Dear Capitolisters,

One of the more common criticisms of the global trading system—by which I mean the World Trade Organization, regional trade agreements like NAFTA, and the various national governments and private parties acting within this general framework—is that it’s simply incapable of handling China’s “state capitalism” economic model and authoritarian regimes’ potential “weaponization” of trade to achieve their economic and geopolitical objectives. As I and others have written, both academic research and recent experience (see, e.g., Russia and natural gas) poke holes in this thesis, but recent events compel me to revisit it once again. In particular, we’ve seen in the last few weeks both the system working just as intended and the embarrassing failure of its supposed alternative—one (unfortunately) led by the United States.

The Australia-China Example

First comes a widely publicized dustup between China and Australia, which arose in 2020 when then-Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison called for an international investigation into the origins of COVID-19. In typical “Wolf Warrior” fashion, Beijing responded quickly by not only complaining about all the ways Canberra had offended China, but also not-so-quietly targeting certain high-value (and politically sensitive) Australian imports. This included certain raw materials (coal, iron ore, etc.), as well as barley and wine, which were each subject to new “anti-dumping” investigations—eventually leading to tariffs—launched by China’s Ministry of Commerce. (Hey, remember how I said U.S. dumping cases were routinely abused? Yeah, China does it, too.) One Chinese official even went so far as to paraphrase Bruce Banner: “China is angry. If you make China the enemy, China will be the enemy.”

Xi Smash, etc.

Shortly after the bilateral conflict began, we were treated to numerous warnings that it was a perfect example of how China could “weaponize globalization” by targeting key imports and exports—and how the entire global trading system is simply unprepared for such vulnerabilities. Authoritarians, so the theory went, can use state enterprises and economic coercion to attack pain points in global supply chains, eventually bringing smaller countries to heel. Australia was learning this lesson the hard way. It was all very sad and scary, and it justified a fundamental rethink of the global trading system and the WTO.

Then, a funny thing happened: nothing.

Well, not nothing, but certainly no catastrophe and, in fact, much the opposite. Today it’s Beijing, not Canberra, that’s mostly retreated. Here’s how it all went down.

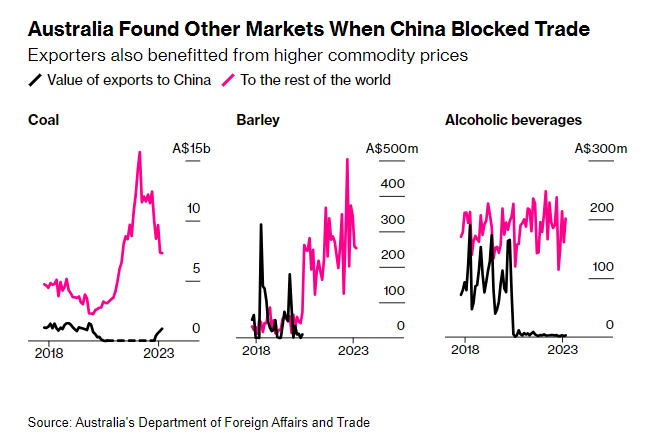

First, the Australian government challenged the Chinese barley and wine actions at the World Trade Organization, alleging that the investigations violated various WTO disciplines on member countries’ anti-dumping measures. At the same time, private actors also got to work. Australian exporters looked to other markets—coal to India, barley to Mexico, etc.—and in most cases importers and consumers (including your shiraz-enjoying correspondent) were eager to oblige:

Canberra also tried to help its exporters diversify by accelerating negotiations on free-trade agreements with the United Kingdom (since completed), the European Union (stalled), and India (completed). The result was more trade diversion than destruction:

China’s trade sanctions against Australia began around May 2020 and ramped up in the subsequent months. By early 2021 however it was already obvious in the trade data that the economic impact would ultimately prove relatively minor. Australian exports to China in affected sectors dropped sharply but this was largely offset as Australian exporters for the most part successfully diverted their goods to other markets.

