Dear Capitolisters,

Every once in a while, I’ll stop chasing news cycles and instead dig into lesser-known areas of U.S. policy that deserve more attention. And so today we’re going to talk about “dumping”—a terrible-sounding word used by a lot of politicians and domestic interest groups (manufacturers, unions, etc.), usually in reference to some dastardly foreign imports they’re trying to block. But if you look at the actual, legal definition of “dumping”—and the history of U.S. anti-dumping law and policy—you’ll quickly realize that our most widely used “unfair trade” law actually has little to do with “unfair trade” at all, and almost everything to do with naked, costly protectionism. It also provides a cautionary tale for U.S. policy proposals that could establish similar systems today.

Rhetoric vs. Reality

Like a lot of protectionist policies in the United States, the U.S. anti-dumping law dates back more than a century and has expanded far beyond its original scope and intent. As Dartmouth’s Doug Irwin explains in his book, Clashing Over Commerce, the original Antidumping Act of 1916 was intended to discipline anti-competitive “predatory pricing”: In particular, it “made it illegal to sell imported goods at prices substantially lower than the market value in the exporting country ‘with the intent of destroying or injuring an industry in the United States.’” However, because proving foreign exporters’ “predatory intent” in U.S. courts was difficult and time-consuming, the law was rarely used. So Congress, naturally, went back to the drawing board a few years later and, in the Antidumping Act of 1921, “changed matters considerably.”

Under this new version, which (along with the Tariff Act of 1930) is the foundation for today’s anti-dumping law, there is no “predatory intent” requirement; AD cases moved from the courts to the bureaucracy; and AD duties simply police price discrimination. Thus, the treasury secretary could impose anti-dumping duties on imports if an investigation determined that 1) they were sold in the United States at less than “fair value” (i.e., the price charged by the exporter in its home market) and 2) were injuring the U.S. industry making the same product. As Irwin notes, “a foreign exporter charging a lower price on its sales in the United States than in its own home market could be found guilty of dumping”—regardless of the exporters’ intent or any other circumstances. The difference between that home market price (say, $110 per widget) and the U.S. export price (say, $100 per widget) is the “dumping margin,” which is then converted to a final AD duty rate applied to subject imports by dividing the margin over the company’s U.S. sales: In our very simple example, (110-100)/100 equalsa 10 percent tariff—on top of any normal tariff the U.S. already applies on the product.

Thus arises the first problem with the anti-dumping law and common allegations of “dumping”: Price discrimination alone is a horrible proxy for any sort of “unfair” or anticompetitive trading practice, including the most common ones today linked to “dumping”—i.e., predatory pricing or closed (“sanctuary”) home markets. As my Cato colleagues have written repeatedly, there are plenty of legitimate, commercial reasons why a company might charge a higher price in its home market than in an export market, and this kind of price discrimination happens every day in the United States—in international or interstate trade—in all sorts of industries. It’s totally normal stuff, yet it’s dutiable under the anti-dumping law.

Subsequent revisions to the law define “dumping” as also occurring when a foreign company sells in the U.S. below its cost of production. This is closer to something that might indicate “unfair” trade (e.g., foreign subsidies or sanctuary markets), but there are still many normal (non-predatory) reasons for why below-cost sales might occur: For example, temporary “loss-leader” sales in an important new market or for a new, untested product; financially weak companies selling off assets to pay creditors instead of declaring bankruptcy; severe recessions or currency problems in home markets; and so on. Economically, moreover, this type of “predatory” behavior is rarely—if ever—effective in killing off competitors and establishing market dominance. (See this Don Boudreaux essay for more.)

Regardless, the U.S. government has itself acknowledged that “The antidumping rules are not intended as a remedy for predatory pricing practices of firms or as a remedy for any other private anticompetitive practices typically condemned by competition laws.” So that settles that.

So why, then, does the U.S. anti-dumping law even exist? As my former Cato colleague Dan Ikenson and others have explained, it was a simple political compromise: Developed countries—particularly the United States—agreed to lower their tariffs if they maintained the right to impose “trade remedies” restrictions on certain imports, i.e., anti-dumping duties and those targeting subsidies (“countervailing duties” or “CVDs”) and global import surges (temporary “safeguards”). In the United States, Ikenson details how this compromise was primarily about placating Congress during past free trade agreement negotiations, particularly at the World Trade Organization (WTO) and its predecessor the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT):

At the founding of the GATT, U.S. negotiators insisted that language permitting the use of antidumping be included. A view widely held—or at least the excuse given—by them at the time was that antidumping rules made deeper trade liberalization possible because they assured Congress that fallback contingencies were available if general tariff cutting exposed domestic industries to too much competition. Without antidumping, the argument went, Congress might not support general tariff liberalization.

Evidence that Congress was serious about preserving and protecting the U.S. antidumping law emerged during debate in the Kennedy Round over the implementation of this legislation. During the round, modest changes to domestic antidumping administration had been agreed upon. But Congress refused to accept the agreement’s disciplines on domestic antidumping laws and ultimately carved out those changes from being implemented in the legislation.

Thus, the final WTO agreements both codify non-discriminatory tariff cuts and permit discriminatory trade remedies, subject to certain substantive and procedural disciplines enshrined therein.

