Would you like to have The Sweep emailed to you? If you’re new to The Dispatch, sign up here. If you’re already receiving some of our newsletters, update your preferences here.

We made it to August, team! And for my fellow Pandemic Legacy fans out there who listened to my fangirl rant at the end of last week’s Dispatch Podcast, we all know that once you’ve made it through June and July things start looking up a little.

It was another exciting week here of not leaving the house and being at the beck and call of an evermore demanding Brisket who was more formally attired in the picture I’ve linked to than either of his parents have been in months.

And yet the campaign world kept spinning: The president was “just raising a question” about whether to delay our election for the first time in history, rumors swirled about Biden’s VP pick as Rep. Karen Bass potentially moves into front runner status (side note: after being pressed by Steve during our special Friday pod, that’s exactly who Joe Trippi picked ahead of the media reports), and the Trump campaign acknowledged they are undergoing “a review and fine-tuning of the campaign’s strategy” after Bill Stepien replaced Brad Parscale as campaign manager.

Campaign Quick Hits

New Republican voters outnumber Democrats by 4-to-1 in Pennsylvania: The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that “[s]ince the 2016 primary election, Republicans have added about 165,000 net voters, while Democrats added only about 30,000. Democrats still maintain a 800,000-voter edge over Republicans. But that’s down from 936,000 in 2016, when Trump still won the state by less than 1 percent.”

Bad news for the shy Trump voter theory: According to Nate Cohn, “[i]n the last Times/Siena polls of six battleground states, for instance, respondents who voted in the 2016 election said they voted for Mr. Trump over Hillary Clinton by a margin of 2.5 points, which was even more than Mr. Trump’s actual margin of victory. Mr. Trump’s problem wasn’t the number of people who said they voted for him last time: It was that only 86 percent of those who said they voted for him last time said they would do so again.”

Fewer than 1 in 5 approve of Congress: Congressional job approval numbers dropped double digits from their 20-year high in April and May, returning since to their normal, abysmal 18 percent based on the latest Gallup poll.

A quick reminder from Article II of the U.S. Constitution: “The Congress may determine the Time of chusing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.”

You’ve Got Mail

Trump can win re-election even if he’s way behind in the polls. Let me show you how.

