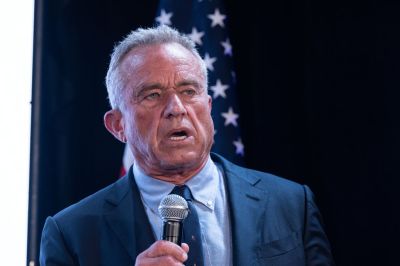

I bring this up in part because, much like Robert F. Kennedy Jr., I too have creatures eating my brain. At least I think that’s what’s going on up there. They make a slight rustling sound, and I don’t mean like cattle-rustling with the hootin’ and hollerin’ as they ride up on my medulla oblongata. I mean like the soft susurrating sounds of very specific cranial termites devouring every trace of anyone named “Todd” from your long-term memory.

More to the point, when normal Americans said they wanted an alternative to choosing between a doddering and indecisive incumbent president and a decadent and deceitful one with a fondness for despots, what they didn’t have in mind was a loony conspiracy theorist recovering from a bad—and not entirely metaphorical—case of brain worms.

Look, like RFK Jr. showing you an X-ray of a trilobite, I want to be transparent about what’s on my mind. I didn’t start out planning to write about the guy who spent decades insisting that cell phones damage your brain but left out the fact the actual process involved parasites leaping from the earpiece. I make a lot of Star Trek references compared to other pundits, but I did not think Wrath of Khan could be so relevant.

No, today I wanted to write about normalcy. But I figured I couldn’t with that elephant in the room.

I got a few paragraphs in and realized that I need to at least acknowledge the fact that it’s hard to write about normalcy when the New York Times is telling me Robert F. Kennedy Jr. battled an invertebrate homunculus. As the guy who just wanted to eat soup while watching TV without any distractions yelled while pointing at the glowing polar bear crapping iridescent green graphing calculators in the middle of his living room, “See, this is precisely the kind of thing I’m talking about.”

Similarly, I don’t want to talk about the GOP presidential frontrunner having sex with a porn actress (was she really a star?), nor do I want to hear how said actress who subsequently extorted money from her momentary paramour was ashamed of having sex with him. I don’t want any of that crap normalized. But again, what is a guy supposed to do when the normal headlines are so abnormal?

Indeed, I was going to ease into this by using a good example of the power of normal. It’s now apparent that most normal Americans see the protesting college students and their ideological handlers cheering terrorists—or even pretending to be terrorists—and say, “That’s weird. I do not like that.” That’s why, all of a sudden, a lot of promoters, apologists, and appeasers of the campus protests are suddenly chastising the media for paying so much attention to the protests.

You see, it turns out that most normal people, on the left and right, don’t like hearing young people yell, “I am Hamas!” or see cosplaying goons in masks block Jewish kids from classes or the library. And despite the desperate efforts of many in the media and on the fringe of the Democratic Party, most college students don’t want anything to do with this stuff. They don’t even care very much about the conflict in the Middle East at all. When presented with nine issues in a recent survey and asked which they considered “most important” to them, college students collectively ranked the conflict in the Middle East … ninth.

A recent Harvard poll found that 80 percent of Americans side with Israel over Hamas. I understand why Hamas supporters and apologists would consider that finding disturbing. But frankly, I think most normal people look at that 20 percent support for a group that openly calls for genocide—and proudly boasts how it will keep raping, torturing, and murdering Jews wherever they find them whenever they have a chance—and decide that is the more disturbing result.

I suspect a sizable share of that pro-terrorist 20 percent is more normal than it might seem. They may say they side with Hamas because they think Hamas is just code for “Palestinians.” Or they might have no idea what Hamas actually wants. I mean, there are some people who think Hamas is part of the struggle against transphobia and for LGBTQI rights. When students who claim to endorse the phrase “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” are informed what that actually means—and what river and what sea they’re talking about—many say, “Oh I didn’t know that. Never mind.”

But let’s broaden out. As I was saying, I like weirdness and eccentricity. But there’s a tension bordering on a contradiction in my personal preferences and my broader political ones, and I should at least acknowledge it here. I want America to be normal—admittedly by American standards. And when I say American standards, I mean bourgeois standards with American characteristics. I like the ambition of the normal American (regardless of race, creed, sexual orientation, etc.) who wants to marry a person they love, settle down, work hard, make money, succeed at their vocation, and raise as many kids as they want—who grow up to be happy, successful, normal people, with similar ambitions. Such desires aren’t for everybody—and that’s fine, too. But I think those normal desires should define normality and that normality should be defined as generally desirable and good.

What I don’t want is a country where pursuing these desires is seen as “selling out,” “acting white,” “soulless conformity,” “square,” “boring,” or some deep violation of some allegedly higher principles. I like Bohemians, the same way Ron Swanson was entertained by the hippie at the farmer’s coop. Bohemianism is entertaining precisely because it uses the broader normal society as the collective straight man for its schtick. The Romantic spirit whose rallying cry was “Shock the Bourgeoisie!” is fine and often funny in small doses. When the French poet Gérard de Nerval famously walked his pet lobster through the Tuileries gardens he explained, “It does not bark and it knows the secrets of the deep.”

That’s funny—and harmless.