But That Was Then …

At one time, this compromise may have been reasonable: According to Irwin, for example, anti-dumping cases were rare in the years leading up to and following the GATT’s entry into force in 1947: “from 1934 to 1954, there were only seven findings of dumping” in the United States. And only a few countries used them at all, while even fewer used CVDs.

Since then, however, anti-dumping has turned into a classic “Frankenstein’s Monster” economic policy, smashing trade villages around the world. Most notably, the U.S. Congress has repeatedly rewritten the law to make it easier to find “dumping” or “injury” where these requirements wouldn’t have previously existed. These changes include:

-

Transferring jurisdiction for AD/CVD investigations from Treasury (which looks after the entire U.S. economy) to the Commerce Department (which promotes the narrow interests of U.S. manufacturers).

-

Implementing numerous methodological changes since the 1970s that allowed Commerce to inflate dumping margins—and thus final duty rates—by essentially ignoring even the watered-down “price comparison” objective. Today, for example, Commerce can disregard the financial data foreign exporters submit for sales, production costs, profits, and other items, and it can instead “construct” prices using partial data, “adjusted” figures (biased against the foreigners, of course), or even data from other countries that aren’t under investigation. The last bit of ridiculousness used to apply only to imports from China and other “non-market economies” (basically, Vietnam), but changes snuck into 2015 legislation let Commerce today apply similar approaches for imports from obvious “market economies” like South Korea. The result: creating “dumping” out of thin air.

-

Relaxing the standards by which the International Trade Commission (ITC) can determine whether imports Commerce finds to be dumped or subsidized are “injuring” the domestic industry.

-

Establishing a convoluted “retrospective” system, under which final duties imposed on imports are calculated a year or more after those goods have entered the country—an additional, non-tariff trade barrier that, per GAO and U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, confounds U.S. duty collection efforts.

-

Rejecting amendments to the law that would allow U.S. agencies to consider the “public interest” (e.g., consumers, broader national economic or foreign policy interests, or emergency situations) or to apply a “lesser duty” where doing so would remedy the “injury” suffered by the domestic producers. Jurisdictions like Canada and the EU apply these common-sense rules, which sure would’ve been useful when the U.S. applied – in the middle of a global pandemic – AD/CVDs on lumber, fertilizer, intermodal chassis, and other critical goods.

As a result of these changes, past studies have repeatedly shown that U.S. anti-dumping actions rarely (almost never) target anything even remotely close to anti-competitive or predatory behavior by foreign exporters or “unfair” policies by their governments. In many cases, “dumping” has been found where foreign companies were actually selling in the U.S. well above the prices in their home markets. So it often doesn’t even target price discrimination!

As I wrote a few years ago, Congress has done similar things with the CVD law—including by changing the definition of a “subsidy” to allow for duties on softwood lumber back in the 1980s. Today’s CVD law isn’t as problematic as the AD law, but it’s also used much less frequently—about 75 percent of all U.S. cases are AD cases.

Meanwhile, decades of congressional pressure and industry lobbying have resulted in agencies that have been effectively “captured” by a handful of politically powerful companies and unions, especially the steel industry. For example–

According to interviews with former congressional and Commerce Department staff conducted by the Office of the Inspector General: “This [pro-steel industry] bias is illustrated by the actions of career Commerce Department officials through whom must pass all Department of Commerce [antidumping] determinations in steel cases. The members and staff of the congressional Steel Caucus meet with them regularly to discuss ongoing antidumping and countervailing duty proceedings pending before the Department of Commerce. At some of these meetings, these officials have shared advance draft investigation results with the congressional Steel Caucus well before they were announced in final form, allowing the Steel Caucus to “comment” on them. Time and again high level officials within the agency have exerted pressure on lower level Department of Commerce staff conducting investigations of foreign steel producers to rerun calculations and alter methodologies, resulting in increased AD/CVD tariffs.

As of last week, almost half (311 of 649) of all U.S. AD/CVD orders in place were on iron and steel products—and it’s easy to see why.

Commerce has also resorted more often to using “facts available” data or the punitive “adverse facts available” (AFA), which again leads to higher duties. As I wrote last year, “lawyers report (quietly, of course) that Commerce’s AFA decisions are increasingly abusive—for example, by invoking AFA after establishing unreasonably short and rigid deadlines for providing mountains of information (that often must be translated); by applying … for minor and unintentional technical errors; or by throwing out all evidence submitted by foreign respondents (‘total AFA’) where only a small amount of data is in question.”

In other words, even where the rules might be facially neutral, the “refs” are making sure the game is rigged.

