Dear Capitolisters,

One of the most important critiques of industrial policy and other forms of economic planning is that the smartest plans proposed by the smartest people are rarely, if ever, what actually get implemented. In case after case, industrial policy plans sound good on paper and generate impressive results in various academic models. But they are ultimately distorted by politics, bureaucratic inertia (or incompetence), pre-existing policies, private or public resistance, or unanticipated market developments. A proposed policy’s results often look nothing like those in the technocrats’ dreams—and, often enough, undermine those dreams.

This problem is one of this newsletter’s running themes, and we’ve spent much of the last two-plus years documenting the carnage. Recent events surrounding U.S. electric vehicle subsidies compel me to revisit the subject.

About Those EV Plans

While I’m not totally sold on EVs’ environmental benefits, I’m also not an EV-hater. In my opinion, the latest models’ technology and styling look really, really cool, and—if I were a “car guy” (I’m not) and had a ton of money lying around (I don’t)—I’d totally be in line get one and have said so publicly on more than one occasion.

But liking a thing is, of course, a far cry from wanting the federal government to enact a Rube Goldbergian jobs plan covered in green paint. Let the market decide, folks.

Unfortunately, as we first discussed last August, the IRA (author’s note: I refuse to use its full name) did just that, handing American consumers a large subsidy for purchasing EVs, but with all sorts of industrial policy strings attached:

Expanded tax credits for electric vehicles (EVs) include unsurprising China-related restrictions but go a lot further than that. In particular, subsidies are available for only “clean vehicles” whose “final assembly” is in North America—meaning that EVs assembled in Europe, India, Japan, Korea, and plenty of other non-China countries wouldn’t qualify. Furthermore, the full $7,500 credit is available only for vehicles in which (1) a substantial (and increasing) share of battery “critical minerals” come from the U.S. or a free trade agreement country (again excluding Europe, Japan, India, China, and others) and (2) a substantial (and increasing) share of “battery components” are manufactured or assembled in North America.

Important additional limitations include obviously political caps on both the price (“MSRP,” including options) of qualifying EVs—$55,000 for cars and $80,000 for trucks and SUVs—and consumers’ annual incomes ($150,000 individual, $225,000 head of household, and $300,000 joint filer).

As thoroughly documented at the time, the myriad rules and limitations on the EV subsidies were necessary to win political support for the IRA, especially from lynchpin Sen. Joe Manchin. However, many subsidy supporters also claimed that this industrial policy would be great for the environment and the U.S. economy (by bolstering domestic EV/battery production and diluting China’s influence on the global EV supply chain). One can, of course, question whether all three things can really be true at the same time—if Manchin’s final terms were really that awesome, IRA champions would’ve already supported them—but the win-win-win claim has nevertheless been attached to the EV subsidies—by the White House, congressional Democrats, industrial policy supporters and others—since the summer.

Subsequent events, however, call those claims—and the subsidies’ effects—into serious doubt.

For starters, the subsidy restrictions set off an utterly predictable international firestorm among the non-China trading partners that produced EVs and batteries yet were mostly excluded from the scheme. The South Koreans, in particular, were incensed because their auto companies had committed to major new investments in the United States and Biden had personally promised that they’d benefit from the new U.S. EV policies. They openly called it a “betrayal” and questioned whether they’d still support Biden initiatives on China, semiconductors, and other key geopolitical areas. The Europeans, meanwhile, threatened to employ their own protectionism—tariffs, “Buy European” mandates, and targeted subsidies, etc.—to counter the U.S. subsidies. The typically mild-mannered Japanese also got into the act, suggesting that the subsidies might cause their automakers to rethink their U.S. investments, and that they’d also bring a World Trade Organization case against the (clearly WTO-inconsistent) local content conditions.

By November, things had gotten pretty heated:

Needless to say, the global environmental and economic harms of a tit-for-tat trade war among some of the United States’ closest allies—not to mention potential other geopolitical problems with China, Russia, or North Korea—would probably undermine some of the EV subsidies’ efficacy.