China also found itself unable to find alternative suppliers for certain products that its consumers and economy needed. In 2021, for example, the Chinese government quietly unbanned imports of Australian cotton and copper that its companies couldn’t source elsewhere:

Not only does this show China’s pragmatism towards trade, but that countries which have weaponized trade cannot always “win,” said Tianlei Huang, research fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

“China, like the U.S., often weaponizes trade in order to achieve political objectives. Sometimes it works, but sometimes it does not. In the Australia case, it seems China’s sanctions have yet to yield any real satisfactory results,” he said.

Although some domestic producers and exporters felt some pain from lost sales, new government data show that, because of this trade diversion—and the fact that the targeted exports were a relatively small part of Australia’s economy—the nation suffered a miniscule amount of economic damage overall:

The impact of China’s coercive trade sanctions was to reduce the total value of Australian exports to the world by just 0.2%. Incorporating other impacts (e.g. on prices, the exchange rate, foreign investment), the Productivity Commission estimates a reduction in Australia’s GDP of less than one-hundredth of a percentage point. Adding in a slight worsening in Australia’s terms of trade (prices for Australia’s exports versus imports) and the Productivity Commission estimates a reduction in the purchasing power of Australia’s real national income was a bit larger—but still tiny, at less than one tenth of a percentage point.

Fast forward a few more months, and Beijing appears to have realized this futility, too. In August, China announced it would remove tariffs on Australian barley imports—the result of Beijing agreeing in April to review the anti-dumping measures in exchange for Australia pausing its WTO dispute. Just last week, the two governments made a similar agreement on wine, and China has started importing Australian coal again, too.

Yet, even after the reversals, China may end up worse off because the government’s antics:

Even with the tariffs lifting, Australian barley exporters will remain cautious of rushing back to China. Many have found new markets, boosting shipments to Saudi Arabia, Japan, Vietnam, Kuwait and Mexico. “It’s important to note that Australia found alternative buyers of barley while the Chinese anti-dumping tariffs were in place,” Rabobank agricultural analyst Dennis Voznesenski said. “A risk premium will likely be required, at least initially, for exporters to redirect trade flows into China.”

Well, would you look at that.

Par for the Systemic Course

While things don’t always work out so well, history shows that these results are far more the rule than the exception when it comes to state capitalism, “weaponized” trade, and the global trading system. As I wrote a few years ago, for example, Chinese government efforts to restrict “rare earth” minerals failed a decade ago for reasons very similar to the ones that boosted Australia: After global rare earths prices initially spiked, governments and private companies quickly moved to diversify supplies, and several governments (including the United States) filed WTO disputes that China would eventually lose. After a year or so, the global market settled, prices dropped, and Beijing backed down thereafter (conveniently blaming the WTO loss for what the market had already adjudicated). More recent scares regarding lithium and cobalt have also proven empty (so far). And just this week, markets reacted calmly and predictably—with relief, even!—to new Chinese government threats to restrict graphite exports:

The story is similarly uplifting at the WTO, where—contra the conventional wisdom—most of China’s bad economic behavior (e.g., on anti-dumping abuse, industrial subsidies, or intellectual property) is covered by existing WTO rules and can be litigated through dispute settlement. (Reminder: I used to do this kind of trade-lawyering as a job and analyzed these kinds of hypotheticals many, many times over those two decades.)

