The time has come in this election cycle for Kamala Harris’ supporters to wet the proverbial bed.

It was always a matter of when, not if. Those on the left are (justifiably) terrified of what the other side’s victory in this race might mean for America. And if their candidate loses, liberals won’t have the fantasy of a massive vote-rigging conspiracy to console them. They’ll need to reckon with having lost to Donald Trump—again.

Even if Harris were sitting on a comfortable lead, Trump’s opponents have learned the hard way that no Democratic margin is safe when he’s on the ballot. Joe Biden led by more than 7 points in the national polling average on Election Day 2020, touching double digits in four of the last eight surveys taken. In the end, he hung on in the swing states by the skin of his teeth.

Harris doesn’t lead by 7 points. She leads by 1.8 in the RealClearPolitics national average and has fallen slightly behind in six of the seven battlegrounds. Democratic commentators have begun to fret that she’s stalled out at the very moment undecideds are making up their minds. She “made steady, incremental progress in the 10 days after the debate, but now the race has plateaued,” David Axelrod recently worried to Axios. James Carville pronounced himself “scared to death” by the state of the race.

The smell of damp sheets is also evident in the Democratic second-guessing that’s begun to, er, trickle into the media. Harris isn’t doing enough events. She needs a sharper working-class economic pitch. She should have picked the governor of Pennsylvania to be her running mate, as practically everyone urged her to do.

Ultimately, though, the case for micturition is this simple: If Americans haven’t already formed a clear preference for her over a man with more baggage than an airport conveyor belt, why would we think they’re about to do so over the next three weeks?

The situation is grim. But if keeping your bed dry is a high priority for some reason, there are certain campaign “fundamentals” you might dwell on to cheer yourself up.

In less than three months since becoming her party’s nominee, Harris has raised more than $1 billion. In tandem with left-wing outside groups, her team has built the sort of “massive door-to-door canvassing operation” that Biden’s 2020 campaign lacked due to pandemic restrictions. And voters continue to view her much more favorably now that she’s at the top of the ticket than they did when she was at the bottom.

The most reassuring argument for optimism is the fact that Trump failed to reach 47 percent of the popular vote in his first two runs for president. He stands barely above that mark in the national polling average as I write this and has spent the entire campaign since Harris’ ascension hovering around it. That’s no guarantee of defeat—he won the presidency in 2016 with a smaller share of the vote—but if he can’t do better nationally in what’s essentially a two-way race, it’s unlikely that his share in the battlegrounds will diverge so sharply as to put him over the top there.

So, Trump has a ceiling of 47 percent, and that makes him the probable loser next month. Do you buy that?

I don’t.

Raising the roof.

I guard my reputation for clownish pessimism jealously. So when I see a fellow pessimist like Jonathan Last sounding uncharacteristically optimistic, the temptation to take issue is irresistible.

Last made the case on Thursday that, for once, the polls aren’t underestimating Trump’s support. To believe that he’s going to perform 2 to 3 points better than expected this year, as he’s done in the past, you need to believe that he’s not only going to crack his 47 percent ceiling, he’s going to blast right through it.

And how plausible is that, really? “This explosion in support would follow January 6th, his felony convictions, and four years of economic expansion under a Democratic president,” Last wrote. Trump is four years older and considerably more deranged than he was on Election Day 2020; Americans aren’t just voting for “mean tweets” this time, they’re voting to absolve him of a coup plot. After all that, it cannot be that his share of the vote is going to go up meaningfully, can it?

Well, I don’t know. Can’t it?

If you had asked me during the madness following the 2020 election whether more Americans would identify as Democrats or Republicans in 2024, I would have confidently guessed the former. Democrats usually lead in surveys of party identification, after all, and that advantage would only grow from the public backlash to Trump’s authoritarian lunacy. Had I known then that he’d also end up a convicted felon facing multiple federal indictments, I’d have called the question a no-brainer. Democrats would lead on party ID in 2024, easily.

Wrong.

Gallup, NBC News, Pew Research, and the New York Times have each found Republicans ahead on that question at various points this year. Never before in Gallup’s polling since 1992 had the GOP held that advantage in the third quarter of a presidential election year, but it does now. The closest it had come previously was pulling even with Democrats in 2004—the last time a Republican won the national popular vote.

“Wow, the biggest deal in polling is when lines cross,” NBC News pollster Bill McInturff exclaimed in response to the results. In each of the last three presidential cycles, Republicans scored 43 percent in Gallup’s surveys of party ID; this year, they’re up to 48. If the GOP’s ceiling in that metric is capable of rising, why isn’t Trump’s popular vote ceiling of 47 percent?

Another illustration of the point comes from Trump’s favorability. For most of the eight years since he was elected president in 2016, his favorable rating has been remarkably consistent. With a few sporadic exceptions, he’s resided steadily in a narrow band of 42-43 percent and has typically been underwater in net favorability by 10-15 points.

Not anymore. Since early August, shortly after Harris replaced Biden as the Democratic nominee, Trump has spent nearly every day north of 44 percent and is knocking on the door of 45. His net favorability is down to -7.6 points, one of his best showings since he entered politics.