Other factors might do the same. As we discussed last time, the subsidies’ numerous conditions limited the current pool of eligible EVs, and inflation could shrink it further in the years ahead. According to the Wall Street Journal, in fact, the average EV is now priced well above the current car price cap: “The rising cost of lithium and other battery minerals have prompted car makers to raise prices, which could sap demand. The average price paid for an EV in the U.S. hit about $66,000 last summer, up from about $51,000 a year earlier, according to J.D. Power.” (The IRA doesn’t appear to index those values to inflation, and good luck amending the law to fix that issue now.) Toyota’s CEO also recently cautioned about the speed of EV proliferation, given supply chain and infrastructure limitations—some of which are, as the Journal’s Alysia Finley recently noted, retarded by other U.S. protectionism, industrial policy, and regulation:

Federal funds also come with many rules, including “buy America” procurement requirements, which demand that chargers consist of mostly U.S.-made components. New Jersey says these could “delay implementation by several years” since only a few manufacturers can currently meet them. New York also says it will be challenging to comply with the web of federal rules, including the National Environmental Policy Act, the Americans with Disabilities Act, the Uniform Relocation Assistance and Real Property Acquisition Policies Act of 1970, and a 1960 federal law that bars charging stations in rest areas.

Oh, and labor rules. The administration requires that electrical workers who install and maintain the stations be certified by the union-backed Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Training Program. New Mexico says much of the state lacks contractors that meet this mandate, which will reduce competition and increase costs.

Finally, and perhaps because of the first two things, the Treasury Department just released its initial guidance for subsidy eligibility, radically altering several of the conditions that seemed pretty darn clear in the law itself:

- Most important, Treasury has applied the $7,500 subsidy for “commercial vehicles”—which has none of the aforementioned limitations and was assumed to cover actual commercial vehicles—to vehicles leased to consumers. Thus, an auto dealer can receive the subsidy for any EV, regardless of price or where it’s made, and pass on some or all of it to any American consumer, regardless of his business or income. (Such subsidies are usually passed on.)

- Also, Treasury took a broad and novel view of “free trade agreement”—contrary again to the standard definition used in decades of U.S. policy and law—such that countries other than the 20 actual U.S. FTA partners could qualify for IRA subsidies for EVs with batteries that have the approved “critical minerals.”

- On the other hand, Treasury also limited its definition of “SUV” such that several popular brands marketed as SUVs but not meeting Treasury’s definition, including GM’s Cadillac Lyriq EV and Ford’s Mustang Mach-E, didn’t qualify for subsidies because their MSRPs exceeded $55,000. Other brands saw a weird bifurcation: Tesla’s popular five-seat Model Y isn’t heavy enough to be an “SUV” by government standards and thus doesn’t qualify for a subsidy because of its $65,990 MSRP. The exact same car, however, does qualify as a heavier, slightly more expensive seven-seater. The Volkswagen ID.4, meanwhile, isn’t an SUV when sold with two-wheel drive, but is an SUV with all-wheel drive.

If this wasn’t confusing enough already, these preliminary rules could change again when Treasury releases its final versions in March—a process that’s sure to keep K Street busy in the meantime.

Tellingly, the guy who drove (pun!) the IRA’s convoluted subsidy rules, Sen. Manchin, was aghast at Treasury’s interpretations, saying that they clearly violated the law’s (and his) economic nationalist intent and vowing to introduce new legislation “further clarifies the original intent of the law and prevents this dangerous interpretation from Treasury from moving forward.” (Not gonna happen.) For those keeping political score at home, neither of Sen. Manchin’s two big conditions for supporting the IRA—EV protectionism and permitting reform—has materialized.

Unintended Consequences

On the one hand, expanding the subsidies to cover more countries and vehicles might lessen international pressure and provide a slightly saner approach to U.S. environmental policy. As I’ve long said, to the extent that government policy is needed to accelerate the proliferation of EVs and other environmental goods, a relatively simple, non-discriminatory (i.e., no protectionism) consumer subsidy is a pretty good approach—especially when combined with supply-side reforms like lower trade barriers and streamlined domestic regulations.

However, that’s most definitely not what we got, and the “politically necessary” policy’s unintended consequences are becoming clear.

