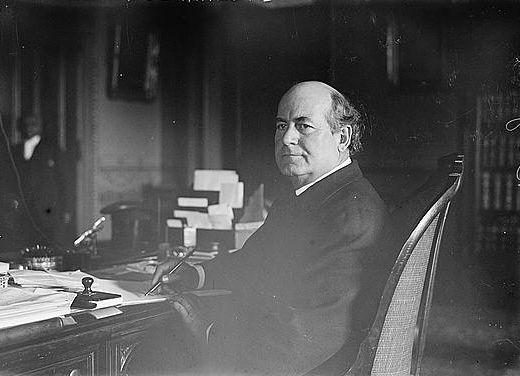

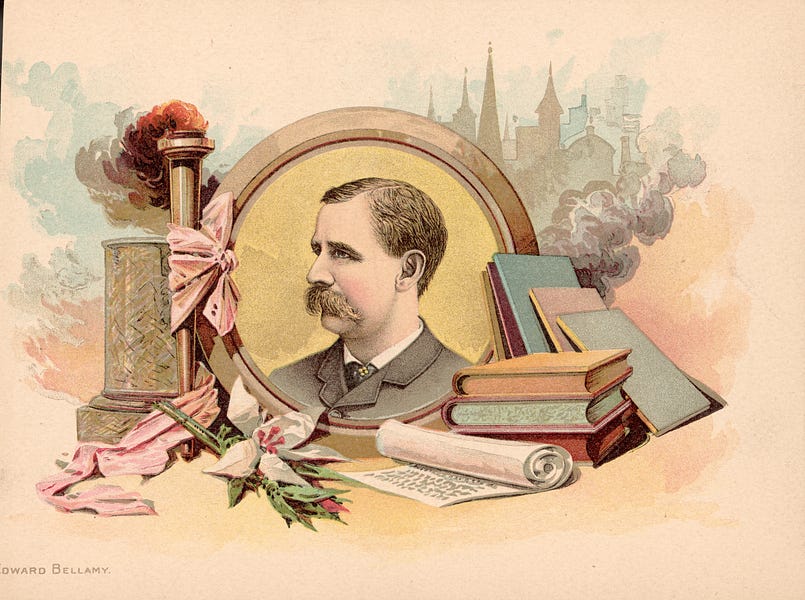

American elites are very excited about nationalism. Scholarly journals, op-ed pages, and a slew of books on the topic have been pouring forth in a torrent. Emphasizing different angles and arguments—international relations, economics, history, politics, and of course, President Trump—these efforts vary in seriousness and quality. A few see nationalism as a grave threat to the American experiment; many others see it as its salvation. But there is one interesting commonality: Despite the dedication to the topic of nationalism—specifically American nationalism—none of them (see footnote) mention Edward Bellamy or his utopian science fiction book, Looking Backward.

This may not seem like a shocking oversight. Except that Looking Backward, first published in 1888, is the most influential novel you’ve probably never heard of—or read. Not only did it create an American genre of utopian fiction and inspire a generation of writers and intellectuals, it also launched an intellectual and political movement called “nationalism.”

Bellamy’s prophecy.

Looking Backward was the third best-selling book of the 19th century, after Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. In his foreword to the 1960 edition, the philosopher Erich Fromm called it “one of the most remarkable books ever published in America.” In 1935, the historian Charles Beard, the philosopher John Dewey, and Edward Weeks, the longtime editor of The Atlantic, each independently listed it as the second-most influential book published since 1885, surpassed only by Marx’s Das Kapital (which as a writer for The New England Quarterly noted in 1944, means they believed it was the most influential American book published in that period). Dewey wrote in 1934, “What Uncle Tom’s Cabin was to the anti-slavery movement, Bellamy’s book may well be to the shaping of popular opinion for a new social order.”

Indeed The American Fabian wrote of Bellamy in 1898, the year of his death:

It is doubtful if any man, in his own lifetime, ever exerted so great an influence upon the social beliefs of his fellow-beings as did Edward Bellamy. Marx, at the time of his death, had won but slight recognition from the mass; and though his influence in the progressive struggle has become paramount, it is through his interpreters, and not in his own voice, that he speaks to the multitude. But Bellamy spoke simply and directly; his imagination conceived, and his art pictured, the framework of the future in such clear and bold outlines that the commonest mind could understand and appreciate.

