Dear Capitolisters,

A little more than two years ago, a lot of U.S. politicians and wonks were worried about cobalt, a mineral central to the production of the lithium-ion batteries that power everything from smartphones to electric vehicles. Politico reported in December 2020, for example, that “China’s state-directed industrial policy has outmaneuvered America’s laissez-faire approach to securing access around the world to a metal that’s taking on growing economic and strategic importance.”

The story went on to explain that two decades of Chinese government “strategic thinking” on cobalt (and other key minerals) put China at the center of the cobalt supply chain, making it “one of the materials at highest risk of supply disruptions.” This risk, we were told, had serious economic and security implications that had Washington rethinking its hands-off approach to “critical minerals”—instead contemplating subsidies, tariffs, and other industrial policies to secure future access to these scarce, vital resources.

Back then, I took to Cato’s blog to caution—as I’m known to do—that hysteria about widespread China-related shortages of cobalt was very likely misguided. My warnings, as they’ve sadly been in recent years, were ignored: Since 2020 the federal government has implemented an array of industrial policies to ensure U.S. access to cobalt, including substantial new subsidies for cobalt production in the 2022 IRA (aka The Bill that I Shall Not Name).

Fast forward two years, and I’m greeted by this delightful headline in The Economist:

The writer explains how several market factors—not major government interventions—turned what appeared to be a huge supply chain crisis into a veritable nothingburger. First, overall demand for batteries waned a bit as pandemic-fueled consumption of laptops, smartphones, and other electronics declined, and as higher interest rates more generally cooled aggregate demand around the world. Second, demand for cobalt specifically declined because EV manufacturers “have done their best to reduce use of the formerly super-expensive metal.” The Financial Times elaborates that this diversification is owed to a major “shift in the Chinese electric vehicle market towards lower-range batteries that do not use cobalt” and because these and other automakers “have been pushing to develop battery chemistries that use less cobalt,” thanks to high prices and concerns over child labor in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which produces a lot of global cobalt supply.

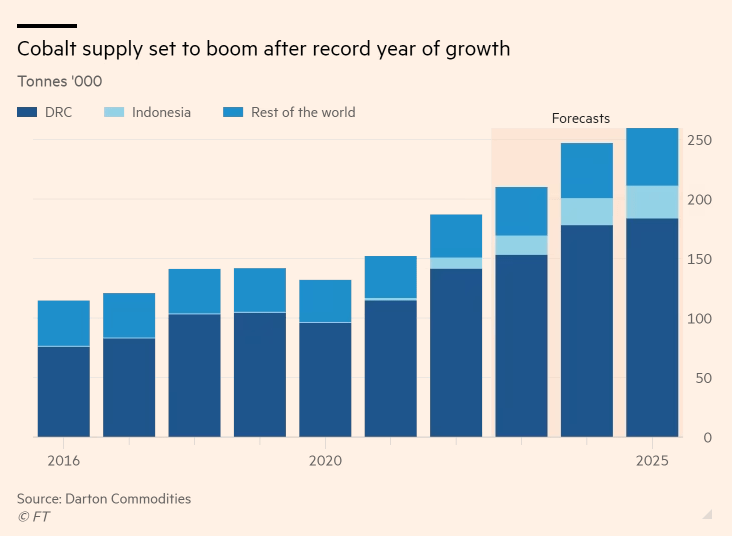

Third, the global production of cobalt has increased—not only in the DRC, but also in Indonesia, which saw exponential output growth over the last few years. Other (smaller) supply has also come online, and DRC production might grow even more, if the DRC government lifts export restrictions on a major mining company caught up in a tax dispute there.

Finally, The Economist notes that investors, including Chinese companies and Swiss multinational giant Glencore (which has investments in both the DRC and Indonesia), are—even amid the current supply-demand situation—doubling down on investment in future cobalt production. The following chart from the FT shows that 2025 supply is forecast to be more than 25 percent higher than it was last year:

Reduced demand, increased supply, and more investment (and future output)—driven mainly by high prices and future bets on the market for battery materials—have predictably caused cobalt prices to collapse. That’s a far cry from the shortages that many predicted a little more than a year ago.

And, it should be noted, this all happened before any major U.S. industrial policies have had time to do their thing: “In the US, Washington’s concerns over China’s dominance of the cobalt supply chain have led to substantial incentives for cobalt production domestically or in countries deemed friendly to America. However, those incentives, codified in the Inflation Reduction Act, will take years to yield any results.”

The only operational U.S. cobalt mine—we stopped cobalt mining in the 1980s due to environmental concerns (rightly or wrongly)—came online in late 2022 after a $100 million investment (from an Australian company) that was initiated in 2019.