For example, Treasury’s interpretation of the “commercial vehicles” provision will surely encourage more Americans of all income levels to lease EVs, especially since they’ll have a far wider selection of vehicles to choose from. Indeed, the Journal’s editors noted last week that leasing was already popular: “An Experian report last February estimated that about 28 percent of new EVs are leased. Many EV drivers prefer leases because they expect battery technology to improve and their resale value to fall quickly.” We should expect those figures to increase in the months ahead, since dealers usually “pass on EV subsidies to their customers in order to lower the price of vehicles.”

A proliferation of EV leasing could have several unwelcome (or, at least, unintended) consequences. For starters, leasing a car is often a bad long-term financial decision, and it can actually be less environmentally friendly by encouraging more turnover and thus emissions-heavy production of new vehicles and parts. (Both conclusions depend, of course, on the specifics.) The elimination of any protectionist conditions, moreover, might not only benefit Chinese producers but also cause multinational automakers to rethink their much-touted U.S. investment plans—either out of fear of lower-priced import competition or simply to utilize existing non-U.S. supply chains. As one expert recently put it, “The bigger question going forward is whether the tax guidance alters foreign automakers’ investment in the U.S., with companies like Hyundai [whose Korean-made vehicles don’t qualify for the direct consumer subsidy] offering more vehicles for lease instead of investing in North American facilities.” Further depressing investment is the uncertainty of it all: If Treasury can define a free trade agreement one way today, it can define it another way tomorrow. (And don’t even get me started on what a Republican administration might do in 2025.)

The subsidy rules also could encourage Americans to buy or lease bigger, heavier, and more expensive vehicles, raising safety and environmental problems. As Harvard’s David Zipper just explained in The Atlantic, EVs are already much faster and heavier than their traditional automobile counterparts (and thus potentially more hazardous to other drivers and pedestrians):

=As large as gas-guzzling SUVs and trucks are, their electrified versions are even heftier due to the addition of huge batteries. The forthcoming electric Chevrolet Silverado EV, for example, will weigh about 8,000 pounds, 3,000 more than the current gas-powered version. And there will be a lot of these behemoths: A recent study from the U.S. Department of Energy shows that carmakers are rapidly shifting their EV lineups away from sedans and toward SUVs and trucks, just as they did earlier with gas-powered cars. … The danger rises further after accounting for EVs’ unprecedented power. “This sucker is quick!” President Joe Biden exclaimed after taking a Ford F-150 Lightning for a spin last year. He was right: The truck can accelerate from zero to 60 miles an hour in under four seconds, about a second faster than an F-150 running on gasoline.

Zipper adds that the heaviest EVs also aren’t very environmentally friendly:

Because they do not produce tailpipe emissions, electric cars are less polluting than otherwise identical gas-powered models. But EVs still create emissions in other ways, notably from the electricity required to build them and charge their batteries. Such energy needs rise dramatically for the biggest cars: According to the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, the 9,063-pound GMC Hummer EV contributes more emissions per mile than a gas-powered Chevrolet Malibu.

Worse yet, enormous EVs are compounding the global shortage of essential battery minerals such as cobalt, lithium, and nickel. That Hummer EV’s battery weighs as much as a Honda Civic, consuming precious material that could otherwise be used to build several electric-sedan batteries—or a few hundred e-bike batteries. One recent study found that electrifying SUVs could actually increase emissions by restricting the batteries available for smaller electric cars.