The problem with the Bohemian mindset is that it is dangerous when given power. That’s because Bohemianism as a philosophy is radical, seeking to not just shock, but tear down the bourgeois order. Radicalism is the stuff of dreams, of imaginary alternatives to practical, tested, reality. And when people governed by dreams are given the power to impose their vision, they ride roughshod over reality. As Michael Oakeshott observed, “The conjunction of ruling and dreaming generates tyranny.”

That’s why I want normal politicians, not visionary ones. I want politicians who care about making sure the streets are safe while also caring that the police do not abuse their power. I want politicians who see clearing snow, collecting garbage, building roads, educating normal kids normally, and stuff like that as their primary jobs, not politicians who see such functions as a means to creating jobs for allies. I want less “vision” from the left and the right and more sound accounting principles and business practices.

The role of ideological vision in my kind of politics is to defend the vision we inherited, not to replace it or to “transform” America. There’s always room for improvement. There’s always a need for reform, somewhere. But improvements and reforms, whether of the left or the right, should be informed by a certain realism about not just what is possible, but what is good. “The man of conservative temperament,” writes Oakeshott, “believes that a known good is not lightly to be surrendered for an unknown better.”

Yeah, yeah. I’ve been doing this long enough to realize a lot of people will say that my definition of normal is both self-serving and amorphous. Guilty as charged. As Danny Ocean says when accused of having a conflict of interest when giving his ex-wife relationship advice, “Yes, but that doesn’t mean that I’m wrong.”

What constitutes normal? Reasonable people can debate this. My parameters are probably narrower than some folks, but a lot wider than others. But, heck, that’s normal. Which is to say normal countries have normal disagreements about normal things.

And I can be persuaded to adjust my parameters. The paradigmatic example of this was the argument over gay marriage. I was initially against it because it struck me as really abnormal. And, be fair: It is pretty abnormal as a historical matter. But so are equal rights for women, and I’m for those too. But the winning argument for gay marriage—at least for me and a lot of Americans—was that legalizing gay marriage was a step toward normalcy. No coincidence Andrew Sullivan—an avowed Oakeshottian—titled his book, Virtually Normal. I completely understand why some people don’t see it that way, but I’m not going to revisit that argument here, in part because it’s settled. That’s another thing I like: settled arguments.

What I mean by that is, I don’t think it’s useful or fruitful to talk about overturning our system of government. I don’t care whether such arguments come from right-wingers or left-wingers. Think of it this way: I think “real” socialism is incredibly stupid on empirical grounds. In other words, it does not work. Moreover, it really wouldn’t work here. And because those things are true, trying to impose the “dream” of real socialism would require, from the normal American’s standpoint, real tyranny.

Of course, when I say that, some people roll their eyes and say “What about Sweden or Denmark?” To which I respond, what about them? Those countries aren’t really socialist in the way the ideologues claim. Yes, they have more robust welfare states, but most of the defining characteristics of “real” socialism aren’t there. They’re mixed economies that respect private property with robust entrepreneurial sectors. Moreover, the way they pay for their welfare states is by taxing the hell out of the middle class. The American leftists who champion Nordic socialism reject the idea of paying for it with anything other than the wealth of “millionaires and billionaires” as Bernie Sanders would say. Whenever normal conservatives say that the only way to pay for our existing entitlement regime—never mind an expanded one—is by taxing the non-rich, they get outraged.

But at least there’s a long tradition of left-wingers being wrong about economics. Today, more and more people on the right have embraced Elizabeth Warren’s economics, but want them to be part of some weird “nationalist” or “post-liberal” program. Warren’s math isn’t wrong because she’s left-wing, her math is wrong because the math is wrong. Some even look to Russia as some kind of model for America, which is as stupid as looking to Castro’s Cuba as a model. I have zero problem with people who say that X country does Y better than we do. But if X doesn’t represent the relative handful of advanced industrialized democracies, they’re probably wrong or ignorant. We have nothing to learn from Russia or Venezuela or any of those countries.

If you think that Hamas has the right theory of the case, in any regard, about anything—including Israel itself—you’re weird and wrong. Normal people have good B.S. detectors. And when they hear someone defending gang rape and the slaughter of families in their beds, they’re like, “Naw, dog. That doesn’t sound right.” And when they’re told that their kid’s college graduation has been canceled because a bunch of people are defending—or celebrating—such things, and breaking the law in the process, the normal response is to recoil at the indecency of the position and to be disgusted by the cowardice and appeasement of the administrators who made it possible and subsidized it.

But I’m straying far afield. My most basic point is where I began. Our politics are so stupid right now because the elites with the loudest voices in academia, politics, and media don’t like the idea of normalcy and normal politics. Elite universities are in this mess because they got high on their own supply in the faculty lounge. Political elites—on the left and right—get high on their own supply in cable TV green rooms and on Twitter. Both parties trade power in Washington, because they win by promising to be more normal than the other party. But once in power, they don’t behave normally. So the voters throw them out and give the other party a chance at failing at normalcy.

The silent majority in America is neither a reserve army of would-be socialist or nationalist proletariats. It’s a vast sea of normal people wanting politicians to be normal, too.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.