Of the hundred ways that Democrats lost the White House and Senate, one was by being pro-democracy but against republicanism.

If you were a Trump-skeptical conservative or moderate open to perhaps voting for Kamala Harris, the vice president’s support for rolling back the 60-vote threshold for most legislation in the Senate in order to codify the right to abortion access nationally after the fall of Roe v. Wade was a big warning sign. In the context of the Democrats’ post-Roe flirtation with packing the Supreme Court, the center-right received with alarm any other moves to grease the skids for majoritarian rule in the upper chamber of Congress.

After Harry Reid’s 2013 deployment of the tactical nuclear option of suspending the 60-vote threshold on most presidential appointments so Democrats could push through then-President Barack Obama’s picks for lower federal courts and administration posts, the idea that the next change to the rule—that only abortion legislation would have been exempt under Harris’ proposal—would be the last one was risible.

Even if Democrats themselves had been able to resist the temptation of expanding the power of simple majorities to other issues, Republicans surely would have cranked the ratchet when they took back control, just as they did in 2017 by adding Supreme Court nominations to Reid’s list of exemptions.

Progressives, who hate the filibuster anyway, wanted promises from Harris of bold action on abortion, arguing that since Americans were voting pro-choice in huge numbers in state referenda, allowing the minority in the Senate to blockade abortion legislation was undemocratic. Conservatives, though, say it is important to preserve the power of political minorities, and, by extension the power of the Senate to act as a stabilizing force in our politics.

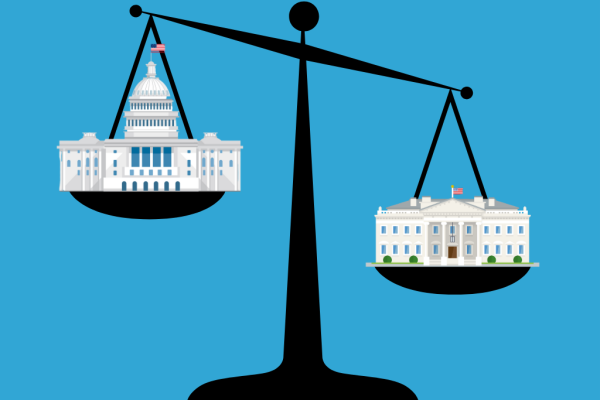

Democracy is about the will of the people, republicanism is about the liberties of persons and powers of institutions charged with protecting them, even when those things are unpopular. Our system needs both, always held in tension.

The filibuster—the privilege of individual senators to hold up the work of the entire body—evolved in the early Senate as a reflection of the Constitution’s anti-majoritarian attitude. Harris’ enthusiasm for making the Senate more representative and less cautious was therefore anathema to the small-r republicans.

In his victory speech last week after Senate Republicans won back the majority they had lost four years earlier, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell vowed “the filibuster will stand.”

“I think this shifting to a Republican Senate majority helps control the guardrails, keep people who want to change the rules in order to achieve something they think is worthwhile are not successful,” the outgoing GOP leader said in remarks no doubt aimed as much at his party as the other side.

McConnell, having lived through the push by Donald Trump in his first administration to ditch the filibuster, could reasonably expect that his successor, who will become majority leader when the new Senate convenes on January 3, would face similar pressures.

The new GOP leader will be chosen by a secret-ballot vote on Wednesday by the 49 current Republican members of the Senate, plus the three new ones elected last week (Jim Justice of West Virginia, Bernie Moreno of Ohio, and Tim Sheehy of Montana) as well as one more who probably won but is still waiting for the final ballots to be counted, David McCormick of Pennsylvania.

The contenders for the top job are Sen. John Thune of South Dakota, Sen. John Cornyn of Texas—both veterans of McConnell’s team during his 18-year tenure as party leader—and Rick Scott of Florida, a McConnell foe who failed in a long-shot bid to oust him in 2022. If none of the three candidates gets to an outright majority of 27 votes on the first ballot, the third-place finisher is eliminated and another round is held.