The Economist then concludes with even more cobalt optimism for the future:

Prices may still rise a bit this year, as speculators seek to snap up bargains. Beyond 2025, however, another dampener looms. By this time, the first wave of electric-vehicle batteries, which typically last up to eight years, will begin to be recycled, reducing the need for new supply. No matter how fast the energy transition speeds up, the blue gold is unlikely to act as a brake.

(Admittedly, by that time some of the U.S. subsidies—e.g., for battery recycling—could be at play here.)

How did I know that this would all happen? Well, I didn’t—at least, not exactly. Instead, this “superabundance” is what usually happens when markets are allowed to adjust and humans—motivated by prices, profits, and other things—are relatively free to innovate and trade. Indeed, as you’ll recall from a previous Capitolism newsletter, my Cato colleagues Marian Tupy and Gale Pooley just wrote a whole book about it, which economist George Gilder summarized as follows:

Going back to 1850, the data collected by [authors] Tupy and Pooley show that for more than a century and a half, measured by time prices, resource abundance has been rising at a rate of 4 percent a year. That means that every 50 years, the real-world economy has grown some sevenfold. Between 1980 and 2020, while population grew 75 percent, time prices of the 50 key commodities that sustain life dropped 75 percent. That means that for every increment of population growth, global resources have grown by a factor of 8.

As I noted back in 2020 when writing about the cobalt hysteria, in fact, similar market adjustments had previously occurred for other “rare earth minerals” on which China was supposed to have a stranglehold: When the Chinese instituted an export tax to lower domestic prices and boost its mineral-consuming industries, prices outside China spiked and everyone went scrambling for supply alternatives. About a year later, prices had collapsed, and the Chinese government backed down.

Indeed, as I noted, there were already signs in 2020 that markets would also (eventually) alleviate any future cobalt crisis in a similar way:

At this stage, global cobalt demand is not projected to outstrip supply until 2023, and prices today show little concern over a future supply disruption. Nevertheless, the risk alone — due to U.S.-China tensions, continued problems in the DRC, or other factors — is already leading to predictable market responses. In particular, private investors are pursuing non‐Chinese cobalt projects (the aforementioned Jervois outfit just raised A$45 million, for example), and manufacturers like Tesla and IBM — as well as academic researchers — are already starting to develop alternatives cobalt‐based lithium‐ion batteries for electric vehicles and other uses. The USGS also notes that the U.S. government has already stockpiled several hundred metric tons of cobalt in case of military emergency, and that private companies have their own substantial inventories.

Today’s “cobalt superabundance” (and, apparently, tomorrow’s) could very well mean that those government stockpiles are never needed. Huzzah.

Why did nobody listen to us market optimists back in 2020—especially when there are books-worth of evidence arguing against resource-related hysteria and for (cautious) optimism about human ingenuity and future abundance. Why did everyone freak out (again)?

Well, beyond the simple fact that, as Superabundance details, humans are hardwired to adopt a zero-sum, scarcity mindset, we optimists on Team Superabundance usually can’t point to a specific “thing” or set of things—specific transactions, policies, whatever—that will definitely, positively resolve a market situation that currently looks rough and thus has people worried about future supply. Markets are unimaginably complex—consisting of millions upon millions of actors responding in real time to millions upon millions of different signals in ways that no single person (or group of people) can predict—so who am I to boldly dictate a specific plan or solution? So, while we can and should be relatively confident that things will eventually work themselves out, humility demands we avoid confident recommendations that specific microeconomic levers be pulled.

Team Scarcity, by contrast, can both point to both a specific, scary here and now (demand outstrips supply, prices are high, and bad guys control production!) and then boldly identify a scientific-sounding “solution” (Subsidize our supply! Block their imports! Maybe tax—or maybe subsidize—demand too! Whatever!) that various static, backward-looking models show will quickly fix the problem in a very simple and linear sort of way.

And in Washington and other capitals around the world, Duke’s Mike Munger explained recently, this “plan” beats our “no plan” almost every single time:

[A] recommendation to do something, and the claim that “we have a plan,” is always going to be a competitive advantage in politics and elections; the claim that we don’t know anything, and state intervention is likely to do more harm than good, is simply untenable as a policy recommendation. …

Most economists, if you have a sober conversation with them in private, readily admit that models are at best temporary approximations, and can be misleading. But anyone who wants to work for the government, or to be listened to by important officials for advice, must pretend to believe that models are specifically informative, and in particular, that their personal pet models are the best. In short, the problem is not so much our reliance on economics as our reliance on politics. Politics insists that we must pretend to believe in the fiction of central direction of markets as effective policy.