The plot of Looking Backward seems a bit pedestrian for science fiction. The protagonist, Julian West, is a Rip Van Winkle character who falls into a deep hypnotic sleep at the end of the 19th century and awakens in the year 2000. When he wakes, he encounters a good-natured fellow, Doctor Leete, who serves as his guide through the socialist utopia that awaited America. Capitalism has been interred and replaced with a new cooperative system in which all Americans are conscripted into industrial armies. For-profit business has been done away with as all forms of production have been nationalized and subsumed into the Great Trust. “When the nation became the sole employer,” explains Dr. Leete, “all the citizens, by virtue of their citizenship, became employees, to be distributed according to the needs of industry.”

At 21, every student joins an industrial army for three years of training as a common laborer. When that’s over, if his grades and job performance are adequate, he chooses a profession or trade. Whichever path he picks, the pay will be the same. Women are treated similarly, but their industrial army focuses on vocations best suited for the fairer sex. When women marry, they keep working. But when they get pregnant they have generous maternity leave to raise the next generation of laborers. Everybody retires from active service at 45, when the good life really begins.

Bellamy had a gift for predicting technological developments—he foresaw airplanes, submarines, radios, and television. But his most interesting prediction was the introduction of “credit cards” (his term), which he thought would eliminate all of the evils associated with money. “A credit corresponding to his share of the annual product of the nation is given to every citizen on the public books at the beginning of each year, and a credit card issued him with which he procures at the public storehouses, found in every community, whatever he desires whenever he desires it,” Leete explains to West. “This arrangement, you will see, totally obviates the necessity for business transactions of any sort between individuals and consumers.”

Of course, in the real world, credit cards fell a bit short of this utopian ideal.

The overriding idea of Looking Backward—and Bellamy’s subsequent writings—was that cooperation and social solidarity should replace the dog-eat-dog individualism of capitalism. For Bellamy the umbrella is an acute symbol of such atomism. “The private umbrella is father’s favorite figure to illustrate the old way when everybody lived for himself and his family,” Leete’s daughter, Edith, explains. “There is a nineteenth century painting at the Art Gallery representing a crowd of people in the rain, each one holding his umbrella over himself and his wife, and giving his neighbors the drippings, which he claims must have been meant by the artist as a satire on his times.”

In the year 2000, whenever it rains, giant awnings extend over the streets keeping everyone, rich and poor alike—if there were still rich and poor—equally dry.

The birth of a movement

Whether this sounds like a quaintly naïve yarn or a somewhat sinister vision of totalitarianism, that’s not how many received it. While initial sales were unimpressive, Looking Backward caught on in Boston and was rereleased under a new publisher—Houghton Mifflin—at which point it began to take off. By the time Bellamy’s follow-up book, Equality, hit the stands in 1897, Looking Backward had sold more than 400,000 copies (some estimates put the number over 1 million); a staggering figure at a time when the U.S. population was about a fifth of what it is now.

Looking Backward inspired a mass “Nationalist” movement, dedicated to “the nationalization of industry and the promotion of the brotherhood of humanity.” The first Nationalist Club appeared in Boston in the summer 1888, founded by a labor reporter for the Boston Globe. The following year it started publishing The Nationalist, a monthly paper. It wasn’t long before clubs sprouted up across the country. Two years after the publication, there were clubs in 27 states and the District of Columbia. In Chicago, the Collectivist League, founded in April 1888, changed its name to the Nationalist Club of Illinois 10 months later. Soon there were hundreds of such clubs. One estimate held that there were some 4,000 “Bellamy societies” in the United States and hundreds more in Holland, Denmark, and Sweden.

The Nationalist was soon replaced with a weekly newspaper, New Nation, edited by Bellamy himself and “pledged to all the Nationalistic principles that will be realized in the New Nation.” Its aim was to translate the passion of the Nationalist movement into a full political program (a sister publication, Nationalization News, appeared in the U.K.). Bellamyite Nationalists launched slates of candidates in such places as California and Rhode Island.