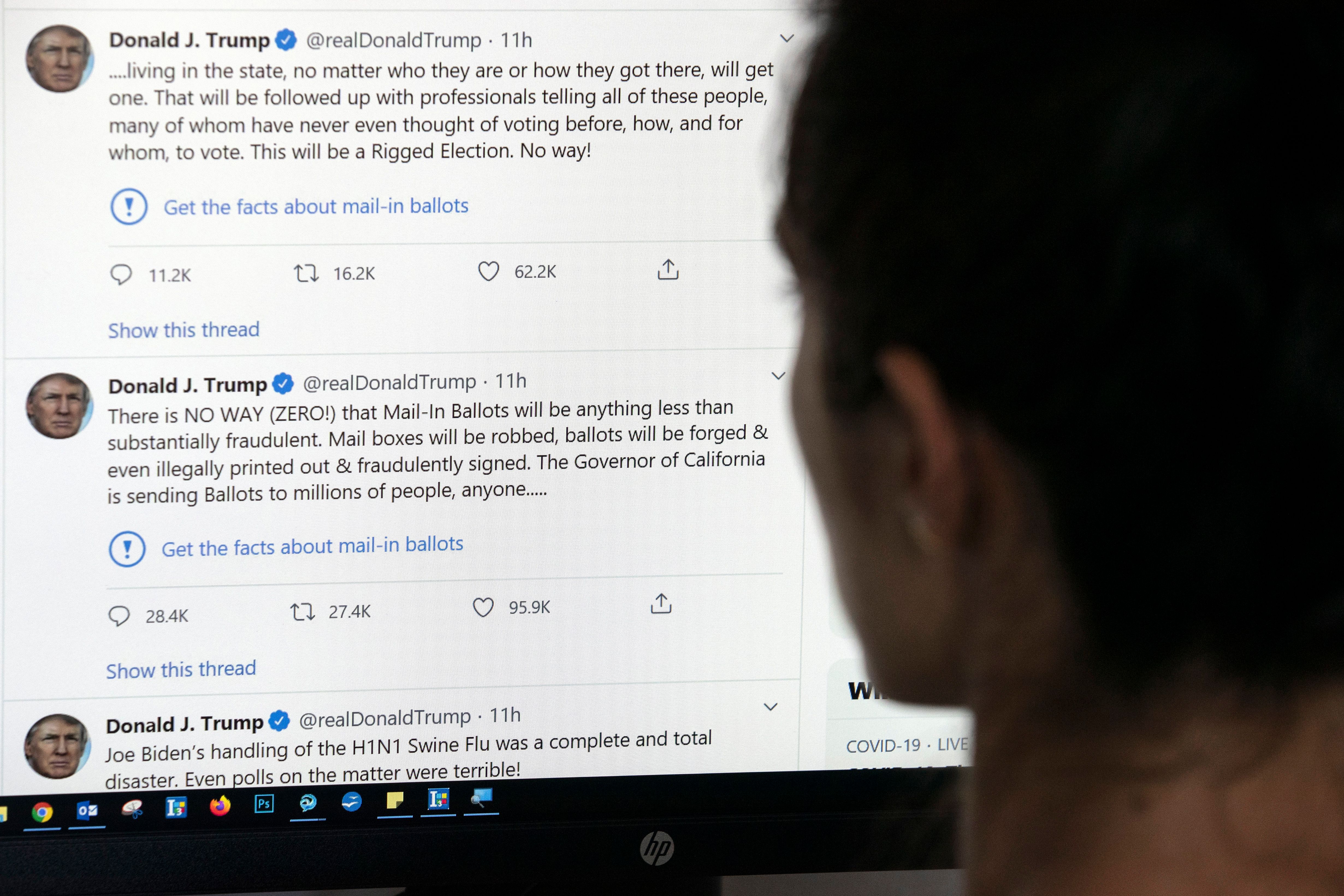

The president has been railing against mail-in ballots for weeks and it has had an effect on his voters. Last week, Harvard CAPS-Harris released their poll which found that 88 percent of Democrats want to have a mail-in ballot option versus only 50 percent of Republicans. Another ABC News/Washington Post poll found that “only 28 percent of Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s supporters saw mail voting as vulnerable to substantial fraud, whereas 78 percent of Mr. Trump’s supporters did.”

So far, every pundit I’ve seen has said this is a bad thing for Trump. But they’re wrong. If anything, the Trump campaign should be trying to drive these numbers further apart.

Why?

Let’s peek at New York’s primary from June 23. Several of the races have yet to be called because of the enormous delay in counting tens of thousands of absentee ballots. By way of comparison, in 2016, 23,000 absentee ballots were returned and validated in New York. This year, there were more than 400,000 absentee ballots returned. Again, everyone I’ve seen is using these numbers to predict that the November election won’t be called for days or weeks. Sure, that may be a problem but they are missing a much, much larger one staring them in the face.

Of those ballots that make it back to their voting precinct, “tens of thousands of mail-in ballots were invalidated for technicalities like a missing signature or a missing postmark on the envelope.” And that’s not even counting the people who requested an absentee ballot that never arrived or arrived after the election.

To make this abundantly clear: Nearly everyone who votes in person has their vote counted but far fewer of those who try to vote absentee have their vote counted. In one study out of Georgia in 2018, the rejection rate for absentee ballots was as high as 17 percent—and that’s of voters who were able to receive their ballots and return them. Currently in New York, they are reporting that 20-25 percent of absentee ballots that were returned have been disqualified.

Normally this doesn’t matter all that much because there isn’t a big partisan difference in absentee voters and both sides have a robust “absentee chase” program in which the campaigns work to ensure their absentee voters get their ballots and fill them in correctly and return them in time to be counted. But that kind of manpower is nearly impossible when absentee ballot requests soar by 20 fold as they did in New York’s June primary.

What does this all mean in terms of November?

Assuming there’s a lot more mail in ballots this time around, Joe Biden may need to be running ahead of Trump by more than 5 points with people who intend to vote to actually receive more valid votes in the final count.*

Currently, Biden is up by 8 points nationally but polls tend to tighten after Labor Day and as Clinton learned in 2016, winning the popular vote doesn’t do you any good. As of now, Biden is only up 6 points in Florida and Pennsylvania. The rest of the top tier battleground states are within 5 points.

Imagine waking up on November 4. Trump is ahead based on in-person votes cast. There’s something like 50 million absentee ballots that have been returned to precincts across the country, which are expected to favor Biden by a wide margin but nobody knows for sure. And now thousands of individual election officials need to determine how many million of those ballots to invalidate because “the signature on the ballot not matching the signature on the state’s records,” “the ballot not having a signature,” a “problem with return envelope,” or “missing the deadline.”

This would be, to put it mildly, a problem on many fronts.