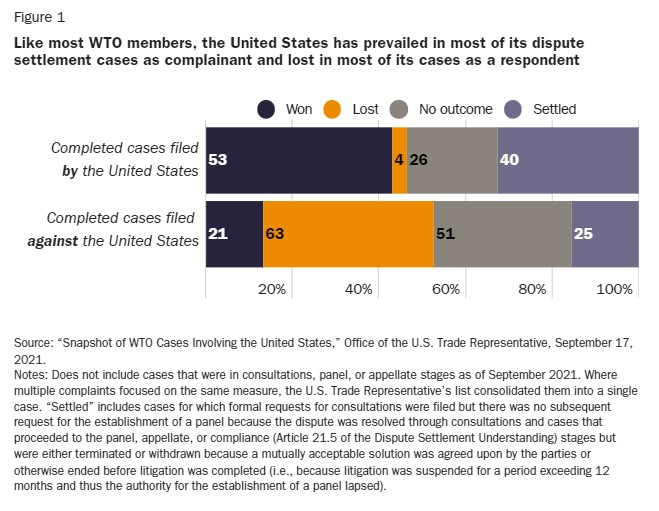

When governments have challenged China, moreover, the process has proven pretty effective: The United States itself has a sterling record, and, as my Cato colleagues wrote a few years ago, China tends to comply (removing the offending measure or otherwise improving access to its market) when it loses a WTO case. As the Australian barley and wine cases show, China often retreats (via settlement) before a case is decided, too. Chinese compliance isn’t perfect (nor is any other WTO member’s), but it’s decent overall. Indeed, it’s arguably better these days than that of the United States, which has famously shirked WTO rulings on subsidies, anti-dumping rules, internet gambling, and—as we’ve recently discussed—tariffs on metals and Chinese imports.

But this success isn’t just (or even primarily) about China. As James Bacchus—my current Cato colleague and the former chair of the WTO’s Appellate Body—just wrote in a great new explainer essay on all things WTO, the United States generally wins any challenges it brings, and all members tend to comply when they lose because they so value the system that such (voluntary) compliance supports:

WTO members—for whatever reason they choose—remain free to ignore WTO rules and rulings, as long as they are willing to accept the loss of previously granted trade concessions as the agreed price for making that choice. This price can sometimes total billions of dollars of lost trade benefits annually, which—along with a desire to maintain the multilateral system and their government’s status therein—has usually proven a strong incentive for WTO members to comply with the rules and the rulings. Noncompliance has thus, until the recent recalcitrance by first the Trump administration and now the Biden administration of the United States, been rare.

Today, of course, that value has been diminished—in large part because of the myth that the WTO has fueled China’s rise and failed to discipline its abuses. But as Bacchus explains, that latter failure isn’t really the fault of the institution or rules themselves; the blame lies primarily with WTO members, who have simply refused to bring more disputes:

China’s economic rise poses a unique challenge to the world trading system, but WTO dispute settlement has more potential to address China’s practices than most U.S. politicians and pundits understand. Indeed, the United States could today file a lengthy list of legal challenges to an array of Chinese trade practices under existing WTO rules, including on intellectual property protection and enforcement; trade secrets protection; forced technology transfer; and subsidies. The unfortunate reality is that, for the most part, the United States and like‐minded members have not filed these challenges. Furthermore, the WTO—as a member‐driven organization—cannot unilaterally initiate or adjudicate them. The failure to bring these potential legal claims against China is particularly disappointing, given that China does not—also contrary to myth—routinely ignore adverse WTO rulings.

As I’ve noted here before—and as Bacchus makes clear in his essay—the WTO certainly isn’t perfect. Most importantly, disputes are slow and hyper-technical, and achieving consensus in negotiations among 164 nations is beyond difficult. But as Bacchus notes in this essay and a separate paper, there are relatively easy procedural changes that can fix most of these shortcomings, while maintaining a system that has worked pretty darn well. New substantive rules to address specific concerns about “state capitalism” or 21st-century issues like digital trade could also be useful. But none of this justifies abandoning the WTO and the rest of the global trading system as the United States has done in recent years—especially given the alternatives.