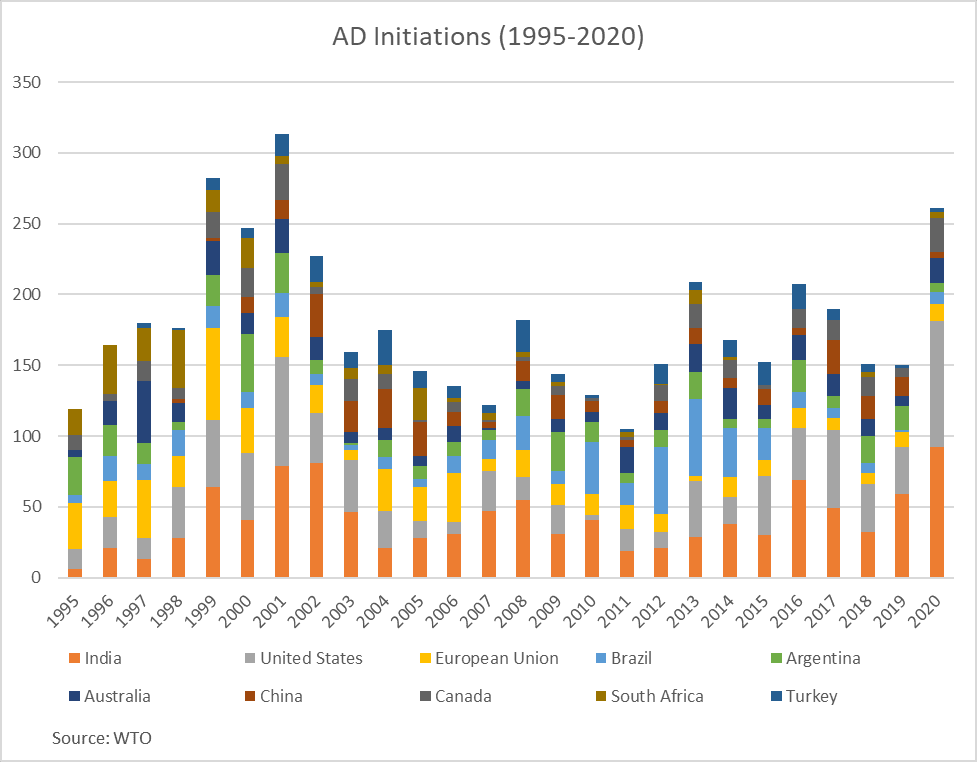

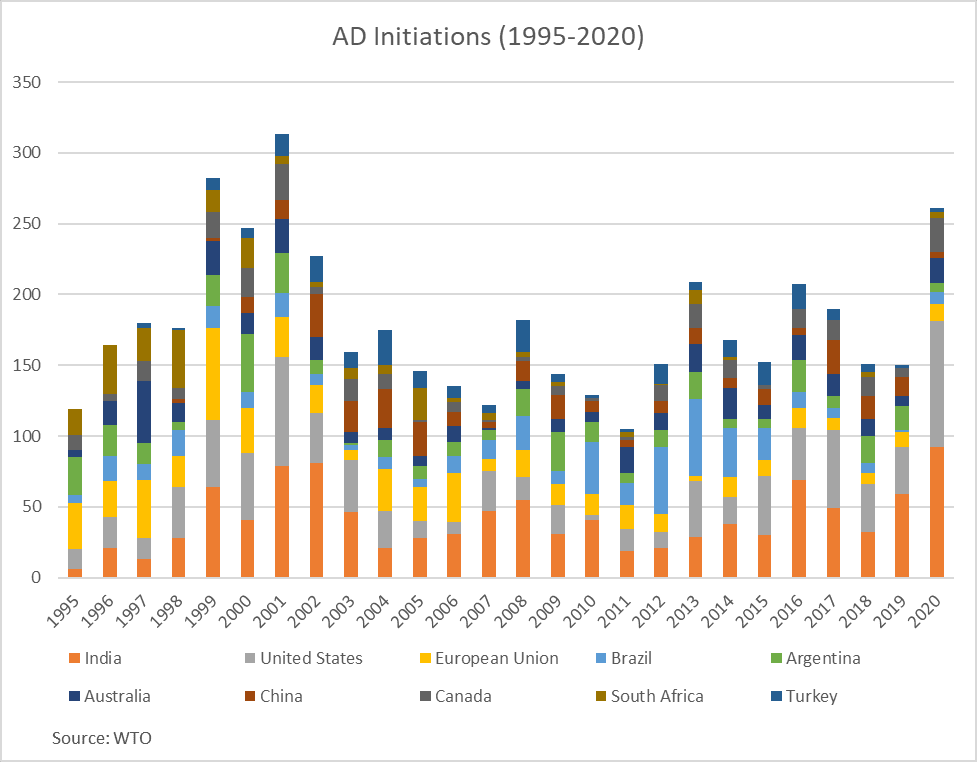

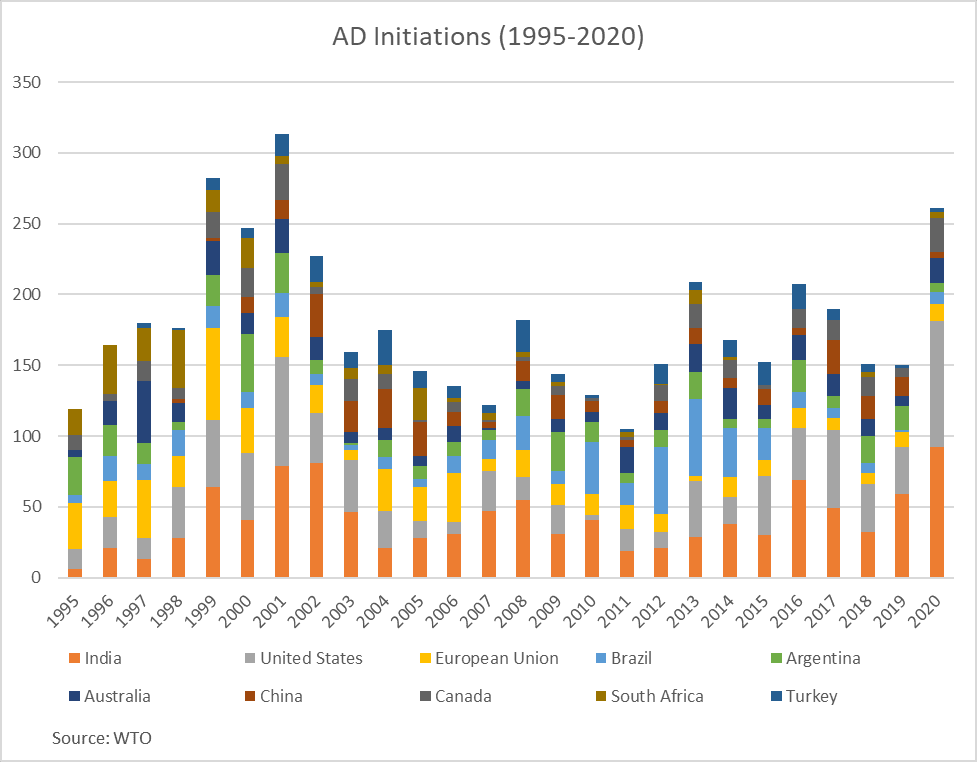

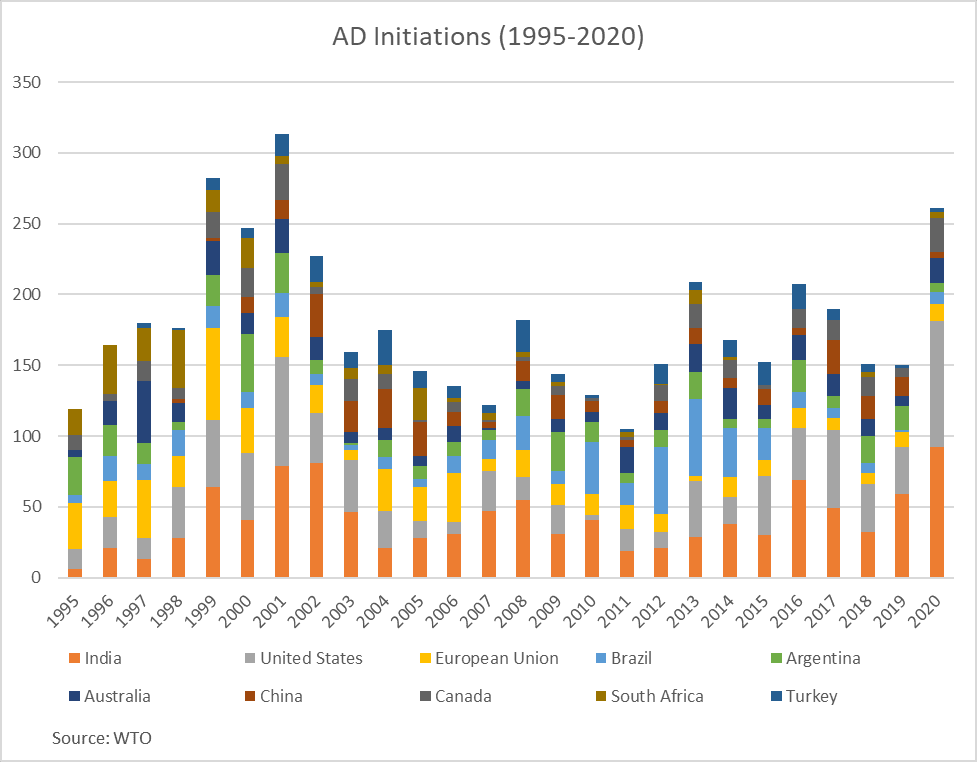

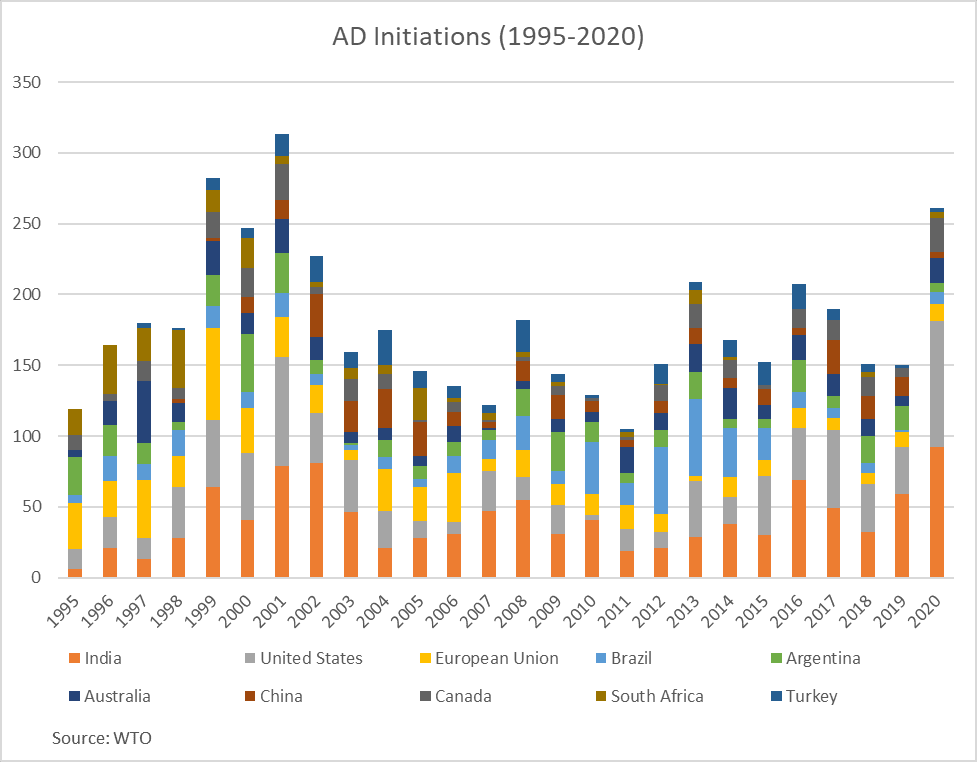

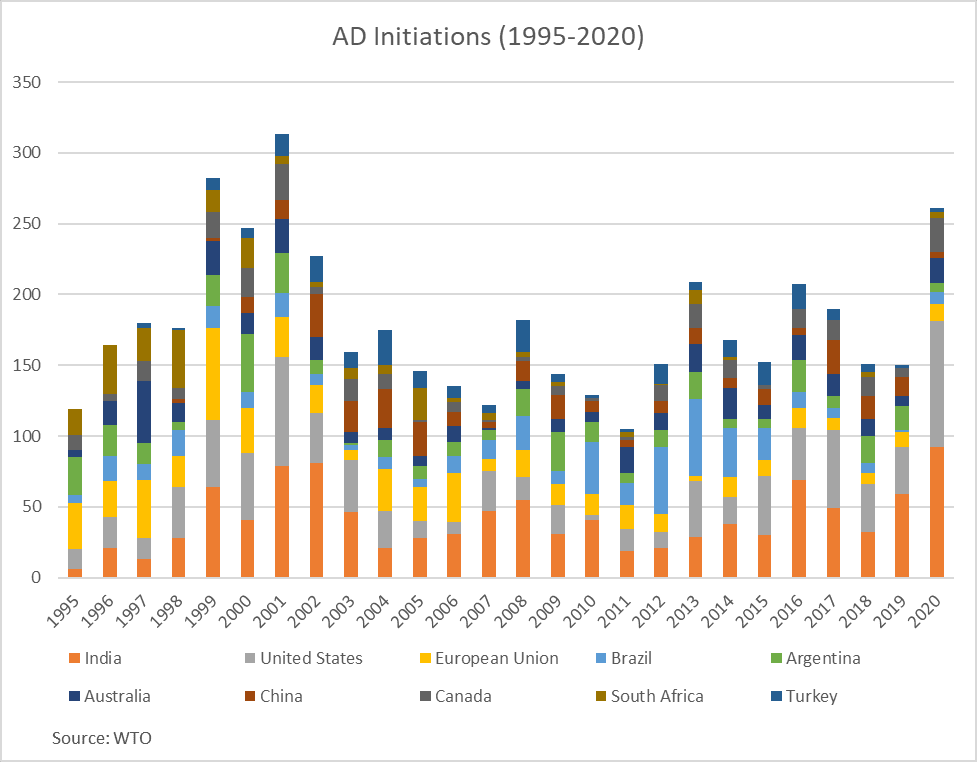

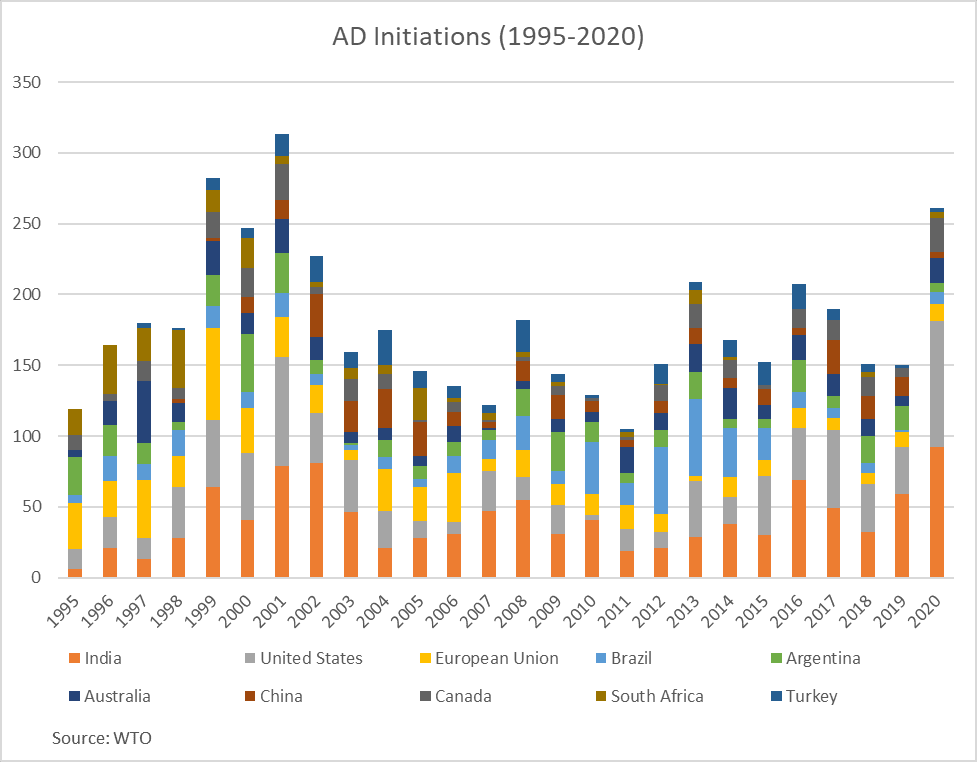

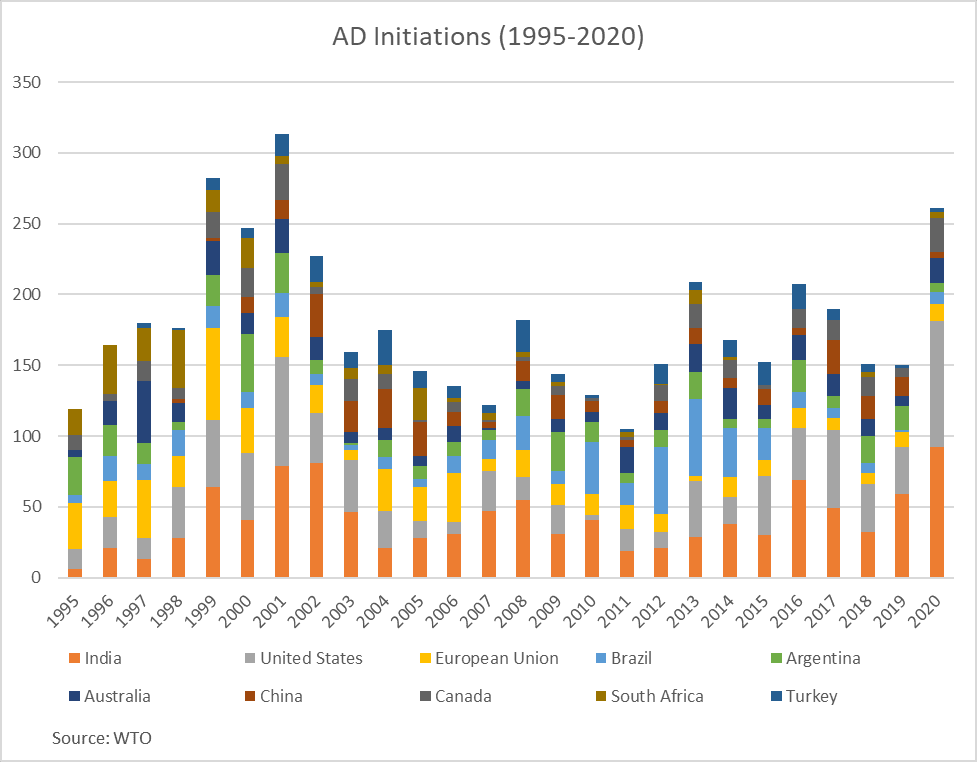

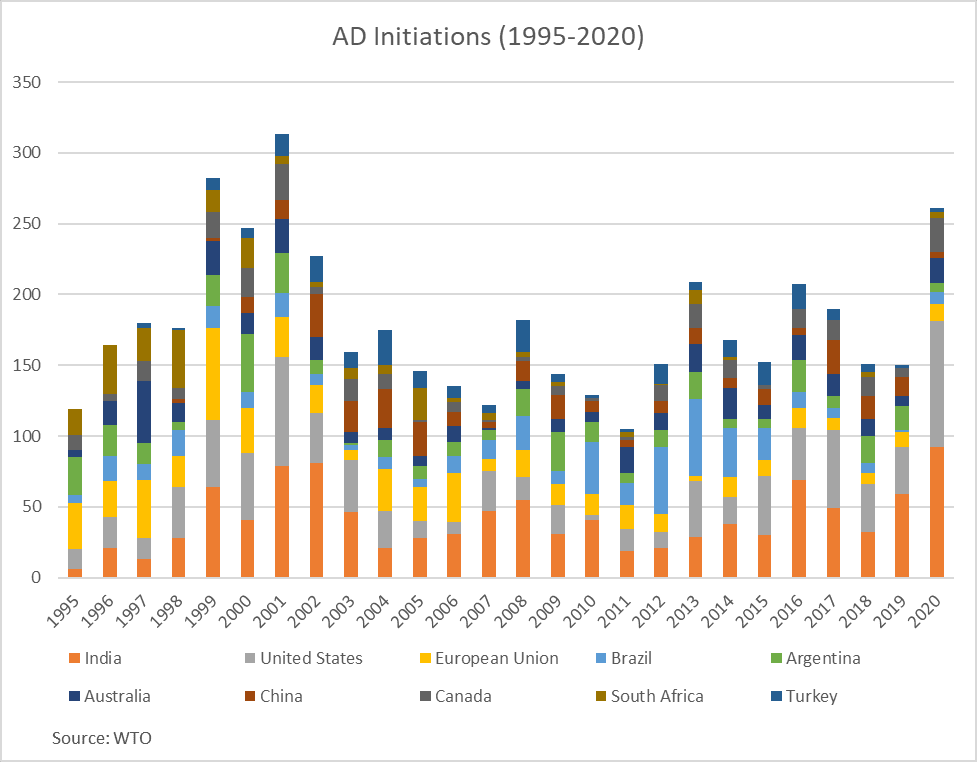

All of these developments have caused the United States’ use of anti-dumping measures to skyrocket since the law’s early days. As noted above, the U.S. now has almost 650 AD/CVD orders in