*Showing my math here. In 2016, about 23 percent of all votes were mailed. Given the pandemic, I’m assuming this number jumps to 40 percent. Looking at current polling, I’m also assuming that Biden voters will be three times as likely as Trump voters to vote by mail. Finally, assuming a 10 percent loss rate (failure of mailed ballots to arrive or make it back in time) and a 17 percent rejection rate, I’m rounding off to a 25 percent overall mailed ballot failure rate (although based on the current numbers in New York, 25 percent would be on the lowest end).

This means that out of 100 voters, Joe Biden would be starting with 50 and Donald Trump with 45 (and five more voters are voting third party roughly tracking 2016’s popular vote outcome, but we are going to ignore them to make the math a little easier). Thirty of Biden’s voters would request a mailed ballot but only 23 of those would be returned and accepted. He’d lose 14 percent of his voters to ballot failure in this scenario. On the flip side, only nine of Trump’s voters would request a mailed ballot and 7 would be counted. In that scenario, despite a 5-point lead, Biden ends up with 43 votes … same as Trump.

Bringing Down the House and Senate

Andrew Egger, who many of you know as one of your Morning Dispatchers and from his great campaign reporting, pitched in this week with a top line look at the Senate map. To paraphrase one of my favorite Saturday Night Live skits of all time: Who are they? Why are we here? Take it away, Andrew...

To understand the scope of the 2020 Senate electoral picture, it’s helpful to take a look back at what happened in 2018.

Two years ago, the Democratic Party fared extremely well in the midterm elections. The 40 seats they picked up in the House, while a more modest haul than the 63 seats that changed hands in the red wave of 2010, were still good for the third-biggest swing in the last 40 years. Democrats also picked up seven governorships and hundreds of state legislative seats. A good year pretty much across the board for Team Blue, is the point.

But it didn’t seem that way in the Senate: Mitch McConnell’s caucus actually strengthened its position in the midterms, picking up two net wins to move themselves from 51 seats to a much more breathable 53.

The primary reason for this was that Senate Democrats came into 2018 facing a legendarily bad electoral map. Recall that a third of the Senate comes up for re-election every two years; in 2018, 26 of the 35 seats being contested—a whopping 74 percent—were held by Democrats. Worse yet, 10 of those incumbents were trying to hold onto states Donald Trump had won just two years prior.

Given this lay of the land, losing only two seats was arguably still a strong Democratic showing: Capturing two out of the nine seats the GOP was defending gave the Democrats a .222 batting average compared to the .153 posted by Republicans (four pickups out of 26 opportunities). But the point is that, when it comes to predicting Senate election results, no factor—not even a historic wave of voter sentiment—matters more than the map you started out with. It establishes both your ceiling and your floor.

In 2020, the script is flipped. Only 12 Democrats, compared with 23 Republicans, are defending seats this year. Of those 12 seats, 10 are considered by most election experts to be shoo-in re-elections, with Sen. Gary Peters of Michigan a slight favorite in his race and Sen. Doug Jones of Alabama the only real underdog among them. (It is, after all, Alabama, and Jones doesn’t have the ace-in-the-hole of running against an accused child molester this time around.)

Things look more rickety on the other side of the aisle. The Cook Political Report rates 10 of the 23 currently Republican seats to be virtual locks, four more likely to be safe, and two—Sen. Kelly Loeffler’s seat in Georgia, and that of Sen. Pat Roberts (who is retiring) in Kansas—favoring the GOP in a close race.

That leaves seven seats: Sen. Cory Gardner of Colorado, Sen. David Perdue of Georgia, Sen. Joni Ernst of Iowa, Sen. Susan Collins of Maine, Sen. Steve Daines of Montana, Sen. Thom Tillis of North Carolina, and Sen. Martha McSally of Arizona.

Like Jones among the Democrats, McSally is the only real underdog here—after all, she was already the recipient of one of those two GOP losses back in 2018 at the hands of Democrat Kyrsten Sinema, only making it into the Senate at all as an appointment to fill the seat of the late John McCain.

The other six are still anybody’s game, and we’ll dig into those races in this space in the weeks ahead. For now, the important point is simply that the vast majority of toss-up races this time around are in seats currently held by Republicans. Even if everything goes right for the GOP for the rest of the year, it’s highly unlikely they’ll push past their current 53 seats. Instead, it’s their turn to play defense and hope they can hold off the Democrats enough to maintain their majority for another two years.