The Alternative Isn’t So Hot

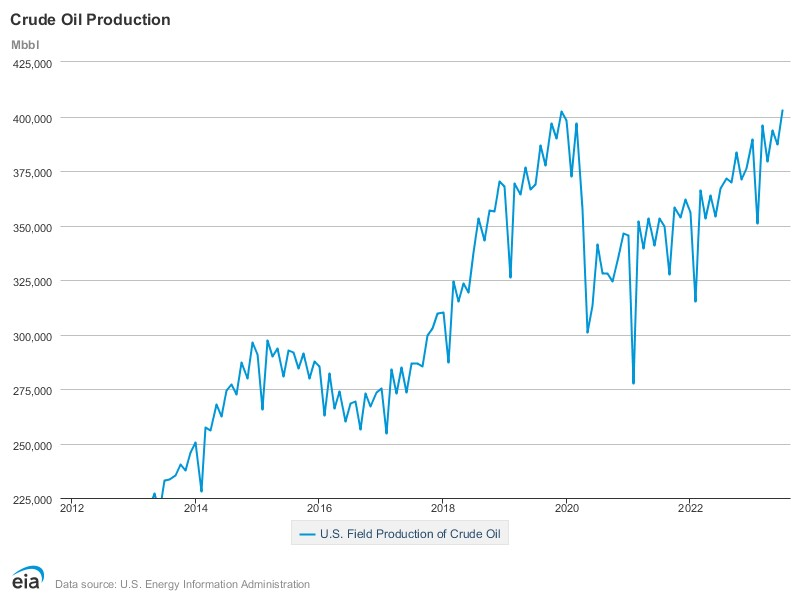

And that brings me to the other big trade news of the last week: After more than two years of trying, the United States and the European Union (EU) announced Friday that they’d failed to resolve their disagreements over Trump-era “national security” tariffs on steel and aluminum and create a new agreement on trade in climate-friendly metals. As I detailed last December, President Trump imposed those tariffs on a global basis back in 2018, and—to the surprise of no one—they’ve since been ruled WTO-inconsistent after several countries challenged them in dispute settlements. The Biden administration—which has maintained most of the tariffs and has converted the rest (including for Europe) into quotas—flatly rejected those WTO rulings (imperiling the entire system in the process), saying the WTO can’t judge America’s “national security” invocations, no matter how bogus.

At the same time, the administration has tried to convince the Europeans to ignore all that and turn the “national security” tariffs into a narrow agreement on “environmental” tariffs that they’d both employ to (supposedly) target dirty steel from China. (Note: If you’re confused as to how the United States can, on the one hand, tell the WTO that it can’t question its “national security” tariffs but, on the other hand, work to change those same tariffs’ justification to climate change, you’re not alone. It’s one of those things that only makes sense in the minds of law professors, politicians, and journalists with short attention spans.)

As the Financial Times’ Alan Beattie summarized on Monday, the EU was having no part of this plan. So, the U.S. tariffs on European steel and aluminum remain “suspended” (but not really, because they’re still subject to a quota arrangement), and “the two sides didn’t even get the critical minerals deal which was supposed to be the meeting’s deliverable.”