Never mind, he adds, that all this “doing something”—based on “bad models, advanced with smooth confidence and the authority of rafts of dogmatic-but-refereed journal articles”—might actually make things worse than doing nothing at all. Inside the Beltway, when a momentary problem has been identified and immediate solutions are demanded, Nobel laureate F.A. Hayek’s “pretense of knowledge” will almost inevitably win the day.

What’s a market optimist supposed to do when “yes, do nothing” is an inadequate response to a Senate staffer (or almost anyone else) worried about cobalt, or rare earths, or European natural gas consumption, or anything else? Here, again, Hayek’s famous speech is instructive:

If man is not to do more harm than good in his efforts to improve the social order, he will have to learn that in this, as in all other fields where essential complexity of an organized kind prevails, he cannot acquire the full knowledge which would make mastery of the events possible. He will therefore have to use what knowledge he can achieve, not to shape the results as the craftsman shapes his handiwork, but rather to cultivate a growth by providing the appropriate environment, in the manner in which the gardener does this for his plants.

In practice, this means we can point to the modern world’s long history of adjustment and eventual resource superabundance and can advocate policies that let markets do their thing—price signaling, production and consumption adjusting, individuals innovating and trading—with limited state (and regulatory) intervention, all while remaining humble about how the specific plants in our now-weeded and fertilized “garden” will bloom. And, to the extent the government’s “do something” itch still needs to be scratched, relatively unintrusive policies, such as government stockpiles or “strategic” reserves, could then be proposed (though these also can raise risks). I don’t for a second think that this approach will always win the day—*he says as he gestures around wildly*—but it’s still worth a try, especially given the bad alternatives and repeated “crises” that, as with cobalt, never materialized.

