A few of the more excitable commentators have called the attempted assassination of Donald Trump “unprecedented” in our politics, but, of course, there are many precedents—Americans are, at heart, a violent people, and the wounding of Trump isn’t even unprecedented in my lifetime.

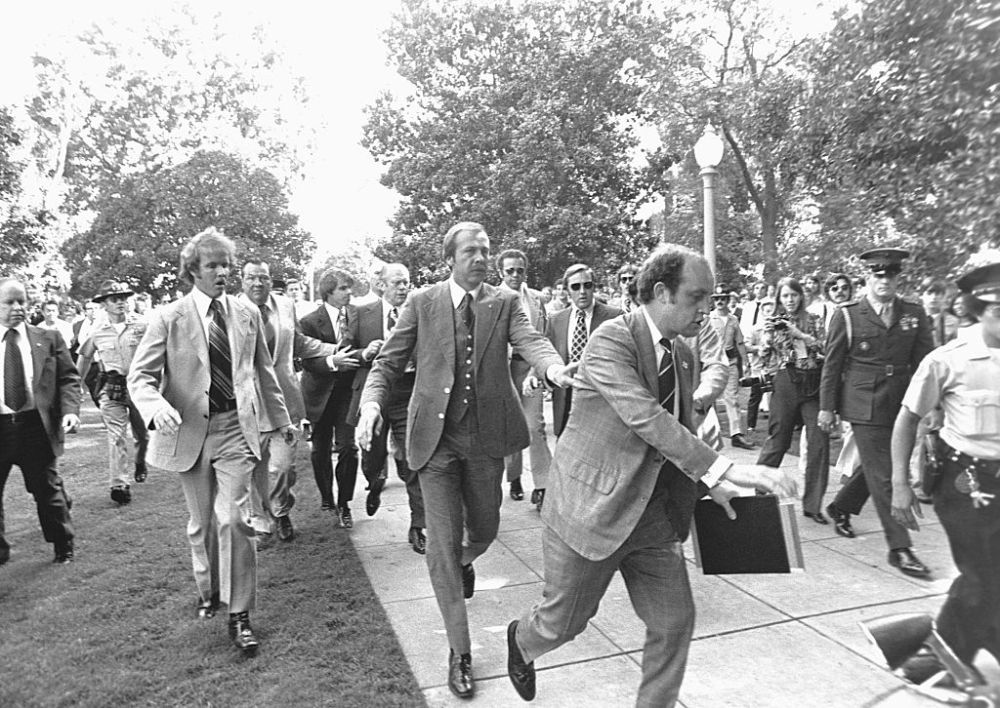

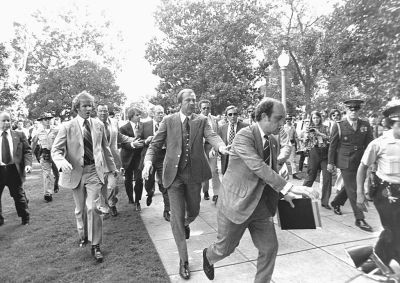

In September of 1975, there were two attempted assassinations of Gerald Ford, both of them carried out by women—radical chic meets radical chick. One of the perpetrators was a Charles Manson associate acting from environmentalist motives; the other was a more conventional left-wing radical. That kind of violent left-wing radicalism tends to draw its recruits from the children of the well-off urban and suburban professional classes in the United States, and, thankfully, neither of the women who attempted to shoot Ford knew how to handle a firearm: The first would-be assassin, Squeaky Fromme, was armed with a .45 semiautomatic with a magazine full of ammunition but no round in the chamber—she didn’t know how the gun worked. The second was armed with a more tractable .38 revolver but failed to hit Ford with any of the shots she fired.

The 1960s and 1970s were rife with that kind of thing, from the assassinations that get their own chapters in the history books—John F. Kennedy, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Bobby Kennedy, Malcolm X—to kookier episodes such as the attempted assassination of Andy Warhol by feminist radical Valerie Solanas. There is much else in our own time that is familiar from that era: a Democratic Party torn between its left wing and its more centrist faction, the radicalization of the Republican Party by an insurgent right-wing populist who spoke to racial and social grievance, concerns about crime, political riots, destructive trends in drug abuse, etc. The inflation rates we suffered through in 2021 and 2022 were almost exactly the same as in 1975, when the ladies were gunning for Ford.

Ecclesiastes tells us that there is nothing new under the sun—but what sun we have! Temperatures were above 90 when Trump took the stage in Butler, Pennsylvania, so hot that Trump had taken off his red Italo Ferretti tie and left his collar open. “A cold night is the best policeman,” a proverb has it, and higher temperatures have long been associated with violent crime in the United States. In New York state, for example, the non-NYC counties typically report more than twice as many shootings in July and August as in January and February. Political violence has a seasonal aspect, too: The Watts riots took place in August 1965; in late May and early June 2020, arson, vandalism, and looting associated with the George Floyd riots did as much as $2 billion in damage nationally, a record-breaking level of destruction.

Nothing changes—and the attempted assassination of Trump changes nothing.

If anything, the event showed Trump at his most typical, with an improvisational flair for the dramatic gesture, presenting himself simultaneously as an indomitable hero and defenseless victim. (Awfully convenient! the crackpots will say.) Joe Biden remains something very close to a disconnected nonparticipant, a mere commentator on the events of his time rather than a force to shape them. It is almost reassuring to see everybody playing his part so perfectly: The Fox News opportunists blaming Democratic campaign rhetoric for the shooting, the usual ghouls arguing in the pages of the Philadelphia Inquirer that this is really all about the need to ban semiautomatic rifles. Attempts to monetize the shooting began within minutes.

In the calendar of the French Revolution, Thermidor was the name for the hottest summer month, though “Thermidor” has come to be synonymous with the violent events of the summer of 1794, when Maximilien Robespierre was overthrown in a coup and executed, presaging the mass executions of members of the Paris Commune and massacres and repression directed at the more zealous revolutionary factions. Thermidor was taken as a turning away from revolutionary radicalism and a rejection of the Reign of Terror, but it was, of course, only a different kind of regnant bloody terror. There is left-wing terror and right-wing terror, but there is almost always terror in a revolution.

Ours is a polity founded in revolution, and, however urgently or frequently all the best people will come out this week and assure us that “there is no place for violence in American politics,” there has always been a place for violence in American politics. It is part of who we are. And this most recent episode does not turn the world upside down, as much as many partisans would like it to, thinking that to be to their advantage. Trump is still an amoral caudillo unfit for the office, a former game show host and quondam pornographer who attempted to stage a coup d’état the last time he lost an election. Joe Biden is still a dim and vicious hack who has aged out of mediocrity into impotence. Americans are still armed to the teeth and high on rage.

Nothing new under the sun, and it’s going to be 101 degrees in Washington tomorrow.

Editor’s Note: Wanderland will return to its more familiar form next week.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.