An unpopular Democratic president declares his Republican rival to be a threat to American democracy. Like Hitler in Germany or Mussolini in Italy, his Republican opponent is a “front man” for fascism and the “crackpot forces of the extreme right wing.”

“I know that it is hard for Americans to admit this danger,” the president declared. “American democracy has very deep roots. But, if the antidemocratic forces in this country continue to work unchecked, this nation could awaken a few years from now to find that the Bill of Rights had become a scrap of paper.”

The Republicans were emulating the “the tragic story of what happened in Germany,” the president insisted. “We know how Hitler used antisemitic propaganda as a way of stupefying the German people with false ideas while he reached out for power.” The coming election “is not just a battle between two parties. It is a fight for the very soul of the American government.”

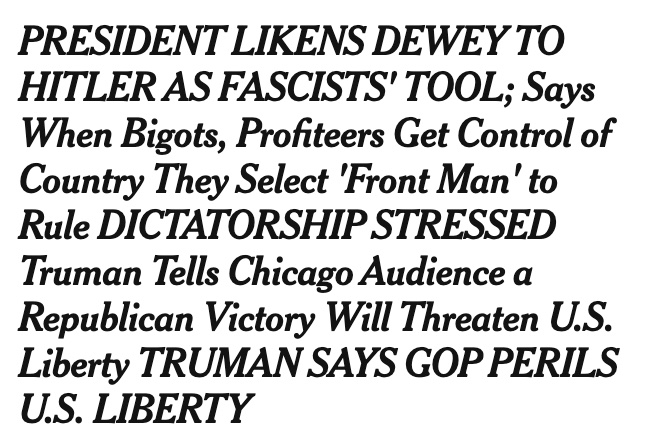

This was Harry Truman, at a packed Chicago stadium, making his closing argument in the 1948 presidential election. The address, broadcast nationwide on the radio, received considerable coverage. The New York Times put its story about it on the front page:

Now, the idea that Thomas Dewey was a fascist is just contemptible, vile slander. As district attorney in New York, he tried and convicted Fritz Julius Kuhn, the head of the German-American Bund, which directed fundraising for the Nazi cause in America. Harold Stassen, Dewey’s chief opponent in the primaries, made outlawing the Communist Party his signature issue. Dewey forthrightly opposed the idea, at some political risk. Dewey proclaimed in a debate:

I am unalterably, wholeheartedly, and unswervingly against any scheme to write laws outlawing people because of their religious, political, social, or economic ideas. I am against it because it is a violation of the Constitution of the United States and of the Bill of Rights, and clearly so. I am against it because it is immoral and nothing but totalitarianism itself. I am against it because I know from a great many years experience in the enforcement of the law that the proposal wouldn’t work, and instead it would rapidly advance the cause of Communism. … Stripped to its naked essentials, this is nothing but the method of Hitler and Stalin. It is thought control, borrowed from the Japanese war leadership. It is an attempt to beat down ideas with a club. It is a surrender of everything we believe in.

That doesn’t sound very fascist, does it?

Dewey was one of the most successful New York governors in history, winning three consecutive elections. He was not a right-wing firebrand; some called him a “pay-as-you-go liberal” insofar as he was a fiscal conservative who thought government services should be generous, but not beyond. He rounded up no Jews and never hinted he wanted to invade Poland. The hard right of the Republican Party disliked Dewey, partly for being a liberal Republican, partly because Dewey was the chief architect of sidelining Robert Taft’s bid for the GOP nomination in 1952 in favor of Dwight Eisenhower (who went on to crush Adlai Stevenson in the general election). Reading the New York Times’ obituary for Dewey, you would have no idea that the president of the United States had once called him the frontman of a domestic Nazi putsch to end American democracy.

What’s the point of this largely forgotten snippet of political history? Well, for starters, it’s simply to point out that Joe Biden’s decision to go “full Hitler” against Donald Trump is not as unprecedented as many—on both the right and left—seem to think.

Argumentum ad Hitlerum was used against Barry Goldwater, too. On the eve of the 1964 convention, CBS Evening News correspondent Daniel Schorr reported from Germany that Goldwater’s rumored German vacation was a Nazi plot of some kind. “It looks as though Sen. Goldwater, if nominated, will be starting his campaign here in Bavaria, center of Germany’s right wing,” Schorr told Walter Cronkite, adding that the location was “Hitler’s onetime stomping ground.” Schorr went on to claim that an interview with Der Spiegel should be seen as an attempt by Goldwater to “appeal to right-wing elements.”

“Thus,” Schorr declared, “there are signs that the American and German right wings are joining up.” The only problem? None of it was, you know, true. The Der Spiegel “interview” was simply a reprint of an old interview elsewhere. Goldwater never planned to go to Germany (and didn’t end up going to Europe at all).

Goldwater called it “the damnedest lie I ever heard” and told Victor Lasky (my late brother’s godfather) that it “made me sick to my stomach. My Jewish forebears were probably turning over in their graves.”

California Gov. Pat Brown declared that Goldwater’s acceptance speech had the “stench of fascism,” and all that was missing was “Heil Hitler.” Syndicated columnist Drew Pearson wrote that “the smell of fascism has been in the air at this convention.” And in the general election, LBJ constantly tried to link Goldwater with the omnipresent climate of “hate.”