He had a ceiling in favorability, it seems—and now, suddenly, he doesn’t. If January 6 and felony convictions weren’t enough to hold down his favorable rating, why would they be enough to hold down his share of the popular vote?

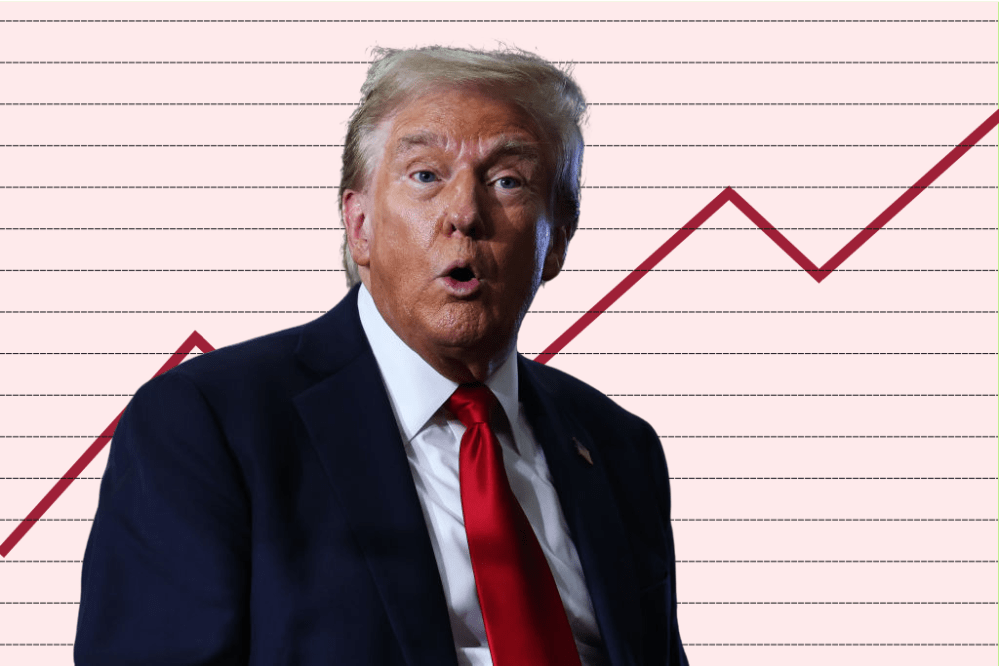

Look at this trend in Trump’s head-to-head polling over the last three cycles:

I can believe that pollsters have gotten better at measuring his true support among the electorate and that his opponents’ gaudy leads in 2016 and 2020 would have been less gaudy using the new and improved methodology. But that can’t be the sole, exclusive contributing factor for why this race is so much tighter in surveys than the previous two were, can it?

Maybe Trump’s gotten a bit more popular as well.

If polling doesn’t grab you, here’s a (very) hard number to chew on. In Pennsylvania, this cycle’s must-win state, Democrats have “their weakest voter registration advantage compared to Republicans in recent decades.” When Biden won narrowly there in 2020, his party held a registration advantage of 686,000; four years and a ton of repellent behavior by the GOP’s leader later, their margin has shrunk to less than half of that.

And if that doesn’t grab you either, consider that multiple recent focus groups of Pennsylvanians who backed Trump in 2016 before switching to Biden in 2020 have found some of those voters ditching Harris and switching back to Trump.

The truth is staring us in the face: In all likelihood, Trump’s ceiling has risen. Maybe it’s risen because Harris is a weak alternative relative to Joe Biden and Hillary Clinton. Maybe it’s risen because Trump has, unfathomably, grown stronger politically. But to count on him stalling out at 47 percent nationally next month because he stalled out there twice before smells of wishful thinking.

In fact, in this election of all elections, I wonder how much we can rely on past performance as an indicator of future results.

A moving target.

In a separate column last week, Jonathan Last himself summed up the argument for why we shouldn’t seek guidance on how Trump will do next month from how he did in the last two elections. “What if the Trump-Harris [polling] numbers are broken because the electoral coalitions have changed so much from 2020 to today?” he wondered.

Every national electorate is meaningfully different from the national electorate of four years prior. Old people die, young people turn 18, and politics evolves, remaking the parties’ coalitions at the margins. But in the Trump era, as Last rightly notes, evolution is happening at light speed. We’re living through a full-bore realignment as a pro-business, pro-life, interventionist GOP transforms itself under a leader who’s protectionist, isolationist, and agnostic about state abortion bans.

As the party shifts, voters are shifting with it. One analysis of recent voting patterns in Pennsylvania found Democrats’ advantage has shrunk more in Philadelphia than in any other county, particularly among “working-class communities where ‘education levels were lowest and poverty rates were highest.’” The Harris campaign is so worried about black men in particular peeling off toward the GOP that Barack Obama has been enlisted to chide them en masse to stop being so sexist toward Harris.

