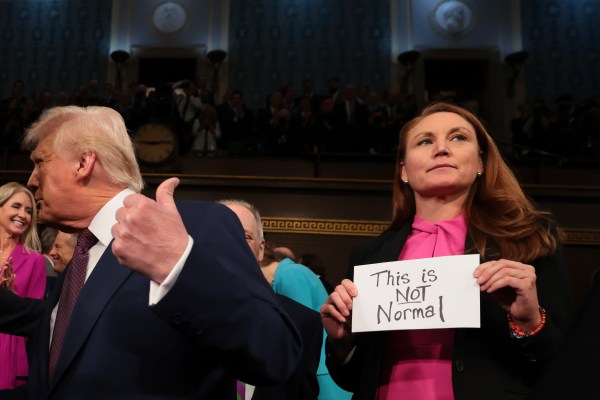

Donald Trump and Elon Musk’s DOGE team continues to slash federal government spending in an almost bafflingly cruel, capricious, and haphazard way. To call the cuts “selective” would be a wild understatement. Apparently, the federal government can afford to spend $1 trillion on defense, but it cannot afford to help public schools whose students might be getting lead poisoning, or to fund PEPFAR, a wildly successful program to fight HIV and AIDS worldwide that has enjoyed bipartisan support since President George W. Bush first championed and launched it.

While it’s important not to dismiss the profound harm Trump’s budget-cutting rampage is causing, the rampage raises the question of what exactly Trump’s detractors, were they in power, would do instead. For years now, liberals have failed to make a clear, assertive case for what government should do. This can partly explain why the burn-it-all-down MAGA movement has had so much success, with Trump, remarkably, viewed as more trustworthy than Kamala Harris on a variety of policy issues right before the election.

Part of the problem is that there has been a failure of introspection on the left—a failure to understand why so many Democrat-run states and cities have become how-not-to case studies. One major culprit here is our bottomless belief in funding as the end-all, be-all of policy, with far less attention paid to how public dollars are spent. “Fund XYZ!” goes the mantra, with XYZ being anything from education to health care to fighting homelessness. But the world is a lot more complicated than that.

One example of this type of complexity is the tragic case of Jordan Neely. On May 1, 2023, Neely, a homeless man, became agitated on a New York City subway car. He shouted that he was “fed up and hungry,” “tired of having nothing,” that “someone is going to die today,” and that he was prepared to go to jail. A then 24-year-old former Marine named Daniel Penny put Neely in a protracted chokehold. Tragically, Neely died as a result.

The response from many progressives was immediate: Clearly, this showed that New York City’s social services were underfunded. How else could someone like Neely have fallen through the cracks in America’s biggest, richest city? (Penny was acquitted of criminally negligent homicide late last year.)

In decrying Neely’s death and the acquittal of the man who killed him, multiple city council members cited a lack of resources for individuals facing homelessness and/or mental health crises as the obvious problem. After Neely’s death, the National Alliance to End Homelessness demanded that “federal, state, and local leaders to adequately fund interim solutions and invest in affordable housing and behavioral health services to address the needs of families, youth, and individuals experiencing homelessness.”

But subsequent reporting didn’t really prove that more funding would mean Neely would still be alive. Rather, the most straightforward answer was simply that the City of New York did have an opportunity to help Neely—many opportunities—but instead it let him walk free, again and again, despite him clearly being a threat to both himself and others. Neely was well-known to the city’s social services and was, in fact, on a list of the most at-risk homeless people in the five boroughs, with outreach workers regularly checking in on him. Most recently, at the time of his death, he had simply walked out of a treatment facility to which he had been sentenced in lieu of prison, just his latest pass through New York City’s revolving-door approach to dealing with severely disturbed individuals, which generally does not force people into treatment. In the worst cases, assaults and murders have been allegedly perpetrated by mentally ill individuals with long and violent criminal histories, raising the obvious question of why they were not behind bars.

As Freddie deBoer, a lefty writer who has been frank about his own at-times severe mental health struggles, wrote last year: “I’ve asked again and again and again: what do you do, as was the case with people like Jordan Neely … when someone who lives on the streets has access to housing and mental health treatment but refuses it? What do you do when someone is clearly going to die but is incapable of accepting help? No one can give me an answer.”

That’s part of the reason for knee-jerk demands for funding: to avoid giving an answer to an uncomfortable question. “Fund XYZ” allows us to float high above the complex human messiness of deciding whether the state should be allowed to involuntarily confine a schizophrenic young man and possibly force him to take medication. If the problem is always that XYZ isn’t funded enough, we don’t really have to dive deep into our questions of values or potentially uncomfortable tradeoffs.