As the Nationalists became a full-blown grassroots movement, Bellamy built his coalition by finding common cause with the Farmer’s Alliance and other agrarian and labor movements around the country. Bellamy endorsed the Populist ticket in Massachusetts and often spoke at Populist events around the nation. “Nationalist” and “Bellamyite” soon became terms of praise or approbation depending on one’s politics. When the Texas legislature passed a bill authorizing the state to pay for school textbooks, it was greeted by the Nationalists as a big win for the cause. John Hope Franklin recounts how the New York Sun denounced the governor-elect of Texas as a “blatant Bellamyite, a nationalist, and a corporation hater.” Bellamy replied in The New Nation: “To be denounced in such terms by the Sun, which is the most consistent thick and thin champion of the plutocratic movement to be found in this country, is the best possible certificate of character for a reformer.”

But it was the launch of the People’s Party—also known as the Populist Party or simply the Populists—that both diluted and expanded Bellamy’s influence. Bellamy welcomed populism as a kindred effort, if not a wholly Nationalist one. He hopefully saw it as a major step forward in the quest toward Nationalism. There was considerable overlap between the two movements, both philosophically and in terms of membership. Many populists were Bellamyites and many Bellamyites were populists. A Nationalist from Michigan attending the St. Louis meeting of the Populist Party observed that “The disciples of Bellamy were present in large numbers … The People’s party is educating the people in Nationalism just as fast as they are ready to receive it.”

William Dean Howells of The Atlantic, the “Dean of American Letters,” said that Bellamy “virtually founded the Populist Party.” One wag dubbed the Populist Party platform of 1892, “a curious mingling of Jeremiah and Bellamy.” The 1892 platform called for sweeping nationalization of banks (via postal savings accounts), the telegraph, telephones, and the railroads (“We believe that the time has come when the railroad corporations will either own the people or the people must own the railroads.”)

As Bellamy’s philosophy had greater public exposure when allied with the People’s Party, the Nationalist cause was eventually subsumed into the People’s cause, as it were. Despite some modest success—in 1892, it was the first third party to win electoral votes since the Civil War—the People’s Party evaporated as most third parties do. In 1896, they joined forces with the Democrats. William Jennings Bryan accepted the nomination of both parties as a “fusion” candidate. Bryan lost that election to William McKinley.

Many of the diehard populists, robbed of a home, scattered into other movements. A large faction joined the Socialist Party of America under the leadership of Eugene Debs.

Bellamy’s New Deal.

The story of Bellamy’s influence does not end there, though. A generation later Bellamy’s Looking Backward and the movement it sparked were rediscovered as part of an intellectual and political project to find a usable past for the new, or renewed, nationalism. After the onset of the Great Depression, Bellamy Clubs began sprouting up like mushrooms after a heavy rain. An International Bellamy League was created, with chapters across Europe and South Africa. Looking Backward was published in more than 20 languages, including Esperanto. In 1934, a meeting of the California chapter filled the Hollywood Bowl. On May 4, 1934, the Christian Science Monitor ran a long article: “Bellamy Went to Year 2000 for New Deal, Part of Which Is Being Put into Use Today.” It went on to compare Bellamy to FDR.

On February 3, 1935, the New York Times ran an Associated Press story headlined, “Bellamy’s Widow, 70, Hails the New Deal; Holds it Partly Fulfills Husband’s Prophecy.” “As I listen to President Roosevelt and other leaders declaring that we must build a new order of society in which there is sufficiency for all, I feel that the world is at last beginning to catch up with Edward Bellamy.” The story went on to explain how both she and her two children were active in the “Bellamy Club movement” (her son was the editor of the Cleveland Plain Dealer). The article also noted that the Tennessee Valley Authority was foreseen in the pages of Looking Backward and that Mrs. Bellamy was particularly pleased that the director of the TVA was the author of a forthcoming biography of Bellamy.

The previous September, Ida Tarbell, the famed muckraking journalist who took on Standard Oil, penned an essay, “The New Dealers of the Seventies: Henry George and Edward Bellamy.” Tarbell plausibly argued that the formative experience for both Henry George—the idiosyncratic and hugely influential economist—and Bellamy was the “Long Depression” of the 1870s. Death, Tarbell wrote of Bellamy, “did not end his work. From the day they were published until now, Looking Backward and Equality have sold steadily. Today, as in 1898 [the year Bellamy died], groups bearing Bellamy’s name gather regularly in this and other lands to study his plan for the perfect industrial state. … Bellamy’s new nation is woven into the thinking of these people. If out of the depression of the 1930s there is to come a veritable New Deal, it will in no small measure” be Bellamy’s effort to convince the people “that a happier world waits our making.”