Trump had a ceiling of 47 percent when Democrats and Republicans were still relying on their traditional coalitions, more or less. What ceiling does he have now that the puzzle pieces of national elections have been tossed into the air, leaving Liz Cheney supporting Democrats and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. supporting Republicans, with no one sure where any of them will land until the votes are in next month? I can’t think of a good reason to assume that it’s still 47 percent.

But you don’t need realignment to formulate a theory for why this election might be different from 2016 and, especially, 2020.

If you’re cynical about American voters, you might wonder whether being black, a woman, and relatively unknown has created a special burden for Harris. Trump’s ceiling might be 47 percent when he’s facing a white opponent with whom voters have gotten comfortable over decades, like Biden and Clinton. When he’s facing a nonwhite cipher like the current vice president, maybe it’s 48 percent. Or 49.

Trump has also never run before against a de facto incumbent. Clinton was incumbent-ish in 2016 insofar as she had served in Obama’s Cabinet, but she was a figure of sufficient public stature in her own right that most of the baggage she carried was her own, not her former boss’. Harris lacks that stature: Try as she might to distance herself from Biden’s record—and she’s not trying nearly hard enough—she’s suffering for his sins. In the latest Wall Street Journal battleground poll, Trump leads her by 10 points on the economy, by 11 on inflation, and by 16 on immigration.

Because he’s a former president running for his old job, he can also fill an unusual niche that he couldn’t fill in his first two campaigns. In 2016, Trump was the “change candidate” but untested; in 2020, he was the incumbent, making Biden the candidate of “change.” This year he can posture as both the experienced leader on the ballot and as the “change candidate,” having already passed his job interview for president once before—God have mercy on us all—while Harris flails in interviews to try to pass her own. That also might be worth an additional point or two in the popular vote.

And how much is it worth to him, do you suppose, that Americans have gradually grown desensitized to his insanity after years of exposure to it?

One of the grimmest polls I’ve seen this year is the result of California’s student mock election. With more than 71,000 ballots cast across 235 middle and high schools, the state’s students prefer Kamala Harris to Donald Trump as president—but only by a margin of 49-35, not even a majority. In 2016, the same mock election found Clinton winning 59-20. In 2020, Biden romped 68-18. It seems elementary to me that the more Trump is “normalized” over time, especially by young voters with no memory of pre-Trump politics, the fewer votes he’ll lose due to misgivings over “norms.” And the higher his ceiling will rise.

Finally, we come to the X factor: How many more “low-engagement” voters might turn out this year for Trump than turned out for his first two runs for president?

In polling across seven swing states, Dave Wasserman of the Cook Political Report found that mid- and low-engagement voters were more likely than high-engagement ones to be female, young, and nonwhite, all of which should make them better disposed on average toward Harris. But right now, they’re leaning Trump: He leads by 7 points among that cohort, almost entirely offsetting the Democrat’s 4-point-lead among high-engagement voters.

Disengaged voters have been Trump’s secret sauce all year, even when Biden was still in the race, and I’m sure he knows it. From his extreme-even-by-his-standards demagoguery to his ludicrous panders on economic policy to his cameos in “bro” media, Trump’s using every gimmick he can think of to grab the attention of Americans who don’t normally pay much attention to politics.

If he turns them out in unexpectedly large numbers, he’ll expand the electorate. And in an electorate that includes lots of new and “irregular” voters, there isn’t much insight to be gleaned from Trump’s previous popular vote share about how high his ceiling might rise.

So why do many of us, including me, cling to the hope that the 47-percent ceiling will hold?

Hope and denial.

Isn’t it obvious? The truth is painful, and none of us want to face it until we have to.

That bitter truth is that Trump is stronger politically now than he was before January 6, before his coup attempt, and before his criminal indictments. No one with a civic conscience wants to believe that such a thing could be possible in America. It’s always been embarrassing that he’s competitive in national elections, and it’s always been egregious that he once actually won. But in 2016 and 2020, one could at least retreat into the delusion that voters would punish him if he ever did something really bad.

Well, he did something really bad. And now there’s reason to think he’ll win a larger share of American votes after doing that really bad thing than he did in his previous two campaigns, even if he ends up losing. A man whose own handpicked Joint Chiefs chairman describes him as “fascist to the core” has paid, and apparently will pay, no discernible electoral price for it.

We all care deeply about the outcome of the election. A lot more than just policy rides on it, of course. But if you’re treating it as a temperature check on the public’s basic decency, you don’t need to wait until November to get a reading. Nate Silver recently compared the probability of a Trump victory to the probability of a direct hit from a hurricane: Whether it’s 40 percent or 52 percent, you’re in the “Cone of Uncertainty.” The odds of a catastrophe are frighteningly high.

The same goes for Trump’s popular vote ceiling. Whether it’s 47 percent or 48 or 49, a coalition of people big enough to win a presidential election prefers to be governed by this man again, despite everything they’ve seen from him since Election Day 2020. And, win or lose, those of us who don’t prefer it will have to coexist with them somehow and pretend that that’s more or less fine.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.