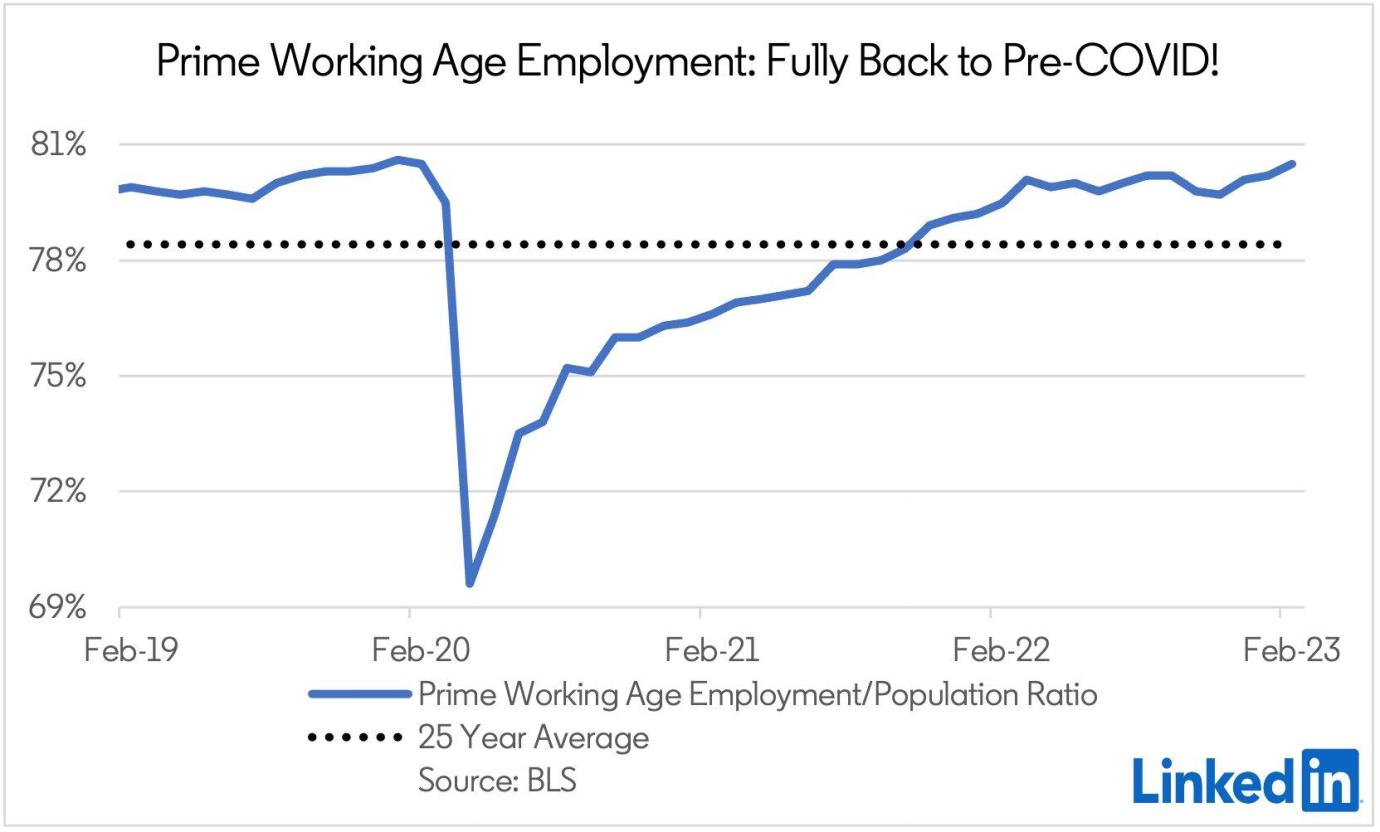

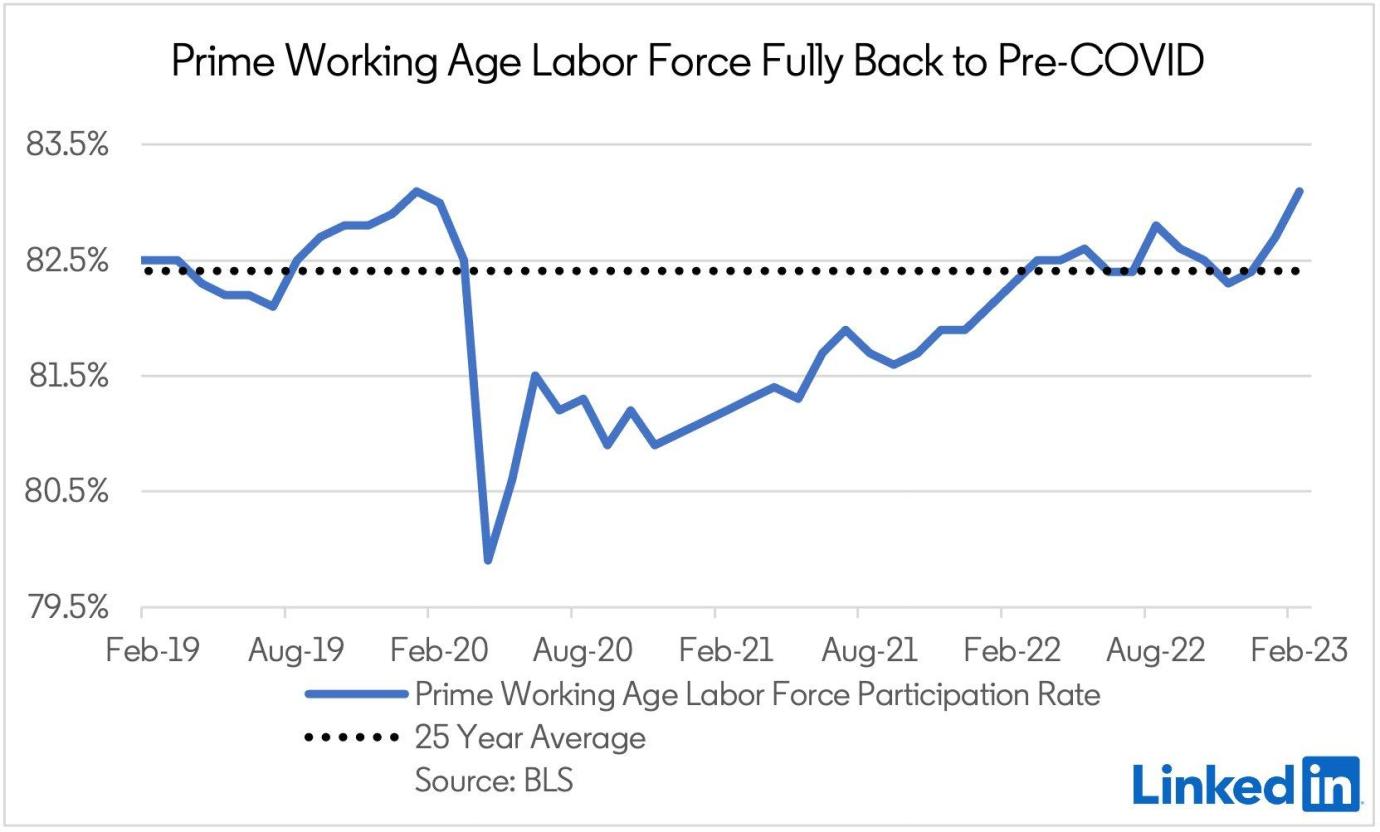

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.