***

What to make of this curiously forgotten chapter in American Nationalism? A few thoughts come to mind.

First, for all the talk about how nationalism is the new organizing principle here and abroad, it is interesting how few of its champions seem to understand or acknowledge that nationalism as a cure for what ails us is hardly a new idea here or abroad (my friend and former National Review colleague Rich Lowry is one of a few notable exceptions). For instance, the phrase “wave of the future” entered the popular lexicon 80 years ago when Anne Morrow Lindbergh published a booklet with that phrase as the title. The wave of the future she had in mind was the collectivism and nationalism spreading across Europe.

In America, nationalism, in one form or another, is always someone’s idea of a new idea.

Second, it is remarkable how tinny and paltry this new nationalism is compared to the movement Bellamy inspired, never mind the “New Nationalism” of Teddy Roosevelt or FDR’s New Deal. Where are the new nationalist clubs in America? A couple conferences among the same couple dozen writers and cable TV hosts seems meager by comparison. Where is the burgeoning “nationalist” party in the offing? If your answer is they don’t need one because that party is Trump’s GOP, then you’re conceding how far short of the mark the latest new nationalism has fallen. Most Republican elected officials are desperately waiting for the Trump regency to end so they can get back to normal. Trump himself has not made a case for a serious nationalist program. This is because he is not a servant of nationalism; nationalism is his tool, if not simply a brand name, which he deploys to justify his whims and legitimate his will. Likewise, outside the ranks of a few intellectuals, his most ardent supporters have no allegiance to an actual nationalist program. They have allegiance to Trump. If nationalism were a serious national program, they would condemn some of his actions, such as offering the American military to be mercenaries for Saudi Arabia. But nationalism is an afterthought among the base, if it is a thought at all.

Another lesson: Labels are funny things. This is a point that cuts somewhat in the new nationalists’ favor. While it would be better if they grappled more with the lessons of history and how this idea was applied in the past, today’s nationalists are under no obligation to own prior meanings as their own. Moreover, labels take on new meanings as new events make their impression on them. Obviously, it’s no surprise that the nationalism of Mussolini and Hitler didn’t factor into the nationalism of Bellamy—because it hadn’t happened yet. But it’s also worth noting that the nationalism of Fichte and Herder—the German architects of Enlightenment-era nationalism—were missing from the discussion of Bellamy’s nationalism, as well. In other words, as a political brand, the American nationalism of the 19th and early 20th century was largely disconnected from the connotations of European nationalism of the 18th century—where it was born. The original nationalism that led to the creation of Germany was thoroughly romantic, drawing its strength from rebellion against the French Enlightenment and the suppression of the German language, German culture and the myths of the Germanic past. Bellamy’s nationalism, despite the title of his book, was entirely forward-looking and hopeful to the point of being literally utopian.

Similarly, when Donald Trump calls himself a nationalist—whatever he means by that—there is no connective tissue to the nationalism of Bellamy or even either of the Roosevelts, in much the same way his use of once-odious terms like “America First” can be defended on the grounds that President Trump was wholly ignorant of the term’s history and connotations.

But what of the conservative nationalists who cannot hide behind that excuse? Surely the story of Bellamy’s nationalism warrants a paragraph or a footnote? Why the airbrushing?

Conservatism and nationalism.

I think part of the answer stems from the fact that the conservative nationalism being constructed today is not all that dissimilar from Bellamy’s project. No, it is not socialist—though sometimes it is somewhat utopian, more than a little populist, and far more sympathetic to state-run planning than I would like. No, the real similarity lay in the fact that both were, in a sense, made up to put an intellectual veneer around a political program. Read the canonical books of post-World War II intellectual conservatism. You’ll struggle to piece together a few pages worth of serious discussion of nationalism. This isn’t to say you won’t find a great deal on the plight of the nation, the need for some kind of national consensus, or the importance of patriotism (which as I argue below is not synonymous with nationalism as some nationalists contend). But nationalism as a stand-alone concept, never mind the cure for what ails us, was never a major part of the conservative conversation.