Readers of Liberal Fascism know that I could go on with Reagan, the Bushes, Gingrich, etc. Heck, FDR in his 1944 State of the Union Address, proclaimed, “Indeed, if such reaction should develop—if history were to repeat itself and we were to return to the so-called ‘normalcy’ of the 1920’s—then it is certain that even though we shall have conquered our enemies on the battlefields abroad, we shall have yielded to the spirit of Fascism here at home.”

Now, if Donald Trump were anything like a conventional conservative Republican, I’d probably be leading the barricades to write “there they go again” columns. But I can’t do that with regard to Trump.

I’m not arguing that Trump is “literally Hitler” or even figuratively Hitler. But, for the umpteenth time, one can fall well short of being Hitler and still be pretty bad. There’s a weird tendency in public debates to take terms for the worst thing—Hitler, genocide, totalitarianism, Communism, murder—and drain them of their (im)moral status. I’ve had conversations with nice liberals who know I cannot stand Trump yet nonetheless recoil when I say he’s “not Hitler” as if I am defending him.

This is not a left-wing thing, it’s a human thing. There are plenty of right-wingers who would have the same reaction if I were to say, “Bernie Sanders is not a Stalinist.”

I think Donald Trump is, in fact, a legitimate threat to democracy and the rule of law. Indeed, I think one of the primary reasons he’s running for president again is to avoid being held accountable for his past assaults on democracy and the rule of law.

Just yesterday, his lawyers were in court arguing that a sitting president could order Seal Team 6 to assassinate a political rival and be immune from criminal prosecution—so long as he wasn’t impeached. The day before, his lawyers argued in Georgia that because Trump hadn’t received “fair warning” that trying to steal the election was illegal, he can’t be prosecuted for it. He has made arguments about “terminating” the Constitution for the sole purpose of putting him back in the White House. He vows that his presidency will be about “retribution,” and constantly threatens the Biden administration with criminal prosecution if it continues the legal proceedings against Trump. He insists that all men who assaulted the police and smashed into the Capitol are “hostages” of the Biden administration.

All of these things fall well-shy of making Trump a Hitler. They are more than bad enough, but we can have that argument another day.

Instead, I just want to make one of the simplest, most basic, points in politics and life.

Don’t cry wolf.

If you don’t understand why so many conservatives—and not just MAGA types—have so much deep-seated distrust of the media, academia, and other elite institutions, it’s because you trust the media, academia, and other elite institutions too much. Jonathan Haidt has found that conservatives generally do better at so-called ideological Turing tests. Generally speaking, conservatives can more accurately describe liberal arguments than liberals can describe conservative ones. This makes sense when you realize that conservatives constitute a minority subculture at most elite institutions. We hear the left’s best arguments all the time, while liberals often just hear the caricatures of conservative arguments made by other “authoritative” progressives.

This is why accusations of cryptofascism or right-wing insanity often take flight so easily. If you don’t actually know the conservative argument on an issue and only know the invidious descriptions offered on MSNBC or in Paul Krugman columns or by your college professors, it doesn’t shock you when you’re told that conservatives hold positions no reasonable person would hold. You’ve been taught that being a conservative is unreasonable (and sinister).

The successful rise of conservative media cannot be understood without knowing that, for generations, the dominant narratives about conservatives were unfair to conservatives. The tragedy, of course, is that a lot of the right is now playing catch-up, making many of the same mistakes the stewards of mainstream media and other institutions made. Depending on the outlet, there’s as much catastrophizing on the right these days as there ever was on the left. Donald Trump takes advantage of this constantly, knowing that his rhetoric about vermin, witch hunts, fascists and Marxists, etc. will play well in his loyal echo chambers.

(One of the things about The Dispatch I’m most proud of is that many of our readers are skeptical of the dominant narratives of the left and right. In surveys, one of the primary reasons left-of-center Dispatch subscribers say they read us is that they want to know what the good faith, serious, nonpartisan conservative arguments are for this or that. Many of our conservative readers have a similar desire to separate principled arguments from the hype and hysteria of partisan media.)

Again, I think many of the warnings about the threat posed by Trump made in good faith from people of the left have substantial merit, even if I think the “he’s literally Hitler” rhetoric is overblown. But American politics didn’t begin in 2015, and even if these sincere progressives don’t know the history of anti-conservative demonization, that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. I can’t tell you how many conversations I’ve had with decent conservatives since 2015 who’ve responded to criticisms of Trump by saying, “That’s what they said about Reagan.” It’s really hard to say to them—persuasively—“Yeah, but it wasn’t true about Reagan. It is true about Trump.”

It’s not just that after generations of crying wolf, the left has lost credibility with the right. It’s that after generations of left-wing wolf crying, the right has built institutions and arguments dedicated to the proposition that right-wing wolves don’t even exist. This ideological infrastructure of the left and right wasn’t built yesterday, and it can’t be dismantled overnight. It will take time, and a recognition from people of goodwill across the ideological spectrum, that there’s plenty of blame for this mess to go around.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.