place—an increase of about 300 since just 2016 and a far cry from those seven in the 1940s and 1950s. About a third of these duties target imports from China. The United States is also the world’s top user of CVD actions and a close second to India in initiating (much more common) anti-dumping cases since 1995:

Counting the Costs

Unsurprisingly, independent studies routinely show that these trade actions have imposed significant harms on the U.S. economy while failing to protect petitioning companies or workers over the long term. (Tellingly, the ITC’s periodic reports on “the economic effects of significant import restraints” don’t consider AD/CVD actions because the U.S. trade representative expressly excluded them from its original request.)

My 2017 paper has a lot of the economic history of U.S. trade remedies, but a few subsequent papers warrant mention. First, a July 2020 working paper from economists Alessandro Barattieri & Matteo Cacciatore examined the hundreds of U.S. AD/CVD actions initiated between 1994 and 2015 and found that duties 1) were concentrated in industrial inputs, especially steel; 2) depressed employment in downstream U.S. industries (e.g., steel‐using manufacturers); but 3) provided no long‐term benefit for jobs in the protected, upstream industries (e.g., steelmakers).

In a January 2021 paper, a trio of economists examined anti-dumping measures on Chinese imports imposed between 1988 and 2016 and found that these duties 1) increased substantially over the period examined, and particularly during the height of the “China Shock” in the 2000s; 2) had large, negative effects (increased production costs and decreased employment, wages, sales, and investment) on downstream industries; but again 3) had no significant effect on blue‐collar jobs, wages, or sales in the protected industries. They estimate that the antidumping measures cost approximately 1.85 million U.S. jobs between 1988 and 2016, primarily in blue‐collar services industries:

They further find that duties were often politically motivated, with protection more likely when petitioning companies or workers were in U.S. swing states. (Separate research shows that the only folks who make out well from an AD/CVD case seem to be the protected companies’ CEOs.)