This is not, however, the case with the Irish statesman Edmund Burke, widely seen as the father of Anglo-American conservatism. He was very concerned with the concept of the nation, but his “nationalism” was not a centralizing idea. He saw the nation as a rich ecosystem or garden of liberty, in which different subnational communities and ethnicities—specifically the Irish, the Scotsm et al — had space to live according to their own customs concurrently with their national, British, identity. This is an older conservative understanding of the nation, that has analogs in the American conservative’s case for federalism. As St. Stephen, the King of Hungary said, “Remember that a country of only one language and one custom is a fragile and silly thing.”

The modern conservative aversion to nationalism was in part a response to the legacy of people like Bellamy—as well as the intellectuals and politicians he influenced such as Herbert Croly, John Dewey, and the Roosevelts. American nationalists, historically, believe in nationalization. FDR was a nationalist in this sense. He may have also been a patriot, but his definition of patriotism saw no conflict with the state commandeering vast swaths of the economy. Indeed, it’s no wonder Bellamyites saw so much of themselves in the New Deal. For instance, the New Deal—which FDR explicitly sold as a continuation of Woodrow Wilson’s “war socialism” for domestic purposes—embraced industrial armies under the National Recovery Administration and its seal the Blue Eagle. In 1933, New York City shut down for the “President’s NRA-Day Parade”—the largest parade the city had ever seen until then. Laborers marched in accord to their profession: 50,000 garment workers, 30,000 city laborers, 17,000 retail workers, 6,00- brewery hands, and a Radio City Music Hall troupe. Nearly 250,000 men and women marched for 10 hours past an audience of more than 1 million people as 49 military planes flew overhead. Whatever you think about that, it was certainly a nationalist spectacle.

Again, FDR did not hide the fact national militaristic solidarity was his guiding principle of the New Deal and the battle against the Depression. As he proclaimed when he signed the National Recovery Act:

“It is the most important attempt of this kind in history. As in the great crisis of the [first] World War, it puts a whole people to the simple but vital test: ‘Must we go on in many groping, disorganized, separate units to defeat or shall we move as one great team to victory?’”

This all made perfect sense given the internal logic of American nationalism from Bellamy to FDR. Today’s national conservatives place enormous patriotic and political importance on the U.S. military. I have no quarrel with much of this, but it is worth noting that for more than a century, progressives have seen military mobilization as a defining concept for their domestic agendas. Bellamy was a pacifist, but he recognized war and mobilization as a profoundly virtuous source of social solidarity. (Though I should note: Later in life when his militarism proved inconvenient for broadening the movement, he embraced bureaucracy and the civil service as a more palatable means of regimenting society.) This was William James’ argument in his “Moral Equivalent of War” lecture, which became a defining leitmotif of progressivism for generations, particularly under the New Deal, but also JFK’s “New Frontier” and the Green New Deal today.

Much of the American left, at least prior to the 1960s, was thoroughly nationalist, not in the Trumpian—never mind Hitlerite—sense (though Woodrow Wilson’s nationalism exceeded the former and came disgustingly close to the latter), but in the way that Bellamy, Dewey, and FDR were. In no way was this always a bad thing, but progressive nationalism—and the nationalization that came with it—was indeed a thing. As the labor historian Nelson Liechtenstein writes, “All of America’s great reform movements, from the crusade against slavery to the labor upsurge in the l930’s, defined themselves as champions of a moral and patriotic nationalism, which they counterposed to the parochial and selfish elites which stood athwart their vision of a virtuous society.” Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of today’s ideological combat is the effort by both the right and left to airbrush this fact from historical memory.

Sen. Bernie Sanders is constantly hailed for his enduring consistency, with young self-described socialists touting YouTube videos of a young Sanders saying the same things he says today. They leave out that Sanders once considered “open borders” to be a right-wing scheme to devalue American labor. “No, that’s a Koch brothers proposal,” he said. “I think from a moral responsibility, we’ve got to work with the rest of the industrialized world to address the problems of international poverty,” he added, “but you don’t do that by making people in this country even poorer.” That’s nationalism. One might even say that’s America First.