Another, broader example is the outsourcing of city services to nonprofits. Here, San Francisco stands out. As The San Francisco Standard has reported, the city funneled tens of millions of dollars to “revoked, suspended, [and] delinquent nonprofits” dedicated to “some of the city’s biggest crises: homelessness, drug addiction, assisting disadvantaged schoolchildren and offering subsidized health care to low-income residents and communities of color.” The lack of oversight defies belief; in one case, the Standard reported, a homelessness organization that had received tens of millions of city and federal funding had its nonprofit status revoked by the state attorney general’s office after it “failed to respond to multiple requests for financial documentation and filing fees going back to 2017.” But the city of San Francisco simply didn’t notice, and continued working with the organization for months after this occurred, despite the fact that charities cannot operate in California if they lack nonprofit certification. City officials only realized that the group had lost its status when The Standard reached out to them.

San Francisco, in short, has not spent its social services money wisely, and has not done a good job tracking the efficacy of the numerous nonprofits to which it outsources key services. Despite this, in January, then-Mayor London Breed and Supervisor Rafael Mandelman announced the results of a report calling for more funding to “expand residential treatment” for those with complex mental health needs. This may well be a worthy cause, but how is the average taxpayer supposed to know this money will be spent responsibly? And what about the fact that California state law has long hampered local officials’ ability to coerce even extremely unwell people into treatment? (In theory, a law signed by Gavin Newsom in late 2023 makes it easier to do so, but it remains to be seen whether that will improve the homelessness problem in places like San Francisco.) But again, simply calling for more funding is easier than taking a hard look at whether the noble-seeming groups getting that funding are pulling their weight and delivering on their promises and contracts—or debating whether and under what circumstances the state should take a more coercive approach to homeless people who are in no condition to care for themselves.

In short, no one who is informed about the underlying issue thinks that San Francisco’s problem is that it doesn’t spend enough money on these problems. Rather, the money isn’t wisely spent. And every story like this only further fuels the populist rage that propelled Trump into office a second time.

Luckily, there’s a faction of liberals who have begun speaking much more forthrightly about Democrats’ tendency toward self-inflicted dysfunction—about the problem of “Funding XYZ” without doing so in an intelligent manner.

The best recent example is Abundance, a book by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson that came out last month. “What matters is not what gets spent,” they argue early on, pushing back against the idea that more funding is always inherently better. “What matters is what gets built.” You can replace “what gets built” with “who gets treatment” or “who gets broadband internet” and the same logic will apply: What matters is not the funding of a project, but that project’s result.

Klein and Thompson’s stories of government waste, particularly in (you guessed it) California, are gobsmacking. Perhaps most famous is the high-speed rail system that was supposed to whisk passengers between San Francisco and Los Angeles. Authorized by voters in 2008, a year later it was considered a “signature project” of then recently elected President Barack Obama, and state officials claimed that the route would be complete by 2020. Now, almost two decades later, it is tens of billions of dollars over budget and almost entirely unbuilt, undone by what Klein and Thompson view as an unduly litigious, complex regulatory landscape. “What has taken so long on high-speed rail is not hammering nails or pouring concrete,” they write. “It's negotiating. Negotiation with courts, with funders, with business owners, with homeowners, with farm owners.”

Or take Proposition HHH, in which Los Angeles voters raised taxes to generate $1.2 billion in funding to build 10,000 units of housing for the homeless. Eight years later, less than half that number had been built, and the average cost of those units was a calamitous almost $600,000 each. “The cost of building many of these units exceeds the median sale price of a market-rate condominium in the City of Los Angeles and a single-family home in Los Angeles County,” noted a subsequent audit.

In addition to wasting countless taxpayer dollars, these sorts of projects turn liberal state-capacity ideals into a punching bag for the right. To take one final, particularly painful example, Klein and Thompson note that former President Joe Biden’s “infrastructure bill … included $7.5 billion to build a national network of 500,000 electric vehicle charging stations; by March 2024—more than two years after the bill passed—only seven new chargers were up and running.” It almost makes you want to vote to burn it all down.

Now, I am admittedly putting a bunch of apples and oranges into the same basket here. No two instances of wasteful spending are alike, and the causes can range from overly restrictive regulations (a prime target of Klein and Thompson) to what are effectively patronage systems, in places like San Francisco, that transfer public funds to politically favored and connected nonprofits. But what all these cases have in common is that truly examining them requires difficult, politically fractious conversations. These conversations can be evaded, rather conveniently, by simply screaming, for the millionth time, that America doesn’t pour enough money into social services. In many cases where liberals have broad power to tax and spend, unfortunately, the jig is up.

When the average citizen sees money that is earmarked for important social causes get wasted or deployed with comical inefficiency, it (naturally) reduces their trust in government’s ability to take on these tasks at all; it gives them less reason to take governance itself seriously.

But again, there is an opportunity lurking on the horizon. Americans are about to find out what happens when the most powerful people in government are themselves hostile to government services, and the results are not going to be pretty. So when the pendulum inevitably swings back, will liberals be prepared with a more reality-based, compelling message than “Fund XYZ!”? They had better be, because another Trump will likely be waiting in the wings.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.