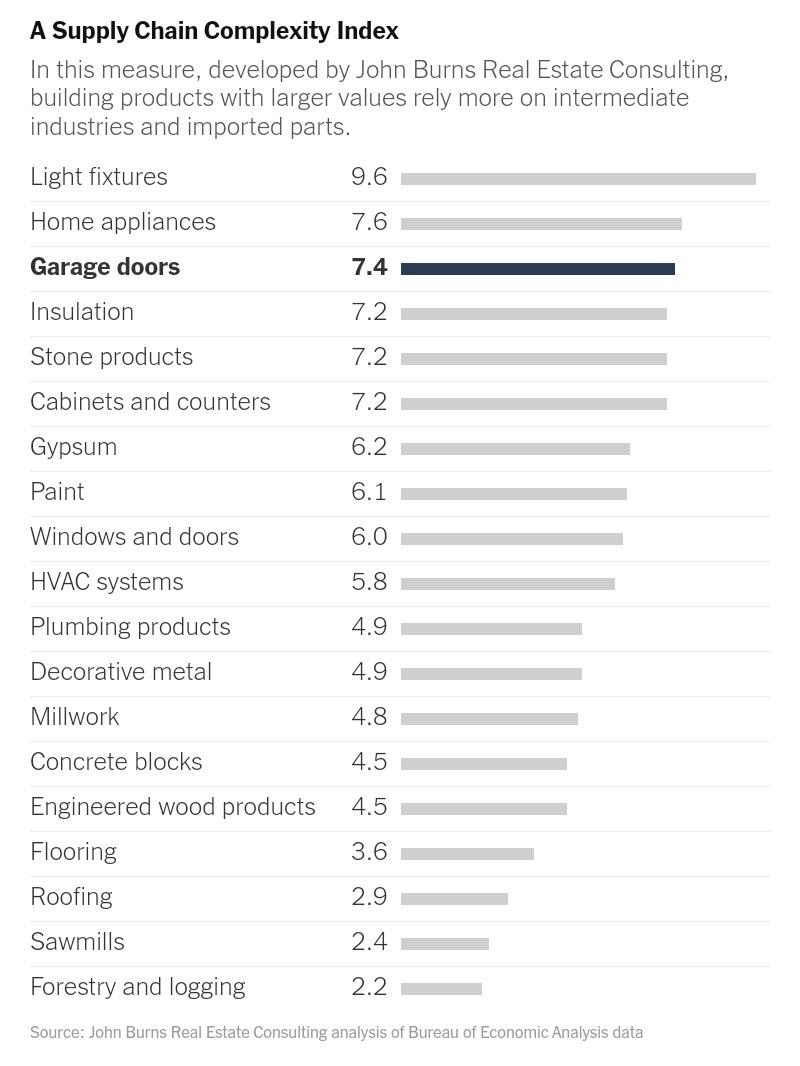

And just last week, Barattieri and Cacciatore released (with Cato’s help) a new version of their 2020 paper targeting just construction materials and U.S. home prices, both of which have increased dramatically in recent years. They find that 1) the United States has imposed numerous AD/CVD measures on a wide range of construction inputs, with median duty rates of 28 to 134 percent (Table 1 below); and 2) a U.S. trade remedy action causes domestic construction material prices to increase significantly and stay that way for a year or more (Figures 2 and 3).

The authors thus conclude:

Tariffs imposed by the U.S. government on materials used by the domestic construction sector cause a significant increase in the cost of those goods. These results suggest that lifting trade restrictions on intermediate inputs could help dampen recent increases in U.S. construction material costs. Addressing the ultimate impact of these trade barriers on skyrocketing U.S. housing prices is beyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, U.S. homebuilders report that they often pass on higher material costs to homebuyers, and previous research notes that many homes in the United States are priced close to their construction cost, of which materials (e.g., lumber) are a significant part. Our results therefore suggest that U.S. trade barriers affect home prices, at least in certain areas, and that this connection is an important avenue for future analysis and research.

Right on cue, the U.S. has now initiated new AD/CVD cases against nails from five different countries—a case that joins current duties on nails from China and several other countries. Good thing U.S. homebuilders don’t need those!

U.S. trade remedies policy also imposes other harms. Most notably, the tricks that the United States has for years employed when operating its trade remedies system have caught on in other countries, particularly developing ones like China, and are now used against American exporters in these rapidly growing markets. Adding insult to injury, the United States has vehemently resisted efforts to reform its abusive trade remedies practices– even after losing repeated WTO dispute settlement cases on the same issue!—or to engage in any WTO negotiations tightening the rules for applying these measures. As a result of this intransigence, major WTO negotiations have stalled out (including ones that might lead to better disciplines on Chinese transgressions); the entire dispute settlement system is on ice (blocked by the United States because it disagrees with past interpretations of trade remedies rules); U.S. exporters have little recourse for foreign trade remedies abuses targeting them; and—when combined with persistent U.S. farm subsidies—the United States has little, if any, high ground in global trade talks at the WTO or elsewhere.

Trade remedies cases have also been found to increase market power for domestic companies—something U.S. steel consumers know all too well—and to raise serious constitutional questions about whether Congress has delegated too much of its tariff powers to the relevant administering agencies. And instead of reforming these laws, Congress—in the America COMPETES Act the House just passed, for example—is looking to make them even worse.

Of course they are.

Broader Lessons

As you can probably tell, this type of stuff gets me pretty lathered up—a relic, I guess, of having spent a frustrating decade-plus litigating AD/CVD cases here. But while anti-dumping law and policy might seem arcane or boring for some of you, it still provides a teachable lesson for numerous other policies—including some in the aforementioned COMPETES Act—now under consideration. Most obviously, common claims that we need new American protectionism because we’ve for too long embraced “unfettered free trade” and “played by the rules” (or whatever) become patently ridiculous when U.S. AD/CVD policy is considered. Furthermore, new proposals for U.S. industrial policy—especially but not only those relating to trade—need to grapple more fully with the long and sordid history of the U.S. antidumping law (and others like it), which started out policing real anticompetitive behavior a century ago and has since slowly morphed into little more than a quiet means of using captured agencies to deliver economic rents to favored political constituencies under the guise of policing “unfair” trade. Indeed, as I wrote last year:

Commerce’s behavior—and the laws authorizing it — also serves as a warning about the perils of U.S. protectionism and industrial policy: even in systems administered by a “neutral” bureaucratic arbiter and designed to be insulated from the political process, the administering agency can become “captured” by powerful domestic interests and the rules can be corrupted by politicians eager to reward attentive constituents with highly technical changes hidden from the vast majority of the American public.

U.S. anti-dumping policy also urges serious caution when considering new proposals to empower a bureaucratic agency to impose new penalties (taxes, fees, etc.) or subsidies based on highly complex determinations and calculations. For example, many folks (including some in Congress) have proposed that any U.S. carbon tax system include a “border adjustment”(essentially a tariff) to be applied on imports according to their “carbon intensity” (basically equivalent to the amount of carbon regulation in their home markets). The idea, which has some theoretical basis, is that taxes are needed to offset possible competitive advantages exporters gain from being in lightly-regulated markets (and to encourage those markets to adopt stricter carbon regulation).

In reality, however, our experience with U.S. antidumping law shows how a mechanism authorizing Commerce or another U.S. agency to police “carbon dumping” (or whatever) is rife with potential problems. And what might even start out as a legitimate proceeding could easily morph into yet another economy-weakening vehicle for rent-seeking. Maybe it won’t, but we should at the very least be aware of these pitfalls. Most advocates aren’t.

Or, in the U.S. steel industry’s case at least, they pretend not to be.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.