The Scorepian King

Assume for a moment that the Trump campaign is right, and there are, as Jonah put it, a substantial number of SMAGAs (Secret Make America Great Again voters) who aren’t showing up in the polls. How would the campaign know? What would they do about it?

They would turn to their data and digital teams.*

Think of it like Moneyball for political campaigns. (I know, I know, everything these days is “moneyball” for something but this really is!) Gone are the All the King’s Men days in which the grizzled campaign veterans listened to their gut to determine the campaign’s strategy. Big data and Facebook have changed all of that.

If polling is descriptive, this stuff is prescriptive.

At its most basic, voter scores are on a quadrant and usually out of 100 points. On the one axis, there’s who the person is likely going to vote for and on the other is how likely they are to vote at all. As a voter, you may score a 98 on the Trump axis, but if you haven’t voted since Jimmy Carter was running for re-election, you’d have under a 20 on your voting propensity score.

That all makes sense but how does a campaign create these scores and what do they use them for?

They start with voter files. This will have your name, where you live, whether you are registered with a party (depending on the state), and how often you have voted. They’ll add in your donor history. They can buy consumer data like whether you own a gun and even some health care information. From there, the campaign will run large, rolling micro surveys. A poll that you see reported in the media may rely on fewer than a thousand voters, but these surveys can be around 2,500 people. A campaign uses the answers from that survey to score the other voters in their voter file that most closely resemble the survey respondents. And then the campaign may compare those scores with their own behavioral observations. For example, they will check to see that a voter who has signed up on the campaign’s website has a high score based on the algorithm created by the survey thereby validating the algorithm.

Now things get fun.

Based on those voter scores, a campaign can send 100 names of voters they want to target to a company like Facebook … along with a wad of cash. Facebook will match those names with profiles and compare thousands of data points for those 100 people to figure out what they have most in common. Then Facebook will go find a million other people that look the most like the 100 names the campaign gave them. Facebook doesn’t share the data, what data they found predictive, or the names of the million people. But in just a few clicks, the campaign can target those million people with an ad based on what they think they know about the 100 people in their voter file.

This applies to turnout operations as well. Based on social science, we know that peer-to-peer communication is the most effective campaign tactic. A campaign can ask its data team to find 10,000 voters in Macomb County, Michigan, who have above a 60 on Trump but only between a 35-45 on voting propensity. Those 10,000 addresses are then sent to the Republican Party’s headquarters in Detroit, which mobilizes a few hundred volunteers to go knock on their neighbors’ doors in a single weekend to tell them where their voting precinct is and how to early vote.

Week by week, those large, rolling surveys continue and scores will get refined. A campaign may want to add “affiliation scores” based on issues. They can ask the data team to create an algorithm to spit out a list of voters who are below 40 on the Trump axis but are over 80 on a “soco” (social conservative) score to target with ads about religious liberty.

There’s one other issue that’s worth discussing. When Pepsi wants to increase its market share, they target Coke drinkers to persuade them that Pepsi is better and they may target non-soda drinkers to introduce them to their product. But as far as I know, Pepsi never targets Coke drinkers to convince them to stop drinking soda altogether.

But if a campaign is looking at a voter’s score and realizes that the person is never going to vote for their candidate but also is a marginal voter at best, they have every incentive to get that person to stay home. Voting takes effort and a successful voter depression strategy can obviously make a big difference in a tight race ... in theory.

But is it happening in 2020? To quote our friends in the midwestern battleground states: Oh yeah, you betcha!

It’s rarely attempted by the campaigns themselves, but you can bet that Biden’s allies are looking hard at 2016 Trump voters who are never going to vote for Biden but are getting tired of the president’s shenanigans and vice versa. Imagine a Facebook ad targeted at weak Trump voters who are low propensity voters: “Politicians are all the same. Donald Trump promised he’d build the wall. He didn’t. Joe Biden can’t string a sentence together. He’ll be at the mercy of AOC. Send them all a message: Stay home.” Ok, it won’t be that blunt. But it’ll be close.

As Fraulein Maria taught us in the Sound of Music, now that we know the data to sing, we can sing most anything!

Which is all to say, now that we’re all on the same page with campaign data operations we can have more sophisticated and fun conversations in this newsletter as campaigns shift to their turnout operations and absentee chase programs in the weeks to come.

*Which is exactly what I did in writing this piece. Tyler Brown, former RNC dgital director and president of Hadron Strategies, and Ron Steslow, former Carly for President data guru and President of Tusk Inc. were enormously helpful as I thought about how to explain this world to you.

Photograph by AFP/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.