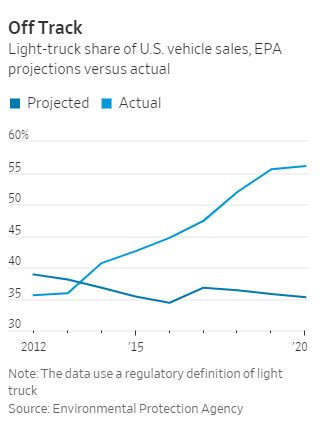

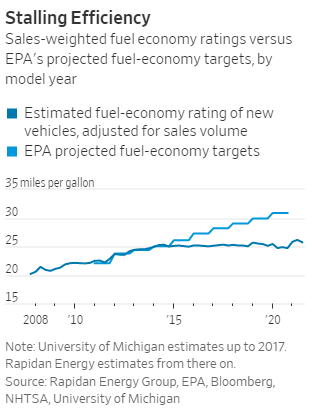

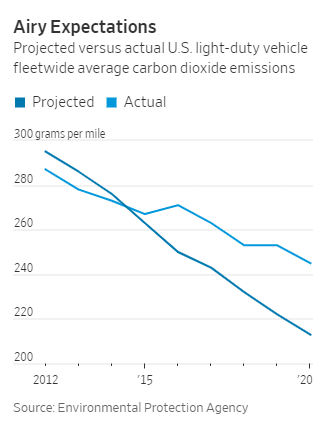

In this regard, we could see U.S. EV subsidies having a similar unintended effect on domestic transportation networks and the environment as CAFE regulations, whose rules are less stringent for larger automobiles and have thus been found to encourage automakers to make and sell trucks and SUVs and to have had a minimal (at best) environmental impact—rather important things the EPA’s technocrats apparently never saw coming.

In fact:

U.S. vehicles are among the least efficient globally: The average fuel consumption of newly sold U.S. light-duty vehicles, which include passenger cars and light trucks, exceeds the world’s average by 21% and Europe’s by 46%, according to the International Energy Agency. CAFE hasn’t bent the curve in absolute terms either. Carbon dioxide emissions from motor gasoline (excluding ethanol) were 23% higher in 2019 than in 1980 and the U.S. transportation sector’s motor gasoline consumption has risen by 39% over the same period.

As higher EV price caps for SUVs encourage, like CAFE regs, SUV production and consumption, might the subsidies have a similar effect? Sure seems so to me.

It’s not even clear that the Treasury finagling will satisfy disgruntled U.S. trading partners and stave off future disputes or more bad, beggar-thy-neighbor economic policy. Shortly after Treasury released the preliminary rules, for example, the European Commission issued a press release welcoming the lease subsidy rules that will benefit European producers. But it also stressed that the EU wants similar treatment for the purchase subsidies and remains upset about them: “This scheme remains of concern to the EU, as it contains discriminatory provisions which de facto exclude EU companies from benefiting. Discriminating against EU produced clean vehicles and inputs violates international trade law and unfairly disadvantages EU companies on the US market, reduces the choices available to US consumers and ultimately reduces the climate effectiveness of this green subsidy.” Meanwhile, the French still seem poised to press ahead with their green protectionism plans, despite Treasury’s changes. South Korea’s environment ministry, meanwhile, “has reportedly informed carmakers that domestic subsidies for electric vehicles could be limited to firms which run their own service centres in the country, excluding most foreign companies.”

The ‘Art of the Possible’ Can Be Really Ugly

The EV subsidies are a classic example of the reality of American industrial policy. It isn’t implemented in a vacuum by unbiased technocrats; it’s implemented in the U.S. political system, with everything—inefficient and porky legislation riders, unpredictable implementation, cost overruns, etc.—that that entails. And, as one market observer put it to Bloomberg, that’s a particular problem for the IRA: “This is what happens when legislation does not go through regular order and you don’t have a committee looking at all the provisions,” he said, referring to the fact that “[t]he bill was largely crafted behind closed doors between Manchin and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer.”

And this is what we got.

U.S. industrial policy also affects global players driven by their own domestic political and economic concerns, and the spigot of tit-for-tat protectionism and subsidization is difficult to turn off once it’s on. As The Economist recently noted about our impending “global subsidy race,” these lessons were learned decades ago and motivated not only the creation of global trade rules to discipline nations’ industrial policies, but also significant skepticism regarding its ultimate efficacy. Unfortunately, they add, “[i]t may take hundreds of billions of dollars to relearn why America was once an opponent, not an advocate, of subsidies.” And, given today’s political climate, maybe not even then.

As we discussed back in August, private investment in and demand for environmentally friendly technologies—including EVs and batteries—was already booming before the IRA became law. This EV investment—or, at least, related public announcements—probably accelerated in the wake of the IRA, which provided “extra carrots for carmakers already plotting ways to ‘onshore’ more of their supply chain.” But the cost of those “carrots” may prove to be high and will go even higher if trade relations go sideways or announced investment plans change.

Defenders of bungled economic planning always say that politics is the art of the possible, but they rarely seem willing to ponder whether the “possible” is actually worse than the status quo. It seems we’ll again find out.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.