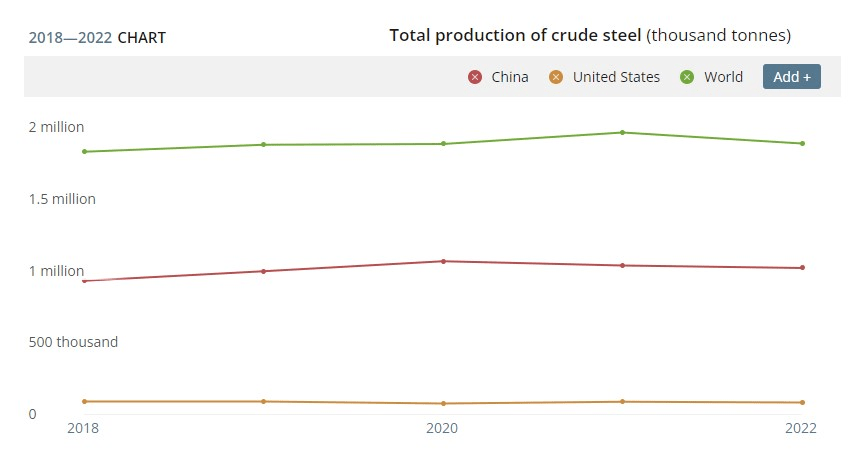

As Beattie goes on to explain, the talks’ failure was “predictable” for several reasons. Most notably, the U.S. proposal would likely undo the EU’s efforts to make its climate change regime—a combination of a domestic carbon pricing mechanism and a substantially equivalent “border measure” (or “CBAM”) applied to all imports, regardless of source—consistent with WTO rules, which arguably allow for non-discriminatory border measures that mirror domestic taxes. One can reasonably question whether the EU system is actually WTO-compliant, but the U.S. approach is almost certainly not (beyond the whole “national security” ruse): The U.S. has no carbon tax or pricing system to which a border measure would be matched (so, it’s just a protectionist tariff); the proposal would also punish subsidies, which are disciplined by WTO rules and other national laws subject thereto; and the proposed methodology for calculating national carbon intensity “essentially uses a green smokescreen to protect America’s relatively inefficient and carbon-heavy blast furnaces from further decarbonisation and international competition.” Thus, EU officials have long said they won’t sign on to “agreements which manifestly violate World Trade Organization rules”—like this one!—while defenders of the U.S. approach have openly said that pesky WTO concerns shouldn’t dictate any deal.

Combine this problem with the fact that, as Bloomberg notes, the Biden administration even refused to fully terminate the WTO-inconsistent Trump-era tariffs, and you get from all this WTO-circumvention, well, nothing—even as the evidence of the tariffs’ costs and inefficacy (including by affecting overall Chinese trade or disciplining global steel overcapacity) piles up.

The alternative to the much-derided global trading system, it turns out, is even worse—something the EU, Australia, and other WTO members still appear to understand.

So why, then, does the United States seem so insistent on said alternative, while leaning heavily into tariffs, subsidies, local content mandates, narrow trade agreements, and other WTO-inconsistent measures that—up until very recently—it vocally opposed?

As Beattie explains, it’s just the same old protectionist politics and one industry in particular—steel—that’s inexplicably captured U.S. trade policy to the detriment of almost everyone else:

An increasingly capital-intensive industry, it doesn’t create many jobs these days. Costlier steel means higher input costs for the rest of manufacturing and construction: there are 80 jobs in downstream steel-using industries for everyone in steelmaking.

And so here we are. Ridiculously, steel played a massively disproportionate role in creating US disillusionment with the WTO thanks to an interminable dispute over “zeroing”, a particular methodology for constructing antidumping margins much used by the industry. It’s definitely a lucrative job-creation scheme for trade lawyers. Trump’s WTO-hostile USTR, Robert Lighthizer, was a former steel industry attorney who drove a Porsche. (Thinking about it, buying an imported car is grimly appropriate given the role of tariff-inflated steel prices in making US auto production uncompetitive.)

In fact, Washington’s proposal to gang up on China is particularly pointless given existing US and EU antidumping and antisubsidy duties on Chinese steel. … Simon Evenett and Fernando Martín of the Global Trade Alert project, reliably on hand to deflate policymakers’ windy rhetoric with inconvenient facts, note that China sells less than 7 per cent of its total steel exports (and less than 24 per cent of its aluminium exports) to the EU and US combined. This isn’t enough of a stick to get China to change its emissions intensity.

In short, the big “green steel deal” with the EU isn’t really about “green steel,” or even China at all: It’s about maintaining Trump-era tariffs and keeping the WTO sidelined so it won’t further tarnish the U.S. trade remedies system and other political sacred cows (like farm subsidies)—at least until 2025. Indeed, in the run-up to last week’s U.S.-EU summit, European officials openly admitted to the Financial Times that the agreement was motivated by “the need for president Joe Biden to protect steelworker jobs in swing states such as Pennsylvania and Ohio to prevent Trump winning an election rematch next year.” And if delivering those rents means dubiously using a “national security” law to enter into an environmental side deal that lets you maintain costly, WTO-inconsistent tariffs, then so be it.

But spare me the “system is broken stuff,” okay?