This initially looked like a shoo-in for either Thune or Cornyn, experienced members of leadership with prodigious fundraising records for the campaigns of their fellow Republicans. Scott got only 10 votes in his 2022 run after presiding over the party’s unhappy efforts that year as chairman of the GOP’s Senate campaign arm. And whoever won, at first it seemed the filibuster would be safe. Cornyn and Thune are both stalwart proceduralists and Scott—while unconventional on other issues—has been an outspoken supporter of the 60-vote threshold.

But then, things got weird.

Scott was always likely to be the MAGA favorite, drawing support from populist firebrands like Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin. But the outside game got cooking, with Elon Musk, Tucker Carlson, and other top advisers to the president-elect campaigning publicly for Scott. And Sens. Marco Rubio of Florida and Bill Haggerty of Tennessee, both in line for big jobs in the new Trump administration, signed on with Scott’s bid.

On Sunday came the oddest move. Trump posted on his social media platform that “Any Republican Senator seeking the coveted LEADERSHIP position in the United States Senate must agree to Recess Appointments.” Six minutes later, Scott chimed in: “100% agree. I will do whatever it takes to get your nominations through as quickly as possible.”

So what does Trump mean? In the darkest interpretation of his demand, Trump is saying that the new Senate should just go home for at least 10 days after the inauguration, which would trigger the constitutional clause allowing presidents to make recess appointments. That would give Trump the chance to pick anyone for any position without hearings or Senate approval to serve until the next Congress ends, a term of nearly two years.

Thune and Cornyn, at least publicly, interpreted it in a more benign way, with Thune saying “all options are on the table” when it comes to getting Trump’s picks confirmed, including recess appointments. Cornyn went the civics education route, explaining the constitutional authority for recess appointments. Most tellingly, both threatened to allow Trump to make these picks if Senate Democrats were to block them, which, of course, they can’t.

Thanks to Reid, it takes only 51 votes to confirm nominees. Republicans will have 52 or 53 seats. The only people who could blockade a Trump pick would be Republicans who refuse to go along.

In 2017, when Trump also had a Republican Senate, his nominees faced unusually long delays before getting a vote, mostly owing to his choice of some seriously wealthy individuals for top posts. Disclosures and ethics compliance stretched out the time to 25 days, but after that it was a snap. Trump had the final piece of his Cabinet in place by late April, one day sooner than his predecessor, Barack Obama, managed in 2009.

It seems like Trump, who hasn’t put forward anyone for a Senate-confirmed job yet who would have any trouble getting through, must have some real doozies in mind for other jobs if he is already worried about them getting rejected by his own party.

Scott’s message is clear. The Senate majority leader has broad latitude to set the chamber’s calendar, and he’s ready to use it to clear the way for Trump. Thune and Cornyn, meanwhile, seem to be saying that if they had to allow a recess appointment in order to get through a pick that was hung up for weeks, then maybe they would.

There’s no good version of the Senate in which the party in power ditches its constitutional duty to “advise and consent” on executive appointments. Not only is the duty a check on presidential power, it is, like the filibuster, a moderating force. When presidents are forced to find consensus nominees, even if that consensus is only within their own parties, it taps the brakes on ideological excesses and preserves some ethical and characterological standards for nominees.

If Republicans obliged Trump and stood back, it would set a precedent that Democrats would surely be pressured to follow when they next take control of the White House and Senate, leaving us with an even greater imbalance of power between the branches on a permanent basis.

While it seems unlikely to work, since senators, voting by secret ballot, are unlikely to reward Scott for being an enthusiastic champion of the executive branch power, it is our first big hint of what kind of relationship Trump expects to have with his fellow Republicans in the Senate. He’s not looking for a honeymoon where he and the GOP in Congress start with the stuff they all like—tax cuts, border security, etc.—before moving on to the tough stuff. The president-elect is looking for domination.

Condolences to whomever wins the vote on Wednesday, because they are either in for the fight of their lives or will get to go down in history as the man who made the Senate the vassal of the executive.

I don’t know how quickly Trump’s picks are going to get through next year, but I’ve got to give it to Republicans: To go from winning the majority to the start of a bloody internal conflict over presidential power in less than a week must be a new land speed record.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.