Regardless, modern conservatism was born as a full-throated rejection of the spirit of nationalization and to some extent a rediscovery of Burkeanism. Russel Kirk, author of the foundational The Conservative Mind, despised conscription as a form of slavery (“there is no tyranny more onerous than military life.”). He feared that the nationalist temper of the New Deal and World War II would be extended into peacetime. “Abstract humanitarianism has come to regard servitude—so long as it be to the state—as a privilege.” It is hard to understand how a movement in which the Southern Agrarians—for good and ill—played such an outsized role can suddenly be a champion of nationalism.”

Many national conservatives fairly object that they like nationalism, but remain as skeptical as ever about nationalization. I believe most of them. But there’s a philosophical disconnect between celebrating nationalism, national unity, and the glories of nationhood and opposing nationalization: The latter logically flows from the former. There is only one entity that fairly claims to speak for the whole nation: the federal government. Even that is not quite right, because members of the legislative branch are not elected to represent the nation but their constituents. Only the president, we are constantly told, is elected by the entirety of the nation. I can find nothing in American conservatism that can sustain the notion that one person deserves the sort of deference that nationalism taken to its logical conclusions bestows upon the president.

But even if we consider the lesser proposition that the government in Washington is the voice of the whole corpus mysticum that is the Nation, we are still left granting it more deference than it deserves. If the nation is the highest good, then the rights and independence of local communities, civil society, and the smallest minority, the individual, must be secondary considerations. Of course, there are times when this is actually true—most obviously during wartime, which is precisely why statists have always tried to marshal a crisis atmosphere in order to activate the wartime powers of the state. But in a properly functioning democracy, these times are supposed to be rare and widely accepted. In all other times, disagreement and autonomy are supposed to be the order of the day.

Because there is no limiting principle to nationalism, when we elevate the nation above all other considerations we nationalize politics and make speaking for the nation-as-a-whole the goal of all political contests. And because in a sprawling continental democracy no agenda will speak for the whole of the nation, we turn elections into a license for unchecked power. A president Bernie Sanders would have every bit as much right to speak for the whole of the nation as president Trump claims to.

There is a robust argument about whether nationalism and patriotism are synonyms. There are good lexicological and etymological arguments on both sides. But if these two words mean the same thing, then we need another word to do the job a certain kind of patriotism does and nationalism does not. If George Washington had decided to become president for life, there’s nothing in nationalism that could condemn him for it. But the kind of patriotism I have in mind would judge him harshly.

Lord Acton recognized the difference between mere “nationality” and patriotism. “Our connection with the race is merely natural or physical, whilst our duties to the political nation are ethical,” Acton wrote. “One is a community of affections and instincts infinitely important and powerful in savage life, but pertaining more to the animal than to the civilised man; the other is an authority governing by laws, imposing obligations, and giving a moral sanction and character to the natural relations of society.”

For Acton, the patriot is loyal to a cause as much to the nation, because the two are not the same thing. Patriotism is that ethical spirit which allows some to stand athwart the will of a nation—or a mob—in a given moment and yell, “Stop.” Patriotism can draw on the nationalist spirit when necessary (as Lincoln brilliantly did in his “Electric Cord” speech), in the same way we can yoke our passions to fighting for a just cause, but our passions alone do not render our causes just and nationalism alone does not make a cause patriotic. So, yes, of course, sometimes the nation’s will is indistinguishable from the patriot’s verdict, and many nationalists are also patriots. But when blood is pounding in the nationalist’s ears for an unjust cause, it is the patriot who courageously reminds them that fervor is no replacement for an argument, that one with the law on his side is a majority, and that while this nation may still be the last best hope on Earth, it is not always right.

Footnote: Among the books I have in mind are: Return of the Strong Gods: Nationalism, Populism, and the Future of the West by R. R. Reno; Age of Iron: On Conservative Nationalism by Colin Dueck; The Nationalist Revival: Trade, Immigration, and the Revolt Against Globalization by John B. Judis; The Case for Nationalism: How It Made Us Powerful, United, and Free by Rich Lowry; The Virtue of Nationalism by Yoram Hazony; Why Nationalism by Yael Tamir; Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism by Benedict Anderson; The MAGA Doctrine: The Only Ideas That Will Win the Future by Charlie Kirk; Us vs. Them: The Failure of Globalism by Ian Bremmer.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.