Longtime readers know that I’m somewhat obsessed with declinism, the belief that America is in a state of serious, perhaps terminal national and cultural decline. Declinism is the father of catastrophism, the political idea that the nation is so close to the precipice that it’s one election away from extinction. In many ways, if you’re going to understand the appeal of the new right or the populist right, you have to understand the deeply felt conviction that America is on the brink.

My theory—articulated at book length—is quite different. Declinism and catastrophism are themselves far more dangerous to our republic than the trends or ideas that declinists decry. False claims of an emergency or of corruption or tyranny can make people respond as if they’re true. January 6 was a prime example of the damage that can result.

In fact, there is a lot of evidence that social conservative panic is particularly misplaced. Multiple vitally important indicators of family health have been improving, and many of those indicators have been improving for some time. The divorce rate has hit a 50 year low. Abortion is way down. Teenage pregnancy is down. Despite a hopefully temporary increase in 2020, violent crime is way down. Young adults have fewer sex partners. The percentage of children living with both parents has stabilized and even slightly increased.

It turns out that, say, thirty years ago—when our memories tell us America was more culturally conservative politically—many social indicators that social conservatives value the most were substantially worse than they are today. Yes, on a number of fronts Americans have more culturally progressive beliefs than they did, say, in 1990, yet by the tens of millions, they have more culturally conservative lifestyles than the generation before. It’s a phenomenon somewhat clumsily called “believing blue and living red.”

All that’s a long preface to my real point. There is one arena where declinists make a compelling argument. They rightly point to a trend that, over time, could fundamentally alter our living standards, transform our economies, and potentially even (further) destabilize our democracy. That trend is the declining American birth rate.

No, wait. It’s the declining western birth rate.

No, wait. It’s the declining birth rate in virtually every liberal democracy in the world.

Wait, that’s still not it. It’s the declining birth rate in virtually every industrialized, moderately wealthy country in the world.

America’s decline mirrors the world’s decline, and nobody really knows what to do.

The bottom line is that as our world gets more prosperous, and as even the least developed countries grow more economically advanced, families respond by having fewer babies. That’s not so much of an issue when they still have enough babies to sustain populations and thus sustain economies. It’s even potentially manageable if a nation is a desirable enough destination that it can attract enough immigrants to grow its population and its economy. But there is a point at which a declining birth rate means national decline in arguably the most tangible way possible.

For example, read yesterday’s Wall Street Journal for a poignant, deeply reported story about Latvia’s profound population loss. The raw numbers are sobering:

Since joining the European Union, with its open borders and freedom to work anywhere in the bloc, in 2004, Latvia has lost 17% of its population; only neighboring Lithuania has lost more. The working-age population has fallen 23% over the same period.

Last year, Latvia recorded its lowest number of births in a century and the sharpest population drop in the EU, at 0.8%. This first half of 2021 was worse, with twice as many deaths as births.

I’ve been lurking around the birth rate debate for years, reading the literature, listening to the podcasts, and I’ve been struck by the extent to which the world is facing a massive civilizational shift—one for which politics provides few answers. Not that people don’t think there are political explanations. They feel like they know who (or what) to blame:

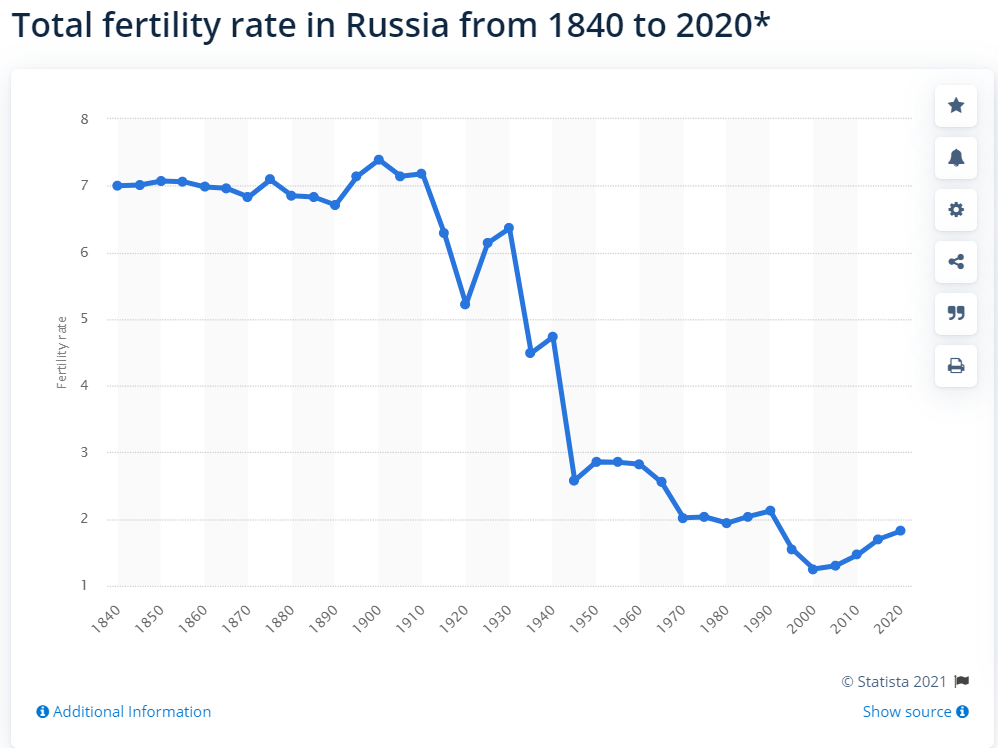

But it’s not that easy. Birth rates have decreased in liberal and authoritarian societies and in capitalist and communist economies. Take Russia (and the Soviet Union). Birth rates started dropping during the Czars, dropped the most under communist control, and then dipped a bit more after the Soviet government fell:

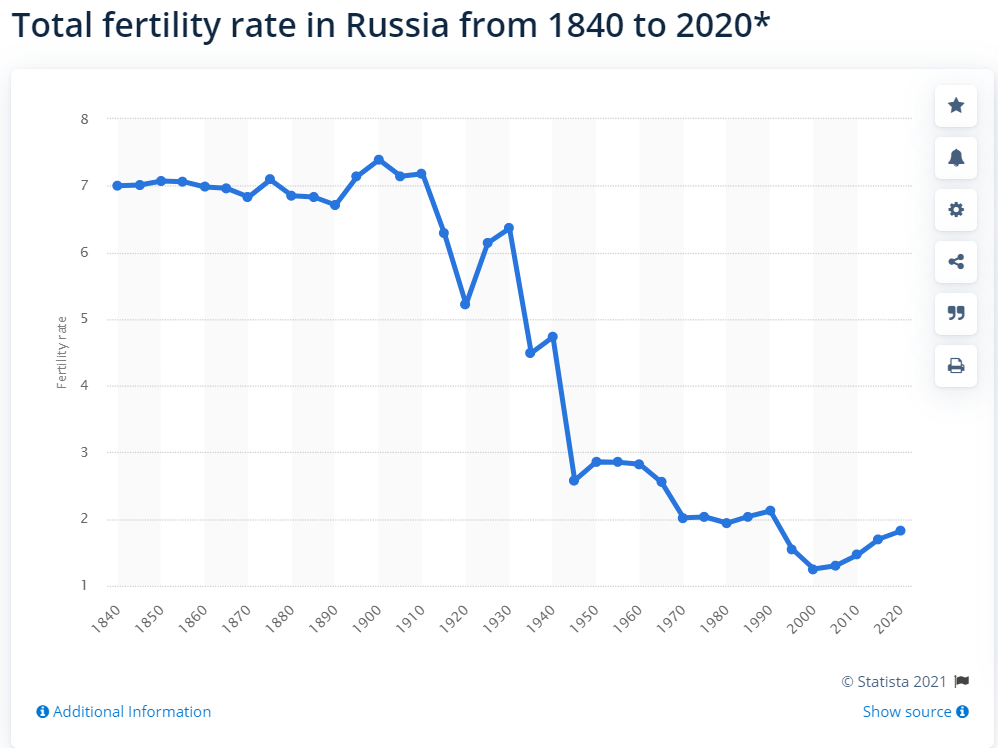

Compare that to the chart for the United States (and see if you can spot the baby boom):

Those two very different countries demonstrate the same long-term trend. Note too that birth rate declines easily predate the advent of widespread contraception. Lest you think I’m still cherry-picking, here’s the world rate since 1960, courtesy the World Bank (the link also takes you to fertility rates for every country on the globe).

When economies modernize, the birth rate declines. It’s clear that virtually every kind of world culture has fewer babies the more prosperous it becomes, with different cultures seemingly settling into different (low) baselines. Is that all individualism or liberalism? Not unless you define the choice to have fewer children as inherently individualistic, an expansion of the term that renders it meaningless.

Further, it’s also clear that governments haven’t really figured out how to use policy to materially reverse those long-term declines. In its story about Latvia, the Journal accurately said turning around a “demographic slide” has “historically proven all but impossible.

Nations with generous family leave policies still have low birth rates. Places that pay parents to have kids have low birth rates. Even large-scale efforts in authoritarian countries often have the most modest goals (Putin’s Russia has expanded “maternity capital payments” in an effort to increase the birth rate from 1.5 to 1.7 children per woman).

I am not saying policy does not matter at all. I strongly believe that we should do what we reasonably can to make family formation easier. Not because there exists a magic bullet to reverse national (or global trends), but because healthy families (of whatever size) contribute immensely to human flourishing.

At the same time, it’s important to note that a large family is not always a good family. The desire to have fewer children is not inherently selfish, and having many children is not inherently virtuous. There are multiple rational and even virtuous reasons why parents have chosen to have fewer children.

