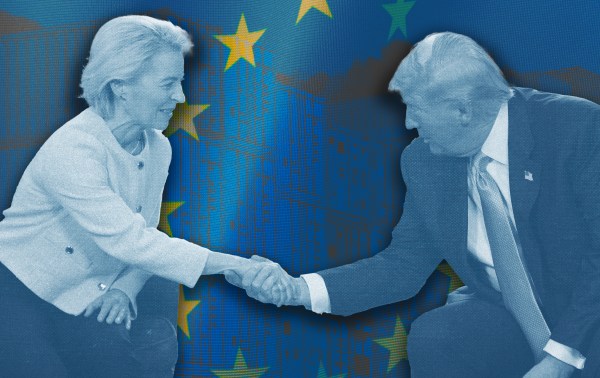

The trade deals keep coming in, and the president is thrilled. “It’s certainly the biggest trade deal ever made,” boasted Donald Trump about his administration’s framework agreement with the European Union to set a 15 percent rate on all imports between two of the world’s largest economic powerhouses. That’s up from the roughly 1 percent average tariff rate in place before Liberation Day but down from the 30 percent Trump threatened the EU with earlier this year.

Like many of the deals Trump has made ahead of today’s drop-dead date on reimplementing tariffs on imports, the devil is in the details. There are reasons to be skeptical the EU will follow its pledge to purchase hundreds of billions of dollars in American energy and invest hundreds of billions of dollars of capital in the United States. But the promise was good enough for Trump.

“I mean, it’s a massive deal for everybody,” he said.

Well, not everybody. American wine distributors, retailers, and producers aren’t exactly popping their champagne (or California sparkling, as it were). That’s because this deal amounts to massive disruption in their relatively small but growing industry, both when it comes to importing European wine and exporting American wine. Even with Trump’s temporary pause on so-called reciprocal tariffs, American small businesses in the industry have already felt the pinch of trade protectionism.

“My business made, on paper, about $350,000 last year,” says Harry Root, the co-founder of Grassroots Wine, a distributor in South Carolina and Alabama. “We’ve already paid more than $175,000 in tariffs this year.”

Domestic wine distributors, retailers, and producers have no appetite for the federal government to protect their interests through trade action, says Ben Aneff, the president of the U.S. Wine Trade Alliance and the managing partner at Tribeca Wine Merchants in Manhattan. They want a “zero to zero” regime, with no trade barriers, so that European and American wines flow freely (in bottles, of course) across the Atlantic. Instead, Aneff and this alliance of wineries, distributors, and retailers are fearing the possibility that the American wine industry could face some difficult contractions.

From the perspective of a protectionist ideologue, the concept is hard to grasp. If European wines will be more expensive to buy in the United States, is it not the case that more Americans will buy more American wine, and boost our own domestic industry? But as is true for any number of industries, the wine business is just not that simple.

Some complexities in the American wine industry are straightforward. As with anything related to agricultural production and hospitality, profit margins are small and precarious when externalities like trade actions come to bear. Wines from the U.S. and Europe aren’t perfect substitutes for each other, with distinguishing factors like region, grape varietal, and vintage—not to mention the reputation of European wines—making a huge difference with consumers. Winemaking, from planting the grapes to bottling the good stuff, requires years of investment and planning before you bring a new product to market, so it’d be impossible for the domestic industry to match the American demand for European wines overnight even if winemakers could magically re-create the terroir of a perfect French Burgundy.

Meanwhile, producers say their domestic customers need to be familiar with the OG wines from Europe if wines from the States have a chance to compete.

“We produce world-class wines of European varieties: pinot noir, chardonnay, pinot gris, a bunch of Alsatian wine, we make grüner veltliner, and riesling,” says Mike Osborn, the CEO of Willamette Valley Vineyards in Oregon. “If a consumer doesn’t know what the standard is for those, if they haven’t tried rieslings from Germany, if they haven’t tried pinot noir from Burgundy … if customers don’t know that, they lose.”

The idiosyncrasies of the legal distribution of wine, foreign and domestic, in the United States complicate things further. Thanks to the three-tier system of alcohol producers selling to distributors who sell to retailers (a vestige of the post-Prohibition era), wine producers are severely limited in how much they can sell directly. Enter wine distributors, who buy from domestic winemakers and importers alike, then sell to retailers and restaurants. These distributors aren’t just legally required middlemen but the industry’s knowledgeable and connected sales team who by necessity have a finger on the pulse of the American wine drinker’s preferences. Producers and retailers depend on their relationships with distributors, who rely on selling European wines at higher margins to stay whole.

Domestic producers, meanwhile, are eager to boost their own overseas business, which already faces stiff competition not only from European winemakers but those in other highly regarded regions like South America, Oceania, and South Africa. But this EU trade agreement works both ways, meaning American wines will also be more expensive in the most sophisticated wine market: Europe.

“We really need people to love U.S. wines,” Aneff says. “Long-term tariffs on European wines would continue to degrade the demand for U.S. wines overseas.”

Wine is just one of scores of industries directly affected by higher tariffs, and it’s hardly the biggest or most politically connected. I asked Aneff to assess his group’s lobbying effort to convince the administration of the compelling case he and the other industry leaders I spoke with have made. Meetings on Capitol Hill, letters and communications with the U.S. trade representative, and briefings for the media—he says his organization and several others that advocate for the wine industry have done all they can to tell the stories. It’s up to policymakers in government to listen, and so far they haven’t.

All of this underscores the error of Trump’s protectionist worldview. The unique characteristics, regulatory and legal regime, and established practices of the wine industry are difficult to understand for those on the outside. There’s no way that trade negotiators, Commerce Department bureaucrats, or even our brilliant deal-making president can know enough about how wine is made, distributed, and sold to set a “correct” tariff amount. And that goes for every sector of the American economy, all of which have their own complexities that trade intervention can distort in ways predictable and unpredictable. No one tariff structure could possibly cure the supposed problems created by America’s trade deficits.

Amid all of the economic and political debate over trade protection, however, those who make their livelihood in the wine industry are simply asking for the government to let them pursue their passion in peace.

As Kelby James Russell, the co-founder of Apollo’s Praise winery in the Finger Lakes of New York state, put it, “I think when we’re talking about these tariffs, it feels like not just an existential threat to the current wine industry, but also to wine itself: this idea that it’s commodified and can be tariffed and used as a cudgel, instead of being something that keeps that romance and keeps the story alive and brings more people together in a time when people are having a hard time coming together.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.