Summing It All Up

Last week’s non-event certainly isn’t the only example of continued U.S. struggles to create an alternative to the global trading system it’s essentially abandoned—see, for example, here, here, and here—but it’s still noteworthy for both its brazenness and timing, coinciding so well with Australia’s near-total victory in its yearslong trade disputes with China. “Weaponizing globalization,” it turns out, is a lot harder than it sounds, thanks to both dynamic, open markets and a global trading system some (ahem) have left for dead.

None of this means, of course, that the United States and other governments should simply do nothing in regards to China or the WTO, or that—as Kevin noted in his (great) newsletter this week—there aren’t legitimate exceptions to general free trade rules and principles. (Indeed, the WTO agreements expressly include many of these exceptions, including for national security—but, unlike the U.S., you have to actually follow their terms.) Yet, as the last week shows, the vast majority of U.S. resistance to the multilateral trading system has nothing to do with actual efficacy of the system itself, which, even after being hobbled (by the United States), can still get governments to change course or, as with China and rare earths, give them a face-saving excuse to do so.

Instead, U.S. opposition to this system has been and will remain primarily about politics: An increasing number of Republicans and Democrats really like how national trade and subsidy laws deliver rents to the steel industry, labor unions, and other small but influential interest groups; they see political value (and/or necessity) in maintaining or expanding those laws to win elections; and they see the WTO as a pesky impediment to achieving these political goals. So, we’re treated to grand speeches from U.S. trade representatives in multiple administrations about how “the system” can’t handle China (after barely even trying to use it) and how free-trade agreements are dead, even as other countries still use the system successfully and are busy signing new trade deals—including to counterbalance China.

Meanwhile, as this past weekend’s EU deal debacle shows, the alternative to the slow, messy WTO isn’t some world in which China backs down and the USA emerges victorious. It’s actually messier, more opaque, and overall worse—for us and the world.

But, hey, maybe the political calculation is correct and the Biden administration’s positions on trade, tariffs, and the WTO really are necessary to win in the midwest and other important areas (I remain skeptical). They should just admit as much instead of pretending the system was broken before they started breaking it.

(Oh, and go Rangers!)

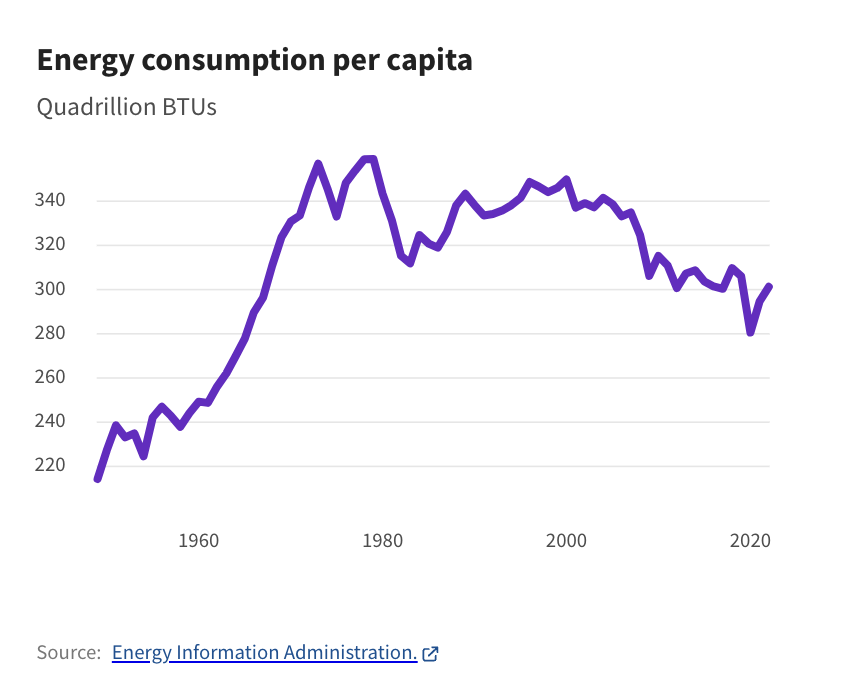

Chart of the Week

The Links

New Defending Globalization essays:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.