Moreover, it’s vital to stake out the ground that liberalism is not the same thing as individualism (or selfishness). A liberal society contains individualists, to be sure, but it also reserves room and protects space for those who are deeply communitarian, rooted in tradition, and committed to civic associations. And indeed, those who value large, robust, and prosperous families are likely to continue to be most at home in liberal societies, especially those societies that protect the liberty and autonomy of religious communities (which often have higher birth rates than their secular counterparts).

But there’s also a larger point. It is often difficult to discern which social developments are the result of titanic, tidal cultural and technological forces that no government can arrest, versus the product of much more temporary trends that react well to better policy, improved political leadership, or shifting cultural mores.

To the extent, however, that there is a worthwhile, arguably attainable policy goal, it might be in reducing the gap between the number of children families truly want, versus the number of children they actually have. For example, recent data indicates that American women say they want 2.7 children on average. They have closer to 1.8.

Frankly, I’m a bit skeptical about that data. Why? Because of trade-offs. I’ll let Lyman Stone explain. This is an excerpt from his recent, excellent discussion on Jane Coaston’s New York Times podcast:

Values change [and] that leads to a behavioral change. And the argument that I and a co-author make is that a big part of it is people changing their source of meaning-making towards the workplace and the career. You really derive value from it. It’s really what makes you who you are. And that this shift, we think, is pretty significant and that it leads to lower fertility and that it leads to lower accomplishment even of desired fertility. Because when people face trade-offs, if they get a lot of meaning out of this other thing and they aren’t sure how much meaning they’ll really get out of a child, even if they desire it, we think that this is one of the dynamics at play.

That’s exactly right. I think when many people hear the question, “How many kids would you like?” they interpret it as, “As one part of your ideal family picture (which includes meaningful careers, a certain standard of living, the time to invest in children, etc.), how many kids would you like?”

There is absolutely no way a government can create an economy that eradicates trade-offs. Even programs that are designed to ease family formation can, perversely enough, decrease fertility. In 2019, a paper studying the effects of California’s paid family leave act revealed a surprising finding. It tended to decrease the number of children born. Here’s why:

If the Act increased investments in children, then standard economic models posit the number of children should fall, because increases in child “quality” (i.e., investment in children) increases the shadow price of child quantity (Becker and Lewis 1973). Table 5A.2 shows this was the case, with the number of children falling by 2 percent for all mothers (-0.06/2.31, col. 2) and 5 percent for new mothers (-0.10/1.81, col. 4) over the next decade.

What’s the bottom line? With below-replacement birth rates now the norm across the entire developed world—and the norm whenever a nation joins the developed world—we’re on the front end of what could be an immense civilizational change, and it’s not clear that any government, anywhere has an answer to a seemingly irreversible trend.

One more thing …

I’m following the Washington Post scoop that General Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, twice called his Chinese counterpart, Gen. Li Zuocheng, to try to ease Chinese concerns that the United States might strike China.

I’m troubled by multiple aspects of the story, from Trump’s erratic behavior to, quite frankly, Gen. Milley’s actions. There is still much we don’t know, and I’m waiting for more information to provide any meaningful analysis, but the Post’s story does remind me of a different, more dramatic, time in American history—when the United States confronted the Soviet Union while Richard Nixon was drunk and incapacitated.

The incident occurred in the late stages of the Yom Kippur War. The Soviets had threatened to intervene unilaterally after Israel had launched a renewed attack on the Egyptian Army, and there were signs the Soviets were preparing to deploy nuclear weapons to the war zone. Nixon, distracted and drunk, yielded effective control of the government to a small council led by Henry Kissinger:

In the absence of a functioning president, these five men, led by Kissinger, decided to send strong signals to the Soviets to back off. They raised America’s global nuclear alert level to DEFCON III, one step short of imminent nuclear war. They dispatched three warships to the Mediterranean, alerted the 82nd Airborne Division, and recalled 75 B-52 nuclear bombers from Guam. Since that entailed the immediate movement of many thousands of American soldiers, sailors and airmen, Moorer said the decisions would immediately be leaked—not a bad thing, since the Americans wanted to signal to the Soviets how seriously they took the threat.

“At 0400 we went to bed to await the Soviet response,” Moorer’s record ended, save for one last thought: “If the Soviets put in 10,000 troops into Egypt what do we do?”

More:

Through good luck and, perhaps, blind fortune, Moscow and Washington backed away from the specter of a Third World War. Kissinger, to his great credit, began a three-year attempt to try to negotiate peace in the Middle East. To his discredit, when word of the nuclear alert leaked, as it did almost instantly, he deceived the press, saying the president had saved the day, when Nixon had spent the night in a drunken stupor.

The more I read American history, the more I’m convinced that it’s a minor miracle our nation is still here, and we’re all still alive.

One last thing …

Sad news. Norm Macdonald died today. He was one of the funniest men in America, and Twitter is filling with tributes. The bit below includes one of the funniest jokes ever told. Rest In Peace, Mr. Macdonald. You were truly a treasure:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.